Frontier gambler from Wikipedia

| The Frontier Gambler is one of the most recognizable

stock characters of the American West, usually portrayed as a gentlemanly

southerner living outside of the law. Historically, gamblers were of both

sexes, came from a variety of professions and class backgrounds, were of

many different nationalities, and were part of a well-respected profession.

As the west became increasingly populated and domesticated, the public

perception of gambling changed to a negative one and led nearly all of

the state and territorial legislatures to pass anti-gaming laws in and

effort to "clean up" their towns. The gambler continues to be a captivating

figure in the imagery of the west, representing the openness of its society

and invoking its association with risk-taking.

History

The heyday of gambling in the west lasted from 1850-1910.

Gambling was the number one form of entertainment in the west and nearly

everyone living there engaged in it at one time or another. Cowboys, miners,

lumberjacks, businessmen, and lawmen all played games of chance for pleasure

and profit. Whenever a new settlement or camp |

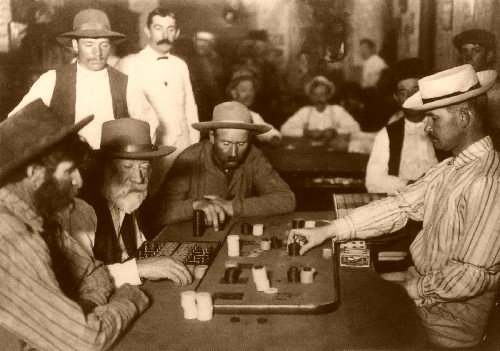

A faro game in progress. |

started one of the first buildings or tents erected would

be a gambling hall. As the settlement grew, these halls would become larger

and more elaborate in proportion. Gaming halls were typically the largest

and most ornately decorated buildings in any town and often housed a bar,

stage for entertainment, and hotel rooms for guests. These establishments

were a driving force behind the local economy and many towns measured their

prosperity by the number of gambling halls and professional gamblers they

had. Towns that were friendly to gaming were typically known to sports

as "wide-awake" or "wide-open" for their acceptance of gambling.

Most western citizens considered gambling to be a respectable

profession and those who chose to make a living doing it were respected

members of society. "Gambling was not only the principal and best paying

industry of the town at the time, but it was also reckoned among its most

respectable," wrote Bat Masterson in 1907 Professional gamblers ran their

own games by renting a table at a gambling house and banking it with their

own money. Because of this, many professional gamblers settled in one place

and in order to be successful as an established businessman, a gambler

needed cultivate a reputation for fairness and running a straight game.

These men were known as sports and did not drink, cheat, or swear, paid

rent and licensing fees, encouraged customers to run up bar tabs, and did

their best to act as historian Hubert Hoover Bancroft put it, "reputable

and respectable merchants." Bancroft distinguishes between three types

of professional gamblers, the free-floating professional, the established

legit, and the recreational gentleman.

The California Gold Rush of 1849 created one of the largest

draws for migrant gamblers, and San Francisco soon became the gambling

hotspot of the west. Famous gambling houses included the Parker House,

Samuel Dennison's Exchange, and the El Dorado Gambling Saloon. Portsmouth

Square was famous for the many houses that clustered closely around it.

Gambling was also popular in the many mining camps throughout California

and the southwest. Gambling was so closely associated with the Gold Rush

that the overland route to California that passed through Panama became

known as the "Gambler's Route." Dealers lay in wait everywhere, and it

is said that many an expedition to the gold fields ended in camp before

it even began. Mining towns outside of California developed large-scale

gambling as well. Deadwood, Silver City, and Tombstone were all as well

known for their many gambling halls and saloons as they were for their

rich mineral deposits.

Cattle towns in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska

became centers of gambling as well. Thanks to the railroad and cattle industries,

a great number of people worked in and around these towns and had plenty

of money to wager. Abilene, Dodge City, Wichita, Omaha, and Kansas City

all had an atmosphere that was convivial to gaming. Not surprisingly such

an atmosphere also invited trouble and such towns also developed reputations

as lawless and dangerous places.

Women gamblers

Men were not the only ones who played at games of chance,

women placed their bets as well and the sight of petticoats at the table

was normal. Many women played, dealt, or ran their own houses; this choice

of profession offered them the opportunity to attain monetary independence

and social stature. One of the most famous was Eleanore Dumont, known more

crudely in her later years as "Madame Mustache." Miss Dumont ran several

different houses throughout her career in Nevada, Idaho, Montana, and South

Dakota. Another, Alice Ives, started gambling after the death of her husband.

Known more popularly as Poker Alice, she was a popularly recognized figure

in the west for her nearly forty year long career. Kitty LeRoy made use

of her sex appeal and flamboyant personality as well as great gambling

ability to become a force of nature in Deadwood. She had multiple husbands

and did not hesitate to get rid of men once she tired of them. Perhaps

they were lucky because Kitty also had a reputation for shooting men as

well.

Race

Many nationalities and races were represented by frontier

gamblers. Especially in California during the gold rush, prospectors came

from all over the world in search of gold and naturally played games of

chance. This included Mexicans, Chinese, Australians, and Peruvians. Anglo

migrants to areas of the southwest with pre-established Mexican populations

discovered gambling there waiting for them. Most towns had at least one

or two salas, or, gambling houses. One of the most popular games, monte,

originated in Mexico and was adopted and later modified into three card

monte. The Chinese were avid gamblers who brought a variety of games with

them to North America, including Fan Tan and several different lottery

variants. Chinatown in San Francisco contained a great number of gaming

houses and was a popular destination for those seeking to play.

Games

Gamblers preferred fast-paced games allowed them an opportunity

to turn a profit quickly. Faro was the most popular game of the time and

was known as the king of all games. It was not the only game people played,

and monte, Vingt-et-Un (twenty-one), roulette, chuck-a-luck were all popular

ways to take a risk. Poker was not initially popular because of its slow

pace but gradually increased in popularity as time went on. Not all games

required playing cards; dice games such as craps were common as were games

involving a wheeled device, such as roulette or hazard. Saloons and gaming

tables were not the only places to bet however, and westerners had a well-deserved

reputation of being willing to bet on anything. Horse races became an enormously

popular means of wagering, and foot races and boxing matches provided a

similar opportunity. Fights between animals were popular as well, whether

cockfighting, dogfights, or even a panther vs. bear battle.

In popular culture

The popular stereotype of the frontier gambler presents

a tall, thin male wearing a mustache. He is well groomed and wears a tailored

suit, usually of black. Usually having a southern background, the frontier

gambler is presented as a gentlemen in manner and custom and is concerned

with maintaining his honor. The gambler possesses a calm demeanor and is

cool under pressure, but when crossed instantly becomes a cold-blooded

killer.

Gambling and gamblers are featured in many, many western

books, movies, and TV programs and this high occurrence reflects the ubiquity

of the activity in western society. The high frequency of these scenes

reveal the close association between the west and gambling that continues

today, an association just as strong as that of the west with cowboys or

lawmen. Gambling is a convenient plot device; it may be used in the background,

a setting for character discussion, or the motivation behind the plot.

For example, scenes depicting high-stakes card games or gunfights over

those games are so common as to be cliché.

The persistent presence of gambling in western mythology

shows a strong association with the risk-taking and chance that were involved

both in coming to the west and in everyday life there. In a sense, those

who chose to leave their lives and come west were taking a huge gamble

just to begin with. Gambling is also strongly associated with extralegal

activity and to have that activity practiced so frequently suggests a popular

association of the west with a state of lax legal and moral codes.

Notable figures and places

Bat Masterson

Charles Cora

Ben Thompsen

Doc Holliday

James McCabe

Luke Short

Poker Alice

Soapy Smith

Wild Bill Hickok

Wyatt Earp

Deadwood

Denver

Dodge City

San Francisco

Kansas City

|

Poker Alice from Wikipedia

| Alice Ivers Duffield Tubbs Huckert (1851–February 27,

1930), better known as Poker Alice or Poker Alice Ivers, was a famous poker

player in the American West.

Her family moved from Devon, England, where she was born,

to Virginia, United States, where she was reared and educated. As an adult,

Ivers moved to Leadville, Colorado, where she met her first husband, Frank

Duffield. He got Ivers interested in poker, but he was killed a few years

after they married. Ivers made a name for herself by winning money from

poker games in places like Silver City, New Mexico, and even working at

a saloon in Creede, Colorado, that was owned by Bob Ford, the man who killed

Jesse James.

Early life

“Poker” Alice Ivers was born in England, to Irish Immigrants.

Her family moved to Virginia when Alice was twelve. As a young woman, she

went to boarding school in Virginia to become a refined lady. While in

her late teens, her family moved to Leadville, a city in the then Colorado

Territory.

Personal life

It was in Leadville that Alice met Frank Duffield, whom

she married at a young age. Frank Duffield was a mining engineer who played

poker in his spare time. After just a few years of marriage, Duffield was

killed in an accident while resetting a dynamite charge in a Leadville

mine.

Ivers was known for splurging her winnings, as when she

won a lot of money in Silver City and spent it all in New York. After all

of her big wins, she would travel to New York and spend her money on clothes.

She was very keen on keeping up with the latest fashions and would buy

dresses to wear to play poker.

Alice met her next husband around 1890 when she was a

dealer in Bedrock Tom’s saloon in Deadwood, South Dakota. When a drunken

miner tried to attack her fellow dealer Warren G. Tubbs with a knife, Alice

threatened him with her .38. After this incident, Tubbs and Ivers started

a romance and were married soon after.

Alice Ivers and Warren Tubbs had four sons and three daughters

together. Tubbs and Ivers did not want their children to be influenced

by the world of poker, so they moved to a house just northeast of Sturgis

on the Moreau River in South Dakota. Tubbs was not only a dealer, but a

housepainter as well. It was most likely this house |

Alice Ivers Duffield Tubbs Huckert,

usually known as "Poker Alice" Tubbs

| Born |

February 17, 1851

Devonshire, England |

| Died |

February 27, 1930 (aged 79)

Rapid City, Pennington County

South Dakota, USA |

| Cause of death |

Failed gall bladder surgery |

| Resting place |

St. Aloysius Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota |

| Residence |

Sturgis, Meade County

South Dakota |

| Occupation |

Gambler; Brothel operator; Rancher |

| Religion |

Proclaimed Christian |

| Spouse(s) |

Three-time widow:

(1) Frank Duffield

(2) Warren G. Tubbs

(3) George Huckert |

| Children |

Seven children from second marriage |

|

painting that caused him to fall sick with tuberculosis.

Warren Tubbs died in 1910 of pneumonia during a blizzard. To pay for his

funeral, Alice had to pawn her wedding ring, which led her back to the

poker tables.

Alice’s third husband was George Huckert, who worked on

her homestead taking care of the sheep. Huckert was constantly proposing

to Ivers, yet for a while she did not agree. Eventually, however, Ivers

owed Huckert $1,008, so she married him figuring that it would be cheaper

than paying his back wages. Huckert died in 1913.

Poker career

After the death of her first husband, Alice started to

play poker seriously. Alice was in a tough financial position. After failing

in a few different jobs including teaching, she turned to poker to support

herself financially. Alice would make money by gambling and working as

a dealer. Ivers made a name for herself by winning money from poker games.

By the time Ivers was given the name “Poker Alice,” she was drawing in

large crowds to watch her play and men were constantly challenging her

to play. Saloon owners liked that Ivers was a respectable woman who kept

to her values. These values included her refusal to play poker on Sundays.

As her reputation grew, so did the amount of money she

was making. Some nights she would even make $6,000, an incredibly large

sum of money at the time. Alice claimed that she won $250,000, which would

now be worth more than three million dollars.

Ivers used her good looks to distract men at the poker

table. She always had the newest dresses, and even in her 50s was considered

a very attractive woman. She was also very good at counting cards and figuring

odds, which helped her at the table.

Alice was known to always be carrying a gun with her,

preferably her .38, and frequently smoked cigars.

Poker's Palace and Jailtime

In 1910, Ivers opened “Poker’s Palace,” a saloon in Fort

Meade, South Dakota, which offered gambling and liquor downstairs, and

prostitution upstairs. The saloon was always closed on Sundays because

of Ivers’ proclaimed religious beliefs. However, in 1913, some drunken

soldiers disobeyed Iver’s “no work on Sunday” rule and started to get unruly,

chaotic, and destructive of the house. It was then that Ivers shot her

gun, supposedly to quiet down the soldiers. The shot ended up killing one

of the soldiers and injuring another, resulting in Ivers' arrest, along

with the arrest of six of her prostitutes.

Ivers’ time spent in jail was short, but she got through

it with the help of reading the Bible and smoking cigars. At the trial,

she claimed self-defense and was acquitted. After the trial, her saloon

was shut down.

While in her sixties, Alice Ivers was arrested several

times after the “Poker Palace” incident for being a madam, a gambler, and

a bootlegger, as well as her drunkenness. She would comply with the law

and pay her fines but kept her business. In 1928, she was arrested again

for bootlegging and her repeated offenses of conducting a brothel. Despite

this sentence to prison, Ivers did not end up confined because she was

pardoned by then Governor William J. Bulow of South Dakota, who took this

action because of her old age.

Legacy

After being forced to retire by the anger of the military

and other people who were upset with her blend of religious elements at

her house in Sturgis, Alice’s health began to fail her. Alice Ivers died

on February 27, 1930 in Rapid City after a gall bladder operation at the

age of 79. Ivers was buried at the St. Aloysius Cemetery in Sturgis, South

Dakota.

Ivers has been fictionalized in several films and numerous

television series, including the 1978 TV-movie The New Maverick with James

Garner as Bret Maverick and Susan Sullivan as Poker Alice Ivers. The TV-movie

Poker Alice, in which the titular cigar-smoking and bordello-owning poker

player was portrayed by Elizabeth Taylor, was fictionalized to the point

that the character had a different last name.

|

Soapy Smith from Wikipedia

| Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith II (November 2, 1860

– July 8, 1898) was a famous con artist, saloon and gambling house proprietor,

gangster and crime boss of the nineteenth century old west. His most famous

scam, the prize package soap sell racket, presented him with the sobriquet

of "Soapy," which remained with him to his death. Although he traveled

and operated his confidence swindles all across the western United States

he is most famous for having a major hand in the organized criminal operations

of Denver, Colorado; Creede, Colorado; and Skagway, Alaska, from 1879 to

1898. In Denver he ran several saloons, gambling halls, cigar stores, and

auction houses that specialized in cheating its clientele. It was in Denver

that Soapy began to make a name for himself across the country as a bad

man. Denver is also where he entered into the arena of political fixing,

where, for favors, he could sway the outcome of city, county, and state

elections. He used the same methods of operation when he settled in the

towns of Creede and Skagway, opening businesses with the primary goal of

gently robbing his customers, while making a name for himself. He died

in spectacular fashion in the shootout on Juneau Wharf in Skagway, Alaska.

Early years

Jefferson Smith was born in Coweta County, Georgia, to

a family of education and wealth. His grandfather was a plantation owner

and his father a lawyer. The family met with financial ruin at the close

of the American Civil War. In 1876 they moved to Round Rock, Texas, to

start anew.

Smith left his home shortly after the death of his mother,

but not before witnessing the shooting of the outlaw Sam Bass. It was in

Fort Worth, Texas, that Jefferson Smith began his career as a confidence

man. He formed a close-knit, disciplined gang of shills and thieves to

work for him. Soon he became a well-known crime boss, the "king of the

frontier con men". |

| Born |

Jefferson Randolph Smith II

November 2, 1860

Coweta County, Georgia |

| Died |

July 8, 1898 (aged 37)

Skagway, Alaska |

| Occupation |

confidence man, gangster, gambler, and saloon proprietor |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary Eva Noonan |

| Children |

Jefferson Randolph Smith III, Mary Eva Smith, James Luther

Smith |

| Parents |

Jefferson Randolph Smith I

Emily Dawson Edmondson |

|

Career

Smith spent the next 22 years as a professional bunko

man and boss of an infamous gang of swindlers. They became known as the

Soap Gang, and included famous men such as Texas Jack Vermillion and "Big

Ed" Burns. The gang moved from town to town, plying their trade on their

unwary victims. Their principal method of separating victims from their

cash was the use of "short cons", swindles that were quick and needed little

setup and few helpers. The short cons included the shell game, three-card

monte, and any game in which they could cheat.

The Prize Package Soap Racket

Some time in the late 1870s or early 1880s, Smith began

duping entire crowds with a ploy the Denver newspapers dubbed "The prize

soap racket".

Smith would open his "tripe and keister" (display case

on a tripod) on a busy street corner. Piling ordinary soap cakes onto the

keister top, he began expounding on their wonders. As he spoke to the growing

crowd of curious onlookers, he would pull out his wallet and begin wrapping

paper money, ranging from one dollar up to one hundred dollars, around

a select few of the bars. He then finished each bar by wrapping plain paper

around it to hide the money.

He mixed the money-wrapped packages in with wrapped bars

containing no money. He then sold the soap to the crowd for one dollar

a cake. A shill planted in the crowd would buy a bar, tear it open, and

loudly proclaim that he had won some money, waving it around for all to

see. This performance had the desired effect of enticing the sale of the

packages. More often than not, victims bought several bars before the sale

was completed. Midway through the sale, Smith would announce that the hundred-dollar

bill yet remained in the pile, unpurchased. He then would auction off the

remaining soap bars to the highest bidders.

Through manipulation and sleight-of-hand, he hid the cakes

of soap wrapped with money and replaced them with packages holding no cash.

The only money "won" went to shills, members of the gang planted in the

crowd pretending to win in order to increase sales.

Smith quickly became known as "Soapy Smith" all across

the western United States. He used this swindle for twenty years with great

success. The soap sell, along with other scams, helped finance Soapy's

criminal operations by paying graft to police, judges, and politicians.

He was able to build three major criminal empires: the first in Denver,

Colorado (1886–1895); the second in Creede, Colorado (1892); and the third

in Skagway, Alaska (1897–1898).

Criminal boss of Denver, Colorado

In 1879 Smith moved to Denver and began to build the first

of his empires. Con men normally moved around to keep out of jail, but

as Smith's power and gang grew, so did his influence at City Hall, allowing

him to remain. By 1887 he was reputedly involved with most of the criminal

bunko activities in the city. Newspapers in Denver reported that he controlled

the city's criminals, underworld gambling and accused corrupt politicians

and the police chief of receiving his graft.

Tivoli Club

In 1888 Soapy opened the Tivoli Club, on the southeast

corner of Market and 17th streets, a saloon and gambling hall. Legend has

it that above the entrance was a sign that read caveat emptor, Latin for

"Let the buyer beware". Soapy's younger brother, Bascomb Smith, joined

the gang and operated a cigar store that was a "front" for dishonest poker

games and other swindles, operating in one of the back rooms. Other "businesses"

included fraudulent lottery shops, a "sure-thing" stock exchange, fake

watch and bogus diamond auctions, and the sale of stocks in nonexistent

businesses.

Politics and other cons

Because of his bribes, some of the police officers patrolling

the streets would not arrest Soapy or members of his gang. If they did,

a quick release from jail was arranged easily. A voting fraud trial after

the municipal elections of 1889 focused attention on corrupt ties and payoffs

between Soapy, the mayor, and the chief of police-a combination referred

to in local newspapers as "the firm of Londoner, Farley and Smith."

Smith opened an office in the prominent Chever block,

a block away from his Tivoli Club, from which he ran his many operations.

This also fronted as a business tycoon's office for high-end swindles.

Soapy was not without enemies and rivals for his position

as the underworld boss. He faced several attempts on his life and shot

several of his assailants. He became known increasingly for his gambling

and bad temper.

Creede, Colorado

In 1892, with Denver in the midst of anti-gambling and

saloon reforms, Smith sold the Tivoli and moved to Creede, Colorado, a

mining boomtown that had formed around a major silver strike. Using Denver-based

prostitutes to cozy up to property owners and convince them to sign over

leases, he acquired numerous lots along Creede's main street, renting them

to his associates. Once having gained enough allies, he announced that

he was the camp boss.

With brother-in-law and gang member William Sidney "Cap"

Light as deputy sheriff, Soapy began his second empire, opening a gambling

hall and saloon called the Orleans Club. He purchased and briefly exhibited

a petrified man nicknamed "McGinty" for an admission of 10 cents. While

customers were waiting in line to pay their dime, Soapy's shell and three-card

monte games were winning dollars out of their pockets.

Smith provided an order of sorts, protecting his friends

and associates from the town's council and expelling violent troublemakers.

Many of the influential newcomers were sent to meet him. Soapy grew rich

in the process, but again was known to give money away freely, using it

to build churches, help the poor, and to bury unfortunate prostitutes.

Creede's boom very quickly waned and the corrupt Denver

officials sent word that the reforms there were coming to an end. Soapy

took McGinty back to Denver. He left at the right time, as Creede soon

lost most of its business district in a huge fire on 5 June 1892. Amongst

the buildings lost was the Orleans Club.

Back to Denver

On his return to Denver, Smith opened new businesses that

were nothing more than fronts for his many short cons. One of these sold

discounted railroad tickets to various destinations. Potential purchasers

were told that the ticket agent was out of the office, but would soon return,

and then offered an even bigger discount by playing any of several rigged

games. Soapy's power grew to the point that he admitted to the press that

he was a con man and saw nothing wrong with it. In 1896 he told a newspaper

reporter, "I consider bunco steering more honorable than the life led by

the average politician."

Colorado's new governor Davis Hanson Waite, elected on

a Populist Party reform platform, fired three Denver officials who he felt

were not abiding by his new mandates. They refused to leave their positions

and were quickly joined by others who felt their jobs were threatened.

The governor called out the state militia to assist removing those fortified

in city hall. The military brought with them two cannons and two Gatling

guns. Soapy joined in with the corrupt officeholders and police at the

hall and found himself commissioned as a deputy sheriff. He and several

of his men climbed to the top of City Hall's central tower with rifles

and dynamite to fend off any attackers. Cooler heads prevailed, however,

and the struggle over corruption was fought in the courts, not on the streets.

Soapy Smith was an important witness in court.

Governor Waite agreed to withdraw the militia and allow

the Colorado Supreme Court to decide the case. The court ruled that the

governor had authority to replace the commissioners, but he was reprimanded

for bringing in the militia, in what became known as the "City Hall War".

Waite ordered the closure of all Denver's gambling dens,

saloons and bordellos. Soapy exploited the situation, using the recently

acquired deputy sheriff's commissions to perform fake arrests in his own

gambling houses, apprehending patrons who had lost large sums in rigged

poker games. The victims were happy to leave when the "officers" allowed

them to walk away from the crime scene rather than be arrested, naturally

without recouping their losses.

Eventually, Soapy and his brother Bascomb Smith became

too well known, and even the most corrupt city officials could no longer

protect them. Their influence and Denver-based empire began to crumble.

When they were charged with attempted murder for the beating of a saloon

manager, Bascomb was jailed, but Soapy managed to escape, becoming a wanted

man in Colorado. Lou Blonger and his brother Sam, rivals of the Soap Gang,

acquired his former control of Denver's criminals.

Before leaving, Soapy tried to perform a swindle started

in Mexico, where he tried to convince President Porfirio Diaz that his

country needed the services of a foreign legion made up of American toughs.

Soapy became known as Colonel Smith, and managed to organize a recruiting

office before the deal failed.

Skagway, Alaska, and the Klondike gold rush

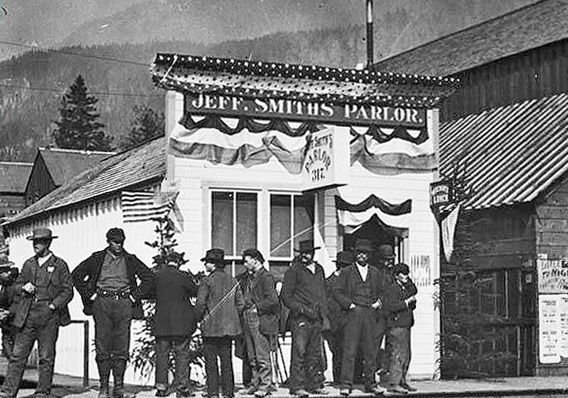

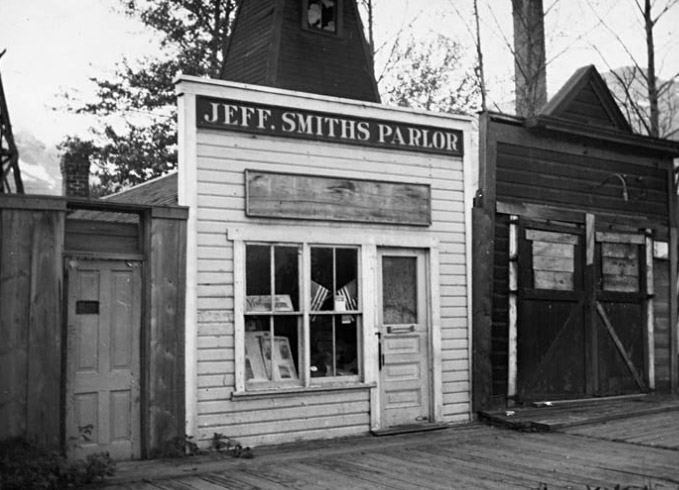

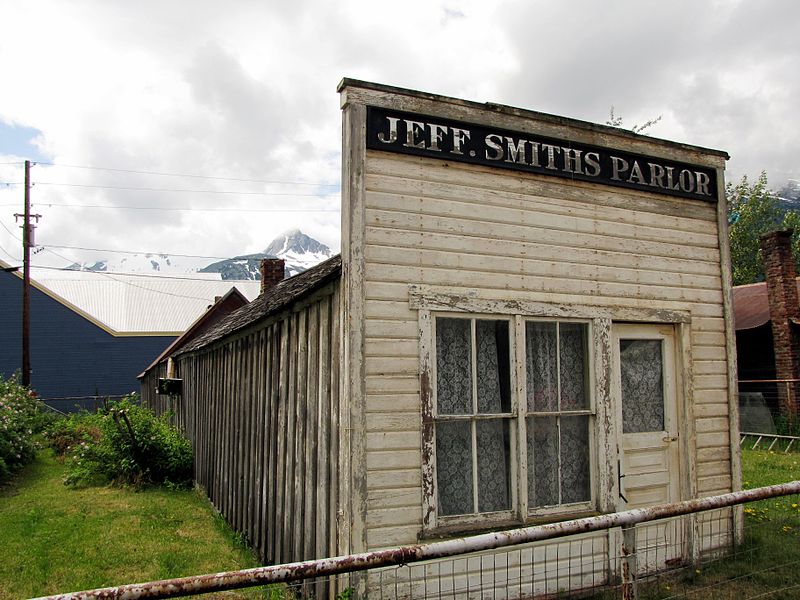

Jeff. Smiths Parlor, Soapy's base of operations

1898 Klondike gold rush |

1948 |

2009, before restoration |

|

|

When the Klondike Gold Rush began in 1897, Soapy moved his

operations to Dyea and Skagway, Alaska (then spelled Skaguay). His first

attempt at occupying Skaguay ended in failure when miners committees encouraged

him to leave the area after operating his 3-card monte and pea-and-shell

games on the White Pass Trail for less than a month. He traveled to St.

Louis and Washington, D. C., and did not return to Skagway until late January

1898.

Soapy set up his third empire much the same way as he

had in Denver and Creede. He put the town's deputy U.S. Marshal on his

payroll and began collecting allies for a takeover. Soapy opened a fake

telegraph office in which the wires went only as far as the wall. Not only

did the telegraph office obtain fees for "sending" messages, but cash-laden

victims soon found themselves losing even more money in poker games with

new found "friends". Telegraph lines did not reach or leave Skagway until

1901. Soapy opened a saloon named Jeff Smith's Parlor (opened in March

1898), as an office from which to run his operations. Although Skagway

already had a municipal building, Soapy's saloon became known as "the real

city hall." Skagway was gaining a reputation as a "hell on earth," with

many perils for the unwary.

Smith's men played a variety of roles, such as newspaper

reporter or clergyman, with the intention of befriending a new arrival

and determining the best way to rid him of his money. The new arrival would

be steered by his "friends" to dishonest shipping companies, hotels, or

gambling dens, until he was wiped out. If the man was likely to make trouble

or could not be recruited into the gang, Soapy himself would then appear

and offer to pay his way back to civilization.

When a vigilance committee the "Committee of 101", threatened

to expel Soapy and his gang, he formed his own "law and order society",

which claimed 317 members, to force the vigilantes into submission. Most

of the petty gamblers and con men did indeed leave Skagway at this time,

and Smith resorted to other means to appear respectable to the community.

During the Spanish-American War in 1898, Smith formed

his own volunteer army with the approval of the U.S. War Department. Known

as the "Skaguay Military Company," with Soapy as its captain. Smith wrote

to President William McKinley and gained official recognition for his company,

which he used to strengthen his control of the town.

On 4 July 1898, Soapy rode as marshal of the Fourth Division

of the parade leading his army on his gray horse. On the grandstand, he

sat beside the territorial governor and other officials.

Death

|

On 7 July 1898, John Douglas Stewart, a returning Klondike

miner, came to Skagway with a sack of gold valued at $2,700 ($78,870 in

2013 dollars.) Three gang members convinced the miner to participate in

a game of three-card monte. When Stewart balked at having to pay his losses,

the three men grabbed the sack and ran. The "Committee of 101" demanded

that Soapy return the gold, but he refused, claiming that Stewart had lost

it "fairly".

On the evening of 8 July 1898, the vigilance committee

organized a meeting on the Juneau wharf. With a Winchester rifle draped

over his shoulder, Soapy began an argument with Frank H. Reid, one of four

guards blocking his way to the wharf. A gunfight, known as the Shootout

on Juneau Wharf began unexpectedly, and both men were fatally wounded.

Soapy's last words were "My God, don't shoot!" A letter

from Samuel Steele, the |

head of the Canadian Mounties at the time, indicates that

another guard, Jesse Murphy, may have fired the fatal shot. Soapy died

on the spot with a bullet to the heart. He also received a bullet in his

left leg and a severe wound on the left arm by the elbow. Reid died 12

days later with a bullet in his leg and groin area. The three gang members

who robbed Stewart received jail sentences.

Soapy Smith was buried several yards outside the city

cemetery. Due to the way Smith's legend has grown, every year on 8 July,

wakes are held around the United States in Soapy's honor. His grave and

saloon are on most tour itineraries of Skagway.

Soapy Smith's grave (2009) |

Frank Reid's grave (2009) |

Soapy Smith's fame

Smith’s fame began in 1889 in Denver when he assaulted

editor John Arkins of the Denver Rocky Mountain News. The newspaper declared

war on Smith and the Soap Gang, sending articles and warnings about the

bunco gang all across the U.S. Smith's fame continued to grow right up

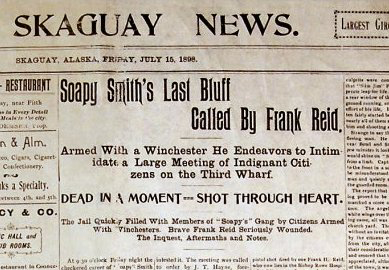

to, and beyond the day he died. The story told in the Skaguay News on July

9, 1898 and newspapers throughout the country was that one brave man had

sacrificed himself to slay a vicious con man - the con king of Skagway

– in order that Skagway could be freed of all crime.

By 1907, ten years after the founding of Skagway, aspiring

politician, Chris Shea, authored a booklet using photographs taken by Sinclair

and professional Skagway photographers Theodore Peiser and Case and Draper.

He called it, after a collage of photographs, The “Soapy” Smith Tragedy.

This booklet was the first book published on Smith.

By the 1950s Smith was sort of a Robin Hood figure, who

took from the miners and gave to the poor widows, orphans, dogs, and criminals

who lived by their wits. Smith, the anti-hero, was a loyal friend who stood

by his men, outwitted the stuffy reformers and conventional citizens and

lives on as the rascally King of the Con Men.

|

.

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|