Henry Plummer from Wikipedia

| Henry Plummer (1832 – 1864) served as sheriff of what

became Bannack, Montana, from May 24, 1863 until January 10, 1864, when

he was hanged without legal system trial by the controversial Montana Vigilantes.

[Notes of historical clarification: the original Idaho Territory, declared

July 4, 1863 at Lewiston, Idaho included all of what is now Montana. The

Montana territory was created in 1864. Thus at the time of his death, Plummer

was sheriff in Bannock, Idaho Territory. By a 2:1 decision of the Idaho

Territorial Supreme Court, Boise became the capital in 1866.] Some believe

him to have been the head of a gang that was responsible for nearly a hundred

deaths; he was hanged along with twenty-three others for their presumed

crimes.

Life

There is general agreement about his early years only.

There is also general agreement that he was handsome, well spoken and intelligent,

but some see these attributes as a veneer, hiding a dishonest, cruel, crafty,

violent nature. Others see him as a victim of jealous, malicious gossip—character

assassination for personal and political gain.

|

. |

Early years

He was born William Henry Handy Plumer, the last of six

children in Addison, Maine to a family that had settled in Maine in 1764

when it was still a part of the Massachusetts Bay colony. (He changed the

spelling of his surname after moving West. His father died while Henry

was in his teens. In 1852, age 19, he headed west to the gold fields of

California. His mining venture went well: within two years he owned a mine,

a ranch and a bakery in Nevada City. In 1856, he was elected sheriff and

city manager and it was proposed that he should run for state representative

as a Democrat. However, the party was divided, and without its full support,

he lost.

Becoming an outlaw

On September 26, 1857, Plummer shot and killed John Vedder

who had been having an affair with Vedder's wife. In the resulting trial,

Plummer was sentenced to ten years in San Quentin. However, in August,

1859, his many supporters wrote to the governor to seeking a pardon based

on his good character and civic performance; the governor subsequently

granted the pardon, but it was based on his health---Plummer was suffering

from tuberculosis. Then, in 1861, Plummer tried to carry out a citizen's

arrest of William Riley, who had escaped from San Quentin; in the attempt,

Riley was killed. Plummer turned himself in to the police, who accepted

that the killing was justified, but, fearing that his prison record would

prevent a fair trial, recommended that he leave the state.

Life of a criminal

Plummer headed to Washington Territory where gold had

been discovered. However, he once again became involved in a dispute that

ended in a gunfight won by Plummer. This event left him feeling that his

only recourse was to return to Maine. While his skill with guns was keeping

him alive in the violent towns of the gold rush, it was also making it

hard for him to accomplish anything.

Halfway home, waiting for a steamer to reach Fort Benton

on the Missouri River, Plummer was approached by James Vail who was seeking

volunteers to help protect his family from anticipated Indian attacks at

the mission station he was attempting to found in Sun River, Montana. No

passage home being available, Plummer accepted, along with Jack Cleveland,

a horse dealer who had known Plummer in California. While at the mission,

both Plummer and Cleveland fell in love with Vail's attractive sister-in-law,

Electa Bryan; Plummer asked her to marry him and she agreed. As gold had

recently been discovered in nearby Bannack, Montana, Plummer decided to

go there to try to earn enough money to support them both. Cleveland followed

him.

Death

In January 1863, Cleveland, nursing his jealousy, forced

Plummer into a fight and was killed. Fortunately for Plummer, this happened

in a crowded saloon, and there was no doubt that it was self-defense. In

fact, Plummer was viewed very favorably by most town residents and, in

May, he was elected sheriff of Bannack. However, the following winter the

stage was robbed twice, an attempt was made to rob a freight caravan, and

a man was murdered.[citation needed] In late December, while Plummer was

out of town providing an escort to a gold shipment, a group of men calling

themselves the Vigilance Committee formed in nearby Virginia City to take

matters into their own hands. Over the next month, 24 men were hanged,

including, on January 10, 1864, Henry Plummer. The last man hanged by the

vigilantes may have done nothing more than express an opinion that several

of those hanged previously had been innocent.Citation needed

The Montana Vigilantes became an admired group in Montana

history. Beginning in the late 20th century, that view has been widely

challenged. Books have appeared depicting Plummer as an innocent victim.

In recent years, many historical researchers have come to question the

"traditional" histories relating to Henry Plummer, some of which might

have been written by Freemasons. Some of the researchers think that the

Masons played a critical role in the hanging of Henry Plummer and his gang.

However, this is speculative, as Plummer left Bannack as part of a group

and without notice. The vigilantes had to have (1) been organized and ready

when Plummer left and gotten ahead of them, (2) been in sufficiently large

numbers to have stopped Plummer and his associates, (3) possibly held a

"trial," though it might have been a kangaroo court, (4) carried out the

hangings, (5) returned to town without creating suspicion, and (6) kept

the secrets of the actions and details. The one group that most stands

out as meeting all six of the above criteria in organization, secrecy and

status as upstanding citizens was the Freemasons; hence the speculation

of their involvement.

Historical fiction writers, too, have examined the issue.

The most recent is the historical novel by James Gaitis, entitled "A Stout

Cord and a Good Drop" (Globe Pequot Press 2006). In contrast, Frederick

Allen, in his highly praised 2004 book, "A Decent, Orderly Lynching: The

Montana Vigilantes," goes somewhat against this trend. He believes there

is considerable evidence of Plummer's guilt, and he suggests the early

phase of the lynchings was a widely supported response to a real breakdown

of law and order, and a fairly measured response for its time. (This was

the era of the Civil War and vigorous campaigns against Indians.) Allen

does believe, however, that the movement later degenerated into a campaign

of terror that still haunts the state. If so, that would be a strong argumentation

against the Masons.

In May 1993 a posthumous trial on Plummer resulted in

a mistrial because of a split verdict.

Since this trial, more evidence has come to light to prove

Henry Plummer's possible innocence. He was dying of TB when he was hanged

without the drop, therefore he might have died slowly and in agony. [Note:

if the noose is placed to the side, the neck breaks and death is quick.

If a noose is placed behind the head, the result is strangulation. There

is no known record of how Plummer and his accomplices were hanged.] He

simply decided that vigilantism was wrong and presumed some of the executed

might have been innocent. This brought the ire of the ringleader of the

vigilance committee.

The most common account is that the two youngest members

of the gang were spared. One was sent back to Bannack to tell the rest

to get out of the area and the other was sent ahead to Lewiston to do the

same with the others of the gang there. [Lewiston was the territorial connection

to the world, as it had river steamers that transited to the coast at Astoria,

Oregon]. Plummer was known to have traveled to Lewiston during the time

when he was an elected official in Bannack. The hotel registry records

with his signature during the period still exist. Plus, whether the historical

revisionists like it or not, the large gang robberies of gold shipments

ended with Plummer's and the alleged gang members' deaths. One gang member

who was hanged at about the same time with Plummer was Clubfoot George.

|

Elfego Baca from Wikipedia

| Elfego Baca (February 10, 1865 - August 27, 1945) was

a gunman, lawman, lawyer, and politician in the closing days of the American

wild west. Baca was born in Socorro, New Mexico just before the end of

the American Civil War to Francisco and Juana Maria Baca. His family moved

to Topeka, Kansas when he was a young child. Upon his mother’s death in

1880, Baca returned with his father to Belen, New Mexico where his father

became a marshal.

In 1884, at age 19, Baca acquired some guns, and became

a deputy sheriff in (through purchasing a badge or by being appointed is

unclear) Socorro County, New Mexico.

His goal in life was to be a peace officer. He wanted,

he said, “the outlaws to hear my steps a block away.” Southwestern New

Mexico at the time was still relatively sparsely settled cattle ranching

country. Cowboys roamed the land and did as they pleased. They might come

into a town, drink at the saloon, harass the locals, and then shoot up

the town out of boredom. Baca meant to put an end to that.

The Frisco Shootout

In October, 1884, in the town of Lower San Francisco Plaza

(now Reserve, New Mexico), Elfego Baca arrested a drunk cowboy named Charlie

McCarty. Baca flashed his badge at McCarty and took Charlie's gun. McCarty's

fellow cowboys tried to take him by force, but Baca refused and opened

fire on the cowboys, killing the horse of one, which fell on his rider

killing him. Baca shot another Cowboy in the knee.

Justice of the peace Ted White granted Charlie's freedom.

After the verdict, Elfego Baca ran out of the courtroom still in possession

of McCarty's gun. Baca took refuge in the house of Geronimo Armijo.

|

Monument to Elfego Baca

.

.

.

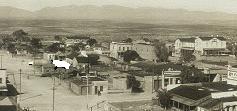

The Frisco Store in Lower Frisco Plaza |

Bert Hearne, a rancher from Spur Lake Ranch, was summoned

to bring Baca back to the Justice for questioning in the murder of Jon

Slaughter's foreman. After Baca refused to come out of the adobe jacal,

Hearne broke down the door and ordered Baca to come out with his hands

up. Soon after that, shots volleyed from the jacal and hit Hearne in the

stomach, resulting in his death.

A standoff with the cowboys ensued. The number of cowboys

that gathered has been disputed, with villagers at the scene reporting

about forty were present, while Elfego himself later claiming there had

been at least eighty. Allegedly, the cowboys fired more than 4,000 shots

into the house, until the adobe building was full of holes. Incredibly,

not one of the bullets struck Baca. (The floor of the home is said to have

been slightly lower than ground level; thus Baca was able to escape injury.)

During the siege, Baca shot and killed four of his attackers

and wounded eight others. After about 33 hours, and roughly 1,000 rounds

of open fire, the battle ended when Francisquito Naranjo convinced Baca

to surrender. In May 1885, Baca was charged with murder for the death of

Jon Slaughter's foreman and Bert Hearne. He was jailed to await his trial.

In August 1885, Baca was acquitted after the door of Armijo’s house was

entered as evidence. It had more than 400 bullet holes in it. The incident

became known as the Frisco Shootout. Rumor has it that Elfego Baca's defense

attorney had false documentation proving Baca's legal deputization because

Baca's biography suggests he deputized himself just before the arrest of

Charlie McCarty.

Law and Order

Baca officially became the sheriff of Socorro County and

secured indictments for the arrest of the area's lawbreakers. Instead of

ordering his deputies to pursue the wanted men, he sent each of the accused

a letter. It said, "I have a warrant here for your arrest. Please come

in by March 15 and give yourself up. If you don’t, I’ll know you intend

to resist arrest, and I will feel justified in shooting you on sight when

I come after you." Most of the offenders turned themselves in voluntarily.

In 1888, Baca became a U.S. Marshal. He served for two

years and then began studying law. In December 1894, he was admitted to

the bar and joined a Socorro law firm. He practiced law on San Antonio

Street in El Paso between 1902 and 1904.

Political life

Baca held a succession of public offices, including county

clerk, mayor and school superintendent of Socorro County, and district

attorney for Socorro and Sierra Counties. In his book The Shooters, Leon

Metz writes that “most reports say he was the best peace officer Socorro

ever had.”

From 1913 to 1916, Baca served as the official representative

in the U.S. of Victoriano Huerta's government during the Mexican Revolution.

In April 1915, Baca was charged with criminal conspiracy for allegedly

masterminding the November 1914 escape of Mexican general José Inés

Salazar escaped from the Albuquerque jail. Successfully defended by the

New Mexican lawyer and politician Octaviano Larrazolo, Baca's reputation

grew among Southwestern residents.

When New Mexico became a state in 1912, Baca unsuccessfully

ran for Congress as a Republican. Nevertheless, he remained a valued political

figure because of his ability to turn out the vote among the Hispanic population.

Working at times as a private detective, Baca also took a job as a bouncer

in a casino across the border in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

Baca worked closely with New Mexico’s longtime Senator

Bronson Cutting as a political investigator and wrote a weekly column in

Spanish praising Cutting’s work on behalf of local Hispanics. Baca considered

running for governor despite his declining health, but he failed to secure

the Democratic Party’s nomination for district attorney in 1944.

Metz, his biographer, wrote: “Elfego was, and is, controversial.

He drank too much; talked too much ... he had a weakness for wild women.

He was often arrogant and, of course, he showed no compunction about killing

people.” On his 75th birthday, Baca told the Albuquerque Tribune that as

a lawyer he had defended 30 people charged with murder, and only one went

to the penitentiary.

In July 1936, several years before his death, Janet Smith

conducted an interview with Elfego Baca. Her notes can be found in the

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, WPA Federal Writers’ Project

Collection. Baca told Smith, “I never wanted to kill anybody, but if a

man had it in his mind to kill me, I made it my business to get him first.”

Legends

Another legend says that Baca stole a pistol from Pancho

Villa, and the angry Villa put a price of $30,000 on Baca’s head. Obviously,

it was never collected.

One often told story says that once when he was practicing

law in Albuquerque, Baca received a telegram from a client in El Paso,

Texas. "Need you at once," it said, "Have just been charged with murder."

To which Baca is supposed to have responded with a telegram saying, "Leaving

at once with three eyewitnesses."

Walt Disney television series

In 1958, Walt Disney Studios released a television miniseries

entitled The Nine Lives of Elfego Baca and starring Robert Loggia in the

title role. Significant is the care Disney took to depict the famous siege

in as authentic a manner as possible, given the known details. Among those

who appeared in the series were Skip Homeier, Raymond Bailey, and I. Stanford

Jolley. Episodes of the series were later edited into a movie titled Elfego

Baca: Six Gun Law, which was released in 1962.

The theme song's tag line was, "And the legend was that

/ Like el gato, "the cat" / Nine lives had Elfego Baca."

|

Camillus "Buck" Sydney Fly from Wikipedia

| Camillus "Buck" Sydney Fly (2 May 1849 – 12 October 1901)

was an American photographer most noted for the many photographs he took

during Tombstone, Arizona's wild and wooly days. He was also a witness

in 1881 to the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, which took place outside his

photography studio.

He later served as a lawman and as Cochise County Sheriff

from 1895 to 1897. His photographs are legendary and highly prized.

Early life

His parents were originally from Andrew County, Missouri.

Shortly after Camillus' birth, they migrated to California, eventually

settling in Napa County.

Tombstone, Arizona

He married Mary “Mollie” E. Goodrich on September 29,

1879 in San Francisco. Mary, who was also a photographer, and Camillus

soon moved to Arizona Territory, where they settled in Tombstone in December,

1879. Fly and his wife immediately set up a photographic studio in a tent

before going to work on more permanent quarters.

|

.

1908 View of "O.K. Corral fight site" in

white, just left of Fly's studio, which is still

standing in this photo. Fly's studio is

immediately to the viewer's right of the

large white patch; the O.K. Corral office

building is at the near corner, between

Fly's and the viewer. The scene is from

a panorama of Tombstone taken from

the room of the County Courthouse in 1908. |

In July, 1880, they opened a 12-room boarding house, and

a separate studio called the “Fly Gallery” in the back of the boarding

house located at 312 Fremont Street in Tombstone.

On October 26, 1881, Fly was in a unique position, as

the infamous Gunfight at the O.K. Corral actually took place in an alley

between his boarding house and the next house west of it. During the shootout,

Cochise County Sheriff John Behan took cover inside the boarding hourse,

watching the gunplay, only to be joined by Ike Clanton who fled in terror

proclaiming he was unarmed. When the smoke cleared, it was Fly, armed with

a Henry rifle, who disarmed Billy Clanton as he lay dying against the house

next door. If Fly ever took any photos of the scene of the shootout scene

which was next to his own studio, they have been lost.

During this time, Fly and Mary adopted a little girl they

called Kitty, but Mary continued to run the boarding house and studio as

Camillus traveled around the area taking photographs. While her husband

was out, she acted as one of the few female photographers of the times,

taking pictures of anyone who could pay the studio price of 35 cents.

In March, 1886, Fly accompanied General George Crook to

the Canyon de Los Embudos for the negotiations with Geronimo. He became

most famous for the photographs he took of the negotiations. His photos

of Geronimo and the other free Apaches, taken on March 25 and 26th, are

famous as the only existing photographs of a native American while still

at war with the United States.

Fly had become a heavy drinker and the year after these

famous photographs were taken, his wife Mary took their child and separated

from her husband. He then left Tombstone on December 17, 1887 and toured

Arizona with his photographs, briefly establishing a studio in Phoenix

in 1893. However, the following year, he returned to the area. In the meantime,

Mary continued to run the studio in Tombstone during his absence.

| Sheriff Fly

Though his drinking was becoming more and more heavy,

he was elected as the Cochise County Sheriff in 1895 and served for two

years.

Death

Fly ranched in the Chiricahua Mountains, until his death

at Bisbee, on October 12, 1901. Though Camillus and his wife had been separated

for years, she was at his bedside when he died, and made arrangements to

have his body returned to Tombstone, where it was buried in the Tombstone

Cemetery (this is the new Tombstone city cemetery, not the "old city cemetery"

which became a legendary Boot Hill).

Mary Fly continued to run the Tombstone gallery on her

own and in 1905, she published a collection of her husband's Indian campaign

photographs entitled "Scenes in Geronimo's Camp: The Apache Outlaw and

Murderer." In 1912, the boarding house was the victim of a fire, which

burned it completely (it has since been rebuilt). This incident prompted

Mary to finally retire. Moving to Los Angeles, she donated her husband’s

collection of negatives to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

She died in 1925.

Fly took this photo of Geronimo in March 1886, before

his surrender to General Crook on September 4.

|

Ike Clanton,

Tombstone, about

1881, by C. S. Fly. |

Scene in Geronimo's camp before surrender to

General Crook, March 27, 1886: Geronimo and

Natches mounted; Geronimo's son (Perico)

standing at his side holding baby |

The reconstructed Fly's photography studio |

Famous photos

Tom McLaury, Frank McLaury, and Billy Clanton in their

caskets after the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and also the only known

photograph of Billy Clanton.

Geronimo and Gen. Crook at Cañon de Los Embudos,

Sonora, March 27, 1886.

|

.

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|