| 6 Wild Women of the old west.

1. Lottie Deno - Wikipedia

Carlotta J. Thompkins, also known as Lottie Deno (April

21, 1844 – February 9, 1934), was a famous gambler in the U.S. state of

Texas during the 19th century known for her poker skills as well as her

courage.

| She was born in Kentucky and traveled a great deal in

her early adulthood before coming to Texas. Much of her earlier life and

even her real name at birth are a matter of debate among historians, but

her fame as a poker-player in the Southwest is not. According to author

Johnny Hughes, "In the late 1800s Texas' most famous poker player was Lottie

Deno (a shortened form of 'dinero' - Spanish for money)."

Early life

Carlotta J. Thompkins (her presumed real name) was born

on April 21, 1844 in Warsaw, Kentucky. Her family was reportedly quite

wealthy and her father, a racehorse breeder and prominent gambler, is said

to have traveled extensively with Lottie, teaching her the secrets of winning

at cards at some of the finest casinos. After her father's death in the

Civil War, Lottie's mother sent her to Detroit to find a husband. She was

accompanied by Mary Poindexter, her loyal slave and nanny. After running

out of money in Detroit, Thompkins fell into a life of gambling, traveling

the Mississippi River. Poindexter, reportedly seven-feet tall and formidable,

acted as Thompkins' protector during their travels.

Gambling days in Texas

Lottie arrived in San Antonio in 1865. She became a house

gambler at the University Club working for the Thurmond family from Georgia.

It was during this time that she met and fell in love with Frank Thurmond,

a fellow gambler.

|

|

After being accused of murder, Frank fled San Antonio and

Lottie followed. The pair traveled for many years throughout the frontier

areas of Texas, including Fort Concho, Jacksboro, San Angelo, Denison,

Fort Worth, and Fort Griffin. Their travels occurred during a local economic

boom on the Texas frontier as demand for bison hides spiked in the mid

and late 1870s. Cowboys and traders flush with cash during the period became

targets for gamblers in frontier communities. It was at Fort Griffin, where

Lottie lingered for some time, that her notoriety and legend became most

established. Fort Griffin, which was a frontier outpost west of Fort Worth

near the Texas Panhandle, was known for its saloons and the rough element

it attracted. Gaining fame as a gambler Lottie became associated with various

old west personalities, including Doc Holliday.

During her travels she gained numerous nicknames. In San

Antonio she was known as the "Angel of San Antonio." At Fort Concho she

became known as "Mystic Maud." At Fort Griffin she was called "Queen of

the Pasteboards" and "Lottie Deno." It was this last moniker by which she

became best known. Her escapades during this period became part of the

folklore of the American Wild West.

Later life

Lottie and Frank moved to Kingston, New Mexico, in 1877,

where they ran a gambling room in the Victorio Hotel. Lottie later became

the owner of the Broadway Restaurant in Silver City.

In 1880, Lottie and Frank were married in Silver City.

In 1882 they moved to Deming, New Mexico, where they settled permanently

and gave up their gambling life. They became upstanding citizens in the

community, with Frank eventually becoming vice president of Deming National

Bank and Lottie helping to found St. Luke's Episcopal Church. Lottie died

on February 9, 1934 and was buried in Deming as Charlotte Thurmond.

Legacy

Miss Kitty Russell, a character from the long running

American radio and television show Gunsmoke is based on Lottie Deno.

|

2. Baby Doe Tabor - Wikipedia

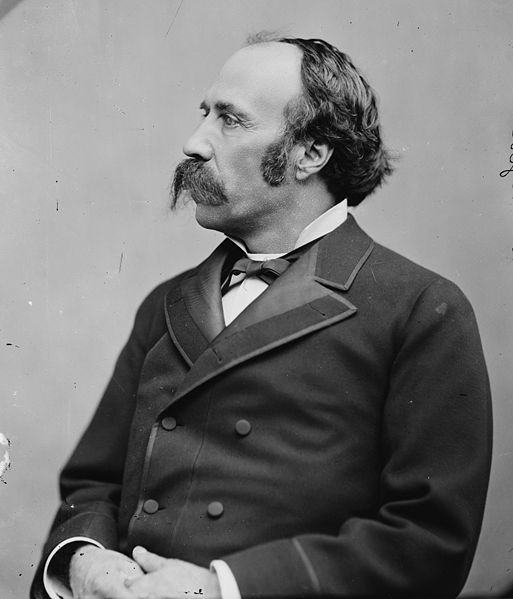

| Elizabeth McCourt Tabor (1854 – March 7, 1935), better

known as Baby Doe, was the second wife of pioneer Colorado businessman

Horace Tabor. Her rags-to-riches and back again story made her a well-known

figure in her own day, and inspired an opera and a Hollywood movie based

on her life.

Born in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, she moved to Colorado in the

mid-1870s with her first husband, Harvey Doe, whom she divorced for drinking,

gambling, frequenting brothels, and being unable to provide a living.

She then moved to Leadville, Colorado, where she met Tabor,

a wealthy silver magnate almost twice her age. In 1883 he divorced his

first wife, to whom he had been married for 25 years, and married Baby

Doe in Washington, D.C. during his brief stint as a US senator, after which

they took up residence in Denver. His divorce and remarriage to the young

and beautiful Baby Doe caused a scandal in 1880s Colorado. Although Tabor

was one of the wealthiest men in Colorado, supporting his wife in a lavish

style, he lost his fortune when the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase

Act caused the Panic of 1893 with widespread bankruptcies in silver-producing

regions such as Colorado. He died destitute, and she returned to Leadville

with her two daughters, living out the rest of her life there.

At one time the "best dressed woman in the West", for

the final three decades of her life, she lived in a shack on the site of

the Matchless Mine, enduring great poverty, solitude, and repentance. After

a snowstorm in March 1935, she was found frozen in her cabin, aged about

81 years. During her lifetime she became the subject of malicious gossip

and scandal, defied Victorian gender values, and gained a "reputation of

one of the most beautiful, flamboyant, and alluring women in the mining

West". Her story inspired the opera The Ballad of Baby Doe.

|

1883 |

Early life and marriage

Elizabeth Bonduel McCourt (or according to some accounts

Elizabeth Nellis McCourt) was born in 1854 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin to Irish-Catholic

immigrants Peter and Elizabeth McCourt. She later claimed to have been

born in 1860. She appears to have been christened on October 7, 1854 at

St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church. Called Lizzie as a child, the fourth

of eleven children, she grew up in a middle-class family in a two-story

house. Her father was a partner in a local clothing store and owner of

Oshkosh's first theater, McCourt Hall. Her mother fostered in her beautiful

daughter the belief that her looks were of great worth, excusing her from

domestic chores so as to preserve her skin and allowing her to dream of

a future as an actress. Concerned by his wife's indulgence in their young

and striking daughter, Peter McCourt thought it prudent to put her to work

at the clothing store, where she was often in the company of fashionable

young men. At age 16, she was a "fashionably plump" blond-haired young

woman with a hectic social schedule.

Oshkosh was a frontier lumber town, filled with mills.

When fires raged through Oshkosh in 1874 and again in 1875, the McCourts

lost their home, the clothing store, and the theater. They mortgaged their

property to rebuild the home and the business, but this put Peter McCourt

deeply in debt. The family was forced to live on what amounted to little

more than a clerk's salary.

In 1876, Lizzie McCourt met Harvey Doe, who was a Protestant.

She enchanted him when, as the only woman competitor, she entered and won

a skating competition, while at same time scandalizing many of the townspeople

by wearing a costume that showed glimpses of her legs. Lizzy and Harvey

were married in 1877 at the Catholic church, to the dissatisfaction of

his parents. They then traveled with Harvey's father to Colorado to look

after his mining investments, most importantly his half-ownership of the

Fourth of July Mine in Central City. After a two-week honeymoon in Denver's

American House, the newlyweds joined the elder Doe in the mining town in

the mountains. Lizzie found Colorado enchanting. There she may have gained

the nickname “Baby Doe”.

Move to Colorado

In Central City, she quickly found that her husband's

reserved temperament was unsuitable for a boisterous frontier mining town,

and that he was unable either to manage a mine on his own or to follow

his father's instructions on how to do so. Rather than see him fail, and

enchanted with the possibility of becoming wealthy from mining gold, she

helped her husband. She often dressed in mining clothes and worked directly

in the mine. Despite a somewhat relaxed culture in the frontier mining

town, those in the highest strata of the city's society considered her

behavior and dress scandalous, causing her to be ignored. Through both

their efforts, the Does did manage to bring up a small amount of gold,

but when the vein ran out and a poorly constructed shaft collapsed, Harvey

gave up and decided to take a job as a common mucker at another mine. He

told his wife to stop wearing men's clothing and stay at home.

At that time, they moved from Central City to Black

Hawk to live in a less expensive rooming house. Greatly disappointed and

disenchanted by the noise and dirt in Black Hawk, Baby Doe began to take

walks around the city each day. Then aged 23, she may have gained the name

"Baby Doe" from the local men watching. She lacked domestic skills with

which to work and earn money, and she had nothing in common with the women

of the town. Often, having little to do with her time, she visited the

local clothing store, attracted in part by the expensive fabrics. She became

friendly with the owner of the town's clothing store, Jake Sandelowsky.

At the same time Harvey lost his job, and their marriage began to deteriorate.

By that time Baby Doe was pregnant. Suspecting the child was Jake's, Harvey

left her temporarily, and in July 1879, Baby Doe gave birth to a stillborn

boy.

Meanwhile, Harvey's parents, expecting a grandchild, had

moved to Colorado to be near the family. Disappointed, they severed their

ties with the two and moved to Idaho Springs, while Baby Doe followed Harvey

to Denver despite wishing for a divorce from him. In Denver, Harvey frequented

saloons and brothels. After witnessing him with a prostitute, Baby Doe

filed for divorce on the grounds of adultery. The divorce was quickly granted

in March 1880, but for unknown reasons was not officially recorded until

April 1886. Baby Doe then moved to Leadville, Colorado, almost certainly

invited there by Sandelowsky, who changed his name to Sands. Alone and

without a husband, Baby Doe needed to find a means of financial support

quickly. Jake Sandelowsky, who opened a store in Leadville and almost certainly

wanted to marry her, offered her employment. Working at a clothing store,

however, was a prospect Baby Doe found dull, boring, and too similar to

the life she had left behind in Oshkosh.

Leadville

In Leadville, she caught the attention of Horace Tabor,

mining millionaire and owner of Leadville's Matchless Mine. Tabor was married,

but in 1880 he left his wife Augusta to be with Baby Doe; he established

her in plush suites at hotels in Leadville and Denver.

Horace and Augusta Tabor had lived for 25 years

on the frontier, first moving to Kansas where they tried their hand at

agriculture, then following the gold rush to Colorado, but never striking

it rich. Eventually they found their way to Leadville, where Horace, in

1878, grub-staked two prospectors with about $60 worth of goods in return

for one-third of their profits. To everyone's surprise, the two men's stake

was successful, beginning Tabor's path to wealth. With his profits, he

bought out the two, then bought stakes in more mines, and had a house built

in Denver. He ran successfully for Lieutenant Governor of Colorado in 1878,

(when still a territory), and established the Little Pittsburg Consolidated

Mining Company, which quickly gained a worth of about $20 million. He bought

the Matchless Mine, which for many years produced large amounts of silver.

His profits were so great that he was quickly on his way to becoming one

of the richest men in the country.

At an altitude of 10,000 feet, Leadville was the second

largest city in Colorado. It boasted over 100 saloons and gambling places,

multiple daily and weekly newspapers, and 36 brothels. Tabor's presence

seemed to be everywhere. He opened the Tabor Opera House in Leadville,

bought luxury items for his wife, Augusta, and established a private army

that he used for protection of his holdings and as a force against striking

miners. He spent his money lavishly, mostly on his own entertainment—drinking,

gambling and frequenting brothels. In 1880, Augusta moved away from him

to live in Denver while Tabor enjoyed himself in Leadville. A Denver newspaper

columnist described him as "Stoop-shouldered; ambling gait ...black hair,

inclined to baldness ....dresses in black; magnificent cuff buttons of

diamonds and onyx ...worth 8 million dollars." Historian Judy Nolte Temple

writes that it "seemed inevitable that the prettiest woman in the mining

West would eventually meet the richest man."

Baby Doe met Horace Tabor in a restaurant in Leadville

one evening in 1880. She told him her story and that she had arrived in

Leadville because of Jake Sandelowsky's generosity. Tabor gave her $5000

on the spot. Baby Doe then had a message, and $1000, delivered to Sandelowsky,

in which she declared that she would not marry him. Instead, Tabor moved

her to the Clarendon Hotel, next to the opera house and Sandelowsky's store,

Sands, Pelton & Company. Sandelowsky later moved to Aspen, where he

opened another store, married, and built a house.

Some months later, Tabor moved Baby Doe to the Windsor

Hotel in Denver. A newly constructed turreted building, meant to look like

Windsor castle, the hotel had extremely lavish decorations such as mirrors

made of diamond dust. Tabor had a gold-leafed bath-tub in his suite. Guests

were wealthy, well-known and well-connected.

Baby Doe claimed to love Tabor, and he loved her. He moved

permanently out of his Denver home and asked his wife Augusta for a divorce.

She refused him. He, in turn, refused to send her an invitation to attend

the grand opening of Denver's Tabor Grand Opera House. He stopped giving

his wife money; she sued him but failed; he again demanded a divorce. Baby

Doe suggested that he seek a divorce in a different jurisdiction, and in

1882 a Durango, Colorado, judge granted them a divorce. However, the filing

was irregular, and once Tabor realized that, he had the county clerk paste

together two pages in the records to hide the action. Despite his existing

marriage to Augusta, Horace Tabor and Elizabeth McCourt Doe married secretly

in St. Louis, Missouri, in September 1882. At that time both were bigamists:

his divorce was questionable and hers was not yet recorded.

Marriage to Horace Tabor

| In January 1883, Augusta sued Tabor again, and now he

compensated her with real estate in Denver and stock in his mines. Tabor

finally obtained a legal divorce at that time. That same month, the Colorado

State Legislature appointed him to a 30-day term as United States Senator

to fill a temporary vacancy because the sitting senator, Henry Teller,

had been appointed a cabinet member. Baby Doe and Horace married publicly

on 1 March 1883, just two months after Tabor and Augusta had divorced.

He was 52 and she 28, and she claimed to be only 22. The marriage took

place during Tabor’s brief tenure as a US senator, at the Willard Hotel

in Washington, DC. Baby Doe invited President Chester A. Arthur and other

dignitaries who attended, as reported by the media at the time of her death,

though a more recent biography claims many invitations were declined.

She planned a lavish wedding, going first to Oshkosh,

making arrangements for her family to attend the event, and purchasing

clothing and jewelry for them. Her mother was proud that her daughter was

marrying a wealthy man, and Baby Doe herself was quite happy. At her wedding

in Washington, she wore a white satin dress that cost $7,000 and the $90,000

necklace known as the "Isabella" necklace. Two days after the wedding,

the priest who had performed the ceremony refused to sign the marriage

license when he learned that both the bride and the groom had previously

divorced and that Baby Doe was a Roman Catholic. Although Tabor’s contemporaries

had winked at or ignored his dalliance with Baby Doe, Tabor’s divorce and

quick remarriage created a scandal which prevented the couple from being

accepted in polite society. Only a few months later, Horace's bid to be

elected governor of Colorado ended in failure. Baby Doe's father died at

around the same time.

|

|

The couple returned to Colorado, where they took up permanent

residence in a Denver mansion. Baby Doe was snubbed by Denver socialites,

from whom she received neither visits nor invitations. Although she did

not join charities or clubs, as was customary during that period for wealthy

women, she was generous with her money, donating funds to various charities,

and providing free offices to the Colorado suffragette movement. To keep

herself busy, she shopped, bought jewelry and clothing, had her hair done

and continued with the hobby of scrapbooking she had taken up when living

in Central City.

On July 13, 1884, she gave birth to the first of her and

Tabor's two daughters, Elizabeth Bonduel Lily Tabor. The infant was christened

in an extravagant and frilly outfit costing $15,000. Baby Doe was reportedly

a good mother, staying at home with her daughter instead of accompanying

Horace on his frequent trips to look after widespread business interests.

Their second daughter, Rose Mary Echo Silver Dollar Tabor, was born on

December 17, 1889. Both girls were attractive and well looked-after, and

their mother doted on them. The second child was fondly called Silver or

Silver Dollar, whom Baby Doe "defiantly nursed ... as she rode through

the streets in Denver in one of her carriages."

A year after the birth of their second child, in 1890,

the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was enacted, which brought to Colorado,

and Colorado mine-owners, the hope that wildly fluctuating silver prices

would stabilize. Profits from silver mining had diminished as the supply

had declined and the extraction process and labor costs had increased.

When a few of Horace's investments began to fail, he was forced to mortgage

the Tabor theater in Denver and other real estate he had bought during

the past decades.

Horace Tabor lost his fortune in 1893 when the repeal

of the Silver Act caused the Panic of 1893. Silver prices plummeted and

fortunes in Colorado were instantly wiped out. As she had with her first

husband, Baby Doe pitched in. Horace gave her the legal power to run his

business concerns in Denver, and she made decisions for him during his

absences. To raise money, she sold most of her jewelry, and when the couple

had the power turned off in their mansion, she made a game of it for the

children. Eventually, the mansion and its contents were sold. At age 65,

to earn a living, Horace took a job as a common mineworker, while the family

lived in a boarding house. From 1893 to 1898, the Tabors endured great

poverty, although some friends lent them money. To save him from poverty,

some political friends arranged his appointment as postmaster of Denver

in 1898. The family at that time lived on his annual salary of $3700 per

year and took up residence in a plain room at the Windsor Hotel. Horace's

health soon gave out, and 15 months after his appointment to the position,

he died.

His funeral was well attended, with perhaps as many as

10,000 there. On his deathbed he is said to have told Baby Doe to "hold

on the Matchless mine … it will make millions again when silver comes back."

However, that story might not be true; by then, it appears they had mortgaged

and/or lost the Matchless mine. At the time of her husband's death, Baby

Doe was still an attractive woman in her mid-forties.

Later years

The Matchless mine

After her husband's death, Baby Doe stayed in Denver for

a period, according to her diaries and correspondence. Why she decided

to leave Denver and the society there to make a return to Leadville, in

the high mountains with its cold winters, is unknown, but it almost certainly

had to do with the Matchless mine. For two years she unsuccessfully tried

to find investors to bring the Matchless back into production. The family

may have tried to regain ownership to the Matchless mine, but documentation

is fragmented, and it is unclear to whom the mine belonged at that time.

In 1901, one of her McCourt sisters may have attempted to buy the mine

at a sheriff's sale, but again the fragmented documentation is murky about

ownership. When Baby Doe moved with her girls back to Leadville, she claimed

she would work the mine herself, despite its deteriorated condition. Temple

writes that the mine's shafts were flooded and had not been in working

condition for many years, and furthermore that Horace would have known

this. To earn money, she took on menial domestic jobs. Unknown to

her, her brother paid the grocer so that the three women had food. Eventually,

in an attempt to keep the decrepit mine going and to raise funds, she reluctantly

sold the "Isabella necklace" Tabor had given her, but during her lifetime

she refused to sell his gold watch fob.

Her older daughter, Lily, left her mother to live with

Baby Doe’s family in Wisconsin. Later, after her mother died, Lily denied

being Baby Doe’s daughter. Of the two daughters, Lily, born into wealth,

seemed more affected by the fall into poverty. When in 1902, Baby Doe traveled

with her daughters to Oshkosh to visit her relatives, Lily decided then

to prolong her visit, to stay and provide care for her elderly grandmother.

Later, Lily moved to Chicago, where in 1908 she married her first cousin,

and soon after gave birth to Baby Doe's grandchild. In 1911, Baby Doe and

Silver again visited relatives in Wisconsin, going on to visit Lily in

Chicago. After such a prolonged absence, Lily claimed she barely knew Silver

Dollar.

After Lily's departure, Baby Doe and Silver Dollar moved

into a cabin on the site of the Matchless mine. The living quarters were

basic and inadequate for Colorado winters: "All told, it was no larger

than a medium sized room. Two windows had been cut into the flimsy weatherboards,

but these had been nailed up". The structure was a former tool shed located

adjacent to the hoisthouse, described by a visitor in 1927 as "crowded

with very primitive furniture, decorated with religious pictures, and stacked

high in newspapers." The cabin was isolated, located above Leadville in

Little Strayhorse Gulch, and had an unimpeded view of Mount Elbert and

Mount Massive.

Silver Dollar also left Leadville, soon after she had

turned to drink and had became sexually precocious. Worried, Baby Doe was

happy to send her away to Denver. There, Silver Dollar wrote for the Denver

Times, sending part of her earnings to her mother on a weekly basis. She

then attempted to become a novelist, while at the same time gaining a bad

reputation in Denver for her drunken antics. Perhaps to escape Colorado,

she moved to Chicago where again she tried her hand at writing. Eventually,

after working as a dancer under various names, she became the mistress

of a Chicago gangster. In 1925, Silver Dollar was found scalded to death

under suspicious circumstances in her Chicago boarding house, where she

had been living under the name "Ruth Norman". For the rest of her life,

Baby Doe refused to believe the woman found as Ruth Norman had been her

daughter, stating, "I did not see the body they said was my little girl."

Alone in the cabin outside Leadville, Baby Doe turned

to religion. She considered her life of great wealth a period of vanity

and created penances for herself. During the frigidly bitter Colorado high-country

winters, she wound burlap sacks around her legs. With no money, she ate

very little, living on stale bread and suet, and refused to accept charity.

Baby Doe lived like this for 35 years. During these years she wrote incessantly.

In diaries, letters, and scraps she called "Dreams and Visions", consisting

of about 2000 fragments later found bundled in piles of paper in her cabin,

she wrote entries such as: "Nov. 26—1918 Papa Tabor's Birthday I owe my

room rent & am in need of food and only enough bread for tonight &

breakfast .... my shoes and stockings only 1 pair are in rags." An eyewitness

described her in 1927 as dressed "in corduroy trousers, mining boots, and

a torn soiled blouse .... [with] a blue bandana tied around her head",

and went on to say that "her eyes were very far apart and a gorgeous blue".

She wandered the streets of Leadville, rags on her feet,

wearing a cross, and came to be known as a madwoman. Some who had been

acquainted with her earlier thought she deserved to suffer for having broken

up the marriage between Horace and Augusta, and believed that she had been

the cause of his ruin. At that time, Leadville had lost much of its boomtown

population and was becoming a ghost-town. She often walked the empty streets

at night, dressed in a mixture of women's and men's clothing, wearing trousers

and mining boots. She protected the mine from strangers with a shot-gun,

and "she became a sad spectre of Baby Doe to old-timers; a spectacle to

the young."

Death

In the winter of 1935, after an unusually severe snowstorm,

some neighbors noticed that no smoke was coming out of the chimney at the

Matchless mine cabin. Investigating, they found Baby Doe dead, her body

frozen on the floor. The Rocky Mountain News reported that a miner and

friend, concerned at not seeing her for some days, broke into the cabin

and found the body. The newspaper went on to compare her to another female

Leadville resident, Molly Brown. For one last time, Baby Doe made the front

pages of the papers. The interment had to be postponed because the ground

in Leadville at that time of year was "still frozen five feet deep". While

a gravesite was being prepared in Leadville—the ground had to be dynamited—wealthy

Denverites raised money to have her body brought there. A funeral mass

was held in Leadville, then her casket was sent by train to Denver. She

was apparently 81 years old at the time of her death.

Her remaining possessions were auctioned off to souvenir

collectors for $700. Baby Doe Tabor is buried with her husband in Mt. Olivet

Cemetery in Wheat Ridge, Colorado.

Reputation and legacy

Baby Doe Tabor is a legend among the women of the mining

West. She holds the reputation of being a great beauty, a home-wrecker,

and in her later years, a madwoman. Judy Nolte Temple writes that Baby

Doe's legend, and her sins, grew quickly in retelling, as evidenced by

an exaggerated description of her death in an early biography: "The formerly

beautiful and glamorous Baby Doe Tabor ... was found dead on her cabin

floor .... only partially clothed ....frozen into the shape of a cross".

She was rumored to be a gold-digger and a poor mother. Scavengers searched

for non-existent treasure after her death, but Temple says the real treasure

was found in Baby Doe's writing, which has taken decades to archive, analyze

and study, and only now is beginning to reveal the inner life of the woman.

Temple sees her as one in a long line of women who endured shunning and

punishment for her beauty and for being disruptive to prevailing social

norms. Temple speculates that Baby Doe's move to Leadville after Horace's

death may have been self-shunning from Denver society.

Baby Doe was portrayed in the Warner Brothers film Silver

Dollar, which premiered in Denver in 1932. "Lily", the fictionalized character

of Baby Doe, was portrayed by actress Bebe Daniels; Edward G. Robinson

played Yates Martin, a fictionalized Horace Tabor. Douglas Moore's opera

The Ballad of Baby Doe premiered in Central City, Colorado, in 1956. In

the New York premiere in 1958, Baby Doe was sung by Beverly Sills. In the

1970s, a string of western-themed "Baby Doe's Matchless Mine" restaurants

was established in a number of US cities. Almost all are now closed.

|

| 3. Fannie Porter - from Wikipedia

Fannie Porter (February 12, 1873 - c.1940) was a well

known madam of the 19th century. She was best known for her association

with famous outlaws of the day, and for her popular brothel.

| Career as a madam

Porter was born in England, and traveled to America around

the age of one with her family. By fifteen she was working as a prostitute

in San Antonio, Texas. By the age of 20, she had started her own brothel,

and became extremely popular for her cordial and sincere attitude, her

choosing only the most attractive young women as her "girls", her requirement

that her "girls" practice good hygiene, and for her always immaculate personal

appearance. Her brothel was located at the corner of Durango and San Saba

streets.

By 1895, her brothel in San Antonio was one of the most

popular of the Old West. It had by that time become known as a frequent

stop off for outlaws on the run from the law. Butch Cassidy, the Sundance

Kid, Kid Curry, and other members of the Wild Bunch gang frequented her

business. One of her "girls", Della Moore, became the girlfriend to Kid

Curry, remaining with him until her arrest for passing money from one of

his robberies. She was arrested, but acquitted, eventually returning to

work for Porter once again. Another of her "girls", Lillie Davis, became

involved with outlaw and Wild Bunch member Will "News" Carver. She later

claimed she had married Carver in Fort Worth prior to his death in 1901,

but there are no records to verify the alleged marriage. It is possible

that the Sundance Kid and his girlfriend Etta Place, whose true identity

and eventual disappearance from history has long been a mystery, first

met while she worked for Porter, but that has never been confirmed. Wild

Bunch gang member Laura Bullion is also believed to have at times worked

for Porter between the years of 1898 and 1901.

Porter was well respected for her discretion, always refusing

to turn in a wanted outlaw to the authorities. She also was known for being

extremely defensive of her "girls", insisting that any who mistreated them

never return to her brothel. She generally employed anywhere from five

to eight girls, all ranging in age from 18 to 25, and all of whom lived

and worked inside her brothel. Her business was not only popular with outlaws

of the day, but also with lawmen, and she made sure that any lawmen who

entered received the best treatment. William Pinkerton, of the Pinkerton

National Detective Agency, was said to have frequented her brothel.

By the early 20th century, the tide had begun to turn

against active, openly operating brothels. Eventually, she retired, and

faded from history. It is not known where she went following her retirement.

Most agree that she retired semi-wealthy, but it is unknown where she might

have gone. Some stories indicate that she married a man of wealth, some

indicate she retired into seclusion, while others indicate she returned

to England. None of those are confirmed. Later rumors indicated that she

lived until 1940, when she was killed in a car accident in El Paso, Texas.

However, that also is not certain. |

|

|

4. Charley Parkhurst - from Wikipedia

| Charley Darkey Parkhurst, born Charlotte Darkey Parkhurst

(1812–1879), also known as One Eyed Charley or Six-Horse Charley, was an

American stagecoach driver, farmer and rancher in California. Born and

reared as a girl in New England, mostly in an orphanage, Parkhurst ran

away as a youth, taking the name Charley and living as a male. He started

work as a stable hand and learned to handle horses, including to drive

coaches drawn by multiple horses. He worked in Massachusetts and Rhode

Island, traveling to Georgia for associated work.

In his late 30s, Parkhurst sailed to California following

the Gold Rush in 1849; there he became a noted stagecoach driver. In 1868

he may have been the first female (though passing as a man) to vote in

a presidential election in California. At his death, it was discovered

that his gender assigned at birth was female, as was the fact that he had

given birth at an earlier time

Life and career

Charley Parkhurst was born Charlotte Darkey Parkhurst

in 1812 in Sharon, Vermont, to Mary (Morehouse) Parkhurst and an unknown

father. Some reports say the father's first name was Charles. Parkhurst

had two siblings, Charles D. and Maria. Charles D. was born in 1811 and

died in 1813. The mother Mary died in 1812. Some time after Charley D.

died, Charlotte and Maria were taken to an orphanage in Lebanon, New Hampshire.

(Some sources say she was born there.) They were raised under the care

of Mr. Millshark. |

|

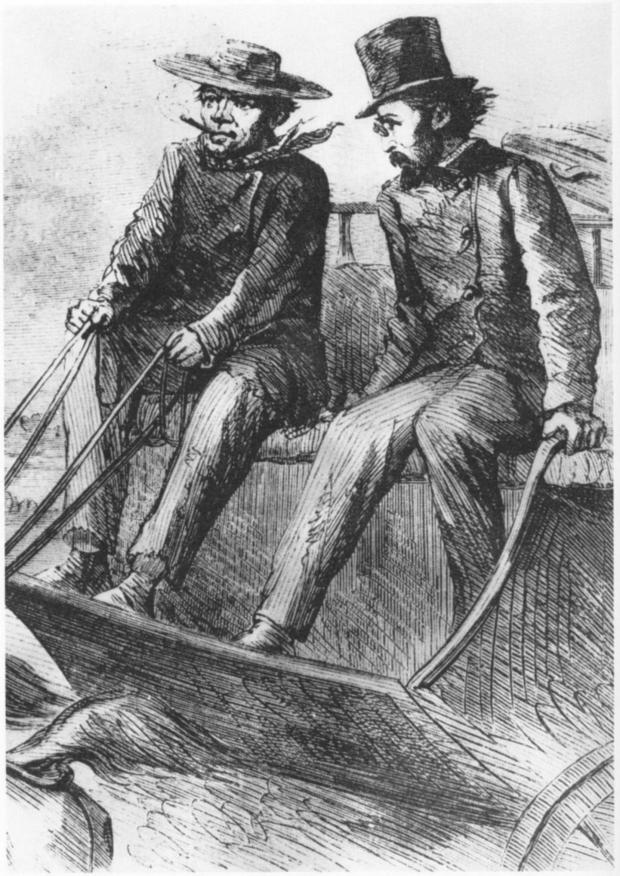

Parkhurst ran away from the orphanage at age 12. She adopted

the name Charley and assumed a more masculine self-presentation reflecting

his gender identity. According to one account, Parkhurst soon met Ebenezer

Balch, who had a livery stable in Providence, Rhode Island. He took what

he thought was an orphaned boy under his care and returned to Rhode Island.

Treating Parkhurst like a son, Balch taught him to work as a stable hand

and gradually with the horses. The boy developed an aptitude with horses,

and Balch taught him to drive a coach, first with one, then four, and eventually

six horses. Parkhurst worked for Balch for several years. He may have gotten

to know James E. Birch, who was a younger stagecoach driver in Providence.

In 1848, the 21-year-old James E. Birch and his close

friend Frank Stevens went to California during the Gold Rush to seek their

fortunes. Birch soon began a stagecoach service, starting as a driver with

one wagon. He gradually consolidated several small stage lines into the

California Stage Company.

Seeking other opportunities in California, Parkhurst in

his late 30s also left Rhode Island, sailing on the R.B. Forbes from Boston

to Panama; travelers had to cross the isthmus overland and pick up other

ships on the west coast. In Panama, Parkhurst met John Morton, returning

to San Francisco where he owned a drayage business; Morton recruited the

driver to work for him. Shortly after reaching California, Parkhurst lost

the use of one eye after a kick from a horse, leading to his nickname of

One Eyed Charley or Cockeyed Charley.

Later Parkhurst went to work for Birch, where he developed

a reputation as one of the finest stage coach drivers (a "whip") on the

West Coast. This inspired another nickname for him, Six-Horse Charley.

He was ranked with "Foss, Hank Monk and George Gordon" as one of the top

drivers of his time. Stagecoach drivers were also nicknamed "Jehus," after

a Biblical passage in Kings 9:20: “…and the driving is like the driving

of Jehu the son of Nimshi; for he driveth furiously.”

Among Parkhurst's routes in northern California were Stockton

to Mariposa, "the great stage route" from San Jose to Oakland, and San

Juan to Santa Cruz. Stagecoach drivers carried mail as well as passengers,

and had to deal with hold-up attempts, bad weather, and perilous, primitive

trails. As historian Charles Outland described the era, "It was a dangerous

era in a dangerous country, where dangerous conditions were the norm."

Seeing that railroads were cutting into the stagecoach

business, Parkhurst retired from driving some years later to Watsonville,

California. For fifteen years he worked at farming, doing lumbering in

the winter. He also raised chickens in Aptos.

He later moved into a small cabin about 6 miles from Watsonville

and suffered from rheumatism in his later years. Parkhurst died there on

December 18, 1879, due to tongue cancer.

Posthumous revelation

After Parkhurst died in 1879, neighbors came to the cabin

to lay out the body for burial and discovered that his body appeared to

be female to them. Rheumatism and cancer of the tongue were listed as causes

of death. In addition, the examining doctor established that Parkhurst

had given birth at some time. A trunk in the house contained a baby's dress.

"The discovery of her true [sic] gender became a local sensation." and

was soon carried by national newspapers.

The obituary about Parkhurst from the San Francisco Call

was reprinted in The New York Times on 9 January 1880, so the extraordinary

driving career and the post-mortem discovery of Parkhurst's "true gender"

received national coverage. The headline was: "Thirty Years in Disguise:

A Noted Old Californian Stage-Driver Discovered. After Death. To be a Woman."

He was in his day one of the most dexterous

and celebrated of the famous California drivers ranking with Foss, Hank

Monk, and George Gordon, and it was an honor to be striven for to occupy

the spare end of the driver's seat when the fearless Charley Parkhurst

held the reins of a four-or six-in hand...

{{Last Sunday [December 28, 1879],

in a little cabin on the Moss Ranch, about six miles from Watsonville,

Charley Parkhurst, the famous coachman, the fearless fighter, the industrious

farmer and expert woodman died of the cancer on his tongue. He knew that

death was approaching, but he did not relax the reticence of his later

years other than to express a few wishes as to certain things to be done

at his death. Then, when the hands of the kind friends who had ministered

to his dying wants came to lay out the dead body of the adventurous Argonaut,

a discovery was made that was literally astounding. Charley Parkhurst was

a woman.}}

The article noted how unusual it was that Parkhurst could

have lived so long with no one discovering his assigned gender, and to

"achieve distinction in an occupation above all professions calling for

the best physical qualities of nerve, courage, coolness and endurance,

and that she should add to them the almost romantic personal bravery that

enables one to fight one's way through the ambush of an enemy..." was seen

to be almost beyond believing, but there was ample evidence to prove the

case.

1868 vote

The Santa Cruz Sentinel of October 17, 1868, lists Charles

Darkey Parkurst on the official poll list for the election of 1868. There

is no record that Parkhurst actually cast a vote. If he had voted, Parkhust

may have been the first "female" to vote in a presidential election in

California.

Local legend and Parkhurst's gravestone claims that Parkhurst

was the first "female" in the United States to vote. This is incorrect

as a few states allowed women to vote before 1868.

Legacy and honors

The fire station in Soquel, California, has a plaque

reading:

"The first ballot by a woman in an

American presidential election was cast on this site November 3, 1868,

by Charlotte (Charlie) Parkhurst who masqueraded as a man for much of her

life. She was a stagecoach driver in the mother lode country during the

gold rush days and shot and killed at least one bandit. In her later years

she drove a stagecoach in this area. She died in 1879. Not until then was

she found to be a woman. She is buried in Watsonville at the pioneer cemetery."

In 1955, the Pajaro Valley Historical

Association erected a monument at Parkhurst's grave, which reads:

Charley Darkey Parkhurst (1812-1879)

Noted whip of the gold rush days drove stage over Mt. Madonna in early

days of Valley. Last run San Juan to Santa Cruz. Death in cabin near the

7 mile house. Revealed 'one eyed Charlie' a woman. First woman to vote

in the U.S. November 3, 1868.

In 2007, the Santa Cruz County Redevelopment

Agency oversaw the completion of the Parkhurst Terrace Apartments, named

for the stagecoach driver and located a mile along the old stage route

from the place of his death.

|

5. Eleanor Dumont - from Wikipedia

| Madame Moustache was the pseudonym of Eleanor Dumont

(also called Eleonore Alphonsine Dumant), a notorious gambler on the American

Western Frontier, especially during the California Gold Rush. Her nickname

was due to the appearance of a line of dark hair on her upper lip.

She was thought to have been born in France and moved

to America as a young woman.

She was an accomplished card dealer and made a living

from twenty-one and other casino games. Moving from place to place, she

was reported to work in Bodie, California; Deadwood, South Dakota; Fort

Benton, Montana; Pioche, Nevada; Tombstone, Arizona; and San Francisco,

California, among other places.

In Nevada City, California, she opened up the gambling

parlor named "Vingt-et-un" on Broad Street. Only well-kept men were allowed

in, and no women save herself. All the men admired her for her beauty and

charm, but she kept them all a nice distance away. She was a very private

lady, so she flirted, but only to keep the boys coming. Men came from all

around to see the woman dealer - this was rare then - and considered it

a privilege. The parlor found much success, so she decided to go into business

with Dave Tobin, an experienced gambler. They opened up Dumont's Place,

which was very successful until the gold started to dry up in Nevada City.

She left Tobin and Nevada City for brighter things.

There was a brief period in Carson City where she bought

a ranch and some animals. It was there that she fell in love with Jack

McKnight, who conned her out of all of her money. |

|

She moved around from city to city, gambling and building

up her money again. Her age started to increase, and with that a lot of

the beauty that once entranced miners, faded. This is when the famous mustache

began to grow. She still drew crowds, though, and had a long-standing reputation

for dealing fair.

She also added prostitution to her repertoire during these

later years - she became a "madame" of a brothel in the 1860s. To promote

her business, she would parade her girls around the town in carriages,

showing off their beauty in broad daylight, much to the gasping of the

'proper' women.

Her last stop was Bodie, California. One night while gambling,

she misjudged a play and suddenly owed a lot of money. That night she wandered

outside of town and was found dead on September 8, 1879, of an overdose

of morphine, apparently a suicide. Her funeral was attended by a multitude

of all kinds of people.

Though her professions were usually found shady, all who

knew her deemed her honorable and fair. No one dared speak ill against

her.

|

6. Big Nose Kate - from Wikipedia

| Big Nose Kate (born Mary Katherine Horony Cummings November

7, 1850 – November 2, 1940) was a Hungarian-born prostitute and longtime

companion and common-law wife of Old West gunfighter Doc Holliday.

Early life

Mary Katherine Horony (also spelled Harony, Haroney, and

Horoney) was born on November 7, 1850 in Pest, Hungary, the second-oldest

daughter of Hungarian physician Michael Horony.

Immigration to the United States of America

In 1860, Dr. Horony, his second wife Katharina, and his

children left Hungary for the United States, arriving in New York on the

German ship Bremen in September 1860. Earp researcher Glenn G. Boyer was

the first to state that Kate was descended from nobility and that after

her father was appointed personal physician to Emperor Maximilian I of

Mexico the family accompanied the monarch's retinue to Mexico. However,

in none of his published works did Boyer ever cite a source for these assertions.

Furthermore, Gary L. Roberts, in his book, Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend,

the definitive work on the subject, commented: “Patrick A. Bowmaster, “A

Fresh Look at ‘Big Nose Kate,’” NOLA Quarterly 22 (July – September 1998):

12-24, exposes the fallacy of this tale.”

The Horony family settled in a predominantly German area

of Davenport, Iowa in 1862. Horony and his wife died only three years later,

in 1865, within a month of one another. Mary Katherine and her younger

siblings were placed in the home of her brother-in-law, Gustav Susemihl,

and in 1870 they were left in the care of attorney Otto Smith. The 1870

United States Census records for Davenport, Iowa show Kate's younger sister,

15-year-old Wilhelmina (Wilma), living with and working as a domestic for

Austrian-born David Palter and his Hungarian wife Betty.

St. Louis and Dodge City

At age 16, Kate ran away from her foster home and stowed

away on a riverboat bound for St. Louis, Missouri. Kate later claimed that

while she lived in St. Louis she married a dentist named "Silas Melvin"

with whom she had a son, and that both died of yellow fever. No record

has been found to substantiate marriage, birth of a child, or the death

of either Melvin or the child.[original research?] United States Census

records report that a Silas Melvin lived in St. Louis in the mid 1860s

but that he was married to a steamship captain's daughter named Mary Bust.

The census also shows that another Melvin was employed by a St. Louis asylum.

Since Kate met Doc Holliday in the early 1870s, there is speculation that

she may have confused the two and their occupations when recalling the

facts later in her life.

Researcher Jan Collins states that Cummings entered the

Ursuline Convent but didn't remain long. In 1869, she is recorded as working

as a prostitute for madam Blanch Tribole in St. Louis. In 1874, Kate She

was fined for working as a " sporting woman" in a sporting house in Dodge

City, Kansas, run by Nellie "Bessie" (Ketchum) Earp, James Earp's wife.

|

Kate Horony (seated at left) and younger

sister named Wilhelmina in about 1865,

at the time they were orphaned. Kate

is about 15-years-old.

|

Joins Doc Holliday

| In 1876, Kate moved to Fort Griffin, Texas, where in

1877 she met Doc Holliday. Doc said at one point that he considered Kate

his intellectual equal. Kate introduced Holliday to Wyatt Earp. The couple

went with Earp to Dodge City and registered as Mr. and Mrs. J.H. Holliday

at Deacon Cox’s boarding house. Doc opened a dental practice by day but

spent most of his time gambling and drinking. The two fought regularly

and sometimes violently.

According to Kate, the couple later married in Valdosta,

Georgia. They began traveling frequently, but lived in Las Vegas, New Mexico

for about two years. Holliday worked as a dentist by day and ran a saloon

by night. Kate also occasionally worked at a dance hall in Santa Fe.

There are unproven reports that Kate owned and operated

a bordello in Tombstone. (Amongst amateur historians, Big Nose Kate has

often been confused with a Tombstone sporting woman who went by the name

"Rowdy Kate".) She did own a miner's boarding house in Globe, Arizona,

along Broad Street.

By her own account, Kate and Doc went to Trinidad, Colorado,

and then to Las Vegas, New Mexico, where Holliday was briefly a barkeeper

at a saloon on Center Street. Doc and Kate met up again with Wyatt Earp

and his brothers on their way to the Arizona Territory. Virgil Earp had

already been in Prescott before Wyatt persuaded his brothers to move to

Tombstone. Holliday was making money at the gambling tables in Prescott,

and he and Kate parted ways when Kate left for Globe, Arizona, but she

rejoined Holliday soon after he arrived in Tombstone.

|

|

Move to Tombstone

Holliday, like his friend Wyatt, was always looking for

an opportunity to make money and joined the Earps in Tombstone during the

fall of 1880. On March 15, 1881, at 10:00 pm, three cowboys attempted to

rob a Kinnear & Company stagecoach carrying $26,000 in silver bullion

(by the inflation adjustment algorithm: $635,386 in today's dollars) near

Benson, Arizona, during which the popular driver Eli "Budd" Philpot and

passenger Peter Roerig were killed. Cowboy Bill Leonard, a former watchmaker

from New York, was one of three men implicated in the robbery, and he and

Holliday had become good friends.:181 When Kate and Holliday had a fight,

County Sheriff Johnny Behan and Milt Joyce, a county supervisor and owner

of the Oriental Saloon, decided to exploit the situation.

Behan and Joyce plied Big Nose Kate with alcohol and suggested

to her a way to get even with Holliday. She signed an affidavit implicating

Holliday in the murders and attempted robbery. Judge Wells Spicer issued

an arrest warrant for Holliday. The Earps found witnesses who could attest

to Holliday's whereabouts elsewhere at the time of the murders. Kate said

that Behan and Joyce had influenced her to sign a document she didn't understand.

With the Cowboy plot revealed, Judge Spicer freed Holliday. The district

attorney threw out the charges, labeling them "ridiculous".[ After Holliday

was released, he gave Kate money and put her on the stage. Kate returned

to Globe for a time, but she returned to Tombstone in October of that year.

Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

Main article: Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

In a 1939 letter to her niece Lillian Rafferty, Kate claimed

that she was in the Tombstone area with Holliday during the days before

the shootout. Kate reminisced about her stay with Holliday at Fly's Boarding

House, above the photography studio and alongside the alley where the gunfight

at the O.K. Corral took place. Kate is precise regarding minor details

and states that she was with Holliday in Tucson. She recalled attending

a fiesta, which was the San Augustin Feast and Fair in Levin Park on October

1881. On October 20, 1881, Morgan Earp rode to Tucson to alert Holliday

of the impending trouble. According to Kate, Holliday asked her to remain

in Tucson for her safety, but she refused, instead going with Holliday

and Earp.

Kate wrote that on the day of the gunfight, a man entered

Fly's Boarding House with a "bandaged head" and a rifle. He was looking

for Holliday, who was still in bed after a night of gambling. Kate recalled

that the man who was turned away by Mrs. Fly was later identified as Ike

Clanton, whom city marshal Virgil Earp had buffaloed earlier that day when

he found Clanton carrying a rifle and pistol in violation of city ordinances.

Clanton's head was bandaged afterward.

However, it's unlikely that Clanton could have been both

bandaged and carrying a rifle. Virgil Earp had disarmed him earlier that

day and told Ike he would leave Ike's confiscated rifle and revolver at

the Grand Hotel, which was favored by cowboys when they were in town. Ike

testified afterward that he had tried to buy a new revolver at Spangenberger's

gun and hardware store on 4th Street but the owner saw Ike's bandaged head

and refused to sell him one. Clanton was unarmed at the time of the shootout

later that afternoon. Ike testified that he picked up the weapons from

William Soule, the jailer, a couple of days later.

Author Glenn Boyer disputes that Kate saw the gunfight

through the window of the boarding house. Boyer's work, however, has been

rejected by serious scholars.

Kate stated that after Doc Holliday returned to his room,

he sat on the edge of his bed and wept from the shock of what had happened

during the close-range gunfight. "That was awful," Kate claims he said.

"Just awful." Other researchers dispute Boyer's account of events.

After the O.K. Corral and later life

Kate is reported to have made trips to Tombstone to see

Holliday until he left for Colorado in April 1882. In 1887, Kate traveled

to Redstone, Colorado, close to Glenwood Springs, Colorado, to visit with

her brother Alexander. Some historians have tried to connect Kate and Doc

to possible reconciliation attempts between the two.

Marries George Cummings

After Doc Holliday died in 1887, Kate married Irish blacksmith

George Cummings in Aspen, on March 2, 1890. After working several mining

camps throughout Colorado, they moved to Bisbee, Arizona, where she briefly

ran a bakery. After returning to Willcox, Arizona, in Cochise County, Cummings

became an abusive alcoholic and they separated. In 1900, Kate moved to

Dos Cabezas or Cochise and worked for John and Lulu Rath, owners of the

Cochise Hotel. Cummings committed suicide in Courtland, Arizona, in 1915.

Kate is enumerated in the 1910 U.S. Census in Dos Cabezas,

Arizona, as a member of the home of miner John J. Howard. When Howard died

in 1930, Kate was the executrix of his estate. She contacted his only daughter,

who lived in Tempe, Arizona, and settled the inheritance.

In 1931, now 80, Kate contacted her longtime friend, Arizona

Governor George Hunt, and applied for admittance to the Arizona Pioneers'

Home in Prescott, Arizona. The home had been established in 1910 by the

State of Arizona for destitute and ailing miners and male pioneers of the

Arizona Territory. It took Kate six months to be admitted, since the home

had a requirement that residents must be United States citizens. According

to the 1935 Bork interview, Kate was owed money by the Howard estate, but

the amount owed was not enough to buy firewood through the winter, as Kate

had complained in her letters to the governor.

She was admitted as one of the first female residents

of the home. She lived there and became an outspoken resident, assisting

other residents with living comforts. Kate wrote many letters to the Arizona

state legislature, often contacting the governor when she was not satisfied

with their response.

Death and discrepancies in records

Kate died on November 2, 1940, just five days before her

90th birthday, of acute myocardial insufficiency, a condition she started

showing symptoms of the day before her death. Her death certificate states

that she also suffered from coronary artery disease and advanced arteriosclerosis.

Kate's death certificate contained significant discrepancies regarding

her parents' names and her birthplace. Although she was born in Hungary,

her death certificate states she was born in Davenport, Iowa, to father

Marchal H. Michael and mother Catherine Baldwin. The birthplace of both

her parents is shown on the certificate as "unknown". However, it is unknown

who provided the information for the death certificate.

Near the end of her life, several reporters tried to record

Kate's life story, her relationship with Doc Holliday and her time in Tombstone.

She only talked to Anton Mazzonovich and Prescott historian A.W. Bork.

Kate was buried on November 6, 1940, under the name "Mary

K. Cummings" below a modest marker in the Arizona Pioneer Home Cemetery

in Prescott, Arizona.

|

.

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|