History of rail transport in the United States - from

Wikipedia

| Wooden railroads, called wagonways were built in Unites

States starting from 1720s. A railroad was reportedly used in the construction

of the French fortress at Louisburg, Nova Scotia in 1720. Between 1762

and 1764, at the close of the French and Indian War, a gravity railroad

(mechanized tramway) (Montresor's Tramway) is built by British military

engineers up the steep riverside terrain near the Niagara River waterfall's

escarpment at the Niagara Portage (which the local Senecas called "Crawl

on All Fours.") in Lewiston, New York.

Railroads played a large role in the development of the

United States from the industrial revolution in the North-east (1810–1850)

to the settlement of the West (1850–1890). The American railroad mania

began with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1828 and flourished until

the Panic of 1873 bankrupted many companies and temporarily ended growth.

Although the South started early to build railways, it

concentrated on short lines linking cotton regions |

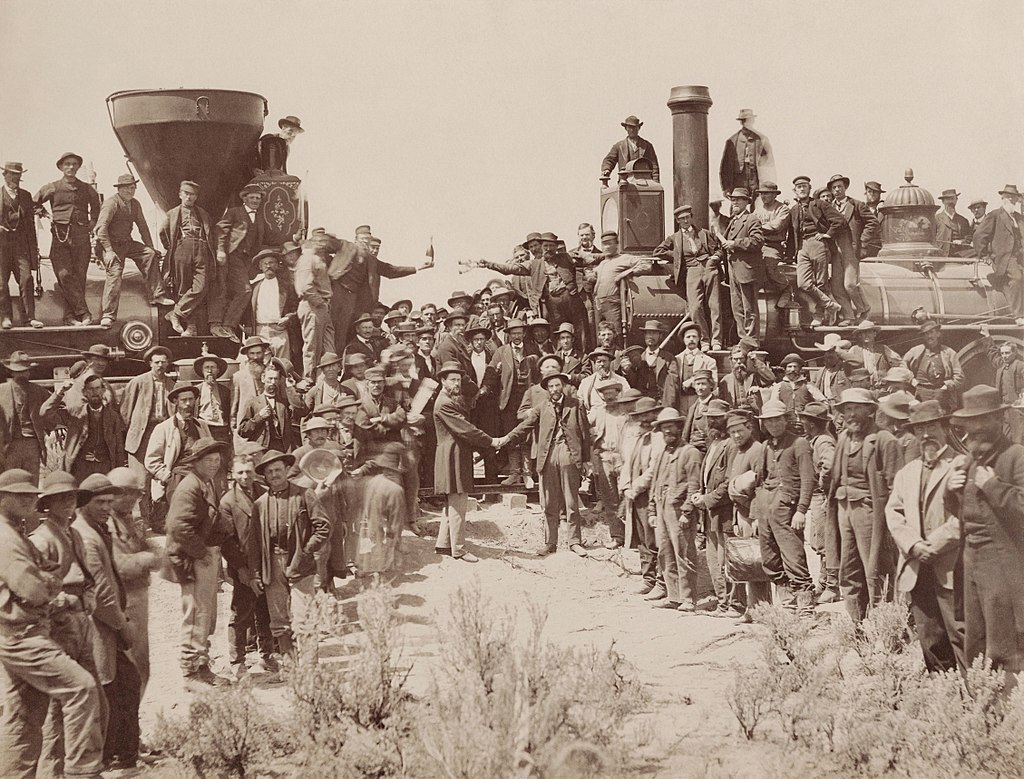

The First Transcontinental Railroad

was completed in 1869. |

to oceanic or river ports, and the absence of an interconnected

network was a major handicap during the Civil War. The North and Midwest

constructed networks that linked every city by 1860. In the heavily settled

Midwestern Corn Belt, over 80 percent of farms were within 5 miles (8 km)

of a railway, facilitating the shipment of grain, hogs, and cattle to national

and international markets. A large number of short lines were built, but

thanks to a fast developing financial system based on Wall Street and oriented

to railway bonds, the majority were consolidated into 20 trunk lines by

1890. State and local governments often subsidized lines, but rarely owned

them.

The system was largely built by 1910, but then trucks

arrived to eat away the freight traffic, and automobiles (and later airplanes)

to devour the passenger traffic. After 1940, the use of diesel electric

locomotives made for much more efficient operations that needed fewer workers

on the road and in repair shops.

A series of bankruptcies and consolidations left the rail

system in the hands of a few large operations by the 1980s. Almost all

long-distance passenger traffic was shifted to Amtrak in 1971, a government-owned

operation. Commuter rail service is provided near a few major cities such

as New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and the District

of Columbia. Computerization and improved equipment steadily reduced employment,

which peaked at 2.1 million in 1920, falling to 1.2 million in 1950 and

215,000 in 2010. Route mileage peaked at 254,251 miles (409,177 km) in

1916 and fell to 139,679 miles (224,792 km) in 2011.

Freight railroads continue to play an important role in

the United States' economy, especially for moving imports and exports using

containers, and for shipments of coal and, since 2010, of oil. According

to the British news magazine The Economist, "They are universally recognized

in the industry as the best in the world." Productivity rose 172% between

1981 and 2000, while rates rose 55% (after accounting for inflation). Rail's

share of the American freight market rose to 43%, the highest for any rich

country.

Chronological history

Early period (1720–1825)

The animal powered Leiper Railroad followed in 1810 after

the preceding successful experiment — designed and built by merchant Thomas

Leiper, the railway connects Crum Creek to Ridley Creek, in Delaware County,

Pennsylvania. It was used until 1829, when it was temporarily replaced

by the Leiper Canal, then is reopened to replace the canal in 1852. This

became the Crum Creek Branch of the Baltimore and Philadelphia Railroad

(part of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad) in 1887. This is the first railroad

meant to be permanent, and the first to evolve into trackage of a common

carrier after an intervening closure.

In 1826 Massachusetts incorporated the Granite Railway

as a common freight carrier to primarily haul granite for the construction

of the Bunker Hill Monument; operations began later that year.

Other railroads authorized by states in 1826 and constructed

in the following years included the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company's

gravity railroad; and the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, to carry freight

and passengers around a bend in the Erie Canal. To link the port of Baltimore

to the Ohio River, the state of Maryland in 1827 chartered the Baltimore

and Ohio Railroad (B&O), the first section of which opened in 1830.

Similarly, the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company was chartered

in 1827 to connect Charleston to the Savannah River, and Pennsylvania built

the Main Line of Public Works between Philadelphia and the Ohio River.

The Americans closely followed and copied British railroad

technology. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier

and started passenger train service in May 1830, initially using horses

to pull train cars.[7]:90 The South Carolina Canal and Rail Road Company

was the first to use steam locomotives regularly beginning with the Best

Friend of Charleston, the first American-built locomotive intended for

revenue service, in December 1830.

The B&O started developing steam locomotives in 1829

with Peter Cooper's Tom Thumb.[8] This was the first American-built locomotive

to run in the U.S., although it was intended as a demonstration of the

potential of steam traction rather than as a revenue-earning locomotive.[7]:96

Many of the earliest locomotives for American railroads were imported from

England, including the Stourbridge Lion and the John Bull, but a domestic

locomotive manufacturing industry was quickly established, with locomotives

like the DeWitt Clinton being built in the 1830s.[9] The B&O's westward

route reached the Ohio River in 1852, the first eastern seaboard railroad

to do so.

By 1850, 9,000 miles (14,000 km) of railroad lines had

been built. The federal government operated a land grant system between

1855 and 1871, through which new railway companies in the uninhabited West

were given millions of acres they could sell or pledge to bondholders.

A total of 129 million acres (520,000 km2) were granted to the railroads

before the program ended, supplemented by a further 51 million acres (210,000

km2) granted by the states, and by various government subsidies. This program

enabled the opening of numerous western lines, especially the Union Pacific-Central

Pacific with fast service from San Francisco to Omaha and east to Chicago.

West of Chicago, many cities grew up as rail centers, with repair shops

and a base of technically literate workers.

Railroads soon replaced many canals and turnpikes and

by the 1870s had significantly displaced steamboats as well. The railroads

were superior to these alternative modes of transportation, particularly

water routes because they lowered costs in two ways. Canals and rivers

were unavailable in the winter season due to freezing, but the railroads

ran year-round despite poor weather. And railroads were safer: the likelihood

of a train crash was less than the likelihood of a boat sinking. The railroads

provided cost-effective transportation because they allowed shippers to

have a smaller inventory of goods, which reduced storage costs during winter,

and to avoid insurance costs from the risk of losing goods during transit.

Likewise, railroads changed the style of transportation.

For the common person in the early 1800s, transportation was often travel

by horse or stage coach. The network of trails along which coaches navigated

were riddled with ditches, potholes, and stones. This made travel fairly

uncomfortable. Adding to injury, coaches were cramped with little leg room.

Travel by train offered a new style. Locomotives proved themselves a smooth,

headache free ride with plenty of room to move around. Some passenger trains

offered meals in the spacious dining car followed by a good night sleep

in the private sleeping quarters. Railroad companies in the North and Midwest

constructed networks that linked nearly every major city by 1860. In the

heavily settled Corn Belt (from Ohio to Iowa), over 80 percent of farms

were within 5 miles (8.0 km) of a railway. A large number of short lines

were built, but thanks to a fast developing financial system based on Wall

Street and oriented to railway securities, the majority were consolidated

into 20 trunk lines by 1890. Most of these railroads made money and ones

that didn't were soon bought up and incorporated in a larger system or

"rationalized". Although the transcontinental railroads dominated the media,

with the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 dramatically

symbolizing the nation’s unification after the divisiveness of the Civil

War, most construction actually took place in the industrial Northeast

and agricultural Midwest, and was designed to minimize shipping times and

costs. The railroads in the South were repaired and expanded and then,

after a lot of preparation, changed from a 5-foot gauge to standard gauge

of 4 foot 8 ½ inches in two days in May 1886.

With its extensive river system the United States supported

a large array of horse-drawn or mule-drawn barges on canals and paddle

wheel steamboats on rivers that competed with railroads after 1815 until

the 1870s. The canals and steamboats lost out because of the dramatic increases

in efficiency and speed of the railroads, which could go almost anywhere

year round. The railroads were faster and went to many places a canal would

be impractical or too expensive to build or a natural river never went.

Railroads also had better scheduling since they often could go year round,

more or less ignoring the weather. Canals and river traffic were cheaper

if you lived on or near a canal or river that wasn't frozen over part of

the year; but only a few did. Long distance transport of goods by wagon

to a canal or river was slow and expensive. A railroad to a city made it

an inland "port" that often prospered or turned a town into a city.

Civil War and Reconstruction (1861–1877)

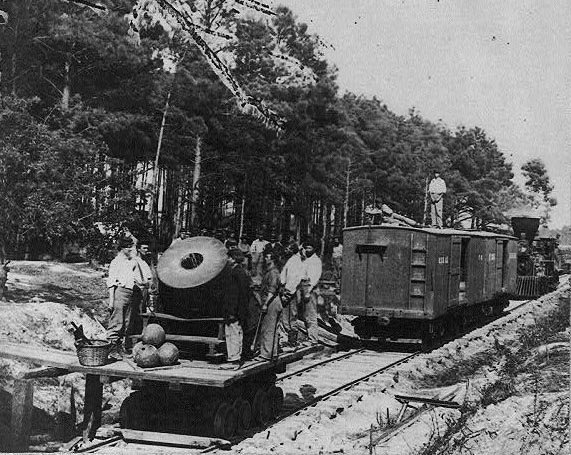

| Rail was strategic during the American Civil War, and

the Union used its much larger system much more effectively. Practically

all the mills and factories supplying rails and equipment were in the North,

and the Union blockade kept the South from getting new equipment or spare

parts. The war was fought in the South, and Union raiders (and sometimes

Confederates too) systematically destroyed bridges and rolling stock —

and sometimes bent rails — to hinder the logistics of the enemy.

In the South, most railroads in 1860 were local affairs

connecting cotton regions with the nearest waterway. Most transport was

by boat, not rail, and after the Union blockaded the ports in 1861 and

seized the key rivers in 1862, long-distance travel was difficult. The

outbreak of war had a depressing effect on the economic fortunes of the

railroad companies, for the hoarding of the cotton crop in an attempt to

force European intervention left railroads bereft of their main source

of income. Many had to lay off employees, and in particular, let go skilled

technicians and engineers. For the early years of the war, the Confederate

government had a hands-off approach to the railroads. Only in mid-1863

did the Confederate government initiate an overall policy, and it was confined

solely to aiding the war effort. With the legislation of impressment the

same year, railroads and their rolling stock came under the de facto |

A mortar mounted on a railroad

car used during the Civil War, 1865. |

control of the Confederate military.

Conditions deteriorated rapidly in the Confederacy, as

there was no new equipment and raids on both sides systematically destroyed

key bridges, as well as locomotives and freight cars. Spare parts were

cannibalized; feeder lines were torn up to get replacement rails for trunk

lines, and the heavy use of rolling stock wore them out. In 1864-65 the

Confederate railroad network collapsed; little traffic moved in 1865.

Ceremony for the completion of the

First Transcontinental Railroad,

May 1869. |

The Southern states had blocked westward rail expansion

before 1860, but after secession the Pacific Railway Acts were passed in

1862, allowing the first transcontinental railroad to be completed in 1869,

making possible a six-day trip from New York to San Francisco. Other transcontinentals

were built in the South (Southern Pacific, Santa Fe) and along the Canada–US

border (Northern Pacific, Great Northern), accelerating the settlement

of the West by offering inexpensive farms and ranches on credit, carrying

pioneers and supplies westward, and cattle, wheat and minerals eastward.

During the Reconstruction era, Northern money financed

the rebuilding and dramatic expansion of railroads throughout the South;

they were modernized in terms of track gauge, equipment and standards of

service. The Southern network expanded from 11,000 miles (17,700 km) in

1870 to 29,000 miles (46,700 km) in 1890. The lines were owned and directed

overwhelmingly by Northerners. Railroads helped create a mechanically skilled

group of craftsmen and broke the isolation of much of the region. Passengers

were few, however, and apart from hauling the cotton crop when it was harvested,

there was little freight traffic. |

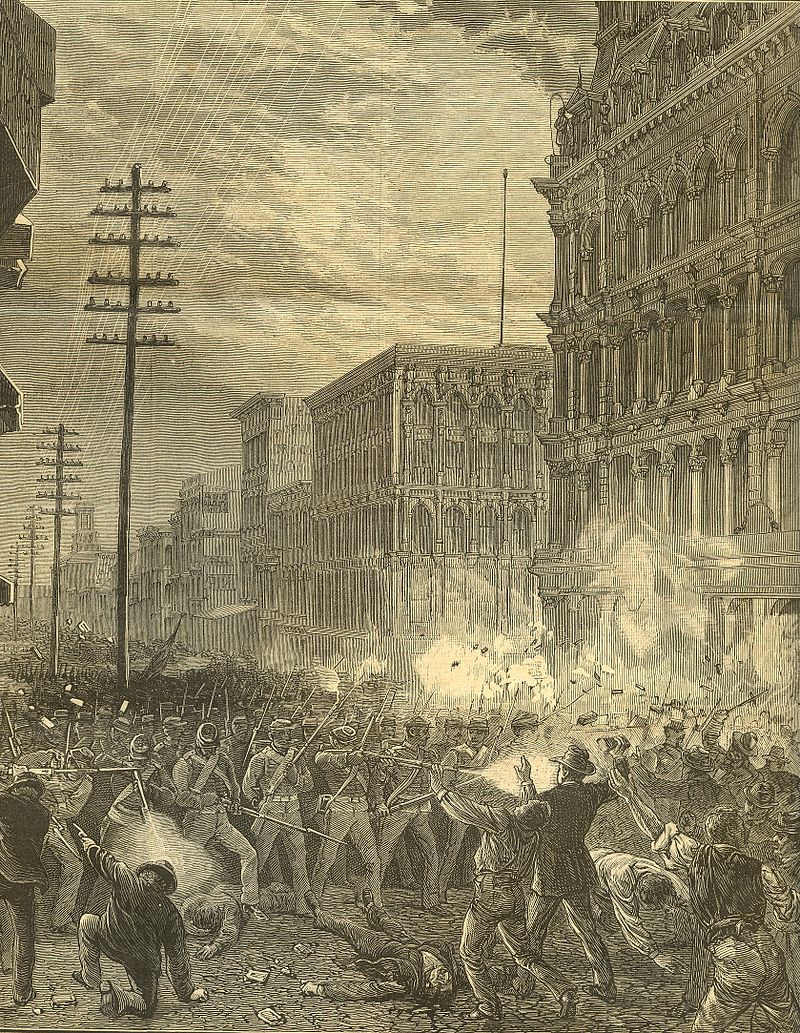

Strikers in Baltimore confronting the

Maryland National Guard, July 1877. |

The Panic of 1873 was a major global economic depression

which ended rapid rail expansion in the United States. Many lines went

bankrupt or were barely able to pay the interest on their bonds, and workers

were laid off on a mass scale, with those still employed subject to large

cuts in wages. This worsening situation for railroad workers led to strikes

against many railroads, culminating in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

The Great Strike began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West

Virginia, in response to the cutting of wages for the second time in a

year by the B&O Railroad. The strike, and related violence, spread

to Cumberland, Maryland, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, Philadelphia,

Chicago and the Midwest. The strike lasted for 45 days, and ended only

with the intervention of local and state militias, and federal troops.

Labor unrest continued into the 1880s, such as the Great Southwest Railroad

Strike of 1886, which involved over 200,000 workers.

Expansion and consolidation (1878–1916)

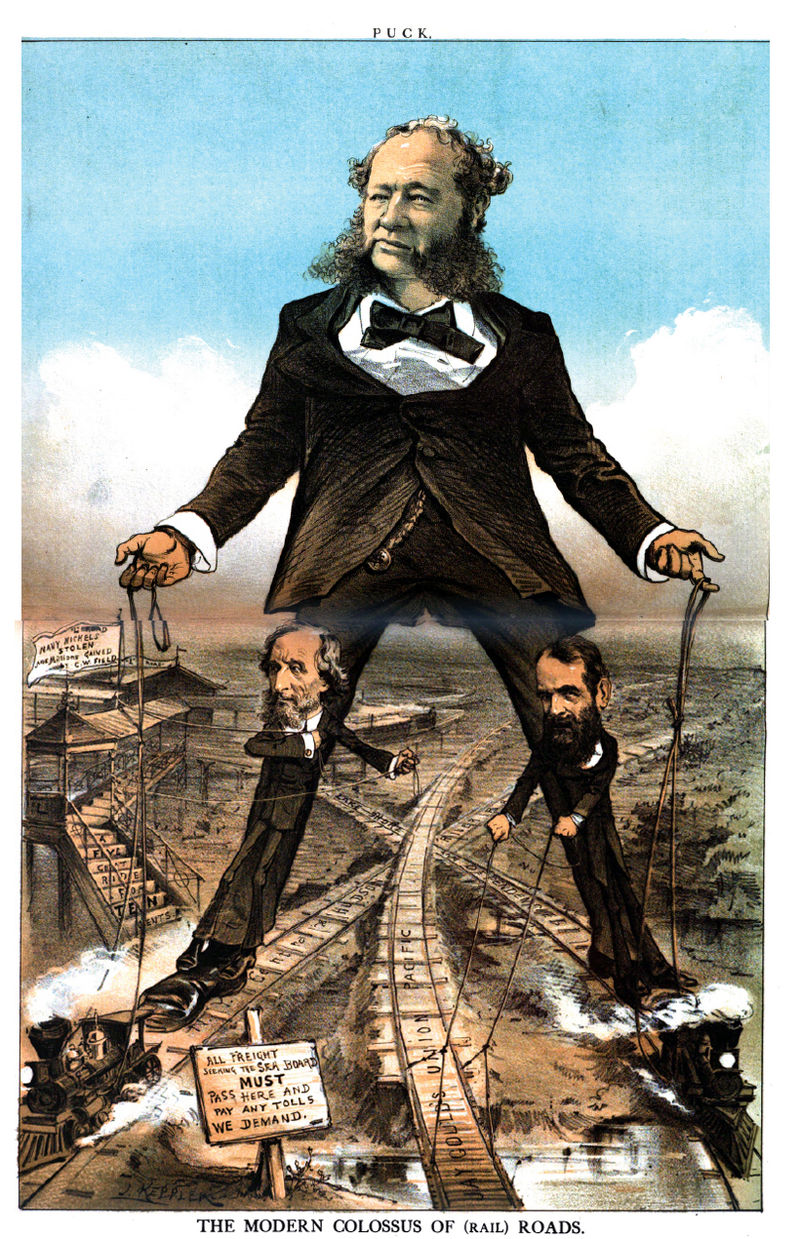

1879 cartoon depicting

William Henry Vanderbilt

as "The Modern Colossus

of (Rail) Roads." |

By 1880 the nation had 17,800 freight locomotives carrying

23,600 tons of freight, and 22,200 passenger locomotives. The U.S. railroad

industry was the nation's largest employer outside of the agricultural

sector. The effects of the American railways on rapid industrial growth

were many, including the opening of hundreds of millions of acres of very

good farm land ready for mechanization, lower costs for food and all goods,

a huge national sales market, the creation of a culture of engineering

excellence, and the creation of the modern system of management.

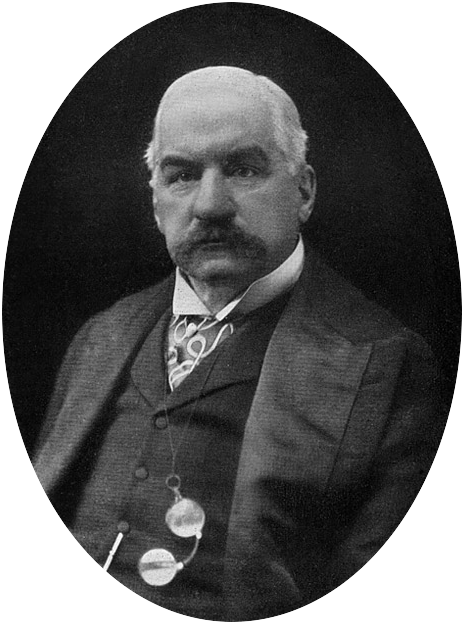

New York financier J.P. Morgan played an increasingly

dominant role in consolidating the rail system in the late 19th century.

He orchestrated reorganizations and consolidations in all parts of the

United States. Morgan raised large sums in Europe, but instead of only

handling the funds, he helped the railroads reorganize and achieve greater

efficiencies. He fought against the speculators interested in speculative

profits, and built a vision of an integrated transportation system. In

1885, he reorganized the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railroad, leasing

it to the New York Central. In 1886, he reorganized the Philadelphia &

Reading, and in 1888 the Chesapeake & Ohio. He was heavily involved

with railroad tycoon James J. Hill and the Great Northern Railway.

Industrialists such as Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt and

Jay Gould became wealthy through railroad ownerships, as large railroad

companies such as the Grand Trunk |

J.P. Morgan |

Railway and the Southern Pacific Transportation Company spanned

several states. In response to monopolistic practices and other excesses

of some railroads and their owners, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce

Act and created the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1887. The ICC

indirectly controlled the business activities of the railroads through

issuance of extensive regulations.

Morgan set up conferences in 1889 and 1890 that brought

together railroad presidents in order to help the industry follow the new

laws and write agreements for the maintenance of "public, reasonable, uniform

and stable rates." The conferences were the first of their kind, and by

creating a community of interest among competing lines paved the way for

the great consolidations of the early 20th century. Congress responded

by enacting antitrust legislation to prohibit monopolies of railroads (and

other industries), beginning with the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890.

The Panic of 1893 was the largest economic depression

in U.S. history at that time. It was the result of railroad overbuilding

and shaky railroad financing, which set off a series of bank failures.

One-quarter of U.S. railroads had failed by mid-1894, representing over

40,000 miles (64,000 km). The failed lines included the Northern Pacific

Railway, the Union Pacific Railroad and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa

Fe Railroad. Acquisitions of the bankrupt companies led to further consolidation

of ownership. As of 1906, two-thirds of the rail mileage in the U.S. was

controlled by seven entities, with the New York Central, Pennsylvania Railroad

(PRR), and Morgan having the largest portions.

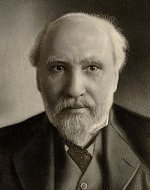

James J. Hill |

James J. Hill joined forces with Morgan and others to

gain control of the Northern Pacific. Hill formed the Northern Securities

Company to consolidate the operations of the Northern Pacific with Hill's

own Great Northern, but President Theodore Roosevelt, a trust-buster, strongly

disapproved and took it to court. In 1904 the federal courts dissolved

the Northern Security company (see Northern Securities Co. v. United States)

and the railroads had to go their separate, competitive ways. By that time

Morgan and Hill had ensured the Northern Pacific was well-organized and

able to survive easily on its own.

In 1901 the Union Pacific Railroad acquired all of the

stock of the Southern Pacific. The Federal government charged UP with violating

the Sherman Act, and in 1913 the Supreme Court ordered UP to divest itself

of all SP stock. This ruling was received with considerable alarm throughout

the industry, as UP and SP |

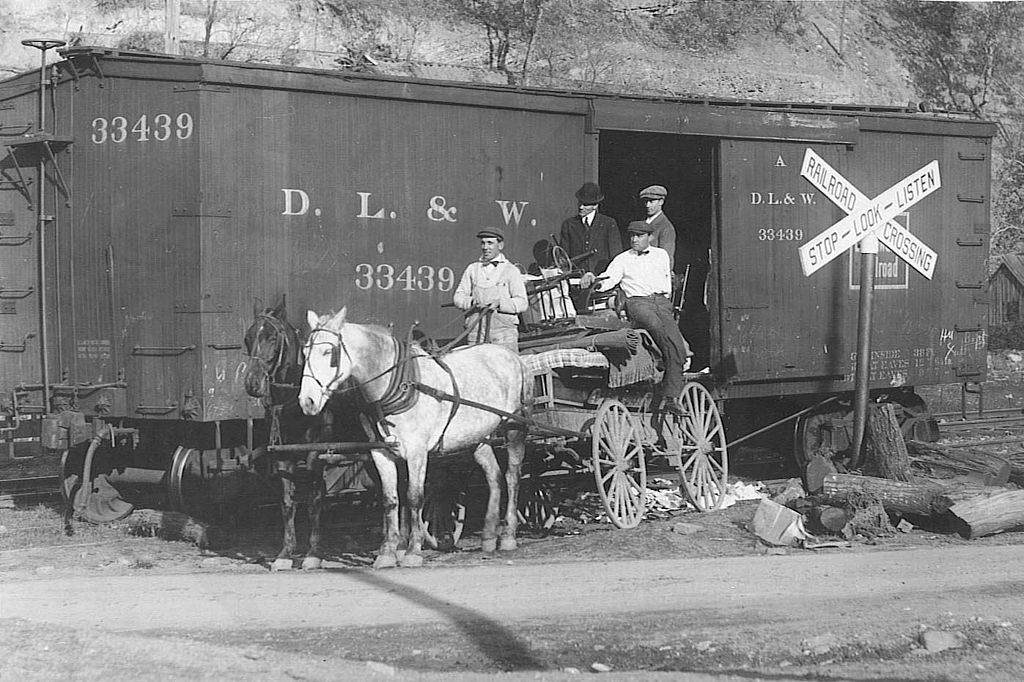

A Delaware, Lackawanna and

Western Railroad wagon at a

level crossing, circa 1900 |

were widely considered at that time not to be significant

competitors. (Later in the 20th century, with different economic conditions

and changes in the law, UP successfully acquired the SP. See Resurgence

of freight railroads.)

Continuing concern over rate discrimination by railroads

led Congress to enact additional laws, giving increased regulatory powers

to the ICC. The 1906 Hepburn Act gave the ICC authority to set maximum

rates and review the companies' financial records.

Nationalized management (1917–1920)

The United States Railroad Administration (USRA) temporarily

took over management of railroads during World War I to address inadequacy

in critical facilities throughout the overall system, such as terminals,

trackage, and rolling stock. President Woodrow Wilson issued an order for

nationalization on December 26, 1917. Management by USRA led to standardization

of equipment, reductions of duplicative passenger services, and better

coordination of freight traffic. Federal control of the railroads ended

in March 1920.

Railroads in the early automobile era (1921–1945)

In the early 20th century, some members of Congress, the

ICC, and some railroad executives developed concerns about inefficiencies

in the American railroad system. Memories of the 1893 panic, the continuing

proliferation of railroad companies, and duplicative facilities, fueled

this concern. To an extent the need to nationalize the system during the

war was an example of this inefficiency. These concerns were the impetus

for legislation to consider improvements to the system. The 1920 Esch-Cummins

Act directed the ICC to prepare and adopt a plan for the consolidation

of the railroad companies into a limited number of systems. In 1929 the

ICC published its proposed Complete Plan of Consolidation, also known as

the "Ripley Plan," after its author, William Z. Ripley of Harvard University.

The agency held hearings on the plan, but none of the proposed consolidations

was ever implemented. Many small railroads failed during the Great Depression

of the 1930s. Of those lines that survived, the stronger ones were not

interested in supporting the weaker ones. In 1940 Congress formally abandoned

the Ripley Plan.

Modern era (1946–present)

During the post-World War II boom many railroads were

driven out of business due to competition from airlines and Interstate

highways. The rise of the automobile led to the end of passenger train

service on most railroads. Trucking businesses had become major competitors

by the 1930s with the advent of improved paved roads, and after the war

they expanded their operations as the Interstate highway network grew,

and acquired increased market share of freight business. Railroads

continued to carry bulk freight such as coal, steel and other commodities.

However, the ICC continued to regulate railroad rates and other aspects

of railroad operations, which limited railroads' flexibility in responding

to changing market forces.

In 1966, Congress created the Federal Railroad Administration,

to issue and enforce rail safety regulations, administer railroad assistance

programs, and conduct research and development in support of improved railroad

safety and national rail transportation policy. The safety functions were

transferred from the ICC. The FRA was established as part of the new federal

Department of Transportation.

Two of the largest remaining railroads, the Pennsylvania

Railroad and the New York Central, merged in 1968 to form the Penn Central.

At the insistence of the ICC the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad

was added to the merger in 1969; in 1970 the Penn Central declared bankruptcy,

the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history until then.[28]:234 Other bankrupt

railroads included the Ann Arbor Railroad (1973), Erie Lackawanna Railway

(1972), Lehigh Valley Railroad (1970), Reading Company (1971), Central

Railroad of New Jersey (1967) and Lehigh and Hudson River Railway (1972).

In 1970 Congress created a government corporation, Amtrak,

to take over operation of Penn Central passenger lines and selected inter-city

passenger services from other private railroads, under the Rail Passenger

Service Act. Amtrak began operations in 1971.

Congress passed the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of

1973 (sometimes called the "3R Act") to salvage viable freight operations

from the bankrupt Penn Central and other lines in the northeast, mid-Atlantic

and midwestern regions, through the creation of the Consolidated Rail Corporation

(ConRail), a government-owned corporation. Conrail began operations in

1976. The 3R Act also formed the United States Railway Association, another

government corporation, taking over the powers of the ICC with respect

to allowing the bankrupt railroads to abandon unprofitable lines.

Amtrak acquired most of the right-of-way and facilities

of the Penn Central Northeast Corridor from Washington, D.C. to Boston,

under the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act (the "4R Act")

of 1976.

In addition to freight railroads, Conrail inherited commuter

rail operations from several predecessor railroads in the northeast, and

these operations continued to be unprofitable. State and local government

transportation agencies took over the passenger operations and acquired

the various rights-of-way from Conrail in 1983.

The National Association of Railroad Passengers, a non-profit

advocacy group, was organized in the late 1960s to support operation of

passenger trains.

Beginning in the late 1970s Amtrak eliminated several

of its lightly-traveled lines. Ridership stagnated at roughly 20 million

passengers per year amid uncertain government aid from 1981 to about 2000.

Ridership increased during the first decade of the 21st century after implementation

of capital improvements in the Northeast Corridor and rises in automobile

fuel costs.

Resurgence of freight railroads in the 1980s

| In 1980 Congress enacted the Staggers Rail Act to revive

freight traffic, by removing restrictive regulations and enabling railroads

to be more competitive with the trucking industry. The Northeast Rail Service

Act of 1981 authorized additional deregulation of northeast railroads.

Among other things, these laws reduced the role of the ICC in regulating

the railroads and allowed the carriers to discontinue unprofitable routes.

More railroad companies merged and consolidated their lines in order to

remain successful. These changes led to the current system of fewer, but

profitable, Class I railroads covering larger regions of the United States.

Since the beginning of the current deregulatory era, the

following Class I railroads have been involved in mergers:

Union Pacific acquired the Missouri

Pacific and Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad in the 1980s, the

Chicago and North Western in 1995,

and the Southern Pacific in 1996

CSX was formed in 1986 from the Chessie

System and the Seaboard System

BNSF Railway was formed in 1996 from

the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe (the "Santa Fe")

and Burlington Northern |

The use of double-stack rail cars

and intermodal containers,

facilitated by deregulation, has

improved railroads' competitiveness |

Norfolk Southern was formed in 1982 from

the Norfolk and Western and Southern Railway

Canadian Pacific acquired the Delaware

and Hudson in 1991

Canadian National acquired the Illinois

Central in 1999

CSX and Norfolk Southern acquired

most of the Conrail freight rail assets in 1997.

In 1995, when most of the ICC's powers had been eliminated,

Congress finally abolished the agency and transferred its remaining functions

to a new agency, the Surface Transportation Board.

21st century

In the early 21st century, several of the railroads, along

with the federal government and various port agencies, began to reinvest

in freight rail infrastructure, such as intermodal terminals and bridge

and tunnel improvements. These projects are designed to increase capacity

and efficiency across the national rail network. See Heartland Corridor

and National Gateway.

Both the Bill Clinton and Barack Obama administrations

had announced plans for new high-speed rail lines in their first terms.

In the case of Clinton era, the only tangible outcome was the introduction

of Amtrak's Acela Express, serving the Northeast Corridor, in 2000. Obama

even mentioned his rail plans in his State of the Union address, the first

time in decades a President had done so. While several small scale improvements

to rail lines were financed by federal money, more ambitious plans in Florida,

Ohio and other states failed when newly elected Republican governors stopped

existing high-speed rail plans and returned federal funding.

In 2015 construction began on the California High-Speed

Rail line. The Phase I portion, which will link Los Angeles and San Francisco

in under three hours, is projected to be complete in 2029.

Technology

| The B&O established its Mount Clare Shops in Baltimore

in 1829. This was the first railroad manufacturing facility in the U.S.,

and the company built locomotives, railroad cars, iron bridges and other

equipment there. Following the B&O example, U.S. railroad companies

soon became self-sufficient, as thousands of domestic machine shops turned

out products and thousands of inventors and tinkerers improved the equipment.

Rail manufacturing

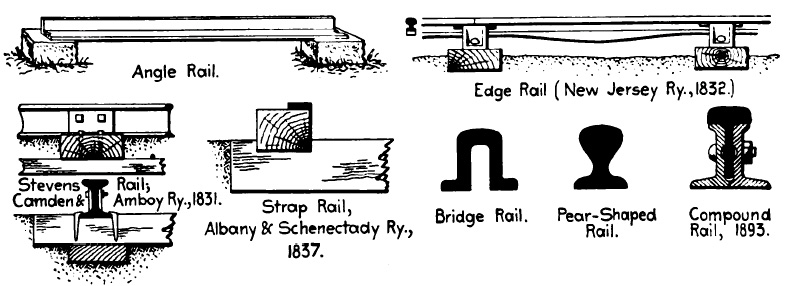

|

Rail profiles used in the

19th century |

In general, U.S. railroad companies imported technology from

Britain in the 1830s, particularly strap iron rails, as there were no rail

manufacturing facilities in the United States at that time. Heavy iron

"T" rails were first manufactured in the U.S. in the mid-1840s at Mount

Savage, Maryland[61] and Danville, Pennsylvania. This improved rail design

permitted higher train speeds and more reliable operation. Discovery of

high-quality iron ores in the mid-19th century, particularly in the Great

Lakes region, led to fabrication of better-quality rails.

Steel rails began to replace iron later in the 19th century.

Several railroads imported steel rails from England in the 1860s, and the

first commercially available steel rails in the U.S. were manufactured

in 1867 at the Cambria Iron Works in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. By the mid-1880s

U.S. railroads were using more steel rails than iron in building new or

replacement tracks.

Track gauge

Through the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, not only local projects,

but long-distance links, were completed, so that by 1860 the eastern half

of the continent, especially the Northeast, was linked by a network of

connecting railroads. However, although England had early adopted a standard

gauge of 4 ft 8 1?2 in (1,435 mm), once Americans started building locomotives,

they experimented with different gauges, resulting in the standard gauge,

or a close approximation, being adopted in the Northeast and Midwest U.S.,

but a 5 ft (1,524 mm) gauge in the South, and a 5 ft 6 in (1,676 mm) gauge

in Canada. In addition, the Erie Railway was built to 6 ft (1,829 mm) broad

gauge, and in the 1870s a widespread movement looked at the cheaper 3 ft

(914 mm) narrow gauge. Except for the latter, gauges were standardized

across North America after the end of the Civil War in 1865.

Locomotives

In the early years American railroads imported many steam

locomotives from England. While the B&O and the PRR built many of their

own steam locomotives, other railroads purchased from independent American

manufacturers. Prominent among the early steam manufacturers were Norris,

Baldwin and Rogers, followed by Lima and Alco later in the 19th and 20th

centuries.

Diesel locomotives were first developed in Europe after

World War I, and U.S. railroads began to use them widely in the 1930s and

1940s. Most U.S. roads discontinued use of steam locomotives by the 1950s.

A diesel engine was expensive to build, but was less complex and easier

to maintain than a steam locomotive, and required only one person to operate.

This meant reduced costs and greater reliability for the railroads. Several

companies developed fast streamliner trains, such as the Super Chief and

the California Zephyr during the 1930s and 1940s. Their locomotives used

either diesel or similar internal combustion engine designs. See Dieselisation

in North America.

Though electric railways expanded in Europe, they never

reached the same popularity in North America. They were built primarily

in the north-west and the north-east beginning in the late 19th century.

While some railroads used electric locomotives for both freight and passenger

trains, by the end of the 20th century most freight trains were pulled

only by diesel locomotives. The Northeast Corridor, the most heavily travelled

passenger line in the US, is one of few long lines currently operating

with electrification. See Railroad electrification in the United States.

Signalling and communications

Early forms of American railroad signaling and communication

were virtually non-existent. Before telegraphs, the American railroads

initially managed their train operations using timetables. However, there

were no means of communication between drivers and dispatchers, and occasionally,

two trains were sent on a collision course, or "cornfield meets." With

the advent of the telegraph in the 1840s, a more sophisticated system was

developed that allowed the dissemination of alterations to the timetable,

known as train orders. These orders overrode the timetable, allowing the

cancellation, rescheduling and addition of trains. The earliest recorded

use of train orders was by the Erie Railroad in 1851.

The development of the electrical track circuit in the

1870s led to the use of systems of block signals, which improved the railroads'

speed, safety and efficiency. Mechanical interlockings, which prevent conflicting

movements at rail junctions and crossings, were also introduced in the

U.S. in the 1870s, after their initial development in Britain.

Labor relations and worker safety

Railways changed employment practices in many ways. Lines

with hundreds or thousands of employees developed systematic rules and

procedures, not only for running the equipment but in hiring, promoting,

paying and supervising employees. The railway system of management was

adopted by all major business sectors. Railways offered a new type of work

experience in enterprises vastly larger in size, complexity and management.

At first workers were recruited from occupations where skills were roughly

analogous and transferable, that is, workshop mechanics from the iron,

machine and building trades; conductors from stagecoach drivers, steamship

stewards and mail boat captains; station masters from commerce and commission

agencies; and clerks from government offices.

In response to the strikes of the 1870s and 1880s, Congress

passed the Arbitration Act of 1888, which authorized the creation of arbitration

panels with the power to investigate the causes of labor disputes and to

issue non-binding arbitration awards. The Act was a complete failure: only

one panel was ever convened under the Act, and that one, in the case of

the 1894 Pullman Strike, issued its report only after the strike had been

crushed by a federal court injunction backed by federal troops.

Congress attempted to correct these shortcomings in the

Erdman Act, passed in 1898. This law likewise provided for voluntary arbitration,

but made any award issued by the panel binding and enforceable in federal

court. It also outlawed discrimination against employees for union activities,

prohibited "yellow dog" contracts (employee agrees not to join a union

while employed), and required both sides to maintain the status quo during

any arbitration proceedings and for three months after an award was issued.

The arbitration procedures were rarely used. A successor statute, the Newlands

Act, was passed in 1913 and proved more effective, but was largely superseded

when the federal government nationalized the railroads in 1917.

As railroads expanded after the Civil War, so too did

the rate of accidents among railroad personnel, especially brakemen. Many

accidents were associated with the coupling and uncoupling of railroad

cars, and the operation of manually operated brakes (hand brakes). The

rise in accidents led to calls for safety legislation, as early as the

1870s. In the 1880s, the number of on-the-job fatalities of railroad workers

was second only to those of coal miners. Through that decade, several state

legislatures enacted safety laws. However, the specific requirements varied

among the states, making implementation difficult for interstate rail carriers,

and Congress passed the Safety Appliance Act in 1893 to provide a uniform

standard. The law required railroads to install air brakes and automatic

couplers on all trains, and led to a sharp drop in accidents.

The Esch–Cummins Act of 1920 terminated the nationalization

program and created a Railway Labor Board (RLB) to regulate wages and issue

non-binding proposals to settle disputes. In 1921 the RLB ordered a twelve

percent reduction in employees' wages, which led to the Great Railroad

Strike of 1922, involving rail shop workers nationwide, followed by a court

injunction to end the strike. Congress passed the Railway Labor Act of

1926 to rectify the shortcomings of the RLB procedures.

Congress added railroad worker safety laws throughout

the 20th century. Significant among this legislation is the Federal Railroad

Safety Act of 1970, which gave the FRA broad resposibilities over all aspects

of rail safety, and expanded the agency's authority to cover all railroads,

both interstate and intrastate.

Impact on American economy and society

According to historian Henry Adams the system of railroads

needed:

the energies of a generation, for it

required all the new machinery to be created--capital, banks, mines, furnaces,

shops, power-houses,

technical knowledge, mechanical population,

together with a steady remodelling of social and political habits, ideas,

and institutions to

fit the new scale and suit the new

conditions. The generation between 1865 and 1895 was already mortgaged

to the railways, and no

one knew it better than the generation

itself.

The impact can be examined through five aspects: shipping,

finance, management, careers, and popular reaction.

Shipping freight and passengers

First they provided a highly efficient network for shipping

freight and passengers across a large national market. The result was a

transforming impact on most sectors of the economy including manufacturing,

retail and wholesale, agriculture and finance. Supplemented with the telegraph

that added rapid communications, the United States now had an integrated

national market practically the size of Europe, with no internal barriers

or tariffs, all supported by a common language, and financial system and

a common legal system. The railroads at first supplemented, then largely

replaced the previous transportation modes of turnpikes and canals, rivers

and intracoastal ocean traffic. For highly efficient Northern railroads

played a major role in winning the Civil War, while the overburdened Southern

lines collapsed in the face of an insurmountable challenge In the late

19th century pipelines were built for the oil trade, and in the 20th century

trucking and aviation emerged.

Basis of the private financial system

Railroads financing provided the basis of the private

(non-governmental) financial system. Construction of railroads was far

more expensive than factories or canals. The famous Erie canal, 300 miles

long in upstate New York, cost $7 million of state money, which was about

what private investors spent on one short railroad in Western Massachusetts.

A new steamboat on the Hudson, Mississippi, Missouri, or Ohio rivers cost

about the same as one mile of track.

In 1860, the combined total of railroad stocks and bonds

was $1.8 billion; 1897 it reached $10.6 billion (compared to a total national

debt of $1.2 billion). Funding came from financiers throughout the Northeast,

and from Europe, especially Britain. The federal government provided no

cash to any other railroads. However it did provide unoccupied free land

to some of the Western railroads, so they could sell it to farmers and

have customers along the route. Some cash came from states, or from local

governments that use money as a leverage to prevent being bypassed by the

main line. Larger sound came from the southern states during the Reconstruction

era, as they try to rebuild their destroyed rail system. Some states such

as Maine and Texas also made land grants to local railroads; the state

total was 49 million acres. The emerging American financial system was

based on railroad bonds. Boston was the first center, but New York by 1860

was the dominant financial market. The British invested heavily in railroads

around the world, but nowhere more so than the United States; The total

came to about $3 billion by 1914. In 1914-1917, they liquidated their American

assets to pay for war supplies.

Inventing modern management

The third dimension was in designing complex managerial

systems that could handle far more complicated simultaneous relationships

than could be dreamed of by the local factory owner who could patrol every

part of his own factory in a matter of hours. Civil engineers became the

senior management of railroads. The leading innovators were the Western

Railroad of Massachusetts and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in the 1840s,

the Erie in the 1850s and the Pennsylvania in the 1860s.

After a serious accident, the Western Railroad of Massachusetts

put in place a system of responsibility for district managers and dispatchers

keep track of all train movement. Discipline was essential—everyone had

to follow the rules exactly to prevent accidents. Decision-making powers

had to be distributed to ensure safety and to juggle the complexity of

numerous trains running in both directions on a single track, keeping to

schedules that could easily be disrupted by weather mechanical breakdowns,

washouts or hitting a wandering cow. As the lines grew longer with more

and more business originating at dozens of different stations, the Baltimore

and Ohio set up more complex system that separated finances from daily

operations. The Erie Railroad, faced with growing competition, had to make

lower bids for freight movement, and had to know on a daily basis how much

each train was costing them. Statistics was the weapon of choice. By the

1860s, the Pennsylvania Railroad—the largest in the world—was making further

advances in using bureaucracy under John Edgar Thomson, president 1852-1874.

He divided the system into several geographical divisions, which each reported

daily to a general superintendent in Philadelphia. All the American railroads

copied each other in the new managerial advances, and by the 1870s emerging

big businesses in the industrial field likewise copied the railroad model.

Career paths

The fourth dimension was in management of the workforce,

both blue-collar workers and white-collar workers. Railroading became a

career in which young men entered at about age 18 to 20, and spent their

entire lives usually with the same line. Young men could start working

on the tracks, become a fireman, and work his way up to engineer. The mechanical

world of the roundhouses have their own career tracks. A typical career

path would see a young man hired at age 18 as a shop laborer, be promoted

to skilled mechanic at age 24, brakeman at 25, freight conductor at 27,

and passenger conductor at age 57. Women were not hired.

White-collar careers paths likewise were delineated. Educated

young men started in clerical or statistical work and moved up to station

agents or bureaucrats at the divisional or central headquarters. At each

level they had more and more knowledge experience and human capital. They

were very hard to replace, and were virtually guaranteed permanent jobs

and provided with insurance and medical care. Hiring, firing and wage rates

were set not by foreman, but by central administrators, in order to minimize

favoritism and personality conflicts. Everything was by the book, and increasingly

complex set of rules told everyone exactly what they should do it every

circumstance, and exactly what their rank and pay would be.[98] Young men

who were first hired in the 1840s and 1850s retired from the same railroad

40 or 50 years later. To discourage them from leaving for another company,

they were promised pensions when they retired. Indeed, the railroads invented

the American pension system.

Love–hate relationship with the railroads

America developed a love–hate relationship with railroads.

Boosters in every city worked feverishly to make sure the railroad came

through, knowing their urban dreams depended upon it. The mechanical size,

scope and efficiency of the railroads made a profound impression; people

would dress in their Sunday best to go down to the terminal to watch the

train come in. David Nye argues that:

The startling introduction of railroads

into this agricultural society provoked a discussion that soon arrived

at the enthusiastic consensus

that railways were sublime and that

they would help to unify, dignified, expand and enrich the nation. They

became part of the public

celebrations of Republicanism. The

rhetoric, the form, and the central figures of civic ceremonies changed

to accommodate the

intrusion of this technology....[Between

1828 and 1869] Americans integrated the railroad into the national economy

and enfolded it

within the sublime.

Travel became much easier, cheaper and more common. Shoppers

from small towns could make day trips to big city stores. Hotels, resorts

and tourist attractions were built to accommodate the demand. The realization

that anyone could buy a ticket for a thousand-mile trip was empowering.

Historians Gary Cross and Rick Szostak argue:

with the freedom to travel came a greater

sense of national identity and a reduction in regional cultural diversity.

Farm children could more

easily acquaint themselves with the

big city, and easterners could readily visit the West. It is hard to imagine

a United States of

continental proportions without the

railroad.

The engineers became model citizens, bringing their can-do

spirit and their systematic work effort to all phases of the economy as

well as local and national government.[ By 1910, major cities were building

magnificent palatial railroad stations, such as the Pennsylvania Station

in New York City, and the Union Station in Washington DC.

But there was also a dark side. As early as the 1830s,

novelists and poets began fretting that the railroads would destroy the

rustic attractions of the American landscape. By the 1840s concerns were

rising about terrible accidents when speeding trains crashed into helpless

wooden carriages. By the 1870s, railroads were vilified by Western farmers

who absorbed the Granger movement theme that monopolistic carriers controlled

too much pricing power, and that the state legislatures had to impose maximum

prices. Local merchants and shippers supported the demand and got some

"Granger Laws" passed. Anti-railroad complaints were loudly repeated in

late 19th century political rhetoric. The idea of establishing a strong

rate fixing federal body was achieved during the Progressive Era, primarily

by a coalition of shipping interests. Railroad historians mark the Hepburn

Act of 1906 that gave the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) the power

to set maximum railroad rates as a damaging blow to the long-term profitability

and growth of railroads. After 1910 the lines faced an emerging trucking

industry to compete with for freight, and automobiles and buses to compete

for passenger service.

Historiography

There is no question about the importance of railroads

in American history. Churella finds that back in the 1950s business and

economic historians, led by Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. and Robert Fogel, made

railroads the centerpiece of advanced historiography.[110] That era has

passed as graduate programs have faded away, courses on railroad history

do not make the curriculum, and the historiography has shifted away from

professional historian to the "rail fans"—very well informed amateur writers

fascinated by the memorabilia, technology and locomotives of the steam

era. Looking at the voluminous output of rail fan authors, Klein says:

The vast bulk of this work is devoted

to minute descriptions of power, rolling stock, obscure short lines, and

technical subjects.... But few address the larger questions of railroad

history or place their topic in broader contexts.

The result is a multiplicity of histories of specific

railroads, large and small. Typically they deal with standard topics: the

builders and their organizational, legislative and financial dealings;

colorful construction crews laying down wood ties and steel rail; the development

of locomotives and passenger cars; boosters who sought a stop in their

little town else it would die; the 1880–1920 golden age of the passenger

long-distance travel and local excursions; the steady erosion of passenger

service during the automobile age; the freight agent and the small-town

depot. They end with the more recent saga of retrenchment, merger, and

abandonment. Klein, Churella, Roth, and Franham all find that the popular

writers show little interest in the development of managerial and organizational

complexity of the sort that Chandler studied, or the economic impact that

concerned Fogel's cohort. From outside the field of railroad history, academic

labor historians now deal with the culture of the workers, strikes, the

careers for blue collar and white collar men, and racial discrimination.

Academic political historians deal with the Granger, Populist and Progressive

attacks, and in federal or state regulation.

Ralroad Mileage

1830 = 40

1840 = 2,755

1850 = 8,571

1860 = 28,920

1870 = 49,168

1880 = 87,801

1890 = 163,562

|