| I was looking in to gangs of the old west. What I found

was a list that gave the names and the years they operated. What jumped

out at me as interesting was the average life of a gang was less than 5

years. Most one or two. A hand full maybe seven or eight years.

Examples:

The Wild Bunch 1892-1895

Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch 1899-1902

Reno Gang 1866-1868

Dalton Gang 1890-1892

Soap Gang 1880-1898 (19 years ??) I have never

heard of this group.

I am going to see what I can find on some of these gangs.

Hope it makes for good reading.

Let's start with the Soap Gang......

|

| Soap Gang (1880-1902) - from Wikipedia

Soapy Smith

| Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith II (November 2, 1860

– July 8, 1898) was a con artist, saloon and gambling house proprietor,

gangster, and crime boss of the 19th-century Old West. His most famous

scam, the prize package soap sell racket, presented him with the sobriquet

of "Soapy", which remained with him to his death.

Although he traveled and operated his confidence swindles

all across the western United States, he is most famous for having a major

hand in the organized criminal operations of Denver and Creede, Colorado,

and Skagway, Alaska, from 1879 to 1898. In Denver, he ran several saloons,

gambling halls, cigar stores, and auction houses that specialized in cheating

their clientele. In Denver, Soapy began to make a name for himself across

the country as a bad man. Denver is also where he entered into the arena

of political fixing, where, for favors, he could sway the outcome of city,

county, and state elections.

He used the same methods of operation when he settled

in the towns of Creede and Skagway, opening businesses with the primary

goal of gently robbing his customers, while making a name for himself.

He died in spectacular fashion in the shootout on Juneau Wharf in Skagway.

Early years

Jefferson Smith was born in Coweta County, Georgia, to

a family of education and wealth. His grandfather was |

Soapy smith 1890 |

a plantation owner and a popular Georgia senator and legislator.

His father was an attorney. The family met with financial ruin at the close

of the American Civil War. In 1876, they moved to Round Rock, Texas, to

start anew. In Round Rock, Jefferson began his career as a confidence man.

Smith left his home shortly after the death of his mother

in 1877, but not before witnessing the shooting of the outlaw Sam Bass.

In Fort Worth, Smith formed a close-knit, disciplined gang of shills and

thieves to work for him. Soon, he became a well-known crime boss, the "king

of the frontier con men".

Career

Smith spent the next 22 years as a professional bunko

man and boss of an infamous gang of loyal swindlers, known as the Soap

Gang, which included famous men such as Texas Jack Vermillion and "Big

Ed" Burns. The gang moved from town to town, plying their trade on their

unwary victims. Their principal method of separating victims from their

cash was the use of "short cons", swindles that were quick and needed little

setup and few helpers. The short cons included the shell game, three-card

monte, and rigged poker games, which they called "big mitt".

The prize package soap racket

Some time in the late 1870s or early 1880s, Smith began

cheating crowds with a ploy the Denver newspapers dubbed "The prize soap

racket".

Smith would open his "tripe and keister" (display case

on a tripod) on a busy street corner. Piling ordinary soap cakes onto the

keister top, he began expounding on their wonders. As he spoke to the growing

crowd of curious onlookers, he would pull out his wallet and begin wrapping

paper money, ranging from one dollar up to one hundred dollars, around

a select few of the bars. He then finished each bar by wrapping plain paper

around it to hide the money.

He appeared to mix the money-wrapped packages in with

wrapped bars containing no money, and then sold the soap to the crowd for

one dollar a cake. A shill planted in the crowd would buy a bar, tear it

open, and loudly proclaim that he had won some money, waving it around

for all to see. This performance had the desired effect of enticing the

sale of more packages. More often than not, victims bought several bars

before the sale was completed. Midway through the sale, Smith would announce

that the hundred-dollar bill yet remained in the pile, unpurchased. He

then would auction off the remaining soap bars to the highest bidders.

Through manipulation and sleight-of-hand, he hid the cakes

of soap wrapped with money and replaced them with packages holding no cash.

The only money "won" went to shills, members of the gang planted in the

crowd pretending to win, in order to increase sales.

On one occasion, Smith was arrested by policeman John

Holland for running his soap-sell racket. While writing in the police log

book, Holland had forgotten Smith's first name and wrote "Soapy". The sobriquet

stuck, and he became known as "Soapy Smith" all across the western United

States. He used this swindle for 20 years with great success. The soap

sell, along with other scams, helped finance Soapy's criminal operations

by paying graft to police, judges, and politicians. He was able to build

three major criminal empires: the first in Denver (1886–1895); the second

in Creede, Colorado (1892); and the third in Skagway, Alaska (1897–1898).

Criminal boss of Denver

In 1879, Smith arrived in Denver for the first time. By

1882, he had successfully built the first of his empires. Con men normally

moved around to keep out of jail, but as Smith's power and gang grew, so

did his influence at city hall, allowing him to remain in the city, protected

from prosecution. By 1887, he was reputedly involved with most of the criminal

bunko activities in the city. Newspapers in Denver reported that he controlled

the city's criminals and underworld gambling, and accused corrupt politicians

and the police chief of receiving graft from him.

Tivoli Club

In 1888, Soapy opened the Tivoli Club, on the southeast

corner of Market and 17th Streets, a combination saloon and gambling house.

Legend has it that above the entrance of the stairway leading upstairs

to the gambling games was a sign that read caveat emptor, Latin for "let

the buyer beware". Soapy's younger brother, Bascomb Smith, joined the gang

and operated a cigar store that was a front for dishonest poker games and

other swindles, operating in one of the back rooms. Other operations included

fraudulent lottery shops, a "sure-thing" stock exchange, fake watch and

bogus diamond auctions, and the sale of stocks in nonexistent businesses.

Politics and other cons

Because of bribes, some of the police officers patrolling

the streets would not arrest Soapy or members of his gang. Other officers

feared Soapy's quick and violent anger. Occasionally, Soapy or one of his

men would be arrested. Friends, attorneys, and associates were always ready

to obtain their quick release from jail. A voting fraud trial after the

municipal elections of 1889 focused attention on corrupt ties and payoffs

between Soapy, the mayor, and the chief of police—a combination referred

to in local newspapers as "the firm of Londoner, Farley and Smith." The

mayor lost his job, but Soapy remained untouched.

Smith opened an office in the prominent Chever block,

one block south of his Tivoli Club, from which he ran his many operations.

This also fronted as a business tycoon's office for high-end swindles.

Soapy was not without enemies and rivals for his position

as the underworld boss. He faced several attempts on his life and shot

several of his assailants. He became known increasingly for his gambling

and bad temper.

Creede, Colorado

In 1892, with Denver in the midst of antigambling and

saloon reforms, Smith sold the Tivoli and moved to Creede, a mining boomtown

that had formed around a major silver strike. Using Denver-based prostitutes

to cozy up to property owners and convince them to sign over leases, he

acquired numerous lots along Creede's main street, renting them to his

associates. After gaining enough allies, he announced that he was the camp

boss.

With brother-in-law and gang member William Sidney "Cap"

Light as deputy sheriff, Soapy began his second empire, opening a gambling

hall and saloon called the Orleans Club. He purchased and briefly exhibited

a petrified man nicknamed "McGinty" for an admission of 10 cents. While

customers were waiting in line to pay their dime, Soapy's shell and three-card

monte games were winning dollars out of their pockets.

Smith provided an order of sorts, protecting his friends

and associates from the town's council and expelling violent troublemakers.

Many of the influential newcomers were sent to meet him. Soapy grew rich

in the process, but again was known to give money away freely, using it

to build churches, help the poor, and to bury unfortunate prostitutes.

Creede's boom very quickly waned and corrupt Denver officials

sent word that the reforms there were coming to an end. Soapy took McGinty

back to Denver. He left at the right time, as Creede soon lost most of

its business district in a huge fire on 5 June 1892. Among the buildings

lost was the Orleans Club.

Back to Denver

On his return to Denver, Smith opened new businesses that

were nothing more than fronts for his many short cons. One of these sold

discounted railroad tickets to various destinations. Potential purchasers

were told that the ticket agent was out of the office, but would soon return,

and then offered an even bigger discount by playing any of several rigged

games. Soapy's power grew to the point that he admitted to the press that

he was a con man and saw nothing wrong with it. In 1896, he told a newspaper

reporter, "I consider bunco steering more honorable than the life led by

the average politician."

Colorado's new governor, Davis Hanson Waite, elected on

a Populist Party reform platform, fired three Denver officials he felt

were not abiding by his new mandates. They refused to leave their positions

and were quickly joined by others who felt their jobs were threatened.

The governor called out the state militia to assist removing those fortified

in city hall. The military brought with them two cannons and two Gatling

guns. Soapy joined the corrupt officeholders and police at the hall and

found himself commissioned as a deputy sheriff. He and several of his men

climbed to the top of the city hall's central tower with rifles and dynamite

to fend off any attackers. Cooler heads prevailed, however, and the struggle

over corruption was fought in the courts, not on the streets. Soapy Smith

was an important witness in court.

Governor Waite agreed to withdraw the militia and allow

the Colorado Supreme Court to decide the case. The court ruled that the

governor had authority to replace the commissioners, but he was reprimanded

for bringing in the militia, in what became known as the "City Hall War".

Waite ordered the closure of all Denver's gambling dens,

saloons, and bordellos. Soapy exploited the situation, using the recently

acquired deputy sheriff's commissions to make fake arrests in his own gambling

houses, apprehending patrons who had lost large sums in rigged poker games.

The victims were happy to leave when the "officers" allowed them to walk

away from the crime scene rather than be arrested, naturally without recouping

their losses.

Eventually, Soapy and his brother Bascomb Smith became

too well known, and even the most corrupt city officials could no longer

protect them. Their influence and Denver-based empire began to crumble.

When they were charged with attempted murder for the beating of a saloon

manager, Bascomb was jailed, but Soapy managed to escape, becoming a wanted

man in Colorado. Lou Blonger and his brother Sam, rivals of the Soap Gang,

acquired his former control of Denver's criminals.

Before leaving, Soapy tried to perform a swindle started

in Mexico, where he tried to convince President Porfirio Diaz that his

country needed the services of a foreign legion made up of American toughs.

Soapy became known as Colonel Smith, and managed to organize a recruiting

office before the deal failed.

Skagway and the Klondike gold rush

| When the Klondike Gold Rush began in 1897, Soapy moved

his operations to Dyea and Skagway, Alaska (then spelled Skaguay). His

first attempt at occupying Skaguay ended in failure when miners' committees

encouraged him to leave the area after operating his three-card monte and

pea-and-shell games on the White Pass Trail for less than a month. He traveled

to St. Louis and Washington, DC, and did not return to Skagway until late

January 1898.

Soapy set up his third empire much the same way as he

had in Denver and Creede. He put the town's deputy U.S. marshal on his

payroll and began collecting allies for a takeover. Soapy opened a fake

telegraph office in which the wires went only as far as the wall. Not only

did the telegraph office obtain fees for "sending" |

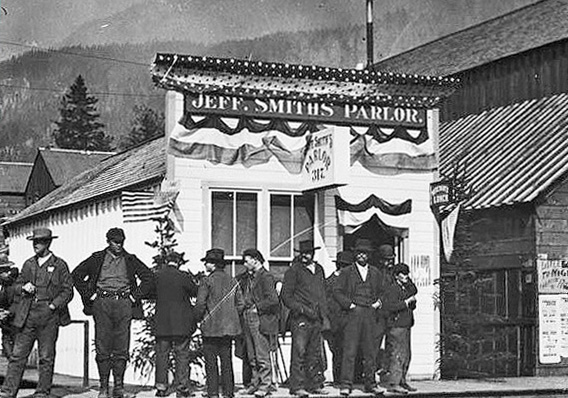

Jeff. Smith's Parlor,

Soapy's base of operations

1898 |

.

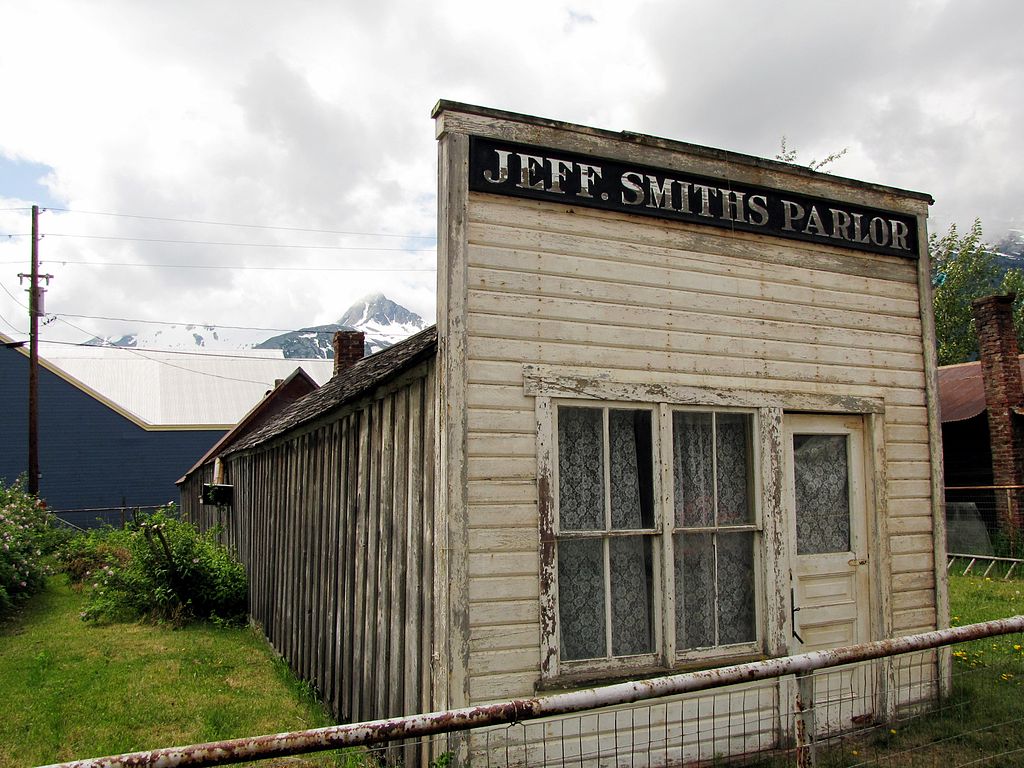

.

2009 before restoration |

messages, but also cash-laden victims soon found themselves

losing even more money in poker games with newfound "friends". Telegraph

lines did not reach or leave Skagway until 1901. Soapy opened a saloon

named Jeff Smith's Parlor in March 1898 as an office from which to run

his operations. Although Skagway already had a municipal building, Soapy's

saloon became known as "the real city hall". Skagway was gaining a reputation

as a "hell on earth", with many perils for the unwary.

Smith's men played a variety of roles, such as newspaper

reporter or clergyman, with the intention of befriending a new arrival

and determining the best way to rid him of his money. The new arrival would

be steered by his "friends" to dishonest shipping companies, hotels, or

gambling dens, until he was wiped out. If the man was likely to make trouble

or could not be recruited into the gang, Soapy himself would then appear

and offer to pay his way back to civilization.

When a vigilance committee, the "Committee of 101", threatened

to expel Soapy and his gang, he formed his own "law and order society",

which claimed 317 members, to force the vigilantes into submission. Most

of the petty gamblers and con men did indeed leave Skagway at this time,

and Smith resorted to other means to appear respectable to the community.

During the Spanish–American War in 1898, Smith formed

his own volunteer army with the approval of the U.S. War Department, known

as the "Skaguay Military Company", with Soapy as its captain. Smith wrote

to President William McKinley and gained official recognition for his company,

which he used to strengthen his control of the town.

On July 4, 1898, Soapy rode as marshal of the Fourth Division

of the parade leading his army on his gray horse. On the grandstand, he

sat beside the territorial governor and other officials.

Death

On July 7, 1898, John Douglas Stewart, a returning Klondike

miner, came to Skagway with a sack of gold valued at $2,700 ($78,870 in

2013 dollars.) Three gang members convinced the miner to participate in

a game of three-card monte. When Stewart balked at having to pay his losses,

the three men grabbed the sack and ran. The "Committee of 101" demanded

that Soapy return the gold, but he refused, claiming that Stewart had lost

it "fairly".

On the evening of July 8, the vigilance committee organized

a meeting on the Juneau wharf. With a Winchester rifle draped over his

shoulder, Soapy began an argument with Frank H. Reid, one of four guards

blocking his way to the wharf. A gunfight, known as the Shootout on Juneau

Wharf began unexpectedly, and both men were fatally wounded.

Soapy's last words were "My God, don't shoot!" A letter

from Sam Steele, the legendary head of the Canadian Mounties at the time,

indicates that another guard, Jesse Murphy, may have fired the fatal shot.

Soapy died on the spot with a bullet to the heart. He also received a bullet

in his left leg and a severe wound on the left arm by the elbow. Reid died

12 days later with a bullet in his leg and groin area. The three gang members

who robbed Stewart received jail sentences.

Soapy Smith was buried several yards outside the city

cemetery. Due to the way Smith's legend has grown, every year on July 8,

wakes are held around the United States in Soapy's honor. His grave and

saloon are on most tour itineraries of Skagway.

Soapy Smith's fame

Smith’s fame began in 1889 in Denver when he assaulted

editor John Arkins of the Denver Rocky Mountain News. The newspaper declared

war on Smith and the Soap Gang, sending articles and warnings about the

bunco gang all across the U.S. Smith's fame continued to grow right up

to and beyond the day he died. The story told in the Skaguay News on July

9, 1898, and newspapers throughout the country was that one brave man had

sacrificed himself to slay a vicious con man – the con king of Skagway

– so Skagway could be freed of all crime.

By 1907, ten years after the founding of Skagway, aspiring

politician Chris Shea authored a booklet using photographs taken by Sinclair

and professional Skagway photographers Theodore Peiser and Case and Draper.

He called it, after a collage of photographs, "The Soapy Smith Tragedy".

This booklet was the first book published on Smith.

By the 1950s, Smith had become sort of a Robin Hood figure,

who took from the miners and gave to the poor widows, orphans, dogs, and

criminals who lived by their wits. Smith, the antihero, was a loyal friend

who stood by his men, outwitted stuffy reformers and conventional citizens,

and lives on as the rascally King of the Con Men.

|

Banditti of the Prairie (1835-1859) - from Wikipedia

| The Banditti of the Prairie, also known as "The Banditti",

"Prairie Pirates", "Prairie Bandits", and "Pirates of the Prairie", in

the U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and the territory of Iowa,

were a group of loose-knit, outlaw gangs, during the early-mid-19th century

(1800s). Though bands of roving criminals were common in many parts of

Illinois, the counties of Lee, DeKalb, Ogle, and Winnebago were especially

affected by them. In the year 1841, the escalating pattern of house burglary,

horse and cattle theft, stagecoach and highway robbery, counterfeiting,

and murder associated with the Banditti had come to a head in Ogle County.

As the crimes continued, local citizens formed bands of vigilantes known

as Regulators. A clash between the Banditti and the Regulators in Ogle

County near Oregon, Illinois, resulted in the outlaws' demise and decreased

Banditti activity and violent crime within the county.

Banditti and Regulator activity continued well after the

lynching that took place in 1841. Crimes continued, committed by both sides,

across northern/central Illinois. The Banditti were involved in other notable

events as well, including the 1845 torture-murder of merchant Colonel George

Davenport, the namesake of Davenport, Iowa. Edward Bonney, an amateur detective

who hunted down and brought to justice the killers, wrote of his exploits

and alibi, which were recounted in his book, Banditti of the Prairies,

or the Murderer's Doom!!: A Tale of the Mississippi Valley, published in

Chicago in 1850. The outlaw gangs also continued to be active in Lee and

Winnebago counties following the events in Oregon.

The Banditti in Illinois

Northern Illinois activity

The "Prairie Bandits" were active, across northern Illinois,

especially in Lee, Ogle, Winnebago, and DeKalb counties, from 1835, until

the events leading to their ultimate demise began on March 21, 1841. The

Bandits wielded considerable influence in the area, collectively known

as the Rock River Valley, following the influx of immigrants, after the

Black Hawk War of 1832, the last Indian war in Illinois.

The Banditti posed a far greater threat, for a much longer period, than

the exaggerated paranoia of the two month, Native American conflict. Former

Illinois Governor Thomas Ford wrote in History of Illinois: |

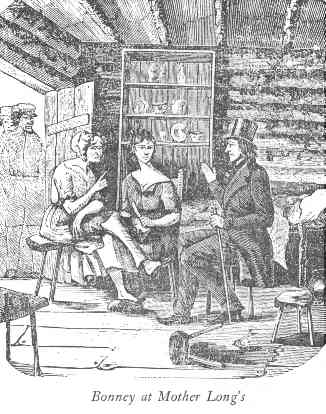

A woodcut of Edward Bonney, the bounty

hunter and amateur detective, who, in 1845,

posed as a counterfeiter, ironically had been

arrested, for counterfeiting, himself, a few

years earlier, to infiltrate, a faction, of the

"Banditti of the Prairie" and track down the

infamous murderers of Colonel George

Davenport, who wrote the 1850 book,

The Banditti of the Prairies: or, The

murderer's doom, a tale of

Mississippi Valley and the Far West. |

“ .. the northern part of the State was not destitute

of its organized bands of rogues engaged in murders, robberies, horsestealing,

and in making and passing counterfeit money. These rogues were scattered

all over the north: but the most of them were located in the counties of

Ogle, Winnebago, Lee and DeKalb. In the county of Ogle they were so numerous,

strong, and organized that they could not be convicted for their crimes.

”

Banditti crimes in Lee and Ogle Counties

In Lee County, Illinois, the Banditti also, had enough

power to get away, unnoticed. The group had enough allies that they were

scattered throughout the county. The connections the Banditti had around

the county made illegal activities such as counterfeiting and dealing in

and concealing stolen property easy to perpetrate. It was reported, that,

at one time, every township officer, in Lee County, was a member of the

Banditti. Acts of theft were carried on in defiance of authority. Citizens

were threatened when they tried to seek redress from the thieves.

In the end, the Prairie Bandits' activity in Ogle and

Lee County became more than area residents were willing to withstand. In

Ogle County the crimes that occurred in March 1841 resulted in a kangaroo

court which culminated with the lynching of two Banditti near Oregon, Illinois.[4]

In nearby Lee County, a Vigilance Committee was formed by men from throughout

Lee County, and especially Lee Center Township took an active role in suppressing

the Banditti activity.

Beginning with the events on March 21, 1841, violence

and retribution escalated in, the area around the Ogle County seat, of

Oregon. Illinois, still frontier in 1841, was settled by large numbers

of migrants after the Black Hawk War. The settlers were followed to the

area by a criminal element. The Banditti of the Prairie were part of the

crime problem that plagued much of northern Illinois. As such, the concerned

citizens of Ogle County, organized and eventually took the law into their

own hands.

Ogle County Banditti activity

On March 21, 1841, six members of the Banditti were arrested

on charges of counterfeiting. They were held at the Ogle County Jail in

the city of Oregon. That night a fire broke out in the newly completed

courthouse, which was to be used for the first time the next day.[4] The

fire, set by the Banditti, was meant as a diversion to facilitate the escape

of the apprehended gang members. The diversion failed; though the courthouse

burned to the ground, the jail remained intact. The court records concerning

the case had been safely concealed in the home of the court clerk. Ford,

who sat as Ogle County Circuit Judge at the time, reconvened court at a

new location and the trial for the accused counterfeiters went on as planned.

Arrests and county court trial of Banditti

The jury, as was common in Ogle County at the time, had

been infiltrated by one of the Banditti, who subsequently refused to convict

the accused. The other jurors persuaded the rogue juror to convict by threatening

to lynch him in the jury room if he failed to agree with the majority opinion.

The Banditti juror capitulated and three of the accused were convicted.

The convicts, however, soon escaped and avoided their sentences.

Formation of the Regulators

In April, 1841, the community of Oregon and Ogle County

in general had reached a boiling point. During that month, a group of citizens,

possibly acting under direct counsel from Ford, met at a schoolhouse in

White Rock Township and formed an organization aimed at driving the outlaws

out of the county. Membership in the new group grew quickly, soon numbering

in the hundreds, and copycat chapters sprang up all over the Rock River

Valley. These bands of citizen vigilantes were most often known as "Regulators".

Other names included, "lynching clubs", and in Lee County one group was

known as the "Associations for the Furtherance of the Cause of Justice".

The Regulators in Ogle County began by whipping two horse

thieves, one of whom joined the group after the incident. The first Ogle

County Regulator captain, W.S. Wellington, stepped aside, after his grist

mill was destroyed and his horse tortured and killed in April 1841. The

new captain, John Campbell, was a resident of White Rock Township. The

local Banditti were the Driscoll family and members of the Driscoll Gang.

At the head was John Driscoll, who had migrated from Ohio in 1835 with

his four grown sons, William, David, Pierce and Taylor. The Driscoll's

lived on Killbuck Creek in northeast Ogle County. Driscoll and his son

Taylor had both been convicted of arson while they lived in Ohio.

Campbell's ascension to the lead Regulator post was met

with hostiity from the Driscoll camp. William Driscoll immediately sent

Campbell a letter offering to kill him. Campbell responded in kind; he

assembled 200 Regulators, and marched to the Driscoll home. A small group

of Banditti had gathered at the Driscoll homestead but seeing they were

outnumbered they fled, only to return with the DeKalb County Sheriff and

other authorities in tow. The Sheriff and his companions did not see the

events as the outlaws had hoped; they sided with the vigilantes, and the

Driscolls promised to leave within twenty days Instead of leaving, the

Driscolls and the other Banditti held a meeting in which they determined

that Campbell and his fellow Regulator, Phineas Chaney, had to be murdered.

Regulator trial and execution of Banditti by firing

squad

| Nearly three months later, on June 25, 1841, there was

an attempt to kill Chaney. Two days passed, and on June 27 David Driscoll

and his brother Taylor attacked Campbell at his farm. David fired the single,

fatal shot. Campbell's son, Martin, then 13, fired at the Driscolls with

a shotgun, but the weapon failed to go off.

The account that stated David and Taylor Driscoll were

the gunmen came from Campbell's wife. Despite this claim, hoofprints at

the scene of the crime indicated that there had been an additional three

horses there. It was these hoofprints that the Regulators followed back

to the Driscoll home. Once there, accompanied by Ogle County Sheriff William

T. Ward, the angry group confronted John Driscoll. After questioning by

Ward and his accompanying mob, the sheriff was satisfied that John Driscoll

was involved in Campbell's murder and arrested him "on suspicion of being

accessory to the murder". While David and Taylor Driscoll, the gunmen,

fled that fateful day, William and Pierce Driscoll were arrested by a group

of Regulators from Rockford.

The regulator court was convened at "Stephenson's Mill"

in Washington Grove, Illinois, because of the courthouse fire in March,

1841. The court was organized, witnesses gathered, and proceedings went

forward. A crowd gathered at the mill, estimated to be as many as 500.

At this point, Ogle County Sheriff Ward appealed to have the Driscolls

returned to his custody. E.S. Leland presided over the makeshift court

as judge, a |

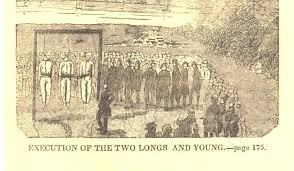

The October, 1845 hangings of, Granville Young and

John and Aaron Long, Banditti murderers, of Colonel

George Davenport, from the 1850 book, The Banditti

of the Prairies, Or, The Murderer's Doom!!:

A Tale of the Mississippi Valley by Edward Bonney,

who is standing to the right, of the gallows, wearing

a top hat and black suit. |

position he would later hold legitimately in Ottawa, Illinois.

Leland directed those present who were Regulators to form a circle, 120

men initially stepped forward; nine were dismissed as not being "real"

Regulators. The 111 men remaining formed the "jury".

On June 29, 1841, the vigilante trial began and William

Driscoll admitted to telling his brother to kill Campbell, but only "in

jest". His father, John, denied vehemently that he had anything to do with

the murder, though he did admit to stealing numerous horses. Pierce Driscoll

was released from custody when no evidence was found linking him to the

crime. At the trial's end the guilty verdict was described as "almost unanimous";

the Driscolls were immediately sentenced to be hanged on the spot. The

Driscolls refused to be hanged and instead requested that they be shot.

Before the execution was carried out, William Driscoll confessed to six

murders; John confessed to nothing. The Regulators then assembled a large

firing squad and prepared to carry out the execution. The Regulators divided

themselves into two separate squads, one for each man, of 55 and 56 riflemen.

The line of 56 executioners shot first John Driscoll. William, by this

time trembling, was gunned down next by the line of 55 Regulators.

The description in the 1909 Historical Encyclopedia of

Illinois was somewhat more tame:

“ [the Driscolls were] . . . led out, and shot,

and then the other was led out, and after being shown the body of his dead

relative, he was exhorted to confess that he had committed the crime charged

against him. This he refused to do, but acknowledged that he had committed

other crimes for which he deserved death.”

The lynching of the Driscolls did not spell the end of

the Regulators, nor the Banditti, but it did serve to greatly decrease

Banditti activity in Ogle County.

Winnebago County Banditti activity

Though the banditti continued to plague areas of northern

Illinois, they were largely eradicated from Ogle County, following the

lynching of the Driscolls. However, both the Banditti and the Regulators

continued to be active. In Winnebago County, in early July 1841, the offices

of the Rock River Express were ransacked, an early predecessor to the Rockford

Register Star, the daily newspaper of Rockford, Illinois. The offices were

likely trashed in response to a scathing editorial published by the Express

speaking out against the vigilante action taken by the Regulators.

Murder of Colonel Davenport by Banditti in Rock Island

Banditti crimes continued well into the 1840s. One of

the most shocking incidents, outside of the murderous crimes of the Driscoll

Gang, in Oregon, to be attributed to the Banditti, was the callous murder

of Colonel George Davenport at his home on the grounds of Rock Island Arsenal.

On July 4, 1845, Colonel Davenport was assaulted in his home by Banditti

men who thought he had a fortune in his safe. Beaten and left for dead,

he survived long enough to give a full description of the criminals, before

he died that night. An amateur detective named Edward Bonney tracked down

the killers and brought them to justice. Five men were charged with the

murder of George Davenport, and all but one, who escaped before the trial,

were hung for the murder. Three more men were charged with accessories

to the murder. One man was sentenced to life in prison, but escaped and

was killed three months later, one man served one year in prison, and the

charges were dropped against the third man, who left the area.

Lee County Banditti activity

In Lee County, Illinois the Banditti were most active

in the years 1843-1850, after the lynching in Oregon. During that period,

crime and gang operations were rampant throughout the Mississippi Valley

but Lee County, like its neighboring northern Illinois counties, saw consistent

activity. Near the Lee County village of Franklin Grove, a brutal double-murder

was committed in 1848. On May 20, 1848, area resident Joshua Wingert, while

searching through the grove two miles (3 km) west of town for his cattle,

came upon a small log hut. Inside he discovered the bodies of two men,

killed with their own axe. One of the men was nearly decapitated and the

other had a large gash across his forehead. The assumed motive was robbery,

as the hut was ransacked and bloody fingerprints were all about the small

building. The Banditti perpetrator or perpetrators were never apprehended.

Also, in Lee County, the Banditti were active in and around

Inlet Grove. In June 1844 the group carried out a daring robbery of a Mr.

Haskell. Haskell's residence was robbed by masked men in the midst of a

summer thunderstorm. The perpetrators entered Haskell's bedroom while he

and his wife were asleep. The robbers dragged a trunk of money out from

underneath the sleeping Haskell's bed undetected, much of the noise they

made probably drowned out by thunder. The Haskells did not discover they

had been the victims of a robbery until the next morning.

|

| Jack Taylor Gang (1884-1887) from Wikipedia

he Jack Taylor Gang (ca. 1884 to 1887) was an outlaw

gang of the Old West which operated mostly in Arizona Territory and Mexico.

The gang was first organized by Jack Taylor, a minor outlaw

with moderate skills in train robbery. This brought the gang to the attention

of later famed Railroad Detective Jeff Milton, and Cochise County, Arizona

Sheriff John Slaughter, under whom Milton was at that time working as a

Deputy Sheriff. The gang built a reputation for being particularly cruel,

and quick to shoot when confronted, and were wanted mainly for the murder

of a train engineer in Sonora, and another train robbery in which they

killed four passengers. In 1887, Sheriff Slaughter received information

that several members of the gang were hiding out at the rural home of Flora

Cardenas. However, by the time Slaughter and his posse had reached her

house, the gang members, identified as Geronimo Miranda, Manuel Robles,

Nieves Deron and Fred Federico, had fled.

Sheriff Slaughter and Jeff Milton tracked them to Contention

City, Arizona, to the home of wood cutter Guadeloupe Robles, brother to

Manuel Robles. Gang members Nieves Deron and Manuel Robles were hiding

there, and without warning Sheriff Slaughter, Milton, and his deputies

stormed the house. Guadeloupe Robles was shot dead by Slaughter, while

Nieves Deron opened fire on Slaughter and his posse, with one bullet grazing

Slaughter's ear lobe. The two gang members fled toward the rocks near the

house, exchanging fire with the posse as they ran. Slaughter and two of

his deputies shot and killed Deron, and shot and wounded Manuel Robles,

who, though wounded, escaped into a thicket. During that same month, gang

leader Jack Taylor was captured in Mexico by the Mexican Rurales, and sentenced

to life in prison.

The remaining members of the gang, Manuel Robles, Geronimo

Miranda and Fred Federico, were still at large. Robles had yet to fully

recover from his gunshot wounds suffered in Contention City, and this was

being hindered by his having to remain constantly on the move. Robles and

Miranda were shot and killed during a gun battle with the Mexican Rurales

in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains later in 1887. On August 12, 1888,

gang member Fred Federico mistook Deputy Sheriff Cesario Lucero for Sheriff

Slaughter, in a planned ambush. Federico shot and killed Deputy Lucero,

and was captured shortly thereafter. He was hanged, and was the last of

the Jack Taylor Gang.

|

Augustine Chacon Gang (1890-1902) from Wikipedia

| Augustine Chacon (1861 – November 21, 1902), or El Peludo

(English: "The Hairy One"), was a Mexican outlaw and folk hero of Arizona

Territory. Although a self-proclaimed badman, he was well liked by settlers,

who treated him as a Robin Hood-like character, rather than a typical raider.

According to Old West historian Marshall Trimble, Chacon was "one of the

last of the hard-riding desperados who rode the owl-hoot trail in Arizona

around the turn of the century." He was considered extremely dangerous

to authorities, having killed about thirty people before being captured

by Burton C. Mossman and hanged.

Biography

Early life

Chacon was born in 1861 in the northwestern Mexican state

of Sonora, which was a sparsely populated wilderness at the time. He is

first recorded in history as being a peace officer in the town of Sierra

del Tigre, though he also found work hauling wood and ore at some point.

In 1888 or 1889, Chacon moved across the international border to Morenci,

where he became known as an "excellent cowboy throughout the Arizona Territory."

However, in 1890, he had a disagreement with his employer, a rancher named

Ben Ollney, about three months' worth of pay. For some reason, Ben refused

to pay Chacon his wages so the two "exchanged heated words" before the

latter rode off towards Safford in disgust. After spending the night drinking,

Chacon armed himself and then returned to the ranch on the next day with

the intention of collecting his money. Once again, Ben refused to pay,

but he went even further by insulting Chacon and |

Augustine Chacon |

laughing at him. No doubt a few more heated words followed,

at the end of which, Ben attempted to draw his pistol, but Chacon drew

first and shot his antagonist dead. Five cowboys rushed to the scene to

avenge their slain employer, but Chacon held his ground and shot all of

them. Four of them died, but the fifth escaped to Whitlock Springs, where

he raised the alarm. Ben Ollney's brother lived at Whitlock Springs and

he quickly organized a posse of six men to go after Chacon, who by that

time was fleeing south towards the border. The posse followed Chacon's

trail to a box canyon, cornered him in and then called out for his surrender,

but, the day-old outlaw decided he wasn't going to. Chacon then equipped

himself with two revolvers and charged his pursuers on horseback. Four

more cowboys were killed and Chacon rode off with a slight wound to one

of his arms.

According to author R. Michael Wilson, the entire Ollney

family was killed in Whitlock Springs two days later, but Chacon claimed

he was at a Mexican woodcutter's camp when the murders occurred, tending

to his wound and accompanied by a pair of Arizona train robbers, Burt Alvord

and Billy Stiles. Several months passed before Chacon was found back in

Arizona. He was arrested near Fort Apache while visiting a girl and the

next day a lynch mob formed to carry out an illegal hanging. However, when

the mob made it to the jail all they found was an empty cell, Chacon having

cut the window's metal bars with a hacksaw and slipped out. Some locals

claimed that Ben Ollney's daughter, Nelly, delivered Chacon the saw because

she didn't believe he had killed her father.

Chacon Gang

| Over the next few years, Chacon led a gang which operated

primarily as horse thieves and cattle rustlers. They lived in the Sierra

Madre of Sonora but routinely crossed into Arizona to commit crimes and

sell off stolen property. The author of Famous sheriffs & western outlaws,

William MacLeod Raine, says that Chacon's band was the "worst gang of outlaws

that ever infested the border." Multiple murders, rapes, robberies and

other crimes were attributed to the gang, but they always seemed to escape

capture. Many notable lawmen became involved in the pursuit of Chacon and

his bandits, among them John Horton Slaughter, a sheriff and veteran gunfighter.

One time at Tombstone, Chacon was caught bragging that he would kill Slaughter

on sight so when the sheriff learnt of this he did a little investigating

and was told by an informant where Chacon was held up. Later that night,

Slaughter and his then deputy, Burt Alvord, surrounded the canvas tent

Chacon was sleeping in, but when they called on him to surrender, the bandit

jumped up and started running out the back entrance. Slaughter fired once

with his shotgun and he assumed he hit Chacon, since he went tumbling into

a ditch next to where the tent was placed. But when the lawmen got down

to the bottom, they found no body and decided Chacon must have tripped

on a rope at the foot of the tent and the shotgun blast passed over his

head. In late 1894, two employees of the Detroit Copper Company were hunting

along Eagle Creek, Arizona when they were murdered by a band of outlaws.

The Chacon gang often slaughtered stolen cattle in the area, and the people

of Morenci decided the bandit chief was responsible. Not long after that,

the body of an old miner was found concealed in an abandoned mine shaft

and again Chacon was blamed.

Chacon and his men also robbed a casino in Jerome, killing

four people in the process, and then they held up a stagecoach outside

Phoenix. Furthermore, a group of sheep-shearers were found dead at their

camp around this time and, as usual, Chacon was said to have been responsible.

Gunfight at Morenci

The most famous gunfight involving the Chacon gang occurred

in 1895, after they robbed a general store in Morenci. On the night of

December 18, Chacon and two of his followers, Pilar Franco and Leonardo

Morales, entered McCormack's store, which was managed by a man named Paul

Becker. After stabbing |

John Horton Slaughter

with his shotgun. |

the manager in his sleeping quarters, the bandits looted

the place and then headed for their cabin, which was located on top of

a steep hill that overlooked the town. Becker, who was still alive, waited

until the robbers were gone and then went to a nearby saloon to tell the

police. On the following morning, Constable Davis, who also served as the

sheriff of Graham County, organized a posse and began following the bandits'

trail, which clearly led to the cabin. There Chacon was waiting for the

posse with Franco and Morales; however, author R. Michael Wilson says that

there were two other men as well, besides Franco and Morales, making a

total of five bandits altogether. As Davis and his deputies approached

the cabin, suddenly Chacon and his men burst out the front door, running

for a pile of boulders and firing their guns wildly. The fighting continued

for several moments, but, eventually, the possemen stopped shooting long

enough to demand a surrender. One of the deputies was a man named Pablo

Salcido, who volunteered to approach the gang's position and speak with

them. After calling out to Chacon, Salcido was invited to move forward,

but, when he exposed himself, Chacon fired a single shot with his rifle

and struck the deputy in the head, killing him instantly. The fighting

immediately resumed and it lasted until over 300 rounds of ammunition had

been expended. Near the end of the skirmish, Franco and Morales chose to

make a run for it, leaving Chacon to fend for himself. A few of the possemen

went after the fleeing bandits, killing them both, and when the return

fire ceased they were able to move in and capture Chacon, who was temporarily

paralyzed by bullet wounds to his chest and shoulder.

The gunfight at Morenci was the bloodiest shootout in

the town's history and when it was over Chacon was taken to jail and his

gang members were either killed or in hiding. First Chacon was put in the

Clifton Jail and then he was sent to Solomonville to face the court for

the murder of Pablo Salcido. Judge Owen T. Rouse sentenced Chacon to hang

on July 24, 1896, but his case was appealed on May 26, after the bandit

pleaded innocent. Chacon claimed he would never kill his friend, who he

had worked with years before as cowboys. For this, Chacon was moved to

Tucson to await the Supreme Court's decision, but they affirmed the lower

court's ruling and he was sent back to Solomonville to be hanged on June

18, 1897. However, on June 9, Chacon escaped from his jail cell once again.

R. Michael Wilson says that the "jail's walls were ten inches of adobe

with a double layer of two inch pine boards held together with five inch

nails." Wilson says that if Chacon dug his way through the walls it would

have created a lot of noise so the guards were suspected of "turning a

deaf ear." Author Jan Cleere contradicts this though and says that some

fellow prisoners played guitars and sang to cover up the sounds. Marshall

Trimble agrees with Cleere, but also says that a young Mexican woman distracted

the jailer by seducing him. Either way, Chacon was free again and he fled

back across the border into Sonora. Nobody ever discovered how Chacon was

supplied with tools for his escapes, though, according to Cleere, visiting

friends probably gave them to him one at a time. According to William MacLeod

Raine, Chacon went to Mexico and enlisted in the Rurales, but, after a

year and a half, he had a dispute with another soldier and returned to

banditry.

Burton C. Mossman

| At the turn of the century, Arizona was still the wild

place it had been for years previously, especially around the international

border. Armed robbery and rustling was so widespread that in March 1901

the territorial governor, Oakes Murphy, authorized the re-establishment

of the Arizona Rangers. Burton C. Mossman was the first captain of the

unit and his final accomplishment before resigning was tricking Augustine

Chacon into crossing the border, where he could be apprehended legally.

To do this, Mossman came up with an idea that involved posing as an outlaw

and recruiting the train robber Burt Alvord, who was a friend of Chacon,

to use him as a stool pigeon. However, to recruit Alvord, Mossman had to

find his hideout in Sonora, where he would be totally helpless against

both the bandits and Mexican authorities. Mossman had previously attempted

to capture Alvord and his gang, but they got away. This time, Mossman hoped

that Alvord would be willing to help him with Chacon and then surrender

in exchange for a lighter sentence and the reward money offered for Chacon's

head. On April 22, 1902, after traveling for several days by wagon and

on horseback, Mossman discovered Alvord's hideout, a small hut located

some distance away from San Jose de Pima. The captain approached the hut

unarmed and by chance he found Alvord standing alone outside while the

rest of the gang played cards inside. Mossman was first to introduce himself

and though Alvord was immediately alarmed about the presence of a police

officer at his hideout, he agreed to feed Mossman and listen to what he

had to say. When it was obvious that Mossman wasn't trying to fool Alvord,

the two men agreed to cooperate and that Billy Stiles would act as their

messenger for it would take a while for Alvord to find Chacon and convince

him to cross the Arizona border and somebody had to warn the captain of

when the bandits arrived. When he finally did catch up with Chacon, over

three months later, Alvord first had to go with him to the Yaqui River,

to sell some stolen horses, before going all the way back to the border.

As the bandits were nearing the rendezvous, Alvord sent Stiles ahead to

tell Mossman to meet them just south of the border, at the Socorro Mountain

Springs in Sonora.

Mossman and Stiles failed to meet Alvord and Chacon in

the Socorro Mountains, but, on the following night, they found the bandits

at the home of Alvord's wife. There, after exchanging names, Mossman and

the others agreed to cross the border, back into Arizona, on the next day

so they could steal some horses from Greene's Ranch that night. However,

when it came time, it was decided that it was too dark for stealing horses

so the party went back to their camp, which was located less than seven

miles from the border. According to Raine, just before daybreak on September

4, 1902, Alvord was preparing to leave when he "tiptoed" over to Mossman

and said: "I brought Chacon to you, but you don't seem able to take him.

I've done my share and I don't want him to suspect me. Remember that if

you take him you have promised that the reward shall go to me, and that

you'll stand by me at my trial if I surrender. You sure want to be mighty

careful, or he'll kill you. So long." When Chacon awoke later that morning

his suspicions were aroused when he found that Alvord was no longer in

camp. After breakfeast, Stiles suggested that they go steal the horses

in daylight, but Chacon was uninterested and said he was going back to

Sonora. Mossman knew his time to act was now. Chacon and Stiles were sitting

on the ground next to each other when Mossman stood up. First he asked

for and received a cigarette from Chacon, then, as he dropped the twig |

Captain Burton C. Mossman

Burt Alvord

at Yuma Territorial Prison in 1904.

|

he used to light his cigarette, Mossman pulled out his revolver

and aimed it at Chacon. According to Raine, Mossman said: "Hands up, Chacon,"

to which the bandit said: "Is this a joke?" Mossman replied: "No. Throw

your hands up or you're a dead man." Chacon then said: "I don't see as

it makes any difference after he is dead whether man's hands are up or

down. You're going to kill me anyway, why don't you shoot?" Mossman had

Stiles disarm Chacon and then put him on a horse for the journey to the

railroad, where they boarded a train to Benson. Of note is that several

times Chacon attempted to escape by throwing himself off his horse, presumably

at a place where Mossman couldn't easily follow, such as a steep hillside

or something similar.

Death

The final capture of Chacon proved to be anticlimactic,

but Mossman's plan worked exactly as he hoped. At Benson, Mossman delivered

Chacon to the new sheriff of Graham County, Jim Parks, and from there he

went back to Solomonville. Because he had already been sentenced to hang,

Chacon's appearance in the Solomonville courthouse was merely to set a

new date for execution. The first day chosen was November 14, 1902, but

a group of local citizens petitioned to have Chacon's sentence reduced

to life in prison. Popularity wasn't going to save him though and the court

decided to hang Chacon on November 21, 1902. While waiting, Chacon was

held in a specially built steel cage that was under heavy guard. Also,

the scaffold on which Chacon was to hang had been built specifically for

him in 1897, but he escaped before it could be used. A large fourteen-foot

adobe wall was built around the scaffold so only the people with invitations

could view the hanging. When the day of execution came, Chacon had a good

breakfast and was then permitted to see two of his friends, Jesus Bustos

and Sisto Molino. He was also allowed to see the Catholic priest several

times that day and after lunch he was given a shave and a new black suit

to wear. Chacon was delivered to the scaffold at 2:00 pm and, as he entered

the courtyard, about fifty people were waiting to greet him. The bandit

chief, who had for over a decade eluded the law, asked for a cigarette

and a cup of coffee before death and then began an unprepared thirty-minute

speech to the crowd. Speaking in Spanish with and English interpreter,

Chacon claimed he was innocent of killing his friend, Pablo Salcido, or

anybody else for that matter, but he did say that he was guilty of stealing

and "many other things." After a second cigarette and cup of coffee, Chacon

requested that he be allowed to live until 3:00 pm, but was denied. While

walking up the steps of the scaffold, Chacon shook the hands of his friends

and admirers. When the rope was in place and the executioner was ready,

Chacon's final words were "Adios, todos amigos." On the day after the execution,

the Arizona Bulletin reported: "[A] nervier man than Augustine Chacon never

walked to the gallows, and his hanging was a melodramatic spectacle that

will never be forgotten by those who witnessed it."

The native Mexican-born actor Rodolfo Hoyos, Jr., played

Chacon in a 1955 episode of the syndicated television series Stories of

the Century, starring and narrated by Jim Davis.

Michael Pate played Chacon in the 1963 episode "The Measure

of a Man" of the syndicated western television series, Death Valley Days,

narrated by Stanley Andrews. In the story line, Burt Mossman (Rory Calhoun)

convinces a reluctant Burt Alvord (Bing Russell), who is promised a light

sentence on his surrender, to set a trap to catch the elusive bandit Chacon.

Mossman, though no longer technically an Arizona Ranger has Chacon handcuffed

and orders Alvord to toss away the key. Chacon is hanged thereafter for

the past conviction of which he had escaped.

Augustine Chacon was known to have fathered at least one

child in his lifetime, a son, and his descendants still live today. In

1980, some of Chacon's family members dedicated a marble gravestone at

the San Jose Cemetery, which holds his remains.

|

McCanles Gang (1861) from Wikipedia

| The McCanles Gang or McCandless Gang was an alleged outlaw

gang active in the early 1860s that was accused of train robbery, bank

robbery, cattle rustling, horse theft, and murder. On July 12, 1861, some

of its supposed members, including alleged leader David McCanles, were

killed by "Wild Bill" Hickok during a confrontation at a Pony Express station

in the Nebraska Territory. The incident was among the earliest to frame

Hickok's later reputation as a legendary gunfighter.

Historians have since argued that the victims of the shooting

were innocent and that their only crime was to cross paths with Hickok.

Questions remain surrounding the veracity of the allegations of the gang's

crimes, and whether the McCanles Gang ever existed at all.

McCanles incident

The legend of the McCanles "Gang" seems to be traceable

to a single incident between a young Hickok (not yet known as "Wild Bill")

and a rancher named David Colbert McCanles at Rock Creek Station, a stagecoach

and Pony Express station in southern Nebraska, near present-day Fairbury.

McCanles, a former sheriff of Watauga County, North Carolina, was known

as a local bully and had earlier had an argument with Hickok over the latter

"stealing" his mistress, Sarah (Kate) Shull.

Background

Prior to the incident, McCanles leased a cabin and well

on the east side of Rock Creek to the Russell, Waddell, and Majors freight

company to be used as a relay station for the Overland Stage Company and

the Pony Express mail service. The company hired Horace G. Wellman as station

agent and later |

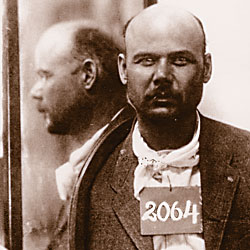

David C. McCanles, 1860 |

arranged to purchase the land in installments. In April or

early May of 1861, 23-year-old James Butler Hickok was hired by the station

as a stock tender. He quickly became a target of harassment by McCanles,

who teased Hickok about his girlish build and nicknamed him "Duck Bill"

for his long nose and protruding lips.

The freight company soon fell behind on paying its installments,

and on July 12, 1861, McCanles arrived at the station with his 12-year-old

son Monroe (or William Monroe), his cousin James Woods, and another employee,

James Gordon, demanding to see Horace Wellman in order to collect a long-overdue

payment. There are several different versions of what happened next. In

some versions, McCanles was initially met by Wellman's wife and Hickok

at the door, who told him that Wellman was either unavailable or unwilling

to meet with him. Other accounts suggest that Wellman himself was present

for the confrontation. At some point, either by invitation or by force,

McCanles entered the station cabin and argued with the occupants. He was

then shot by Hickok, who was hiding behind a curtain. McCanles's son immediately

rushed into the building. Woods and Gordon, like McCanles, were unarmed

and attempted to flee, but Hickok stepped from the cabin and wounded both

with his pistols. The two men were then killed by other members of the

relay station, Gordon by station employee J.W. "Doc" Brink with a shotgun

blast and Woods by Horace Wellman (or Wellman's wife), who hacked him to

death with a gardening hoe. Hickok was not reported as wounded. During

the attack, McCanles' son Monroe was able to escape via a dry creekbed.

This violent encounter was an early contributor to Hickok's

reputation as a legendary gunman, as reported years later in Harper's Monthly,

where the story was wildly sensationalized. According to the story, Hickok

single-handedly killed the nine "desperadoes, horse-thieves, murderers,

and regular cutthroats" known as the McCanles Gang "in the greatest one

man gunfight in history." During the battle, Hickok (armed with a pistol,

a rifle, and a Bowie knife), purportedly suffered 11 bullet wounds.

Aftermath

| David McCanles' brother James immediately filed an arrest

warrant for Hickok, Wellman, and "Doc" Brink, who were charged with the

murders. When the case was brought to trial, Monroe McCanles was not permitted

by the judge to testify and the court heard only the account given by the

station employees. The judge ruled that the defendants had acted in self-defense.

From The DeWitt Times News, as told by the foreman of

the company stations:

"At the time of this affair I was at

a station farther west and reached this station just as Wild Bill was getting

ready to go to Beatrice for his trial. He wanted me to go with him and

as we started on our way, imagine my surprise and uncomfortable feeling

when he announced his intention of stopping at the McCanles home. I would

have rather been somewhere else, but Bill stopped. He told Mrs. McCanles

he was sorry he had to kill her man then took out $35 [$923 in 2016 dollars]

and gave it to her saying: ‘This is all I have, sorry I do not have more

to give you.’ We drove on to Beatrice and at the trial, his plea was self-defense,

no one appeared against him and he was cleared. The trial did not last

more than fifteen minutes."

After this tragedy, some of the McCanles family moved

to Florence, Colorado and changed the spelling of the name to McCandless.

Hickok, making use of his new notoriety also changed his name after this

incident. After growing a moustache to hide his protruding upper lip, he

encouraged people to call him "Wild Bill" instead of "Duck Bill".

Witness accounts

|

James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok,

c. early 1860s |

The first account was published around 1882 by S. C. Jenkins

and S. J. Alexander, who had arrived at the ranch within two hours of the

shootout taking place and before the bodies were removed. According to

them, David McCanles' brother James was a Southern sympathizer and had

tried to persuade Hickok to join him and turn over the stage company's

stock. After Hickok's refusal, James threatened to kill him. Later that

afternoon, David and three others arrived with the intention of carrying

out the threat.

In 1883, D.M. Kelsey published Our Pioneer Heroes and

Their Daring Deeds, which contained a biography for "Wild Bill" based on

Hickok's own accounts. Hickok claimed he had killed six of the ten members

of the McCanles Gang, who had rushed in after using a log to batter the

station door down. Two of these he claimed to have killed in a knife fight

after he was wounded.

"I remember that one of them struck

me with his gun, and I got hold of a knife, and then I got kind o' wild

like, and it was all cloudy, and I struck savage blows, following the devils

up from one side of the room to the other and into the corners, striking

and slashing until I knew every one was dead."

The remaining four attackers then fled, and Hickok picked

up a rifle and shot one dead; another later died of his wounds.

"All of a sudden, it seemed like my

heart was on fire. I was bleeding everywhere. I rushed out to the well

and drank from the bucket, and then tumbled down in a faint."

The dead, according to Hickok, included David McCanles's

brothers James and Jack LeRoy McCanles; however, according to records,

Jack LeRoy McCanles was still alive in 1883 and was a "good citizen" of

Florence, Colorado. An account by William Monroe McCanles (the son of David

McCanles) appeared in the Fairbury Journal on September 25, 1930. Monroe

maintained that he had gone with his father to the station to collect money

and that they had been unarmed:

"Probably the motive for killing was

fear. Father had told Mrs. Wellman to tell her husband to come out. The

Wellmans were the folks who lived there and kept the station. She said

he wouldn't and father said if he wouldn't come out he would go in and

drag him out. I think rather than be man-handled, he killed father."

"Buffalo Bill" Cody’s visit to Major Israel McCreight

at The Wigwam in Du Bois, Pennsylvania, on June 22, 1908, remains a notable

event in Wild West history. On this occasion, Monroe McCanles was McCreight’s

houseguest and told Buffalo Bill about his father Dave McCanles having

been shot by "Wild Bill" Hickok. The "McCanles Incident” was then the subject

of controversy and debate by Wild West historians. Monroe McCanles disclosed

that at the age of twelve he had stood beside his father Dave McCanles

when Hickok shot him dead from behind a curtain. For the first time, Buffalo

Bill heard an alternative account of the event and remarked that he would

include the story in his projected autobiography. McCreight wrote articles

about the "McCanles Incident" for the rest of his life.

Legacy

Another son of David Colbert McCanles, Julius McCandless,

was the father of Commodore Byron McCandless (United States Navy), recipient

of the Navy Cross in World War I. David's great-grandson was Rear Admiral

Bruce McCandless (also USN), recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor

in World War II, and his great-great-grandson is Captain Bruce McCandless

II (also USN), a now-retired NASA astronaut who made the first untethered

spacewalk.

|

.

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|