| A few New Mexico Stage Stations

Soldier's Farewell Stage Station

'Soldiers Farewell Stage Station was a stagecoach stop

of the 1858-1861 Butterfield Overland Mail route before the company moved

to the central route (former Pony Express route). West of "Soldiers Farewell

Hill" on the west bank of a drainage arroyo,[3] the stop was on the Butterfield

Overland Mail route (1858-1861) in Grant County, New Mexico. According

to the Overland Mail Company Through Time Schedule, it was 150 miles (33½

hours) west of El Paso, Texas and 184½ miles (41 hours) east of

Tucson, Arizona. Located 42 miles east of Stein's Peak Station and 14 miles

southwest of Ojo de Vaca Station.

Ojo de Vaca Station - Wikipedia

Ojo de Vaca Station, was a Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach

station at Ojo de Vaca (Cow Springs), in New Mexico Territory. It was located

14 mi (23 km) northeast of Soldiers Farewell Station and 16 mi (26 km)

southwest of Miembre's River Station, later Mowry City, New Mexico. The

site is now Cow Springs Ranch located in Luna County, New Mexico.

History

Ojo de Vaca was a watering place on the old trail between

Janos, Chihuahua, Mexico to the Santa Rita copper mines. When Cooke's Mormon

Battalion was searching for a wagon route between the Rio Grande and California,

they intercepted the old Mexican road at this spring, then followed it

southward to Guadalupe Pass then westward and northward to Tucson, pioneering

the route known as Cooke's Wagon Road. In 1849, Cooke's road became the

major southern route of the forty-niners during the California Gold Rush

and Ojo de Vaca spring was one of the reliable watering places on what

became the Southern Emigrant Trail. Later Ojo de Vaca was a water station

on the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line and subsequently the Butterfield

company built their stagecoach station there. It remained an important

stop on this route until the long distance stagecoach lines ended in the

late 19th century.

Mesilla Station

Mesilla (also known as La Mesilla and Old Mesilla) is

a town in Doña Ana County, New Mexico, United States. The population

was 2,180 at the 2000 census. It is part of the Las Cruces Metropolitan

Statistical Area.

During the American Civil War, Mesilla briefly served

as capital of the Confederate Territory of Arizona.

The Mesilla Plaza is a National Historic Landmark.

History

The village of Mesilla was incorporated in 1848, after

the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo moved the U.S.-Mexico border south of the

village of Doña Ana, placing it in the United States. A small group

of citizens, unhappy at being part of the United States, decided to move

south of the border. They settled in Mesilla at this time.

By 1850, Mesilla was an established colony. By this time,

its people were under constant threat of attack from the Apache. By 1851,

the attacks caused the United States to take action to protect its people

just to the north of the border, in the Mesilla Valley. They did this by

creating Fort Fillmore. As a result of the fort, the United States declared

the Mesilla Valley region part of the United States. Mexico also claimed

this strip of land, causing it to become known as "No Mans Land." This

boundary dispute, which was officially caused by a map error, was resolved

in 1853, with the Gadsden Purchase. Mesilla became a part of the United

States, as well as the southern part of New Mexico and Arizona.

Two battles were fought at or in the town during the Civil

War. Mesilla served as the capital of the Confederate Territory of Arizona

in 1861-1862 and was known as the "hub", or main city for the entire region.

Recaptured by the Volunteers of the California Column, it then became the

headquarters of the Military District of Arizona until 1864.

During the "Wild West" era, Mesilla was known for its

cantinas and festivals. The area attracted such figures as Billy the Kid,

Pat Garrett and Pancho Villa. The village was also the crossroads of two

major stagecoach lines, Butterfield Stagecoach and the Santa Fe Trail.

The village of Mesilla was the most important city of the region until

1881.

In 1881, the Santa Fe Railway was ready to build through

the Gadsden Purchase region of the country. Mesilla was naturally seen

as the city the railroad would run through. However, the people of Mesilla

asked for too much money for the land rights, and a land owner in nearby

Las Cruces, New Mexico, a much smaller village than Mesilla, stepped in

and offered free land. The city of Mesilla has not grown much since, and

Las Cruces has grown to a population of an estimated 95,000 people (2010)

and is currently the second largest city in New Mexico.

La Mesilla Historic District, which includes Mesilla Plaza,

was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1961.

The Fountain Theatre, except for 12 years, has been in

operation since the early 1900s

In 2008, the Roman Catholic parish church of San Albino

was raised to the status of minor basilica by the Holy

The gazebo in the center of the plaza was torn down and

rebuilt due to unnoticed structural problems that made the gazebo unsafe.

Demolition started in October 2013, ending next year in May 2014 for the

annual 'Cinco de Mayo' celebration.

Geography

Mesilla is located at 32°16'22"N 106°48'3"W (32.272776,

-106.800965). According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has

a total area of 5.4 square miles (14 km2), all of it land.

Demographics

Historical population

Census Pop. %±

1950 1,264 —

1960 1,264 0.0%

1970 1,713 35.5%

1980 2,029 18.4%

1990 1,975 ?2.7%

2000 2,180 10.4%

2010 2,196 0.7%

Est. 2014 1,880 [5] ?14.4%

U.S. Decennial Census

As of the census of 2000, there were 2,180 people, 892

households, and 595 families residing in the town.[8] The population density

was 407.0 people per square mile (157.0/km²). There were 981 housing

units at an average density of 183.1 per square mile (70.7/km²). The

racial makeup of the town was 73.99% White, 0.23% African American, 1.01%

Native American, 0.23% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 20.69% from other

races, and 3.81% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race

were 52.20% of the population.

There were 892 households out of which 25.6% had children

under the age of 18 living with them, 53.5% were married couples living

together, 9.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.2%

were non-families. 27.8% of all households were made up of individuals

and 8.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The

average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 2.99.

In the town the population was spread out with 22.2% under

the age of 18, 7.9% from 18 to 24, 23.4% from 25 to 44, 29.4% from 45 to

64, and 17.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43

years. For every 100 females there were 90.9 males. For every 100 females

age 18 and over, there were 90.7 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $42,275,

and the median income for a family was $51,181. Males had a median income

of $30,500 versus $25,000 for females. The per capita income for the town

was $25,922. About 6.3% of families and 9.4% of the population were below

the poverty line, including 7.4% of those under age 18 and 5.8% of those

age 65 or over.

Shakespeare, New Mexico

Shakespeare is a ghost town in Hidalgo County, New

Mexico, United States.[2] It is currently part of a privately owned ranch,

sometimes open to tourists. The entire community was listed on the National

Register of Historic Places in 1973.

History

Founded as a rest stop called Mexican Springs along a

stagecoach route, it was renamed Grant after the Civil War, after General

U. S. Grant. When silver was discovered nearby it became a mining town

called Ralston City, named after financier William Chapman Ralston. It

was finally renamed Shakespeare, and was abandoned when the mines closed

in 1929.

On November 9, 1881, Old West outlaws "Russian Bill" Tattenbaum

and Sandy King, both cattle rustlers and former members of the Clanton

faction of Charleston, Arizona Territory, were lynched in Shakespeare,

and their bodies were left hanging for several days as a reminder to others

that lawlessness would not be tolerated. The two had been captured by gunman

"Dangerous Dan" Tucker, who at the time was the Shakespeare town marshal.

|

| Lamy, New Mexico - Wikipedia

Lamy is a census-designated place (CDP) in Santa Fe County,

New Mexico, United States, 18 miles (29 km) south of the city of Santa

Fe. The community was named for Archbishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy, and lies

within the Bishop John Lamy Spanish Land Grant, which dates back to the

eighteenth century.

Lamy is part of the Santa Fe, New Mexico, Metropolitan

Statistical Area. The population was 218 at the 2010 census. The former

Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad (ATSF), now the Burlington Northern

Santa Fe (BNSF), passes through Lamy. This railroad, usually called just

the "Santa Fe," was originally planned to run from Atchison, Kansas, on

the Missouri River, to Santa Fe, the capital city of New Mexico, and then

points west. However, as the tracks progressed west into New Mexico, the

civil engineers in charge realized that the hills surrounding Santa Fe

made this impractical. Hence, they built the railway line though Lamy,

instead. Later on, a spur line was built from Lamy to Santa Fe, bringing

the railroad to Santa Fe at last. In 1896 the Fred Harvey Company built

the luxurious El Ortiz Hotel here. Thus Lamy became an important railroad

junction. In 1992 the spur line was taken over by the Santa Fe Southern

Railway, which operates a popular excursion train, using vintage passenger

railcars and modern freight cars, between Santa Fe and Lamy.

The significance of Lamy as a railroad junction is related

in the Oscar-nominated documentary, The Day After Trinity (1980), about

the building of the first atomic bomb, and is referred to by instrumental

group the California Guitar Trio in a five-part suite Train to Lamy on

their second album Invitation (1995).

Geography

Lamy is located at 35.480°N 105.88°W.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP

has a total area of 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2), all land.

Demographics

As of the census of 2000, there were 137 people, 55 households,

and 33 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 126.2 people

per square mile (48.5/km²). There were 64 housing units at an average

density of 59.0 per square mile (22.7/km²). The racial makeup of the

CDP was 74.45% White, 2.92% Native American, 18.25% from other races, and

4.38% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 44.53%

of the population.

There were 55 households out of which 40.0% had children

under the age of 18 living with them, 49.1% were married couples living

together, 10.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.2%

were non-families. 29.1% of all households were made up of individuals

and 9.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The

average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.18.

In the CDP the population was spread out with 27.7% under

the age of 18, 10.2% from 18 to 24, 26.3% from 25 to 44, 28.5% from 45

to 64, and 7.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34

years. For every 100 females there were 95.7 males. For every 100 females

age 18 and over, there were 98.0 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $43,333,

and the median income for a family was $27,083. Males had a median income

of $25,568 versus $0 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was

$16,765. There were 17.5% of families and 20.5% of the population living

below the poverty line, including no under eighteens and none of those

over 64.

Notable people

Poet James Thomas Stevens resides in Lamy.

Ivo Watts-Russell, Co-founder of music label 4AD, resides

in Lamy.

Museum

The Lamy Railroad and History Museum, located in the historic

"Legal Tender" restaurant building, is dedicated to preserving local history

and heritage, with emphasis on the railroads and their impact on the area.

The museum buildings, formerly the Pflueger General Merchandise Store (built

in 1881) and the attached Annex Saloon (built in 1884), are listed on the

National Register of Historic Places. The Legal Tender Saloon and Restaurant

re-opened as the Legal Tender at The Lamy Railroad & History Museum

in March 2012, after 14 years. The restaurant and museum are run as a non-profit

and the waitstaff are volunteers. It is open Thursday through Sunday.

Local folklore

There are multiple accounts, particularly in the Santa

Fe New Mexican at the time (March 26, 1880) of a sighting of a "fish-shaped

balloon" which contained "about ten human occupants" from which was heard

singing, music, and shouting "in an unknown language". A rose tied to a

letter written with "unknown characters" and a cup of "unusual workmanship"

were reportedly dropped from the vehicle. According to accounts, the following

day a person unknown to residents purchased both items for "a large sum

of money", declaring them "of Asiatic origin".

|

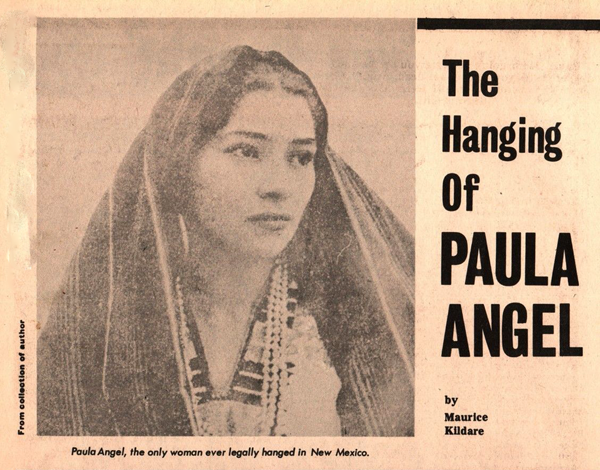

The hanging of Paula Angel - Wikipedia

Classification: Murderer

Characteristics: The victim refused to leave his wife

for her

Number of victims: 1

Date of murder: March 23, 1861

Date of arrest: Next day

Date of birth: 1842 ?

Victim profile: Juan Miguel Martin (her married lover)

Method of murder: Stabbing with knife

Location: San Miguel County, New Mexico, USA

Status: Executed by hanging at Las Vegas on April 26,

1861 |

|

It's not clear today how old she was -- nineteen, maybe,

or twenty-six, or twenty-seven -- the reports all differ. It's not even

clear what her true name was: Paula Angel by most accounts, but she was

also called Pablita Martin. But the most pressing questions, still unanswered

nearly 150 years after her execution, are why she was hanged in the first

place and how the sheriff managed to bungle the job so badly.

Paula Angel was the first and last woman ever executed

in New Mexico (while it was yet a territory). Her crime: she stabbed her

married lover, Juan Miguel Martin, to death when he tried to end their

affair. Her execution was on April 26, 1861, in San Miguel, now Las Vegas.

Anyone familiar with historical crimes and trials, particularly

those involving women, will marvel at such an outcome. A capital conviction

for stabbing a lover, a crime passionel? That's certainly not the outcome

one would expect for that era (or this era, for that matter; today we'd

label it second-degree murder at worst).

One explanation for Miss Angel's hanging is that the newspapermen

never got the story. Decades later, the wire services circulated very brief

accounts of her trial and execution under headlines such as "The Story

The Newspapers Missed." So she may well have lacked the greatest champion

anyone facing a murder charge can have: public opinion -- the verdict of

the greater jury. Throughout the nineteenth century, there was a

universal revulsion for the execution of women, no matter what their crime,

and judges and juries were anxious to find a reason to acquit a woman.

But the authorities in New Mexico Territory were eager

to see her hanged. The accounts that survive today report that the jailer

taunted her every day leading up to her execution -- "I'm going to hang

you until you're dead, dead, dead," is the quote attributed to the sheriff.

What was her social status? Was she a prostitute? Was

she a violent menace to the community? Had she committed other terrible

acts? Was she unrepentant? Did she sullenly testify at her trial and put

in a poor appearance on her own behalf? Most importantly, was she

ugly? The accounts available today don't say.

When it came time to launch Angel into eternity, the sheriff

did not build a gallows. He selected a sturdy cottonwood tree outside of

town. Paula Angel was driven there on a wagon, forced to ride on her own

coffin to the site of her execution, which was witnessed by ranchers and

townsmen. The sheriff fixed the rope to the tree, garlanded her with hemp,

and then resumed his seat on the wagon and hawed the horses. But he'd made

an error. He forgot to tie her hands behind her.

Paula Angel managed to get her fingers underneath the

rope in a last pitiful effort to save her own neck, and she struggled on

the end of the rope. It must have been an awful sight to see. The crowds

surely voiced loud complaints. The sheriff was forced to put the wagon

beneath her a second time, to cut her down, retie the rope amid the jeers

and catcalls, properly secure her hands and feet, and to repeat the process.

She did not survive her second hanging.

And there hasn't been one woman executed in New Mexico

since. Rarely has any woman from that state even faced the possibility,

though a few years ago Linda Henning nearly became the second woman executed

there -- and she certainly deserved it. Fans of Court TV will recognize

the name, since Court TV has rebroadcasted Henning's bizarre trial more

than once.

She was tried for the cooly planned and bloody murder

of Girly Chew Hossencofft, the estranged wife of her boyfriend, in one

of the weirdest trials of the century. But the jury rejected the death

penalty. The reason Henning agreed to involve herself in the murder of

a woman she had not even met: Henning was convinced that Girly Chew was

a reptilian alien queen from another galaxy.

---------------------

Paula Angel: The Only Woman Ever Hanged in New Mexico

(actually

there were two)

By Robert Torrez

New Mexico's history is full of marvelous stories about

ordinary people who happen to end up in the historical record when they

get caught up in extraordinary circumstances. As we leaf through the stories

of such individuals, one often wonders how much of what has been passed

on to us about their lives is fact and how much of it is myth. The following

is the story of one such person, Paula Angel, a fascinating and mysterious

woman about whom we know very little, but who has for several decades been

endowed by our history books with the dubious distinction of being "the

only woman ever hanged in New Mexico."

Paula Angel's story was brought to wide public attention

when an article about her was published in The New Mexican, on April 26,

1961, under the title, "Bizarre Frontier Hanging Recalled." The story was

timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of her execution in 1861 at

Las Vegas, New Mexico. Reporter Ernie Thwaites indicated the story was

"as told" to him by then New Mexico District Court Judge Luis E. Armijo.

The essential elements of Judge Armijo's story are as

follows. Paula Angel, he tells us, earned her small niche in history on

April 26, 1861, when she was executed for a crime that was “as old as Eden."

Paula was arrested and brought to trial during the March 1861 term of San

Miguel County District Court for the murder of a lover who had jilted her.

Found guilty of first- degree murder, Judge Kirby Benedict imposed upon

her

the only sentence allowed by New Mexico’s territorial law—death by hanging.

The date of her execution was set for Friday, April 26, 1861.

While awaiting her appointed day of execution, San Miguel

County Sheriff Antonio Abad Herrera daily taunted his prisoner: "Paula

Angel, you have only _____ days more to live," reducing the figure from

day to day. When April 26th dawned, a large crowd had gathered in Las Vegas

from every corner of the territory to witness the hanging. Sheriff Herrera

selected a large cottonwood in a nearby grove and took Paula there in a

wagon that also carried her coffin. He drove the wagon under the noose

that dangled from a limb, halted, and placed the noose around her neck.

Then, "perhaps overeager... [he] whipped the team and wagon away."

As Herrera pulled away, he glanced over his shoulder and

was horrified to see that he had forgotten to tie her arms. Instead of

being hanged, Paula had grabbed hold of the rope and was "frantically trying

to pull herself upward from the strangling noose." The sheriff leaped from

the wagon and grasped her around the waist, trying to pull her downward,

while Paula desperately clung to the rope. But the spectacle was too much

for the startled crowd, and they rushed forward, pulled Herrera to the

ground, and cut Paula down. Herrera protested, noting that justice had

not been done, but he was shouted down by the crowd which contended that

Paula had been hanged—albeit unsuccessfully—and the sentence carried out.

Then Colonel J. D. Sena of Santa Fe, "a prominent and

forceful man," stepped forward and addressed the crowd. Reading from the

warrant of execution, he emphasized Paula had to be “hanged by the neck

until dead.” The crowd backed away, and Paula Angel was again stood on

the back of the wagon, this time with her hands tied behind her back, “and

with little further delay gained her own particular claim to fame.…”

Judge Armijo’s story of Paula Angel’s hanging contains

many elements of fact, an unusual characteristic for a tale that seems

to have reached us largely through oral tradition. Several of the individuals

named in the story by Judge Armijo are accurate for the time and place.

These include San Miguel County Sheriff Antonio Abad Herrera, District

Court Judge Kirby Benedict, defense attorney Spruce M. Baird, and “Colonel”

Jose D. Sena.

The presence of "Colonel" Jose D. Sena and the role he

played that fateful day is most plausible. Jose D. Sena had a long and

distinguished public career and possessed a well-documented talent for

public speaking. At his funeral in 1892, Sena was eulogized as a popular

speaker whose "eloquence and rhetoric often inspired the multitudes to

the highest enthusiasm." It is not difficult to imagine him standing before

that crowd in Las Vegas in 1861, pointing out that Paula’s bungled hanging

did not comply with the letter of the law.

However, the use of a military rank with Jose D. Sena's

name suggests that parts of this story developed after the actual event.

Sena entered military service in July 1861, three months after Paula's

hanging. At that time, he was mustered in as a captain in the New Mexico

Volunteers and later participated in the Civil War battles at Valverde

and Apache Pass (Glorieta) and several Indian campaigns. He was promoted

to the rank of Major in 1863, but there is no indication he ever attained

the rank of colonel, although his son, Jose D. Sena Jr., was later a colonel

in the New Mexico National Guard.

The fascinating and entertaining accounts of Paula's execution,

however, are unsubstantiated by a single shred of primary documentation.

The following will explore this historian’s efforts to determine whether

or not someone named Paula Angel was in fact, hanged at Las Vegas on April

26, 1861, and if so, whether she has been the only woman executed in New

Mexico.

The question of whether Paula was the first or the only

woman to be hanged in New Mexico is answered by a marvelous manuscript

found in the Spanish Archives of New Mexico. This folio of ancient documents

records the story of two women from the Pueblo of Cochiti who were hanged

together in Santa Fe on January 26, 1779. On that date, Maria Josefa and

her daughter, Maria Francisca, suffered the penalty of death for the premeditated

murder of Francisca's husband.

So while we can easily determine that this distinction

is not Paula’s alone, documenting the facts of her own story has proven

more of a challenge. For several years, this writer harbored doubts that

her hanging had actually taken place. This skepticism surfaced during an

on-going project to compile a complete and accurate list of the legal executions

that took place in territorial New Mexico (1846 -1912). To accomplish this,

it was necessary to establish two basic criteria. The first required primary

evidence of an indictment, trial, or other judicial actions that documents

the due process that distinguishes legal hangings from the dozens of lynchings

that took place during that period of our history.

The second required primary evidence that the execution

took place. It became clear early in the course of this research that documentation

of a death sentence imposed through due process was, in itself, insufficient

evidence that an execution had actually taken place. New Mexico's territorial

judges imposed many death sentences that were not carried out, principally

because governors frequently exercised their privilege of executive clemency

and issued a number of pardons and commutations of death sentences to life

imprisonment. Additionally, a few condemned persons died while awaiting

execution, while others cheated the hangman by escaping from the territory's

notoriously inadequate jails. William Bonney, better known to us as Billy

the Kid, is merely the most famous example of a condemned prisoner who

escaped from jail while awaiting execution.

The records needed to fully document Paula Angel's case

have been difficult to find. Several authors have cited the handwritten

transcripts of Paula Angel's trial and sentence, presumably located at

the San Miguel County Courthouse in Las Vegas. However, between the times

when these books were published and when the San Miguel County Territorial

District Court records were transferred to the New Mexico State Records

Center and Archives in Santa Fe in 1976, Paula's case file had disappeared.

There are only two extant items related to Paula's trial

at the State Records Center and Archives, New Mexico's official repository

for territorial judicial records. The first consists of an entry of the

case name and number, Territory of New Mexico vs Paula Angel, 73b, in a

surviving San Miguel County District Court docket index. The second item

is an April 3, 1861, entry in the Executive Record where New Mexico Territorial

Governor Abraham Rencher notes he "issued his writ for the execution of

Paula Angel, sentenced to be hung, at the March term, 1861, of the District

Court, for San Miguel County."

This scant information seems to indicate Paula was probably

tried and condemned through due process, but it does not constitute the

primary evidence needed to prove the execution actually took place. Even

the newspapers of the period failed to carry a report of what should have

been a well-attended public event. The firing on Fort Sumter on April 12,

1861, meant that by the time Paula Angel was scheduled to hang, the territory's

few newspapers were more concerned with reporting the unfolding events

of the Civil War as well as rumors of silver strikes in southwest Colorado.

Was it possible that during these trying and undoubtedly

hectic days, Paula could have been set free or had her sentence commuted?

This possibility was reinforced when the Las Vegas Daily Optic, commenting

on a 1907 case of two women being tried in Sierra County for capital murder,

noted emphatically that "No woman has ever been hanged in New Mexico."

Other newspapers in the territory made the same claim, and while it is

no surprise these papers did not know of the 1779 hanging mentioned earlier,

it does not seem likely the Las Vegas newspaper would have been unaware

of Paula Angel's story.

Furthermore, there is among the vast treasure of Las Vegas

folklore the tale of an unnamed weeping woman, or llorona as these wandering

spirits are called, which tells of a young woman who was condemned to hang

for killing her lover. As related by Edward Garcia Kraul and Judith Beatty

in The Weeping Woman, Encounters with La Llorona, when the time came for

this woman to be hanged, no one dared "pull the rope" for fear her spirit

would come back to haunt them. Consequently, she was set free, but when

she died years later, her spirit was condemned to wander the hills at the

outskirts of Las Vegas because she had not expiated her heinous crime.

Could this story have been based on what might have happened to Paula Angel

and explain why there seemed to be no primary evidence of her hanging?

Part of the answer to this historical puzzle was provided

by Julian Josue Vigil’s publication of an old folk ballad entitled La Homicida

Pablita. Vigil determined that Juan Angel, Paula’s cousin, had composed

the ballad in 1861 to commemorate her tragic crime and death. Juan Angel’s

ballad includes several elements of the story passed on to Judge Armijo

by his grandmother. As the ballad unfolds, one can visualize Paula's trial

and feel the heavy burden of the death sentence imposed on her. We shudder

as the closing cell door brings Paula to full realization of her disgrace

and the fate that awaited her. The ballad even describes her final ride

on the wagon that carried her to the gallows.

But while folklore often complements and provides direction

for research on local history, this ballad still was not the primary evidence

needed to determine what happened to Paula Angel. It was not until quite

recently that the most important but elusive piece of documentation showed

up in the most unlikely of places—the Huntington Library in San Marino,

California.

The Huntington’s William Gillet Ritch Papers, a collection

of nearly two thousand documents extracted from New Mexico’s archives more

than a century ago, contains the original warrant issued by Governor Abraham

Rencher for the execution of Paula Angel. The document, dated April 3,

1861, is written in Spanish and contains language rather typical of the

genre. Addressed to the Sheriff of San Miguel County, it opens with "Greetings,"

and continues,

Whereas I have received official information

that at the March 1861 term of District Court, held in and for the county

of San Miguel, in the Territory of New Mexico, where, one Paula Angel,

was convicted at said court of the crime of murder committed against the

body of one Miguel Martin, and was sentenced by said court to suffer the

penalty of death:

With this you are ordered that on the

26th of April of 1861, you take the said Paula Angel from the jail of the

County of San Miguel, in which she now finds herself incarcerated, to some

appropriate place within the limits of said county, and within a distance

of one mile from the seat of that county, and that between the hours of

ten in the morning and four in the afternoon of said day, 26th of April

1861, you then and there hang the said Paula Angel by the neck until she

is dead, dead, dead; and may God have mercy on her soul.

Here is the "writ [of] execution" Governor Rencher had

noted in the Executive Record of that date! The final piece of documentation

needed to complete the search for Paula’s story is on the reverse side

of Governor Rencher's warrant. It consists of a simple handwritten statement

and signature of San Miguel County Sheriff Antonio Abad Herrera. There,

Herrera, perhaps still a bit shaken by the day's events, certified compliance

with the order to hang Paula Angel with the simple phrase, "Retornado y

cumplido este mandato, hoy Abril 26 de 1861."(This order was completed

and returned today, April, 26, 1861)

We now can be reasonably certain about the basic facts

surrounding Paula Angel's execution. Someday the missing judicial case

file may surface and provide us details of her indictment and trial, and,

possibly, something about Paula herself. For now, we can certainly relieve

her of the dubious distinction of being “the only woman hanged in New Mexico.”

But this does not mean we should forget her story. In fact, we should continue

to tell it, not only because it is a splendid tale deserving of being told,

but also because it serves as a wonderful example of how myth and history

often combine to provide us with colorful and fascinating views of our

frontier past.

----------------

Observations on the demise of Paula Angel

By Don Bullis

Historical researchers love to deal with anomalies, and

the matter of Paula Angel, also known as Pablita Martin, is an anomaly

in several ways.

In the first place, she was the only woman to be legally

hanged in New Mexico. That alone makes her stand out in a crowd of 62 men

who were hanged between 1847 and 1923. But there is much more to her story.

Her crime was murder. On March 23, 1861, she stabbed her

lover, Miguel Martin. Miguel was no paragon of virtue, being married to

another woman at the time, and the father of five children. As the story

goes, he'd announced to Paula that he wanted to break off the affair, and

she'd requested a final assignation. As they embraced one last time, she

plunged a butcher knife into his back. Paula was 26 or 27 years old at

the time.

One source mentions in passing that Paula lived in the

San Miguel County town of Loma Parda, with her parents. Loma Parda was

at the time a collection of buildings along the Rio Mora that had become

what some referred to as the most sinful town in New Mexico, called 'Sodom

on the Mora.'

The community catered to an assemblage of gamblers, harlots

and saloon keepers who provided their unseemly services to the soldiers

at Fort Union, six miles away. No mention is made as whether Paula's crime

was committed in Loma Parda, but the town would have been in full swing

at the time since Fort Union had been in operation for about 10 years.

It is most unlikely that Paula was one of the town's prostitutes.

Paula was arrested within a day or so of the killing,

and oddly in any context, she went on trial only five days later, on March

28. Representing her before the court of Judge Kirby Benedict was attorney

Spruce M. Baird. There is no indication that Paula had much in the way

of resources, and yet her lawyer was high profile and well known. Baird

had successfully defended Major R. H. Weightman in the killing of F. X.

Aubrey at Santa Fe in 1854. He was also involved in land grant litigation

and he'd run for a seat in the U. S. Congress less than two years earlier.

Baird argued her case in both Spanish and English. She

was, he said to the jury, "disturbed by her lover's rejection. Do not be

so cold in soul as to demand death of this fair maiden who has been wronged

by an uncaring adulterer." It didn't help. On that very afternoon she was

convicted and sentenced to die by hanging on April 26. In yet one more

interesting twist, Judge Benedict ordered Paula to pay for all the costs

of legal action against her, including her own hanging.

At this late date it is impossible to understand the social

dynamic of Las Vegas, New Mexico, in 1861. It seems, though, that Paula

was not universally liked by her fellow citizens. In fact, the Sheriff,

Antonio Abad Herrera, harangued her daily, reminding her that he was going

to hang her until she was "dead, dead, dead."

A word about Sheriff Herrera is in order. His law enforcement

career seems to have been quite short. Records show that Jose Sena was

appointed sheriff of San Miguel County in December 1860. Herrera is known

to have been in office at the time of the Angel matter, but Juan Bernal

was elected sheriff in September 1861. Herrera served less than one year

in office.

And when execution day came, Sheriff Herrera further displayed

his ineptitude. He had identified a cottonwood grove where the hanging

would take place, and on the appointed day he drove to the spot. Paula

was obliged to ride on the back of the wagon, seated upon her own coffin.

Once there, Herrera drove his team under the tree, then he stepped to the

rear of the wagon and put the noose around Paula's neck. Next, according

to one source, "he eagerly jumped on to the wagon seat and popped the reins

for the horses to go forward."

The problem was that in his haste he'd failed to bind

Paula's hands. Herrera looked around to see the hapless woman swinging

about and holding on to the rope that was choking her. Herrera jumped down

from the wagon and ran to Paula, wrapped his arms around her waist, and

attempted to weigh her down and facilitate her demise.

Some of the spectators were so appalled at this turn of

events that they pushed the sheriff aside and cut Paula down. The problem

was that the execution order said that she was to be hanged by the neck

until she was dead. At that point she'd been hanged but was not dead. So

they did it all over again, with her hands and arms bound, and that time

Paula died.

There are a number of questions about this case that remain

unanswered. One has to do with the urgency of the matter: a trial five

days after the commission of the crime, and execution only four weeks later?

Was the case appealed, as were all capital cases, then and now? No source

offers answers.

The one possible explanation is that the people of New

Mexico, including the courts, were somewhat distracted by another matter:

The invasion of the territory by the Texas Confederates. In fact, on the

very day that Paula was tried, March 28, 1861, the Battle of Glorieta raged

only a few miles west of Las Vegas.

Looks like Paula Angel had bad luck all the way around.

|