| Johnson County War from Wikipedia

The Johnson County War, also known as the War on Powder

River and the Wyoming Range War, was a range war that took place in Johnson,

Natrona and Converse Counties, Wyoming in April 1892. It was fought between

small settling ranchers against larger established ranchers in the Powder

River Country and culminated in a lengthy shootout between local ranchers,

a band of hired killers, and a sheriff's posse, eventually requiring the

intervention of the United States Cavalry on the orders of President Benjamin

Harrison.

The events have since become a highly mythologized and

symbolic story of the Wild West, and over the years variations of the storyline

have come to include some of the west's most famous historical figures

and gunslingers. The storyline and its variations have served as the basis

for numerous popular novels, films, and television shows.

"The Invaders" of The Johnson County Cattle War. Photo

taken at Fort D.A. Russell near Cheyenne, Wyoming, May 1892 |

Background

| Conflict over land was a somewhat common occurrence in

the development of the American West but was particularly prevalent during

the late 19th century and early 20th century when large portions of the

west were being settled by Americans for the first time. It is a period

which historian Richard Maxwell Brown has called the "Western Civil War

of Incorporation" and of which the Johnson County War was part.

In the early days in Wyoming most of the land was in the

public domain, open to stock raising as open range and to homesteading.

Large numbers of cattle were turned loose on the open range by large ranches.

Ranchers would hold a spring roundup where the cows and

the calves belonging to each ranch were separated and the calves branded.

Before the roundup, calves (especially orphan or stray calves) were sometimes

surreptitiously branded. The large ranches defended against cattle rustling

often by forbidding their employees from owning cattle and by lynching

(or threatening to lynch) suspected rustlers. Property and use rights were

usually respected among big and small ranches based on who was first to

settle the land (the doctrine is known as Prior Appropriation) and the

size of the herd. Nonetheless large ranching outfits would sometimes band

together and use their power to monopolize large swaths of range land,

preventing newcomers from settling the area.

The WSGA

Many of the large ranching outfits in Wyoming were organized

as the Wyoming Stock Growers Association (the WSGA) and gathered socially

as the Cheyenne Club in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Comprising some of the state's

wealthiest and most influential residents, the organization held a great

deal of political sway in the state and region. The WSGA organized the

cattle industry by scheduling roundups and cattle shipments. The WSGA also

employed an agency of detectives to investigate cases of cattle theft from

its members' holdings.

The often uneasy relationship between larger, wealthier

ranches and smaller ranch settlers became steadily worse after the poor

winter of 1886-1887 when a series of blizzards and temperatures of 40-50

degrees below 0 °F (-45 °C) had followed an extremely hot and dry

summer.Thousands of cattle were lost and large companies began to appropriate

land and control the flow and supply of water in the area. Some of the

harsher tactics included forcing settlers off their land and setting fire

to settler buildings as well as trying to exclude the smaller ranchers

from participation in the annual roundup. They justified these excesses

on what was public land by using the catch-all allegation of rustling.

Rustling in the local area was likely increasing due to

the harsh grazing conditions, and the illegal exploits of an organized

group of regional rustling outfits was becoming well publicized in the

late 1880s. Well armed bands of horse and cattle rustlers were said to

roam across various portions of Wyoming and Montana, with Montana cattle

interests declaring "War on the Rustlers" in 1889 and Wyoming interests

doing so a year later. In Johnson County, with emotions running high, agents

of the larger ranches killed several alleged rustlers from smaller ranches.

Many were killed on dubious evidence or were simply found dead while the

killers remained anonymous. Frank M. Canton, Sheriff of Johnson County

in the early 1880s and better known as a detective for the WSGA, was rumored

to be behind many of the deaths. The double lynching of Ella Watson and

storekeeper Jim Averell took place in 1889, an event that enraged local

residents. A number of additional dubious lynchings of alleged rustlers

took place in 1891.

A group of smaller Johnson County ranchers led by a local

settler named Nate Champion began to form the Northern Wyoming Farmers

and Stock Growers' Association (NWFSGA) to compete with the WSGA. The WSGA

"blacklisted" the NWFSGA and told them to stop all operations but the NWFSGA

refused the WSGA's order to disband and instead made public their plans

to hold their own roundup in the spring of 1892.

The war

The WSGA, led by Frank Wolcott (WSGA Member and large

North Platte rancher), hired gunmen with the intention of eliminating alleged

rustlers in Johnson County and breaking up the NWFSGA. Twenty-three gunmen

from Paris, Texas and four cattle detectives from the WSGA were hired along

with Idaho frontiersman George Dunning, who later turned against the group.

Some WSGA and Wyoming dignitaries also joined the expedition, including

State Senator Bob Tisdale, state water commissioner W. J. Clarke, and W.

C. Irvine and Hubert Teshemacher, both instrumental in organizing Wyoming's

statehood four years earlier. They were accompanied by surgeon Dr. Charles

Penrose as well as Ed Towse, a reporter for the Cheyenne Sun, and a newspaper

reporter for the Chicago Herald, Sam T. Clover, whose lurid first-hand

accounts later appeared in eastern newspapers. A total expedition of 50

men was organized.

To lead the expedition the WSGA hired Canton, a former

Johnson County Sheriff-turned-gunman and WSGA detective. Canton's gripsack

was later found to contain a list of dozens of rustlers to be either shot

or hanged and a contract to pay the Texans $5 a day plus a bonus of $50

for every rustler killed. The group became known as "The Invaders," or

alternately, "Wolcott's Regulators".

John Clay, a prominent Wyoming businessman, was suspected

of playing a major role in planning the Johnson County invasion. Clay denied

this, saying that in 1891 he advised Wolcott against the scheme and was

out of the country when it was undertaken. He later helped the “invaders”

avoid punishment after their surrender.

The group organized in Cheyenne and proceeded by a specially

hired train to Casper, Wyoming and then toward Johnson County on horseback,

cutting the telegraph lines north of Douglas, Wyoming in order to prevent

an alarm. While on horseback Canton and the gunmen traveled ahead while

the party of WSGA officials led by Wolcott followed a safe distance behind.

|

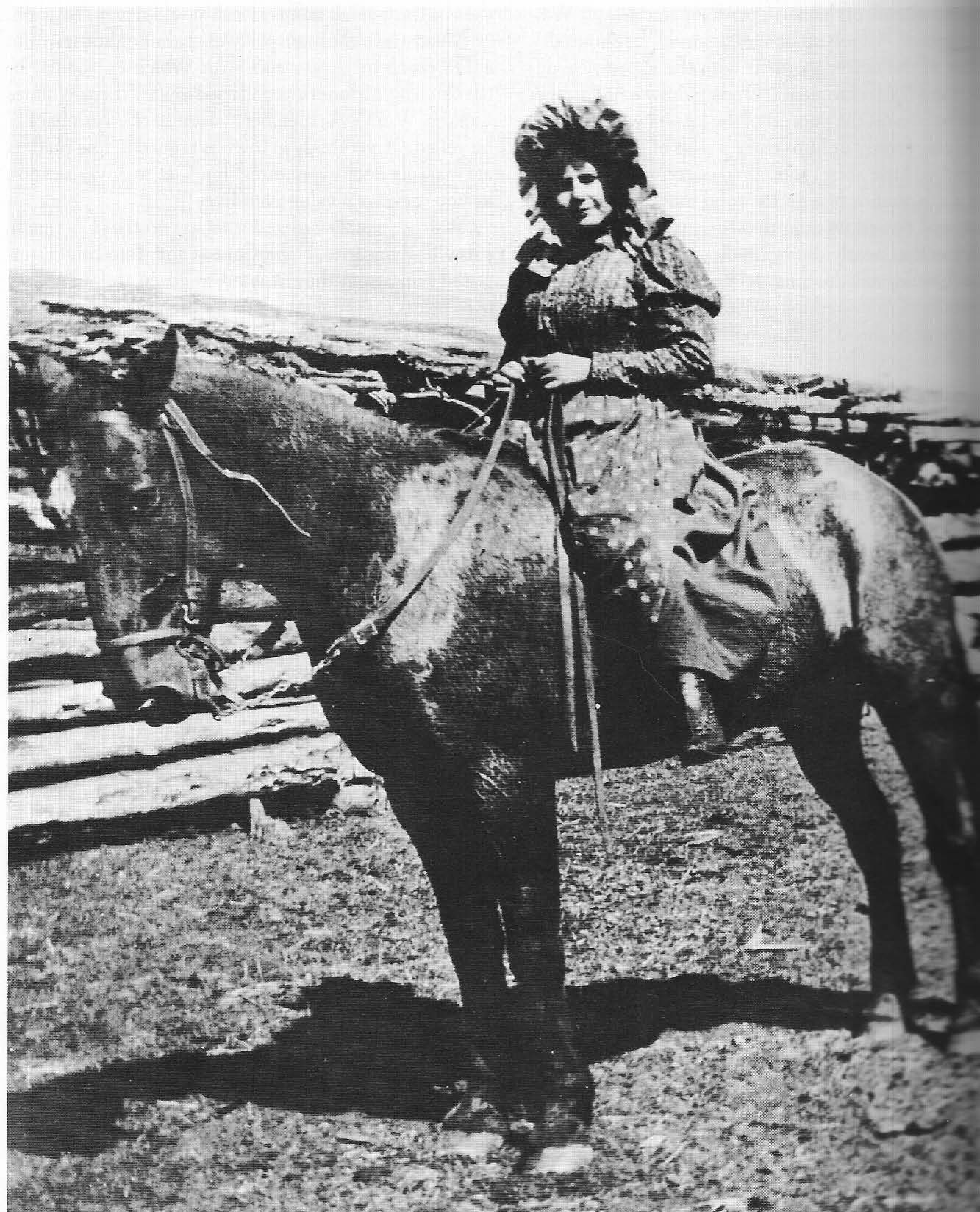

Ella Watson was lynched in 1889 by

wealthy ranchers who accused her

of cattle rustling, a charge that was

later shown to be false.

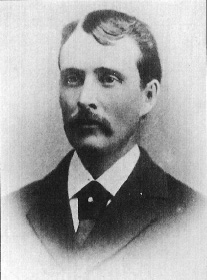

Jim Averell, a Johnson County businessman,

was lynched in 1889 for cattle rustling,

although he owned no cattle

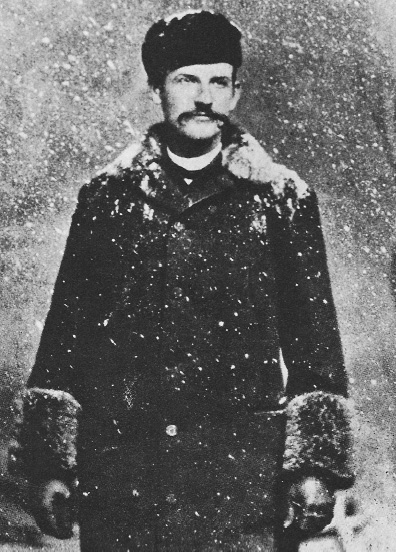

Frank M. Canton, former Sheriff of

Johnson County, was hired to

lead the band of Texas killers

|

Nate Champion and the KC Ranch

The first target of the WSGA was Nate Champion at the

KC Ranch (of which today's town of Kaycee is a namesake), a small rancher

who was active in the efforts of small ranchers to organize a competing

roundup. The group traveled to the ranch late in the night of Friday April

8, 1892, quietly surrounded the buildings and waited for daybreak. Three

men besides Champion were at the KC. Two men who were evidently spending

the night on their way through were captured as they emerged from the cabin

early that morning to collect water at the nearby Powder River, while the

third, Nick Ray, was shot while standing inside the doorway of the cabin

and died a few hours later. Champion was besieged inside the log cabin.

During the siege, Champion kept a poignant journal which

contained a number of notes he wrote to friends while taking cover inside

the cabin. "Boys, I feel pretty lonesome just now. I wish there was someone

here with me so we could watch all sides at once." The last journal entry

read: "Well, they have just got through shelling the house like hail. I

heard them splitting wood. I guess they are going to fire the house tonight.

I think I will make a break when night comes, if alive. Shooting again.

It's not night yet. The house is all fired. Goodbye, boys, if I never see

you again."

With the house on fire, Nate Champion signed his journal

entry and put it in his pocket before running from the back door with a

six shooter in one hand and a knife in the other. As he emerged he was

shot by four men and the invaders later pinned a note on Champion's bullet-riddled

chest that read "Cattle Thieves Beware".

Two passers-by noticed the ruckus that Saturday afternoon

and local rancher Jack Flagg rode to Buffalo (the county seat of Johnson

County) where the sheriff raised a posse of 200 men over the next 24 hours

and the party set out for the KC on Sunday night, April 10.

Standoff at the TA Ranch

| The WSGA group then headed north on Sunday toward Buffalo

to continue its show of force. The posse led by the sheriff caught up with

the WSGA "Invaders" by early Monday morning of the 11th and besieged them

at the TA Ranch on Crazy Woman Creek. The gunmen took refuge inside a log

barn on the ranch. Ten of the gunmen then tried to escape the barn behind

a fusillade but the posse beat them back and killed three. One of the WSGA

group escaped and was able to contact the acting Governor of Wyoming the

next day. Frantic efforts to save the WSGA group ensued and two days into

the siege Governor Barber was able to telegraph President Benjamin Harrison

a plea for help late on the night of April 12, 1892. |

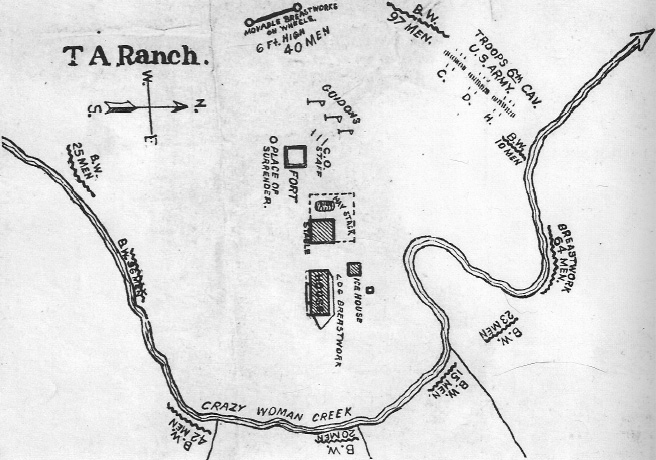

A map of the TA Ranch during the

Johnson County War, depicting the positions

of the Invaders, the posse, and the 6th Cavalry |

The telegram read:

| “ About sixty-one owners of live stock are reported

to have made an armed expedition into Johnson County for the purpose of

protecting their live stock and preventing unlawful roundups by rustlers.

They are at ‘T.A.’ Ranch, thirteen miles from Fort McKinney, and are besieged

by Sheriff and posse and by rustlers from that section of the country,

said to be two or three hundred in number. The wagons of stockmen were

captured and taken away from them and it is reported a battle took place

yesterday, during which a number of men were killed. Great excitement prevails.

Both parties are very determined and it is feared that if successful will

show no mercy to the persons captured. The civil authorities are unable

to prevent violence. The situation is serious and immediate assistance

will probably prevent great loss of life. ” |

| Harrison immediately ordered the U.S. Secretary of War

Stephen B. Elkins to address the situation under Article IV, Section 4,

Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution, which allows for the use of U.S. forces

under the President's orders for "protection from invasion and domestic

violence". The Sixth Cavalry from Fort McKinney near Buffalo was ordered

to proceed to the TA ranch at once and take custody of the WSGA expedition.

The 6th Cavalry left Fort McKinney a few hours later at 2 am on April 13

and reached the TA ranch at 6:45 am. The expedition surrendered to the

Sixth soon after and was saved just as the posse had finished building

a series of breastworks to shoot gunpowder on the invader's log barn shelter

so that it could be set on fire from a distance. The Sixth Cavalry took

possession of Wolcott and 45 other men with 45 rifles, 41 revolvers and

some 5,000 rounds of ammunition.

The text of Barber's telegram to the President was printed

on the front page of The New York Times on April 14, and a first-hand account

of the siege at the T.A. appeared in The Times and the Chicago Herald and

other papers. |

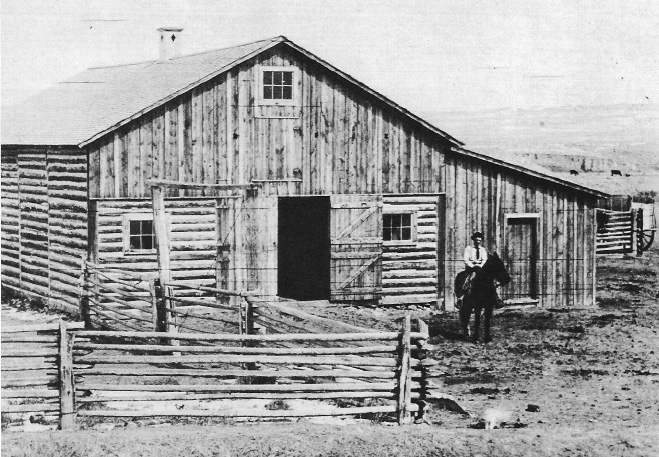

The barn at the TA Ranch, where the

"regulators" were besieged by the

sheriff's posse. |

Arrest and legal action

The WSGA group was taken to Cheyenne to be held at the

barracks of Fort D.A. Russell as the Laramie County jail was unable to

hold that many prisoners. They received preferential treatment and were

allowed to roam the base by day as long as they agreed to return to the

jail to sleep at night. Johnson County officials were upset that the group

was not kept locally at Ft. McKinney. The General in charge of the 6th

Cavalry felt that tensions were too high for the prisoners to remain in

the area. Hundreds of armed locals sympathetic to both sides of the conflict

were said to have gone to Ft. McKinney over the next few days under the

mistaken impression the invaders were being held there.

The Johnson County attorney began to gather evidence for

the case and the details of the WSGA's plan emerged. Canton's gripsack

was found to contain a list of seventy alleged rustlers who were to be

shot or hanged, a list of ranch houses the invaders had burned, and a contract

to pay each Texan five dollars a day plus a bonus of $50 for each person

killed. The invaders' plans reportedly included eventually murdering people

as far away as Casper and Douglas. The Times reported on April 23 that

“the evidence is said to implicate more than twenty prominent stockmen

of Cheyenne whose names have not been mentioned heretofore, also several

wealthy stockmen of Omaha, as well as to compromise men high in authority

in the State of Wyoming. They will all be charged with aiding and abetting

the invasion, and warrants will be issued for the arrest of all of them.”

Charges against the men "high in authority" in Wyoming

were never filed. Eventually the invaders were released on bail and were

told to return to Wyoming for the trial. Many fled to Texas and were never

seen again. In the end the WSGA group went free after the charges were

dropped on the excuse that Johnson County refused to pay for the costs

of prosecution. The costs of housing the men at Fort D.A. Russell were

said to exceed $18,000 and the sparsely populated Johnson County was unable

to pay.

Tensions in Johnson County remained high and the 6th Cavalry

was said to be swaying under the local political and social pressures and

were unable to keep the peace. The 9th Cavalry of "Buffalo Soldiers" was

ordered to Fort McKinney to replace the 6th. In a fortnight the Buffalo

Soldiers moved from Nebraska to the rail town of Suggs, Wyoming where they

created "Camp Bettens" to quell pressure from the local population. One

Buffalo Soldier was killed and two wounded in gun battles with locals.

The 9th Cavalry remained in Wyoming until November.

Aftermath

Emotions ran high for many years following the 'Johnson

County Cattle War' as some viewed the large and wealthy ranchers as heroes

who took justice into their own hands in order to defend their rights,

while others saw the WSGA as heavy-handed vigilantes running roughshod

over the law of the land.

A number of tall tales were spun by both sides afterwards

in an attempt to make their actions appear morally justified. Parties sympathetic

to the invaders painted Nate Champion as the leader of a vast cattle rustling

empire and that he was a leading member of the fabled "Red Sash Gang" of

outlaws that supposedly included the likes of everyone from Jesse James

to the Hole in the Wall Gang. These rumors have since been discredited.

While some accounts do note that Champion wore a red sash at the time of

his death, such sashes were common. While the Hole in the Wall Gang was

known to hide out in Johnson County, there is no evidence that Champion

had any relationship to them.[19] Parties sympathetic to the smaller ranchers

spun tales that included some of the west's most notorious gunslingers

under the employ of the Invaders, including such legends as Tom Horn and

Big Nose George Parrot. Horn did briefly work as a detective for the WSGA

in the 1890s but there is no evidence he was involved in the war.

Political effects

Although many of the leaders of the WSGA's hired force,

such as W. C. Irvine, were Democrats, the ranchers who had hired the group

were tied to the Republican party and their opponents were mostly Democrats.

Many viewed the rescue of the WSGA group at the order of President Harrison

(a Republican) and the failure of the courts to prosecute them a serious

political scandal with overtones of class war. As a result of the scandal,

the Democratic Party became popular in Wyoming for a time, winning the

governorship in 1895 and taking control of both houses of the state legislature

during the two elections after the events. Wyoming voted for the Democrat

William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 U.S. Presidential Election, and Johnson

County was one of the two counties in the state with the largest Bryan

majorities.

Economic analysis

Historian Daniel Belgrad argues that in the 1880s centralized

range management was emerging as the solution to the overgrazing that had

depleted open ranges. Furthermore, cattle prices at the time were low.

Larger ranchers were hurt by mavericking (taking lost, unbranded calves

from other ranchers' herds), and responded by organizing cooperative roundups,

blacklisting, and lobbying for stricter anti-maverick laws. These ranchers

formed the WSGA and hired gunmen to hunt down rustlers, but local farmers

resented the ranchers' collective political power. The farmers moved toward

decentralization and the use of private winter pastures. Randy McFerrin

and Douglas Wills argue that the confrontation represented opposing property

rights systems. The result was the end of the open-range system and the

ascendancy of large-scale stock ranching and farming. The popular image

of the war, however, remains that of vigilantism by aggressive landed interests

against small individual settlers defending their rights.

The Banditti of the Plains

In 1894, witness Asa Shinn Mercer published an indignant

account of the war, titled The Banditti of the Plains. The book was suppressed

for many years as the WSGA tracked down and destroyed all but a few of

the first edition copies from the 1894 printing, and was rumored to have

hijacked and destroyed the second printing as it was being shipped from

a printer north of Denver, Colorado. The book was, however, reprinted several

times in the 20th century.

In popular culture

The Johnson County War, with its overtones of class warfare

and intervention by the President of the United States to save the lives

of a gang of hired killers and set them free, is not a flattering reflection

on the American myth of the west.

The Virginian, a seminal 1902 western novel by Owen Wister,

solved the problem by taking the side of the wealthy ranchers, creating

a myth dealing with the themes of the Johnson County war but bearing little

resemblance to the events. The novel was popular and provided the pulp

for six renditions on the silver screen (in 1914, 1923, 1929, 1946, 1962,

and 2000).

Though not explicitly connected with Johnson County, The

Ox-Bow Incident (1940) by Walter Van Tilburg Clark is a novel that dramatizes

and condemns a lynching of the sort that Wister's novel appears to defend.

Jack Schaefer's popular 1949 novel Shane contained themes

associated with the Johnson County War and took the side of the settlers.

The novel spawned a film Shane (1953) and a 17-episode TV Series (1966).

The 1953 film The Redhead from Wyoming, starring Maureen

O'Hara, dealt with very similar themes and in one scene Maureen O'Hara's

character is told "It won't be long before they're calling you Cattle Kate."

In the 1968 novel True Grit by Charles Portis, the main

character, Rooster Cogburn, was involved in the Johnson County War. In

the early 1890s Rooster had gone north to Wyoming where he was "hired by

stock owners to terrorize thieves and people called nesters and grangers

... I fear that Rooster did himself no credit in what they called the Johnson

County War."

The 1980 film Heaven's Gate and a TV movie called The

Johnson County War (2002) also painted the wealthy ranchers as the "bad

guys." Heaven's Gate was a dramatic romance loosely based on historical

events, while The Johnson County War was based on the 1957 novel Riders

of Judgment by Frederick Manfred.

The story of the Johnson County War from the point of

view of the small ranchers was chronicled by Kaycee resident Chris LeDoux

in his song Johnson County War on the 1989 album Powder River. The song

included references to the burning of the KC Ranch, the capture of the

WSGA men, the intervention of the U.S. Cavalry and the release of the cattlemen

and hired guns.

|

| Mason County War from Wikipedia

The Mason County War, sometime called the Hoodoo War in

reference to a masked vigilante member of a vigilance committee,[1]:89

was a period of lawlessness in 1875-1876 during a "tidal wave of rustling".

The violence resulted in a climate of bitter "National prejudice" between

the "Americans" and "Dutch" or "Germans"s in Mason County, Texas.

Background

Organized bands stole livestock but the spring trail bosses

were also "indifferent to whose cows they drove", picking up mavericks

and even other brands, though the understanding was they were supposed

to return the profits to the rightful owner.

Germans had settled in Mason and Gillespie counties, "loyal

to their adopted country and government when undisturbed" but "were sorely

tried by the rustlers and Indians, who committed many depredations upon

their cattle." In 1860 the county's first Sheriff, Thomas Milligan was

killed by Indians. In 1872, the Germans elected Sheriff John Clark and

Cattle Inspector Dan Hoerster.

Clark and Hoerster organized a posse to reclaim lost cattle

and soon came across a herd stolen by the Backus brothers gang and eight

others, capturing five of them, who were taken back to the Mason jail.

The captives included Lige Backus, Pete Backus, Charley Johnson, Abe Wiggins

and Tom Turley.

Beginning

A posse member, Tom Gamel, later claimed that Sheriff

Clark and Dan Hoerster suggested lynching their captives. In any case,

a mob of forty attempted to break into the jail on the night of 18 February

1875 with a battering ram after failing to get the keys from the jailer,

Deputy John Wohrle. Both Sheriff Clark and the visiting Texas Ranger Lt.

Dan W. Roberts were prevented from interfering with a warning they would

be shot. Clark did gather a posse of about six citizens and, with Roberts,

pursued the mob to the south edge of town where they were hanging the prisoners

from a large post oak. By the time the posse reached the mob, Lige and

Pete Backus, plus Abe Wiggins, were dead, but they managed to save Tom

Turley while Charley Johnson had escaped.

This was the beginning activity of the vigilance committee,

or Hoodoos, who used "ambushes and midnight hangings, to get rid of the

thieves and outlaws who had been holding a "carnival of lawlessness in

Mason County".

Reign of Terror Intensifies

Tom Gamel learned he was the target of the vigilance committee

on 25 March prompting him to gather his friends and proceed into town in

an effort to confront the threat, but Sheriff Clark immediately left. Gamel's

group left after a couple of days, but returned after Sheriff Clark returned

with sixty-two men, all Germans, and both groups agreed to peace with "no

more mobs or hanging".

However, in May, Deputy Wohrle arrested the "prominent

and popular American" Tim Williamson, after Dan Hoerster revoked his year

old bond for stealing a yearling. Williamson worked for Charley Lehmberg

in Loyal Valley, known for paying five dollars a head for unbranded cattle.

Wohrle and Williamson were confronted a short distance from the ranch by

a dozen men led by the German rancher Peter Bader, who shot Williamson

dead. This murder increased the tension between the American and German

factions enormously, especially after the Grand Jury of 12 May did nothing.

Among those now involved was Scott Cooley, the orphan raised by Williamson,

who vowed "he would get the men who did it".

Cooley's Actions

Cooley had been carried off by Indians after they killed

his parents, but later raised by the Williamsons. Cooley served in Texas

Rangers Company D under Captain Perry before taking up farming near Menardville.

After Williamson's murder, Cooley came to Mason, learning as much as he

could about the circumstances and the names of those involved. His first

act of revenge occurred on 10 August 10, when Cooley shot Worhle in the

back of the head while he helped Doc Charley Harcourt dig a well, taking

Worhle's scalp as would an Indian.[

Cooley formed a gang whose members included George Gladden,

John and Mose Beard and Johnny Ringo. Mose Beard and Gladden were ambushed

south of Mason by sixty men led by Peter Bader, Dan Hoerster and Sheriff

Clark, resulting in the death of Beard. Cooley's men, including Johnny

Ringo, then killed Cheney at his home, the individual who had led Beard

and Gladden into the ambush. Hoerster was killed as he rode past the Mason

barber shop by Scott Cooley, Gladden and Bill Coke. Coke was captured and

killed by a Mason posse the next day at John Gamel's.

Texas Rangers Arrive

Under orders from the governor, Major Jones of the Texas

Rangers arrived on 28 September, with ten men from Company D (Cooley's

old unit) and thirty men from Company A, his escort under Captain Ira Long.

Major Jones promptly sent scouts out looking for Cooley but without result

after two weeks.

The remaining justice of the Peace, Wilson Hey, issued

warrants for Sheriff Clark and others, who were arrested, and although

the charges did not stick, Sheriff Clark did resign his office and was

never seen again.

Major Jones' scouts continued to seek Cooley and his gang

to no avail which prompted Jones to confront his Rangers with the opportunity

for those in sympathy with Cooley to "step out of the ranks", which fifteen

did. The remaining Rangers captured Gladden and Ringo.

In November, Scott Cooley's gang killed Charley Bader

at his place and and Peter Bader soon followed the same fate.

At the end of December, 1875, Cooley and Ringo were arrested

by Sheriff A. J. Strickland for threatening the life of Burnet County,

Texas Deputy Sheriff John J. Strickland. They later escaped from the Lampasas

County, Texas jail with the help of forty "Helping Hands".

Aftermath

The summer of 1876 was another period of terror and lawlessness

before Cooley left Mason County for good, either by poison after dining

at the Nimitz Hotel in Fredericksburg or by "brain fever".

Johnny Ringo left the state for Arizona and Gladden headed

for the penitentiary for the murder of Peter Bader. On 21 January 21 1877,

the Mason County Courthouse was burned to the ground and with it the official

records of the Mason County War.

|

| San Elizario Salt War from Wikipedia

The San Elizario Salt War, also known as the Salinero

Revolt or the El Paso Salt War, was an extended and complex political,

social and military conflict over ownership and control of immense salt

lakes at the base of the Guadalupe Mountains of West Texas. What began

in 1866 as a political and legal struggle among Anglo Texan politicians

and capitalists gave rise to an armed struggle waged in 1877 by the ethnic

Mexican inhabitants living in the communities on both sides of the Rio

Grande near El Paso, Texas against a leading politician, supported by the

Texas Rangers. The struggle climaxed with the siege and surrender of 20

Texas Rangers to a popular army of perhaps 500 men in the town of San Elizario,

Texas. The arrival of the African-American 9th Cavalry and a sheriff's

posse of New Mexico mercenaries caused hundreds of Tejanos to flee to Mexico,

some in permanent exile. The right of individuals to own the salt lakes

previously held as a community asset was established by force of arms.

What began as a local quarrel grew in stages to finally

occupy the attention of both the Texas and federal governments. Newspaper

editors throughout the nation covered the story, often in frenzied tone

and with lurid detail. At the conflict's height, as many as 650 men bore

arms. About 20 to 30 men were killed in the 12-year fight for salt, and

perhaps double that number were wounded. The war's damage also included

an estimated $31,050 in property damage. Crop losses were sustained because

local farmers did not till or harvest their fields for several months,

but the wheat loss was estimated at $48,000. To these immediate financial

losses (worth about $1.5 million in 2007) can be added the further political

and economic marginalization of the Mexican-American community of El Paso

County.

Traditionally, the Mexican-American uprising has been

described by historians as a bloody riot by a howling mob. The Texas Rangers

who surrendered, especially their commander, have been described as unfit.

More recent scholarship has placed the Salt War within the context of the

long and often violent social struggle of Mexican-Americans to be treated

as equal citizens and not as a subjugated people. Most recently, the "mob"

has been described as an organized political-military insurgency with the

goal of re-establishing local control of their fundamental political rights

and economic future.

Background

National ambiguity

The Rio Grande is a natural barrier in West Texas. Spain,

and later Mexico, had settled a series of communities along the south banks

of the river, which provided protection from Comanche and Apache raids

from the north. Prior to major water-control projects on the Rio Grande

such as Elephant Butte Dike, which was constructed in the early 20th century,

the river flooded often. San Elizario was a relatively large community

south of the river from its founding in 1789 until an 1831 flood changed

the course of the river, leaving San Elizario on "La Isla", a new island

between the new and old channels of the Rio Grande.

This position relative to the river became more important

in 1836 when the newly independent Republic of Texas proclaimed the Rio

Grande the southern border of the new country. The nationality of the people

of San Elizario was disputed until the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo, the treaty that ended the Mexican-American War, which identified

the "deepest channel", i.e. the southern channel, as the official international

boundary. The status of San Elizario was further made official by the 1853

treaty that sold the territory of the Gadsden Purchase to the United States.

At that time, San Elizario was the largest US community between San Antonio,

Texas, and Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was a major stop on the Camino Real

and was the county seat of the region.

Civil War and Reconstruction

The American Civil War created great changes in the political

landscape of West Texas. The end of the war and Reconstruction brought

many entrepreneurs to the area. The families of San Elizario had deep roots

and were loath to accept the newcomers. Many Republicans settled in the

small trading community of Franklin, Texas, a trading village across the

Rio Grande from the Chihuahua city of El Paso del Norte (present-day Ciudad

Juárez).

By the beginning of the 1870s the Democratic Party had

begun to reclaim political influence in the state. The Democratic operatives,

with their ties to Southern United States, were not accepted by the people

of San Elizario, either, as they retained generational ties to Mexico.

Alliances shifted and rivalries developed between the Hispanic, Republican,

and Democratic factions residing in West Texas.

The Salt

At the base of the Guadalupe Mountains, about 100 mi (160

km) northeast of San Elizario, lie a series of dry salt lakes (located

at: 31.74335°N 105.07668°W). Before the pumping of water and oil

from West Texas, the area had a periodic shallow water table, and capillary

action drew salt of a high purity to the surface. This salt was valuable

for a wide variety of purposes, including preserving meats and replenishing

what sweating took from humans and animals. It was also a commodity used

for barter along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro and was an essential

element in the patio process for extracting the silver from ore in the

Chihuahua mines. Historically, caravans to the salt lakes traveled either

down the Rio Grande and then straight north or via what became the Butterfield

Overland Mail route. In 1863, the people of San Elizario, as a community,

built by subscription a road running east to the salt lakes. The residents

in the Rio Grande valley at El Paso were granted community access rights

to these lakes by the King of Spain. These rights had been grandfathered

in by the Republic of Mexico and in accordance with the Treaty of Guadalupe

Hidalgo. Beginning in 1866, the Texas Constitution allowed individuals

to stake claims for mineral rights, thus overturning the grandfathered

community rights.

Political Phase 1866-1877

Salt Ring and Anti-Salt Ring

In 1870, a group of influential leaders from Franklin,

Texas, claimed the land on which the salt deposits were found. They were

unsuccessful in gaining sole title to the land, and a feud over ownership

and control of the land began. William Wallace Mills favored individual

ownership, Louis Cardis favored the Hispanic community concept of commonwealth,

and Albert Jennings Fountain favored county government ownership with community

access. This led to Cardis and Fountain to join together as the "Anti-Salt

ring", while Mills became the leader of the "Salt ring."

Fountain was elected to the Texas State Senate and began

pushing for his plan of county government ownership with community access.

San Elizario's Spanish priest, Father Antonio Borrajo, opposed the plan

and gained the support of Cardis. On December 7, 1870, Judge Gaylord J.

Clarke, a supporter of Mills, was killed. Fountain and Cardis sparred with

every political and legal tool at their command. The Republican's loss

of state government control in 1873 prompted Fountain to leave El Paso

for his wife's home in New Mexico.

Charles Howard

In 1872, Charles Howard, a Virginian by birth, came to

the region determined to restore the Democratic Party to power in West

Texas. His natural rival was Mills, so he struck up an alliance with Cardis,

who controlled the Hispanic vote in the region. Cardis had a stronger allegiance

to the former citizens of Mexico than to either US political party, and

was influential in swinging their votes in any direction he thought beneficial

to the community or to himself. Howard was elected district judge and about

the same time began feuding with Cardis over who would be the county's

political "top dog".

In the summer of 1877, Howard filed a claim for the salt

lakes in the name of his father-in-law, George B. Zimpelman, an Austin

capitalist. Howard offered to pay any salinero who collected salt the going

rate for its retrieval, but he insisted the salt was his. The Tejanos of

San Elizario, encouraged by Father Borrajo (by now the former pastor),

with the support of Cardis, gathered and kept salt in spite of Howard's

claim. The people did not only look to outside leaders. Falling back on

a long tradition of local self-government, they formed committees (juntas)

in San Elizario and the largely Tejano neighboring towns of Socorro and

Ysleta, Texas, to determine a community-based response to Howard's action.

During the summer of 1877, they held several secretive, decisional, and

organizational meetings.

Salt Uprising 1877-1878

On September 29, 1877, José Mariá Juárez

and Macedonia Gandara threatened to collect a wagonload of salt. When Howard

learned of their activities, he had the men arrested by Sheriff Charles

Kerber and went to court in San Elizario to legally restrain them that

evening, armed men arrested the compliant jurist. Others went in search

of Howard, locating him at Sheriff Kerber's home in Yselta. Under the leadership

of Francisco "Chico" Barela, they seized Howard and marched him back to

San Elizario. For three days, he was held prisoner by several hundred men,

led by Sisto Salcido, Lino Granillo, and Barela. On October 3, he was finally

released upon payment of a $12,000 bond and his written relinquishment

of all rights to the salt deposits. Howard left for Mesilla, New Mexico,

where he briefly stayed at the house of Fountain. He soon returned to the

area, and on October 10, shot and killed Cardis in an El Paso (formerly

Franklin) mercantile store. Howard fled back to New Mexico.

The Tejano people of El Paso County were outraged. They

effectively put a stop to all county government, replacing it with community

juntas and daring the sheriff to take any action against them. In response

to pleas from a frightened Anglo community (numbering fewer than 100 residents

out of 5,000 in the county), Governor Richard B. Hubbard answered by sending

to El Paso Major John B. Jones, commander of the Texas Rangers' Frontier

Battalion. Arriving on November 5, Jones met with the junta leaders, negotiated

their agreement to obey the law (or so he thought) and arranged Howard's

return, arraignment, and release on bail. Jones also recruited 20 new Texas

Rangers, the Detachment of Company C, under the command of Lieutenant John

B. Tays, a native Canadian. Traditionally, Tays has been described as an

uneducated handyman, but later research indicated he was a mining engineer,

El Paso land speculator, and smuggler of Mexican cattle. His appointment

to command the local Ranger detachment was approved by leading Anglos.

The Ranger detachment recruited by Jones and Tays was mixed, composed of

Anglos and a few Tejanos, including an old Indian fighter, several Civil

War veterans, an experienced lawman, at least one outlaw, and a few community

pillars. Individually, they included some capable men, but the unit lacked

tradition or cohesion.

The Rangers

On December 12, 1877, Howard returned to San Elizario

with a company of 20 Texas Rangers led by John B. Tays. Once again, a mob

descended upon them. Howard and the Rangers took cover in the buildings,

eventually taking refuge in the town's church. After a two-day siege, Tays

surrendered the company of Rangers, marking the only time in history a

Texas Ranger unit ever surrendered to a mob. Howard, Ranger Sergeant John

McBride, and merchant and ex-police lieutenant John G. Atkinson were immediately

executed and their bodies hacked and dumped into a well. The Rangers were

disarmed and sent out of town. The civic leaders of San Elizario fled to

Mexico, and the people of the town looted the buildings. In all, 12 people

were killed and 50 wounded.

Consequences

As a result of the unrest, San Elizario lost its status

as county seat, which was relocated to El Paso. The 9th Cavalry of buffalo

soldiers were sent to re-establish Fort Bliss to keep an eye on the border

and the local Mexican population. When the railroad came to West Texas

in 1883, it bypassed San Elizario. The town's population decreased, and

Mexicans lost their political influence in the region.

|

.

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|