| Vaquero from Wikipedia

The vaquero (Spanish: vaquero or Portuguese: vaqueiro)

is a horse-mounted livestock herder of a tradition that originated on the

Iberian peninsula. Today the vaquero is still a part of the doma vaquera,

the Spanish tradition of working riding. The vaquero traditions developed

in Mexico from methodology brought to Mesoamerica from Spain also became

the foundation for the North American cowboy.

The vaqueros of the Americas were the horsemen and cattle

herders of Spanish Mexico, who first came to California with the Jesuit

priest Eusebio Kino in 1687, and later with expeditions in 1769 and the

Juan Bautista de Anza expedition in 1774. They were the first cowboys in

the region.

In the modern United States and Canada, remnants of two

major and distinct vaquero traditions remain, known today as the "Texas"

tradition and the "Spanish", "Vaquero", or "California" tradition. The

popular "horse whisperer" style of natural horsemanship was originally

developed by practitioners who were predominantly from California and the

Northwestern states, clearly combining the attitudes and philosophy of

the California vaquero with the equipment and outward look of the Texas

cowboy. The natural horsemanship movement openly acknowledges much influence

of the vaquero tradition.

The cowboys of the Great Basin still use the term "buckaroo",

which may be a corruption of vaquero, to describe themselves and their

tradition.

Etymology

| Vaquero is a Spanish word for a herder of cattle. It

derives from vaca, meaning "cow", which in turn comes from the Latin word

vacca.

A related term, buckaroo, still is used to refer to a

certain style of cowboys and horsemanship most often seen in the Great

Basin region of the United States that closely retains characteristics

of the traditional vaquero. Some linguists have speculated that the words

"buckaroo" and "vaquero" may derive from Arabic words related to cattle,

transliterated by some as bakara or bakhara, and suggests the words may

have entered Spanish during the centuries of Islamic rule. The word for

cattle in Arabic: baqar, and the Arabic word baqqar means "cowherd".

History

The origins of the vaquero tradition come from Spain,

beginning with the hacienda system of medieval Spain. This style of cattle

ranching spread throughout much of the Iberian peninsula and later, was

imported to the Americas. Both regions possessed a dry climate with sparse

grass, and thus large herds of cattle required vast amounts of land in

order to obtain sufficient forage. The need to cover distances greater

than a person on foot could manage gave rise to the development of the

horseback-mounted vaquero. Various aspects of the Spanish equestrian tradition

can be traced back to Arabic rule in Spain, including Moorish elements

such as the use of Oriental-type horses, the jineta riding style characterized

by a shorter stirrup, solid-treed saddle and use of spurs, the heavy noseband

or hackamore, (Arabic: šakima, Spanish jaquima) and other horse-related

equipment and techniques. Certain aspects of the Arabic tradition,

such as the hackamore, can in turn be traced to roots in ancient Persia.

Arrival in the Americas

During the 16th century, the Conquistadors and other Spanish

settlers brought their cattle-raising traditions as well as both horses

and domesticated cattle to the Americas, starting with their arrival |

Classic vaquero style hackamore

equipment. Horsehair mecates top

row, rawhide bosals in second

row with other equipment

Image of a man and horse in

Mexican-style equipment,

horse in a two-rein bridle

|

in what today is Mexico and Florida. The traditions of Spain

were transformed by the geographic, environmental and cultural circumstances

of New Spain, which later became Mexico and the Southwestern United States.

In turn, the land and people of the Americas also saw dramatic changes

due to Spanish influence.

The arrival of horses in the Americas was particularly

significant, as equines had been extinct there since the end of the prehistoric

ice age. However, horses quickly multiplied in America and became crucial

to the success of the Spanish and later settlers from other nations. The

earliest horses were originally of Andalusian, Barb and Arabian ancestry,

but a number of uniquely American horse breeds developed in North and South

America through selective breeding and by natural selection of animals

that escaped to the wild and became feral. The Mustang and other colonial

horse breeds are now called "wild", but in reality are feral horses—descendants

of domesticated animals. Mesteñeros were vaqueros that caught, broke

and drove Mustangs to market in Mexico and later the American territories

of what is now Northern Mexico, Texas, New Mexico and California. They

caught the horses that roamed the Great Plains and the San Joaquin Valley

of California, and later in the Great Basin, from the 18th century to the

early 20th century.

18th and 19th centuries

| The Spanish tradition evolved further in what today is

Mexico and the Southwestern United States into the vaquero of northern

Mexico and the charro of the Jalisco and Michoacán regions. Most

vaqueros were men of mestizo and Native American origin while most of the

hacendados (ranch owners) were ethnically Spanish. Mexican traditions spread

both South and North, influencing equestrian traditions from Argentina

to Canada.

As English-speaking traders and settlers expanded westward,

English and Spanish traditions, language and culture merged to some degree.

Before the Mexican-American War in 1848, New England merchants who traveled

by ship to California encountered both hacendados and vaqueros, trading

manufactured goods for the hides and tallow produced from vast cattle ranches.

American traders along what later became known as the Santa Fe Trail had

similar contacts with vaquero life. Starting with these early encounters,

the lifestyle and language of the vaquero began a transformation which

merged with English cultural traditions and produced what became known

in American culture as the "cowboy".

Mesteñeros were vaqueros that caught, broke and

drove Mustangs to market in the Spanish and later Mexican, and still later

American territories of what is now Northern Mexico, Texas, New Mexico

and California. They caught the horses that roamed the Great Plains and

the San Joaquin Valley of California, and later in the Great Basin, from

the 18th century to the early 20th century.

|

Modern child in Mexican parade wearing

charro attire on horse outfitted in

vaquero-derived equipment including

wide, flat-horned saddle, bosalito

and bit, carrying romal reins and reata |

Modern America

Distinct regional traditions arose in the United States,

particularly in Texas and California, distinguished by local culture, geography

and historical patterns of settlement. In turn, the California tradition

had an influence on cattle handling traditions in Hawaii. The "buckaroo"

or "California" tradition, most closely resemblied that of the original

vaquero, while the "Texas" tradition melded some Spanish technique with

methods from the eastern states, creating separate and unique styles indigenous

to the region. The modern distinction between vaquero and buckaroo within

American English may also reflect the parallel differences between the

California and Texas traditions of western horsemanship.

| California tradition

The Spanish or Mexican vaquero who worked with young,

untrained horses, arrived in the 1700s and flourished in California and

bordering territories during the Spanish Colonial period. Settlers from

the United States did not enter California until after the Mexican-American

War, and most early settlers were miners rather than livestock ranchers,

leaving livestock-raising largely to the Spanish and Mexican people who

chose to remain in California. The California vaquero or buckaroo, unlike

the Texas cowboy, was considered a highly-skilled worker, who usually stayed

on the same ranch where he was born or had grown up. He generally married

and raised a family. In addition, the geography and climate of much of

California was dramatically different from that of Texas, allowing more

intensive grazing with less open range, plus cattle in California were

marketed primarily at a regional level, without the need (nor, until much

later, even the logistical possibility) to be driven hundreds of miles

to railroad lines. Thus, a horse- and livestock-handling culture remained

in California and the Pacific Northwest that retained a stronger direct

Spanish influence than that of Texas.

Cowboys of this tradition were dubbed buckaroos by English-speaking

settlers. The words "buckaroo" and Vaquero are still used on occasion in

the Great Basin, parts of California and, less often, in the Pacific Northwest.

Elsewhere, the term "cowboy" is more common. The word "buckaroo" is, according

to the Oxford English Dictionary, a corruption of vaquero, and shows phonological

characteristics compatible with that origin. "Buckaroo" officially appeared

in American English in 1889 and is believed to have originated as an anglicized

version of vaquero, though there is a folk etymology that the term derived

from "bucking", a behavior seen in some young or fresh horses. One author

suggested that "buckaroo" comes not from vaquero but from an African word,

Efik: bakara, meaning "white man, master, boss." However, given the strong

Hispanic influence and dearth of African-American cowboys in the region,

this hypothesis is highly unlikely.

Texas tradition

A Texas-style bosal with added fiador, designed for starting

an unbroke horse

The Texas tradition arose from a combination of cultural

influences, as well as the need to adapt to the geography and climate of

west Texas and, later, the need to conduct long cattle drives to get animals

to market. In the early 1800s, the Spanish Crown, and later, independent

Mexico, offered empresario grants in what would later be Texas to non-citizens,

such as settlers from the United States. In 1821, Stephen F. Austin and

his East Coast comrades became the first Anglo-Saxon community speaking

Spanish. Following Texas independence in 1836, even more Americans immigrated

into the empresario ranching areas of Texas. Here the settlers were strongly

influenced by the Mexican vaquero culture, borrowing vocabulary and attire

from their counterparts, but also retaining some of the livestock-handling

traditions and culture of the Eastern United States and Great Britain.

Following the American Civil War, vaquero culture diffused

eastward and northward, combining with the cow herding traditions of the

eastern United States that evolved as settlers moved west. Other influences

developed out of Texas as cattle trails were created to meet up with the

railroad lines of Kansas and Nebraska, in addition to expanding ranching

opportunities in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain Front, east of the

Continental Divide. The Texas-style vaquero tended to be an itinerant single

male who moved from ranch to ranch. |

Finished "straight-up spade bit" with

California-style bosalito and bridle.

A "Wade" saddle, popular with working

ranch Buckaroo tradition riders, derived

from vaquero saddle designs |

Hawaiian Paniolo

The Hawaiian cowboy, the paniolo, is also a direct descendant

of the vaquero of California and Mexico. Experts in Hawaiian etymology

believe "Paniolo" is a Hawaiianized pronunciation of español. (The

Hawaiian language has no /s/ sound, and all syllables and words must end

in a vowel.) Paniolo, like cowboys on the mainland of North America, learned

their skills from Mexican vaqueros.

By the early 19th century, Capt. George Vancouver's gift

of cattle to Pai`ea Kamehameha, monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, had multiplied

astonishingly, and were wreaking havoc throughout the countryside. About

1812, John Parker, a sailor who had jumped ship and settled in the islands,

received permission from Kamehameha to capture the wild cattle and develop

a beef industry.

The Hawaiian style of ranching originally included capturing

wild cattle by driving them into pits dug in the forest floor. Once tamed

somewhat by hunger and thirst, they were hauled out up a steep ramp, and

tied by their horns to the horns of a tame, older steer (or ox) that knew

where the paddock with food and water was located. The industry grew slowly

under the reign of Kamehameha's son Liholiho (Kamehameha II). Later, Liholiho's

brother, Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III), visited California, then still a

part of Mexico. He was impressed with the skill of the Mexican vaqueros,

and invited several to Hawai`i in 1832 to teach the Hawaiian people how

to work cattle.

Even today, traditional paniolo dress, as well as certain

styles of Hawaiian formal attire, reflect the Spanish heritage of the vaquero.

The traditional Hawaiian saddle, the noho lio, and many other tools of

the cowboy's trade have a distinctly Mexican/Spanish look and many Hawaiian

ranching families still carry the names of the vaqueros who married Hawaiian

women and made Hawai`i their home.

|

Bird Cage Theatre from Wikipedia

| The Bird Cage Theatre was a combination theater, saloon,

gambling parlor and brothel that operated from 1881 to 1889 in Tombstone,

Arizona during the height of the silver boom.

The Bird Cage Theatre was opened on December 25, 1881

by William “Billy” Hutchinson and his wife Lottie. Its name apparently

referred to the 14 “cages” or boxes that were situated on two balconies

on either side of the main central hall. These boxes (also referred to

as “cribs”) had drapes that could be drawn while prostitutes entertained

their clients. The main hall contained a stage and orchestra pit at one

end where live shows were performed.

One apocryphal story alleges that the Bird Cage Theatre

took its name from the popular early 20th-century song “A Bird in a Gilded

Cage”. According to this story, the establishment was originally named

the “Elite Theatre Opera House”. One day shortly after it opened, Eddie

Foy, Sr. and songwriter Arthur J. Lamb were standing at the bar discussing

the ladies who performed there, and Lamb allegedly said they were like

“birds in gilded cages”. He then |

The Bird Cage Theater

as it appears today. |

worked out the song on a piano in the saloon, after which

it was sung by an unknown singer (Lillian Russell in some versions of the

story) who was called back by the roaring crowd eight times. However, Lamb

was born in 1870 (and therefore would have been no older than 11 or 12

years old at the time of this story). Moreover, it appears that the establishment

was named the Bird Cage Theatre from the time it opened. Its name was briefly

changed to the “Elite Theater” after it was acquired by Joe and Minnie

Bignon in 1882 before being changed back to the Bird Cage Theatre.

The Bird Cage Theatre operated continuously – 24 hours

a day, 365 days a year – for the next 8 years. It gained a reputation as

one of the wildest places in the country, prompting The New York Times

to report in 1882 that "the Bird Cage Theatre is the wildest, wickedest

night spot between Basin Street and the Barbary Coast". More than 120 bullet

holes are evident throughout the building.

Aside from Lillian Russell, many other famous entertainers

of the day were alleged to have performed there over the years, including

Eddie Foy, Sr., Lotta Crabtree and Lillie Langtry. In 1882, Fatima allegedly

performed her belly-dancing routine at the Bird Cage Theatre.

The basement poker room is said to be the site of the

longest-running poker game in history. Played continuously 24 hours a day

for eight years, five months, and three days, legend has it that as much

as 10 million dollars changed hands during the marathon game, with the

house retaining 10 percent. Some of the participants were Doc Holliday,

Bat Masterson, Diamond Jim Brady, and George Hearst. When ground water

began seeping into the mines in the late 1880s the town went bust, the

Bird Cage Theatre along with it. The poker game ended and the building

was sealed up in 1889.

The building was not opened again until it was purchased

in 1934, and the new owners were delighted to find that almost nothing

had been disturbed in all those years. It has been a tourist attraction

ever since, and is open to the general public year-round, from 8:00 am

to 6:00 pm daily.

The theater is said to be haunted and has been featured

in the paranormal investigation shows Ghost Hunters in 2006, Ghost Adventures

and Ghost Lab in 2009, and Fact or Faked: Paranormal Files in 2011.

|

Lasso from Wikipedia

| A lasso (play /læsou/ or /læ'sui/), also

referred to as a lariat, riata, or reata (all from Spanish la reata), is

a loop of rope that is designed to be thrown around a target and tighten

when pulled. It is a well-known tool of the American cowboy. The word is

also a verb; to lasso is to successfully throw the loop of rope around

something. Although the tool has several proper names, such terms are rarely

employed by those who actually use it; nearly all cowboys simply call it

a "rope," and the use of such "roping." Amongst most cowboys, the use of

other terms - especially "lasso" - quickly identifies one as a layman.

A lariat is made from stiff rope so that the noose stays

open when the lasso is thrown. It also allows the cowboy to easily open

up the noose from horseback to release the cattle because the rope is stiff

enough to be pushed a little. A high quality lasso is weighted for better

handling. The lariat has a small reinforced loop at one end, called a honda

or hondo, through which the rope passes to form a loop. The honda can be

formed by a honda knot (or another loop knot), an eye splice, a seizing,

rawhide, or a metal ring. The other end is sometimes tied simply in a small,

tight, overhand knot to |

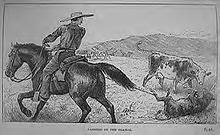

Lassoing on the prairie (from

the book Prairie Experiences in

Handling Cattle and Sheep,

by Major W. Shepherd, 1884) |

prevent fraying. Most modern lariats are made of stiff nylon

or polyester rope, usually about 5/16" or 3/8" in diameter and in lengths

of 28', 30', 35' for arena-style roping and anywhere from 45' to 70' for

Californio-style roping. The reata is made of braided (or less commonly,

twisted) rawhide and is made in lengths from 50' to over 100'. Mexican

maguey (agave) and cotton ropes are also used in the longer lengths.

The lariat is used today in rodeos as part of the competitive

events such as calf roping and team roping. It is also still used on working

ranches to capture cattle or other livestock when necessary. After catching

the cattle, the lariat can be tied or wrapped (dallied) around the horn,

a typical feature on the front of a western saddle. With the lariat around

the horn, the cowboy can use his horse as the equivalent of a tow truck

with a winch.

Part of the historical culture of both the vaqueros of

Mexico and the cowboys of the Western United States is a related skill

now called "trick roping", a performance of assorted lasso spinning tricks.

Will Rogers was a well-known practitioner of trick roping and the natural

horsemanship practitioner Buck Brannaman also got his start as a trick

roper when he was a child.

History

Pharaoh ready to rope the sacred

bull. A carving at the temple

of Seti I, Abydos, Egypt. |

Lassos are not only part of North American culture; relief

carvings at the ancient Egyptian temple of Pharaoh Seti I at Abydos, built

c.1280 BC, show the pharaoh holding a lasso, then holding onto a bull roped

around the horns. They were also used by Tatars and are still used by the

Sami people and Finns in reindeer herding. In Mongolia, a variant of the

lasso called an uurga (Mongolian: yypra) is used, consisting of a rope

loop at the end of a long pole. |

|

.

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|