Sarah Emma Edmonds - from

Wikipedia

| Sarah Emma Edmonds (December 1841 – September 5, 1898),

was a Canadian-born woman who is known for serving as a man with the Union

Army during the American Civil War. A purported master of disguise, Edmonds

exploits were described in the bestselling Nurse, Soldier, and Spy. In

1992, she was inducted into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame.

Early life

Born in 1841 in New Brunswick, then a British colony,

Edmonds grew up with her sisters on their family's farm. Edmonds fled home

at age fifteen, however, to escape an early marriage. Aided by her mother,

who herself married young, Edmonds escaped the marriage and ultimately

adopted the guise of Franklin Thompson to travel easier. A male disguise

allowed Edmonds to eat, travel, and work independently. Crossing into the

United States of America, Edmonds worked for a successful Bible bookseller

and publisher in Hartford, Connecticut.

Civil War Service

Sarah Emma Edmonds interest in adventure was sparked by

a book she read in her youth by Maturin Murry Ballou called Fanny Campbell,

the Female Pirate Captain', telling the story of Fanny Campbell and her

adventures on a pirate ship during the American Revolution while dressed

as a woman Fanny remained

dressed as a man in order to pursue other adventures,

to which Edmonds attributes her desire to cross dress. |

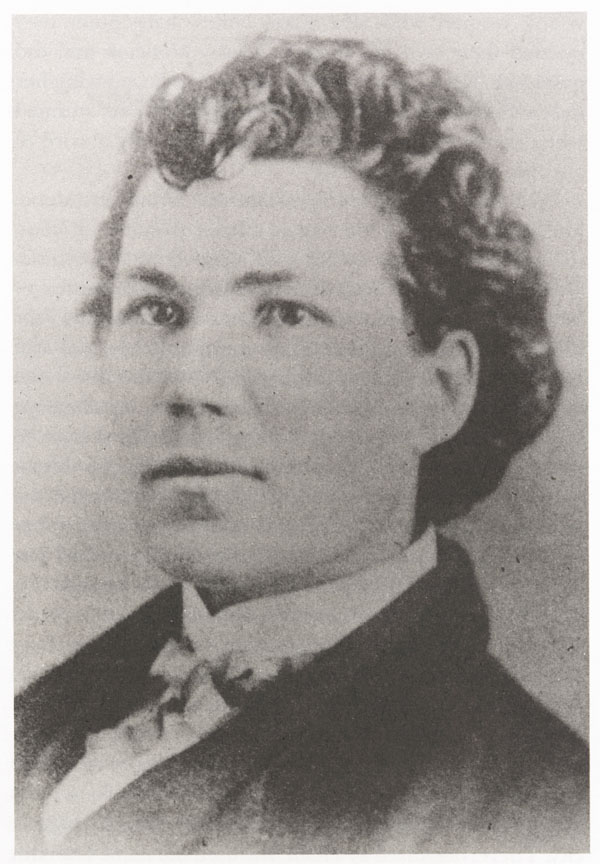

Sarah Edmonds

as Franklin Thompson |

During the Civil War, on May 25, 1861, she enlisted in Company

F of the 2nd Michigan Infantry, also known as the Flint Union Greys. On

her second try, she disguised herself as a man named "Franklin Flint Thompson,"

the middle name possibly after the city she volunteered in, Flint, Michigan.

She felt that it was her duty to serve her country and was truly patriotic

towards her new country. Extensive physical examinations were not required

for enlistment at the time, and she was not discovered. She at first served

as a male field nurse, participating in several campaigns under General

McClellan, including the First and Second Battle of Bull Run, Antietam,

the Peninsula Campaign, Vicksburg, Fredericksburg, and others. However,

some historians today say she could not have been at all these different

places at the same time.

Edmonds's career took a turn during the war when a Union

spy in Richmond, Virginia was discovered and went before a firing squad,

and a friend, James Vesey, was killed in an ambush. She took advantage

of the open spot and the opportunity to avenge her friend's death. She

applied for, and won, the position as Franklin Thompson. Although there

is no proof in her military records that she actually served as a spy,

she wrote extensively about her experiences disguised as a spy during the

war.

Traveling into enemy territory to gather information required

Emma to come up with many disguises. One disguise required Edmonds to use

silver nitrate to dye her skin black, wear a black wig, and walk into the

Confederacy disguised as a black man by the name of Cuff. Another time

she entered as an Irish peddler woman by the name of Bridget O'Shea, claiming

that she was selling apples and soap to the soldiers. Again, she was "working

for the Confederates" as a black laundress when a packet of official papers

fell out of an officer's jacket. When Thompson returned to the Union with

the papers, the generals were delighted. Another time, she worked as a

detective in Kentucky as Charles Mayberry, finding an agent for the Confederacy.

Edmonds's career as Frank Thompson came to an end when

she contracted malaria. She abandoned her duty in the military, fearing

that if she went to a military hospital she would be discovered. She checked

herself into a private hospital, intending to return to military life once

she had recuperated. Once she recovered, however, she saw posters listing

Frank Thompson as a deserter. Rather than return to the army under another

alias or as Frank Thompson, risking execution for desertion, she decided

to serve as a female nurse at a Washington, D.C. hospital for wounded soldiers

run by the United States Christian Commission. There was speculation that

Edmonds may have deserted because of John Reid having been discharged months

earlier. There is evidence in his diary that she had mentioned leaving

before she had contracted malaria. Her fellow soldiers spoke highly of

her military service, and even after her disguise was discovered, considered

her a good soldier. She was referred to as a fearless soldier and was active

in every battle her regiment faced.

Edmonds' Memoir

In 1864, Boston publisher DeWolfe, Fiske, & Co. published

Edmonds' account of her military experiences as The Female Spy of the Union

Army. One year later, her story was picked up by a Hartford, CT publisher

who issued it with a new title, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. It was

a huge success, selling in excess of 175,000 copies. Edmonds donated the

profits from her memoir to "various soldiers' aid organization."

Personal life

In 1867, she married Linnus. H. Seelye, a Canadian mechanic

and a childhood friend with whom she had three children. All three of their

children died in their youth, leading the couple to adopt two sons.

Later life

Edmonds became a lecturer after her story became public

in 1883. In 1886, she received a government pension of $12 a month for

her military service, and after some campaigning, was able to have the

charge of desertion dropped, and receive an honorable discharge. In 1897,

she became the only woman admitted to the Grand Army of the Republic, the

Civil War Union Army veterans' organization. Edmonds died in La Porte,

Texas, and is buried in the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) section of

Washington Cemetery in Houston. Edmonds was laid to rest a second time

in 1901 with full military honors.

Her publications

Edmonds, S. Emma E. Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: Comprising

the Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps, and Battle-Fields.

Hartford, Conn: W.S. Williams, 1865. OCLC 170538 Reprinted by Meadow Books

in 2006, ISBN 9781846850417

Legacy

A number of fictional accounts of her life having been

written for young adults in the 20th century, including Ann Rinaldi's Girl

in Blue. Rinaldi writes of Edmonds's life and how she became to be Franklin

Thompson.

She was inducted into the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame

in 1992.

|

Deborah Sampson - from Wikipedia

Deborah Sampson Gannett (December 17, 1760 – April 29,

1827), better known as Deborah Samson or Deborah Sampson, was a Massachusetts

woman who disguised herself as a man in order to serve in the Continental

Army during the American Revolutionary War. She is one of a small number

of women with a documented record of military combat experience in that

war. She served 17 months in the army under the name "Robert Shirtliff"

(also spelled in various sources as Shirtliffe and Shurtleff) of Uxbridge,

Massachusetts, was wounded in 1782, and was honorably discharged at West

Point, New York in 1783.

Early life

Deborah Sampson was born on December 17, 1760, in Plympton,

Massachusetts, into a family of modest means. Her father's name was Jonathan

Sampson (or Samson) and her mother's name was Deborah Bradford. Her siblings

were Jonathan (born 1753), Elisha (born 1755), Hannah (born 1756), Ephraim

(born 1759), Nehemiah (born 1764), and Sylvia (born 1766). Deborah's mother

was the great-granddaughter of William Bradford, Governor of Plymouth Colony.

Some of Deborah's ancestors included passengers on the Mayflower.

Deborah was told that her father had most likely disappeared

at sea, but evidence suggests that he actually abandoned the family and

migrated to Lincoln County, Maine. He took a common-law wife named Martha,

had two or more children with her, and returned to Plympton in 1794 to

attend to a property transaction. In 1770 someone called Jonathan Sampson

was indicted for murder in Maine; It is uncertain whether this individual

was Deborah's father because there are no existing records containing biographical

details about the defendant in the case.

|

Frontispiece of The Female Review:

Life of Deborah Sampson, the

Female Soldier in the

War of Revolution. |

When Deborah's father abandoned the family, her mother was

unable to provide for her children, so she placed them in the households

of friends and relatives, a common practice in 18th-century New England.

Deborah was placed in the home of a maternal relative. When her mother

died shortly afterwards, she was sent to live with Reverend Peter Thatcher's

widow Mary Prince Thatcher (1688-1771), who was then in her eighties. Historians

believe she learned to read while living with the widow Thatcher, who might

have wanted Deborah to read Bible verses to her.

Upon the widow's death, Deborah was sent to live with

the Jeremiah Thomas family in Middleborough, where she worked as an indentured

servant from 1770 to 1778. Although treated well, she was not sent to school

like the Thomas children because Thomas was not a believer in the education

of women. Sampson was able to overcome Thomas's opposition by learning

from Thomas's sons, who shared their school work with her. This method

was apparently successful; when her time as an indentured servant was over

at age 18, Deborah made a living by teaching school during the summer sessions

in 1779 and 1780. She worked as a weaver in the winter; Sampson was highly

skilled and worked for the Sproat Tavern as well as the Bourne, Morton,

and Leonard families. During her time teaching and weaving she boarded

with the families that employed her.

Sampson was also reported to have woodworking and mechanical

aptitude. Her skills included basket weaving, and light carpentry such

as producing milking stools and winter sleds. She was also experienced

with fashioning wooden tools and implements including weather vanes, spools

for thread, and quills for weaving. She also produced pie crimpers, which

she sold door to door.

Physical description

Sampson was approximately 5 feet 9 inches tall, compared

to the average woman of her day, who was around 5 feet, and the average

man, who was 5 feet 6 inches to 5 feet 8 inches tall. Her biographer, Hermann

Mann, who knew her personally for many years, implied that she was not

thin, writing in 1797 that "her waist might displease a coquette". He also

reported that her breasts were very small, and that she bound them with

a linen cloth to hide them during her years in uniform. Mann wrote that

"the features of her face are regular; but not what a physiognomist would

term the most beautiful".

A neighbor who as a boy knew Deborah as an elderly woman

remarked that she was "a person of plain features". A descendant named

Pauline Hildreth Monk Wise (1914–1994) was believed by relatives to have

strongly resembled Deborah, based on comparison of Pauline's physical appearance

to a 1797 portrait of Deborah, contemporary descriptions of Deborah's features

and height, and Pauline's height, which at 6 feet was taller than most

men. Sampson's appearance—tall, broad, strong, and not delicately feminine—contributed

to her success at pretending to be a man.

Army service

In early 1782, Sampson wore men's clothes and joined an

Army unit in Middleborough, Massachusetts, under the name Timothy Thayer.

She collected a bonus and then failed to meet up with her company as scheduled.

Inquiries by the company commander revealed that Sampson had been recognized

by a local resident at the time she signed her enlistment papers. Her deception

uncovered, she repaid the portion of the bonus that she had not spent,

but she was not subjected to further punishment by the Army. The Baptist

church to which she belonged learned of her actions and withdrew its fellowship,

meaning that its members refused to associate with her unless she apologized

and asked forgiveness.

In May 1782, Sampson enlisted again in Uxbridge, Massachusetts

under the name "Robert Shirtliff" (also spelled in some sources as "Shirtliffe"

or "Shurtleff", and joined the Light Infantry Company of the 4th Massachusetts

Regiment, under the command of Captain George Webb (1740–1825). This unit,

consisting of 50 to 60 men, was first quartered in Bellingham, Massachusetts,

and later mustered at Worcester with the rest of the regiment commanded

by Colonel William Shepard. Light Infantry Companies were elite troops,

specially picked because they were taller and stronger than average. Their

job was to provide rapid flank coverage for advancing regiments, as well

as rearguard and forward reconnaissance duties for units on the move. Because

she joined an elite unit, Sampson's disguise was more likely to succeed,

since no one was likely to look for a woman among soldiers who were specially

chosen for their above average size and superior physical ability.

Sampson fought in several skirmishes. During her first

battle, on July 3, 1782, outside Tarrytown, New York, she took two musket

balls in her thigh and a cut on her forehead. She begged her fellow soldiers

to let her die and not take her to a doctor, but a soldier put her on his

horse and took her to a hospital. The doctors treated her head wound, but

she left the hospital before they could attend to her leg. Fearful that

her identity would be discovered, she removed one of the balls herself

with a penknife and sewing needle, but the other one was too deep for her

to reach. Her leg never fully healed. On April 1, 1783, she was reassigned

to new duties, and spent seven months serving as a waiter to General John

Paterson.

The war was thought to be over following the Battle of

Yorktown, but since there was no official peace treaty, the Continental

Army remained in uniform. On June 24, the President of Congress ordered

George Washington to send a contingent of soldiers under Paterson to Philadelphia

to help quell a rebellion of American soldiers who were protesting delays

in receiving their pay and discharges. During the summer of 1783, Sampson

became ill in Philadelphia and was cared for by Doctor Barnabas Binney

(1751–1787). He removed her clothes to treat her and discovered the cloth

she used to bind her breasts. Without revealing his discovery to army authorities,

he took her to his house, where his wife, daughters, and a nurse took care

of her.

In September 1783, following the signing of the Treaty

of Paris, November 3 was set as the date for soldiers to muster out. When

Dr. Binney asked Deborah to deliver a note to General Paterson, she correctly

assumed that it would reveal her gender. In other cases, women who pretended

to be men to serve in the army were reprimanded, but Paterson gave her

an honorable discharge, a note with some words of advice, and enough money

to travel home. She was discharged at West Point, New York, on October

25, 1783, after a year and a half of service.

An Official Record of Deborah Gannet's service as "Robert

Shirtliff" from May 20, 1782 to Oct 25, 1783 appears in the "Massachusetts

Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War" series.

Marriage

Deborah Sampson was married in Stoughton, Massachusetts,

to Benjamin Gannett (1757–1827), a farmer from Sharon, Massachusetts, on

April 7, 1785. They had three children: Earl (1786), Mary (1788), and Patience

(1790). They also adopted Susanna Baker Shepard, an orphan. They farmed

on land that had been in Gannett's family for generations; their farm was

smaller than average, and the land was not productive because it had been

worked extensively. These factors, coupled with the depression in the post-war

economy, left the family on the edge of poverty.

Final years and death

In January 1792, Sampson petitioned the Massachusetts

State Legislature for pay which the army had withheld from her because

she was a woman. The legislature granted her petition and Governor John

Hancock signed it. The legislature awarded her 34 pounds plus interest

back to her discharge in 1783.

In 1802, Sampson began giving lectures about her wartime

service. She began by extolling the virtues of traditional gender roles

for women, but toward the end of her presentation she left the stage, returned

dressed in her army uniform, and then performed a complicated and physically

taxing military drill and ceremony routine. She performed both to earn

money and to justify her enlistment, but even with these speaking engagements,

she was not making enough money to pay her expenses. She frequently had

to borrow money from her family and from her friend Paul Revere. Revere

also wrote letters to government officials on her behalf, requesting that

she be awarded a pension for her military service and her wounds.

In 1804, Revere wrote to U.S. Representative William Eustis

of Massachusetts on Sampson's behalf. A military pension had never been

requested for a woman. Revere wrote: "I have been induced to enquire her

situation, and character, since she quit the male habit, and soldiers uniform;

for the more decent apparel of her own gender...humanity and justice obliges

me to say, that every person with whom I have conversed about her, and

it is not a few, speak of her as a woman with handsome talents, good morals,

a dutiful wife, and an affectionate parent".[19] On March 11, 1805, Congress

approved the request and placed Sampson on the Massachusetts Invalid Pension

Roll at the rate of four dollars a month.

On February 22, 1806, Sampson wrote once more to Revere

requesting a loan of ten dollars: "My own indisposition and that of my

sons causes me again to solicit your goodness in our favor though I, with

Gratitude, confess it rouses every tender feeling and I blush at the thought

of receiving ninety and nine good turns as it were—my circumstances require

that I should ask the hundredth." He sent the ten dollars.

In 1809, she sent another petition to Congress, asking

that her pension as an invalid soldier be modified to start from her discharge

in 1783. Had her petition been approved, she would have been awarded back

pay of $960—approximately $13,800 in 2016 ($48 a year for 20 years). Her

petition was denied, but when it came before Congress again in 1816 an

award of $76.80 a year (about $1,100 in 2016 dollars) was approved. With

this amount, she was able to repay all her loans and make improvements

to the family farm.

Sampson died of yellow fever at the age of 66 on April

29, 1827, and was buried at Rock Ridge Cemetery in Sharon, Massachusetts.

Legacy

Memorials

Sharon, Massachusetts now memorializes Sampson with a

statue in front of the public library, the Deborah Sampson Park, and the

"Deborah Sampson Gannett" House, which is privately owned and not open

to the public. The farmland around the home is protected to ensure no development

occurs on the historic homestead.

In 1906, the town of Plympton, Massachusetts with the

Deborah Sampson Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, placed

a boulder on the town green, with a bronze plaque inscribed to Sampson's

memory.

During World War II the Liberty Ship S.S. Deborah Gannett

(2620) was named in her honor. It was laid down March 10, 1944, launched

April 10, 1944 and scrapped in 1962.

As of 2001, the town flag of Plympton incorporates Sampson

as the Official Heroine of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Portrayals in art, entertainment, and media

Portrait of Deborah: A Drama in Three Acts (1959) is a

play by Charles Emery that made its debut at the Camden Hills Theatre,

Camden, Maine, on February 19, 1959.

I'm Deborah Sampson: A Soldier of the Revolution by Patricia

Clapp (1977) is a fictional account of her early life and experience in

the Revolutionary War.

Sampson is portrayed by Whoopi Goldberg in episode 34

of Liberty's Kids entitled "Deborah Sampson: Soldier of the Revolution."

Alex Myers, a descendant of Sampson's, published Revolutionary

(2014), a fictionalized account of her life.

On July 7, 2016, historian/journalist Allison L. Cowan

presented "Deborah Sampson: Continental Army soldier", a biographical talk

for that week's First Thursdays at Saint Paul's Church National Historic

Site.

In her speech at the Democratic National Convention on

July 26, 2016, Meryl Streep named Sampson in a list of women who had made

history.

Deborah Sampson's story, as narrated by Paget Brewster,

was re-enacted in the Season 5 premiere of Drunk History. Evan Rachel Wood

portrayed Sampson.

|

Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock - from

Wikipedia

Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock (March 10, 1839 or 1842,

Avery County, North Carolina – March 9, 1901 or 1903, Watauga County, North

Carolina) was a female soldier during the American Civil War. Despite originally

being a sympathizer for the right of secession, she fought bravely on both

sides. She followed her husband by joining the CSA's 26th North Carolina

Regiment, disguising herself as a young male soldier named Samuel Blalock.

The couple eventually escaped by crossing Confederate lines and joining

the Union partisans in the mountains of western North Carolina. During

the last years of the war, she was a pitiless pro-Union marauder, tormenting

the Appalachia region. Today she's one of the most remembered female combatants

of the Civil War.

Early life

Sarah Malinda Pritchard was born March 10, 1839, in Caldwell

County, North Carolina—now part of Avery County—which is located in the

steep region of Grandfather Mountain and died March 9, 1903. She was the

daughter of John and Elizabeth Pritchard, and the sixth of nine children.

When she was a child, Malinda Pritchard resided in Watauga

County—also now Avery County—which was her main residence until her death.

There, she attended a single-room schoolhouse.

Marriage to Keith Blalock

In those years, she became a close friend of William

McKesson Blalock, whose family had been rivals with her family for over

100 years. Ten years Malinda's senior, Blalock was nicknamed "Keith" after

a great contemporary boxer, due to his skill at boxing. Keith and Malinda

met in school and were childhood |

Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock.

She's holding the picture of

her husband Keith. |

sweethearts. At age 19, she married William in the politically

turbulent 1861, causing a big stir around the families then.

Civil War

After the Civil War had begun, the inhabitants of the

western North Carolina communities—in the Appalachian Mountains—were restlessly

confronted over their eventual political adherences. Daily, the neighbors

argued aggressively with each other, even against their folk people. For

example, originally, Malinda expressed her sympathy for the right of secession.

On the opposite political side, Keith and his stepfather Austin Coffey

were radical unionists—even though Keith was opposed to President Lincoln—and

they had planned to desert toward the Union someday. The Blalocks' opposing

views did not affect their marriage, however.

On time, the Confederate 26th North Carolina Infantry,

commanded by Colonel Zebulon Vance, showed up in the region, to recruit

the strongest men in those communities. Keith began to plan an escape across

the frontier from his southern political enemies. He was hesitant, though,

about whether he would flee directly toward Kentucky or enroll temporarily

with the Confederate Army to desert across the enemy lines later.

Keith also considered the consequences of an untimely

escape on his beloved Malinda. While spurred by the good pay in serving

the "Greys", Keith trusted that he would receive a light military commission

eventually—to northern Virginia for example—from where it would be easy

to desert to the first "Yankee" regiment around. Therefore, with feignedly

gaudy attitude, he accompanied many of his neighbors to the recruitment

office, signing up with the Confederate infantry.

Samuel Blalock

Instead of separating from her beloved Keith, Malinda

decided to escape with him by enrolling in the 26th infantry too. She secretly

dressed as a young man, cutting her hair and wearing male clothing.

Fearing for Malinda, Keith had made sure that all local

secessionists could see him while leaving his hometown with the Confederates.

However, when arriving at the enlistment gathering at the town's railroad

depot, someone began to walk by his side, a mysterious recruit who was

wearing a forage cap and had a particularly little physique and delicate

features. Surprisingly, "He" turned out to be Malinda, his own wife.

Malinda was officially registered on March 20 of 1862

at Lenoir, North Carolina, as a certain "Samuel 'Sammy' Blalock" who supposedly

was Keith's 20-year-old brother. This document and her discharge papers

survive as one of the few existing records of a female soldier from North

Carolina, from the many ones who may have actually served.

Confederate military life

An early bitter fact for Malinda and Keith was that their

plan to defect was unworkable because, already before their arrival, the

26th had fought its biggest battle, which was the loss to the Union of

the town of New Bern in eastern North Carolina. Therefore, instead of moving

to Virginia's battlefront, they remained stationed—far from the northern

frontier—at Kinston, North Carolina, on the Neuse River.

While maintaining her hidden identity, Malinda was a good

soldier. One of their assistant surgeons, named Underwood, pointed out

that "her disguise was never penetrated. She drilled and did the duties

of a soldier as any other member of the Company, and was very adept at

learning the manual and drill."

Keith kept the secret through the months that they shared

the daily rudeness of the military life, such as like living in a tent.

Later, he became a respected brevet sergeant, ordering Malinda then to

"stay close to him". They fought in three battles together, but "Samuel"'s

true identity remained still unknown.

The desertion

In April 1862, Keith's squad received the order to range

the Neuse River's region by fording it during the night, to detect any

enemy guarding-posts. Their ultimate objective was to track down the location

of a particular Union regiment commanded by US General Ambrose Burnside.

At one point of the mission, a hard skirmish began. Most

of Keith's squad retreated to safety, crossing back over the Neuse River.

However, after regrouping, it was found that "Samuel" was missing. Keith

promptly returned to the battlefield. He found Malinda clinging to a pine

and bleeding profusely, with a bullet lodged in her left shoulder.

As quickly as he could, Keith carried Malinda back to

the 26th in his arms. He brought her to the infirmary tent where she was

attended by its surgeon, Dr. Thomas J. Boykin. The bullet was successfully

removed, but the truth about "Samuel" was also discovered at Boykin's examination.

Keith obtained the promise from Boykin that he would spare

them some time before reporting this. Desperately, Keith rushed to the

forest on that night, to a nearby field of poison ivy. He stripped his

clothes and flailed through the underbrush, for about half an hour.

The next morning, he suffered a persistent fever while

his affected skin was inflamed and covered by blisters. Keith told the

doctors that he had a serious recurrent illness which was highly contagious,

adding the ailment of a hernia also. Fearing an outbreak of smallpox, the

doctors discharged Keith expeditiously from the regiment and confined him

to his tent.

However, Malinda would remain stranded in the camp because

her recent wound didn't yet merit a discharge. She decided to confront

Colonel Vance once and for all. She offered herself as a volunteer to aid

the sick Sergeant Keith on his return to Watauga. Vance's response was

a clear "no", communicating to "Samuel" that instead "he" would be his

new personal orderly.

At that point Malinda decided to tell Vance the truth

about her gender. Vance's first reaction was of disbelief while calling

the surgeon and commenting to him: "Oh Surgeon, have I a case for you!"

However, the physician corroborated the seriousness of Malinda's statement.

Immediately, Vance discharged "Samuel" and demanded the restitution of

"his" original enlisting reward of 50 dollars.

Marauders

Malinda and her husband could return to Watauga then.

Once there, though, Keith was soon required by the local Confederate forces,

which demanded that he enlist again—after noting his healthy status—and

return to the front. Otherwise, he would be judged by the new Confederate

laws of military draft.

Therefore, Malinda and Keith fled again, toward Grandfather

Mountain. There, they found more local deserters in the same condition.

They stayed with them until the Confederate Army intercepted the group,

injuring Keith in his arm.

Malinda and Keith moved then to Tennessee, where they

joined the US-10th Michigan Cavalry of Colonel George Washington Kirk,

who was later succeeded by General George Stoneman. For some time, Keith

accomplished some administrative chores as a recruitment agent.

However, the couple decided to enter in action again,

this time for the Union, by joining Colonel Kirk's voluntary guerrilla

squadrons which were accomplishing some scouting and raiding missions throughout

the Appalachia region of North Carolina.

Always with Malinda next to him, Keith began in Blowing

Rock, North Carolina, as one of the leaders of the guides for the Watauga

Underground Railroad. This was a way of escape from the Confederate jail

at Salisbury, North Carolina, which was the largest facility of the state.

Keith had to guide the escaped Union soldiers to safety in Tennessee. However,

from 1863 on, the skirmishes against the patrolling enemy forces in the

region were increasingly tougher.

Keith's pro-union guerrilla forces began then to torment

Watauga County with no mercy. Because once they had been harshly humbled

by the southern loyalists, the outlaws pitilessly raided their farms, stole

and killed. Marauding throughout North Carolina's Appalachia region, they

were soon feared by the entire state.

Confederate vigilantes then murdered Keith's stepfather,

Austin Coffey, and one of Austin's four brothers (William), while the other

two survived the attack. The Coffeys had been betrayed by some local folks

who were found and killed by Keith after the war.

During the war, some of the most ill-fated actions of

Malinda and Keith were their two pillaging incursions to the Moore family's

farm in Caldwell County, late in 1863. One of Moore's sons, James Daniel,

was the 26th's officer who recruited them originally. In the first incursion,

Malinda was injured in her shoulder. During the second one, Moore's son

was at home, recovering after the Battle of Gettysburg, while Keith got

a shot in his eye and lost it.

During the war, Keith lost the use of a hand. He also

murdered one of his uncles who had turned to the Confederacy.

Later life

After the war, Malinda and Keith returned to Watauga,

to live the rest of their lives as farmers, with their four children. For

some time, they had troubles getting Keith's government pension. Afterward,

they joined the Republican Party where, in 1870, Keith ran unsuccessfully

for a place in the Congress of the United States.

Sarah Malinda Pritchard Blalock died in 1901, at age 59,

due to natural causes while she was sleeping. She was buried in the Montezuma

Cemetery of Avery County. Very affected, Keith moved to Hickory, North

Carolina, taking his son Columbus with him.

On April 11, 1913, Keith died in a railroad accident.

He lost control of his handcar on a curve, and was crushed to death. Some

versions attribute his death to a local payback for his past years with

Malinda. He was buried beside her at Montezuma Cemetery. His stone badge

reads: "Keith Blalock, Soldier, 26th N.C Inf., CSA."

|

.

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|