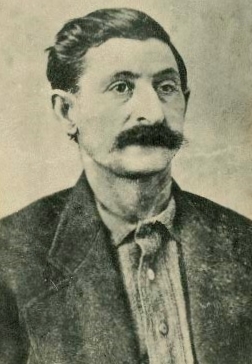

Big Nose George - from Wikipedia

| George Parrott, also known as Big Nose George, Big beak

Parrott, George Manuse and George Warden, was a cattle rustler and highwayman

in the American Wild West in the late 19th century. His skin was made into

a pair of shoes after his lynching and part of his skull was used as an

ashtray.

Outlaw

In 1878, Parrott and his gang murdered two law enforcement

officers — Wyoming deputy sheriff Robert Widdowfield and Union Pacific

detective Tip Vincent — after a bungled train robbery. Widdowfield and

Vincent were ordered to track down Parrott's gang on August 19, 1878, following

the attempted robbery on an isolated stretch of track near the Medicine

Bow River The officers traced the outlaws to a camp at Rattlesnake Canyon,

near Elk Mountain, where they were spotted by a gang lookout. The robbers

stamped out the campfire and hid in a bush. When Widdowfield arrived at

the scene, he realized the ashes of the fire were still hot. The gang ambushed

the two lawmen, shooting Widdowfield in the face. Vincent tried to escape,

but was shot before he made it out of the canyon. The gang took each mans'

weapons and one of their horses before covering up the bodies and fleeing

the area.

The murder of the two lawmen was quickly discovered and

a $10,000 reward was offered for the "apprehension of their murderers".

This was later doubled to $20,000. |

George Parrott |

In February 1879, "Big Nose" George and his cohorts were

in Milestown (now Miles City, Montana). It was known around Milestown that

a prosperous local merchant, Morris Cahn, would be taking money back east

to buy stocks of merchandise. George, Charlie Burris and two others carried

out a daring daylight robbery despite Morris Cahn traveling with a military

convoy containing 15 soldiers, two officers, an ambulance, and a wagon

from Fort Keogh, which was tasked to collect the army payroll. At a site

approximately 10 miles beyond the Powder River Crossing, near present-day

Terry, Montana, there is a steep coulee (known ever since as "Cahn's Coulee").

Approaching the coulee over a five-mile plateau, the soldiers, ambulance

and the wagon became "strung out", creating large gaps between party members.

The gang donned masks and stationed themselves at the bottom of the coulee,

at a turn in the trail. The gang first surprised and then captured the

lead element of soldiers, as well as the ambulance with Cahn and the officers.

They waited and likewise captured the rear element of soldiers with the

wagon. Cahn was robbed of an amount between $3,600 and $14,000, depending

on who was doing the reporting.

Arrest

In 1880 following the robbery of Cahn, Big Nose George

Parrott and his second, Charlie Burris or "Dutch Charley", were arrested

in Miles City by two local deputies, Lem Wilson and Fred Schmalsle. Big

Nose and Charlie got drunk and boasted of killing the two Wyoming lawmen,

thus identifying themselves as men with a price on their head. Parrott

was returned to Wyoming to face charges of murder.

Lynching

Parrott was sentenced to hang on April 2, 1881, following

a trial, but tried to escape while being held at a Rawlins, Wyoming jail.

Parrott was able to wedge and file the rivets of the heavy shackles on

his ankles, using a pocket knife and a piece of sandstone. On March 22,

having removed his shackles, he hid in the washroom until jailor Robert

Rankin entered the area. Using the shackles, Parrott struck Rankin over

the head, fracturing his skull. Rankin managed to fight back, calling out

to his wife, Rosa, for help at the same time. Grabbing a pistol, she managed

to persuade Parrott to return to his cell.

News of the escape attempt spread through Rawlins and

groups of people started making their way to the jail. While Rankin lay

recovering, masked men with pistols burst into the jail. Holding Rankin

at gunpoint, they took his keys, then dragged Parrott from his cell.

Parrott's "rescuers" turned out to be townspeople, bringing

Parrott out to a lynch mob of more than 200 people. The mob strung him

up from a telegraph pole.

Charlie Burris suffered a similar lynching not long after

his capture having been transported by train to Rawlins, a group of locals

found him hiding in a baggage compartment and proceeded to hang him on

the crossbeam of another nearby telegraph pole.

Desecration of remains

Doctors Thomas Maghee and John Eugene Osborne took possession

of Parrott's body after his death, to study the outlaw's brain for clues

to his criminality. The top of Parrott's skull was crudely sawn off, and

the cap was presented to 15-year-old Lillian Heath, then a medical assistant

to Maghee. Heath became the first female doctor in Wyoming and is said

to have used the cap as an ash tray, a pen holder and a doorstop. A death

mask was also created of Parrott's face, and skin from his thighs and chest

was removed. The skin, including the dead man's nipples, was sent to a

tannery in Denver, where it was made into a pair of shoes and a medical

bag. They were kept by Osborne, who wore the shoes to his inaugural ball

after being elected as the first Democratic Governor of the State of Wyoming.

Parrott's dismembered body was stored in a whiskey barrel filled with a

salt solution for about a year, while the experiments continued, until

he was buried in the yard behind Maghee's office.

Rediscovery

The death of Big Nose George faded into history over the

years until May 11, 1950, when construction workers unearthed a whiskey

barrel filled with bones while working on the Rawlins National Bank on

Cedar Street in Rawlins. Inside the barrel was a skull with the top sawed

off, a bottle of vegetable compound, and the shoes said to have been made

from Parrott's thigh flesh. Dr. Lillian Heath, then in her eighties, was

contacted and her skull cap was sent to the scene. It was found to fit

the skull in the barrel perfectly, and DNA testing later confirmed the

remains were those of Big Nose George. Today the shoes made from the skin

of Big Nose George are on permanent display at the Carbon County Museum

in Rawlins, together with the bottom part of the outlaw's skull and Big

Nose George's earless death mask. The shackles used during the hanging

of the outlaw, as well as the skull cap, are on show at the Union Pacific

Museum in Omaha, Nebraska. The medicine bag made from his skin has never

been found.

Legends

Many legends surround Big Nose George—including one which

claims him as a member of Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch. Cassidy, however,

would only have been 14 at the time of George's death, so this theory has

been ruled out by historians. There is also speculation that he ran with

the James brothers—with the flames of this rumor fanned by George himself.

During a pre-trial interview in 1880, Big Nose stated that his outlaw pal

Frank McKinney had claimed to be Frank James. He also told investigators

that another member, Sim Jan, was the gang leader—leading to wild rumors

that Frank and Sim were the infamous James brothers, Frank and Jesse.

However, it is generally agreed that Parrott was more

of a run-of-the-mill horse thief and highwayman. His gang enjoyed a successful

run of robbing pay wagons and stagecoaches of cash in the late 1870s, but

a yearning for bigger profits led to the attempted train robbery.

|

Valery Havard - from Wikipedia

| Valery Havard (February 18, 1846 – November 6, 1927),

was a career army officer, physician, author, and botanist. Although he

held many notable posts during his military career, he is most well known

for his service on the western frontier of the United States and in Cuba.

Many Texas plants are named for Havard, including the Chisos bluebonnet

(Lupinus havardii), Havard oak (Quercus havardii), and Havard's evening

primrose (Oenothera havardii).

Biography

Early life

Havard was born in Compiegne, France. After graduating

from the Institute of Beauvais, he studied medicine in Paris before immigrating

to the United States. He entered Manhattan College and the medical department

of New York University, in New York City, graduating from both in 1869.

For a time thereafter he was house physician in Children's Hospital and

professor of French, chemistry, and botany at Manhattan College.

Frontier posts

In 1871, he was appointed an acting assistant surgeon

in the army and was commissioned an assistant surgeon in |

Valery Harvard |

the medical corps three years later. For six months in 1877,

he served with the 7th Cavalry in Montana in pursuit of hostile Sioux and

Nez Perce Indians. In 1880, he joined the 1st Infantry then engaged in

opening roads in the Pecos River Valley in west Texas. In the summer of

1881, he accompanied an exploring expedition into northwest Texas, headed

by Captain William R. Livermore, Corps of Engineers. From stations at Fort

Duncan and San Antonio, he again went with exploring parties under Captain

Livermore to the upper Rio Grande valley during the summers of 1883 and

1884. While on frontier duty he became interested in economic botany and

studied the food and drink plants of the Indians, Mexicans, and early settlers.

Havard served in various posts from 1884 to 1898, including

service in New York (Fort Schuyler, Fort Wadsworth, and the recruiting

depot at Davids' Island), North Dakota (Fort Lincoln and Fort Buford),

and Wyoming (Fort D. A. Russell).

Spanish–American War

With the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in 1898,

Havard was assigned as chief surgeon of the Cavalry Division, and accompanied

the Division to Siboney, Cuba. He served in the field during the Battle

of San Juan Hill on July 1. After the war, he joined the staff of General

Leonard Wood in Havana as chief surgeon of the Division of Cuba and continued

with Wood when he became military governor. While in Havana in October

1900, he was the subject of a severe attack of yellow fever.

Russo-Japanese War

With the establishment of civil government in Cuba, Colonel

Havard returned to the United States for duty in Virginia (Fort Monroe)

and New York (West Point and Department of the East at Governors Island).

In 1904, he was detailed as medical attaché with the Imperial Russian

Army during the Russo-Japanese War. Havard arrived in St. Petersburg on

December 7, 1904 and reached the frontlines in Manchuria on February 8,

1905. After being embedded with Russian forces just over a month, Havard

was captured by the Imperial Japanese Army at the Battle of Mukden. Upon

reaching Tokyo he was sent back to the United States.

In his official report, Havard compiled a list of lessons

learned from the Russo-Japanese experience. He noted the lack of frontal

assaults that were the result of improved weaponry, particularly the machine

gun. Flanking movements became more necessary to avoid the machine gun,

which necessitated increased frequency and distance of forced marches.

In previous wars, soldiers were able to rest at night and armies saw little

action during winter months. Both practices had become antiquated. Attacks

were often ordered at night and the waging of war never ceased, even in

sub-zero temperatures. According to Havard, the result of these trends

was soldiers experiencing an increased amount of battle fatigue, as well

as resurgence in the usefulness of the bayonet in night assaults. The Japanese

claimed seven percent of their casualties resulted from bayonet wounds.

Because of his observations in Manchuria, Havard recommended

changes to the U.S. Army’s Medical Corps. He suggested the war department

devise a plan to train and mobilize large numbers of medical personnel

for war and to promote the development of civilian organizations like the

Red Cross. Because of the increased number of casualties resulting from

modern weaponry, Havard stressed the significance of training enlisted

soldiers in assisting medical officers in field hospitals. He also spoke

to the importance of devising an adequate evacuation system from the battlefield

to military hospitals. He explained that railroads were of importance in

this process. Havard also advocated the implementation of telephone technology

in order for hospital staff to have quick access to information from the

battle.

He was subsequently elected to a term as president of

the Association of Military Surgeons. In 1906 he was appointed president

of the faculty of the Army Medical School, which he held until he retired

from military duty in 1910. Upon retirement Havard established his home

in Fairfield, Connecticut. There he continued a career of writing begun

when he entered the army.

World War I

With the onset of World War I, Colonel Havard was called

from retirement for duty with the Cuban government in the reorganization

of the medical departments of its army and navy (1917–1923), for which

he received the Cuban Order of Military Merit. In his eighty-first year,

he died on board the steamship Columbo while returning from a visit to

France.

Writings

Havard's early articles were on botany and military hygiene,

continued with reports on observations on the Spanish-American and Russo-Japanese

Wars. While at Fort Lincoln in 1889, Havard published a "Manual of Drill

for the Hospital Corps". He won the Enno Sander prize given by the Association

of Military Surgeons in 1901 with an essay on "The Most Practicable Organization

for the Medical Department of the United States Army in Active Service".

Pamphlets on "Transmission of Yellow Fever" (1902) and "The Venereal Peril"

(1903) were issued as government publications. During his last service

in Washington, he published his "Manual of Military Hygiene" (1909), with

second and third editions (1914 and 1917) prepared at Fairfield. At time

of publication this was the best work on military hygiene yet produced

in this country.

Havard's article "The French Half-breeds of the Northwest"

was published in the Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution (1879).

He published a number of articles on the flora of Montana, North Dakota,

Texas, and Colorado, including "Botanical Outlines" in Report of the Chief

of Engineers, Part III (1878), and "Report on the Flora of Western and

Southern Texas" in Proceedings of the United States National Museum (1885).

Havard's "Notes on Trees of Cuba" was published in The Plant World, IV

(1901).

The standard author abbreviation Havard is used to indicate

this person as the author when citing a botanical name.

|

| Hugh Anderson - from Wikipedia

Hugh Anderson (1851–1873 or 1914?) was a cowboy and gunfighter

who participated in the infamous Gunfight at Hide Park on August 19, 1871,

in Newton, Kansas. Prior to the gunfight, Anderson was a son of a wealthy

Bell County, Texas cattle rancher who drove from Salado, Texas to Newton.

Anderson was the one who led the cowboy faction during the gunfight, and

was also one of the first to draw blood.

The incident began with an argument between two local

lawmen, Billy Bailey and Mike McCluskie. The two men began arguing on August

11, 1871, over local politics on election day in the "Red Front Saloon",

located in downtown Newton. The argument developed into a fist fight, with

Bailey being knocked outside the saloon and into the street. McCluskie

followed, drawing his pistol. He fired two shots at Bailey, hitting him

with the second shot in the chest. Bailey died the next day, on August

12, 1871. McCluskie fled town to avoid arrest, but was only away for a

few days before returning, after receiving information that the shooting

would most likely be deemed self defense, despite the fact that Bailey

never produced a weapon. McCluskie had claimed he feared for his life,

having known that in three previous gunfights, Bailey had killed two men.

The murder of Mike McCluskie and the gunfight

Hugh Anderson led the Texans in vowing revenge for Bailey's

death. On August 19, 1871, McCluskie entered Newton and went to gamble

at "Tuttles Dance Hall", located in an area of town called Hide Park. He

was accompanied by a friend, Jim Martin. As McCluskie settled into gambling,

three cowboys entered the saloon. They were Billy Garrett, Henry Kearnes,

and Jim Wilkerson, all friends to Bailey. Anderson arrived soon after.

Anderson confronted McCluskie and the two had a bitter

exchange of words, before Anderson ended up shooting McCluskie in the neck

and body. The latter tried to shoot back at Anderson, hitting him in the

neck, but Anderson continued firing. After McCluskie's gun finally misfired,

Anderson walked over him and shot him in the back several times. At that

point James Riley, believed to have been 18 years of age at the time, opened

fire on them. Riley was dying from tuberculosis, and had been taken in

by McCluskie shortly after arriving in Newton. Riley had never been involved

in a gunfight before, but only Anderson still had a loaded pistol to return

fire. Some accounts say Riley locked the saloon doors before shooting,

but this seems unlikely. The room was filled with smoke from all the prior

gunfire, and visibility was bad. Riley ended up hitting seven men. More

casualties soon followed between the patrons of the saloon.

Mike McCluskie died in the following morning, and an arrest

warrant was issued for the wounded Hugh Anderson. But his friends managed

to spirit him away back to Kansas City first then to Texas before the local

law could get him.

Duel with Arthur McCluskie

Anderson recovered from his wounds and by 1873 had become

a bartender in Medicine Log, Kansas. Unknown to Anderson, the brother of

Mike McCluskie, Arthur McCluskie, had been searching for him to avenge

his brother, located him and challenged him to a duel. Anderson accepted

the duel and was allowed to choose between pistols and knives; he chose

pistols, and a formal duel was arranged. While it was different from the

"quick draw duels" that became iconic in the West, the Anderson-McCluskie

duel was also different from "traditional duels" because it depended more

on speed and reaction time.

In late afternoon the two lined up as bystanders watched

the confrontation. They stood with their backs to each other at twenty

paces. At the sound of a signal (the gunshot from a pistol) the two quickly

turned to each other and fired their weapons. Their initial shots missed

but soon after Anderson hit McCluskie in the mouth and neck while the latter

hit Anderson in the arm. More shots were fired and McCluskie managed to

hit Anderson in the stomach. However, the first one to fall was McCluskie,

after Anderson emptied his pistol into him. Unfortunately for Anderson,

McCluskie wounds were not fatal, and the two resumed their duel with knives.

The second round saw Anderson and McCluskie repeatedly stabbing each other,

and ultimately McCluskie fell for a second time, which ended the duel.

He was rushed to a boarding house but died a day later. It was said that

Anderson lived a short time longer before dying from his wounds as well.

The duel was recorded in an article in the New York World on July 22, 1873.

Although some records said that Anderson died after his

duel, there were also reports that he survived his ordeal and came back

to live with his family. Three years later, Hugh was said to have moved

with his young son and several other family members to McCullock, Texas,

and the 1880 Federal Census listed Hugh, 28, and son, Oscar, 7, living

with his parents and working as a “stock raiser” in McCullock County. In

1884, at age 32, Hugh married a second time, Mag Cooke and moved to Chaves

County, New Mexico Territory, continuing his as a stock man. The U.S. Census

for 1900 listed Hugh as a widower. In 1910, Hugh is listed as a stock man

and living with his married son, Oscar, and three grandsons. Hugh Anderson

was listed to have died on June 9, 1914 at the age of 62 while herding

cattle in Lincoln County, New Mexico and getting struck by lightning.

|

| Kitty Leroy - from Wikipedia

Kitty Leroy (1850 – December 6, 1877) was a gambler, saloon

owner, prostitute and trick shooter of the American Old West.

Leroy was born in Michigan and by the age of 10 she was

dancing professionally. By the time she was fourteen she was performing

in dance halls and saloons. She also had developed shooting skills that

few could match, including the ability to shoot apples off people's heads.

A good-looking young woman, she married for the first time by 15, but the

marriage was short-lived as she was promiscuous and difficult to tame.

She ventured west seeking a wilder lifestyle, settling for a time in Dallas,

Texas. By the age of 20, she had married a second time and was one of the

most popular dancing attractions in town. She soon gave up dancing to work

as a faro dealer and became known for dressing in men's clothing, and at

times like a gypsie. By this time, Leroy had developed into a skilled gambler.

She and her second husband headed to California, where

they hoped to open their own saloon. Somewhere along the line, she left

him for another man, marrying for a third time. However, this marriage

was extremely short-lived. According to an unconfirmed legend, the two

became involved in an argument, during which she attacked him. When he

refused to hit her because she was a woman, she changed into men's clothing

and challenged him again. When she drew her gun, he did not, and she shot

him. As he did not die right away, she called for a preacher and the two

were married. He died within a few days.

Leroy made her way to Deadwood, Dakota Territory, in 1876,

traveling up on the same wagon train as Calamity Jane and Wild Bill Hickok.[citation

needed] There, she worked as a prostitute in the brothel managed by Mollie

Johnson. She opened the Mint Gambling Saloon and married for a fourth time

to a German prospector. However, when his money ran out, they began to

argue often. She hit him over the head with a bottle one night and threw

him out, ending the relationship.

Her saloon was successful. In addition to the gambling

income, Leroy occasionally worked as a prostitute but mostly managed her

own girls. On June 11, 1877, Leroy married for the fifth and final time,

this time to prospector and gambler Samuel R. Curley. This marriage, as

her others, was volatile. Curley was alleged to have been extremely jealous

and Leroy did not help matters, as she had numerous affairs, one of which

was with her latest ex-husband. On the night of December 6, 1877, Curley

shot and killed Leroy in the Lone Star Saloon, then turned the gun on himself

and committed suicide. The pair were laid in state in front of the saloon

the next day, then buried together. The January 7, 1878 issue of the Black

Hills Daily Times of Deadwood, under "City and Vicinity", reported:

The estate of Kitty Curley upon appraisment,

amounted to $650. More than one-half of which is claimed by and allowed

to

Kitty Donally, and the expenses have

doubtless consumed the balance. P.H. Earley has been appointed trustee

or guardian for the child.

She is mentioned in the HBO series Deadwood, portrayed

as a beautiful murder victim.

|

.

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|