| Mexican–American War from Wikipedia

The Mexican–American War, also known as the First American

Intervention, the Mexican War, or the U.S.–Mexican War, was an armed conflict

between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848 in the wake of the

1845 U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered part of its territory

despite the 1836 Texas Revolution.

American forces invaded New Mexico, the California Republic,

and parts of what is currently northern Mexico; meanwhile, the American

Navy conducted a blockade, and took control of several garrisons on the

Pacific coast of Alta California, but also further south in Baja California.

Another American army captured Mexico City, and forced Mexico to agree

to the cession of its northern territories to the U.S.

American territorial expansion to the Pacific coast was

the goal of President James K. Polk, the leader of the Democratic Party.

However, the war was highly controversial in the U.S., with the Whig Party

and anti-slavery elements strongly opposed. Heavy American casualties and

high monetary cost were also criticized. The major consequence of the war

was the forced Mexican Cession of the territories of Alta California and

New Mexico to the U.S. in exchange for $18 million. In addition, the United

States forgave debt owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens. Mexico

accepted the Rio Grande as its national border, and the loss of Texas.

The political aftermath of the war raised the slavery issue in the U.S.,

leading to intense debates that pointed to civil war; the Compromise of

1850 provided a brief respite.

In Mexico, terminology for the war include (primera) intervención

estadounidense en México (United States' (First) Intervention in

Mexico), invasión estadounidense de México (The United States'

Invasion of Mexico), and guerra del 47 (The War of 1847).

Background

Mexico was torn apart by bitter internal political battles

that verged on civil war, even as it was united in refusing to recognize

the independence of Texas. Mexico threatened war with the U.S. if it annexed

Texas. Meanwhile President Polk's spirit of Manifest Destiny was focusing

U.S. interest on westward expansion

Designs on California

In 1842, the American minister in Mexico Waddy Thompson,

Jr. suggested Mexico might be willing to cede California to settle debts,

saying: "As to Texas I regard it as of very little value compared with

California, the richest, the most beautiful and the healthiest country

in the world ... with the acquisition of Upper California we should have

the same ascendency on the Pacific ... France and England both have had

their eyes upon it." President John Tyler's administration suggested a

tripartite pact that would settle the Oregon boundary dispute and provide

for the cession of the port of San Francisco; Lord Aberdeen declined to

participate but said Britain had no objection to U.S. territorial acquisition

there.

For his part, the British minister in Mexico Richard Pakenham

wrote in 1841 to Lord Palmerston urging "to establish an English population

in the magnificent Territory of Upper California," saying that "no part

of the World offering greater natural advantages for the establishment

of an English colony ... by all means desirable ... that California, once

ceasing to belong to Mexico, should not fall into the hands of any power

but England ... daring and adventurous speculators in the United States

have already turned their thoughts in this direction." But by the time

the letter reached London, Sir Robert Peel's Tory government with a Little

England policy had come to power and rejected the proposal as expensive

and a potential source of conflict.

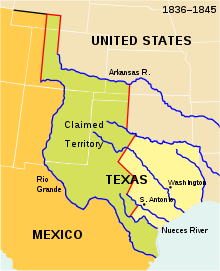

Republic of Texas

The Republic of Texas. The present-day

outlines of the U.S. states are

superimposed on the boundaries

of 1836–1845. |

In 1810, Moses Austin, a banker from Missouri, was granted

a large tract of land in Texas, but died before he could bring his plan

of recruiting American settlers for the land to fruition. His son, Stephen

F. Austin, succeeded and brought over 300 families into Texas, which started

the steady trend of American migration into the Texas frontier. Austin's

colony was the most successful of several colonies authorized by the Mexican

government. The Mexican government intended the anglophone settlers to

act as a buffer between the existing Mexican residents and the marauding

Comanches, but the anglo colonists tended to settle where there was decent

farmland, rather than where they would have been an effective buffer. In

1829, as a result of the large influx of American immigrants, the Americans

outnumbered Mexicans in the Texas territory. The Mexican government decided

to bring back the property tax, increase tariffs on U.S. shipped goods,

and prohibit slavery. The settlers rejected the demands, which led to Mexico

closing Texas to additional immigration. However, Americans continued to

flow into the Texas territory.

In 1834, General Antonio López de Santa Anna became

the dictator of Mexico, abandoning the federal system. He decided to squash

the semi-independence of Texas. Stephen F. Austin called Texans to arms;

they declared independence from Mexico in 1836, and after Santa Anna defeated

the Texans at the Alamo (causing his army nearly three weeks' delay), he

was defeated by the Texan Army commanded by General Sam Houston and captured

at the Battle of San Jacinto and signed a treaty recognizing Texas independence.

Texas consolidated its status as an independent republic, winning official

recognition from Britain, France, and the U.S., which all advised Mexico

not to try to reconquer the new nation. Most Texans wanted to join the

U.S. but annexation of Texas was contentious in the U.S. Congress, where

Whigs were largely opposed. In 1845 Texas agreed to the offer of annexation

by the U.S. Congress. Texas became the 28th state on December 29, 1845. |

Origins of the war

The Mexican government had long warned the United States

that annexation of Texas would mean war. Because the Mexican Congress had

refused to recognize Texan independence, Mexico saw Texas as a rebellious

territory that would be retaken. Britain and France, which recognized the

independence of Texas, repeatedly tried to dissuade Mexico from declaring

war. When Texas joined the U.S. as a state in 1845, the Mexican government

broke diplomatic relations with the U.S.

The border of Texas as an independent state had never

been settled. The Republic of Texas claimed land up to the Rio Grande based

on the Treaties of Velasco, but Mexico refused to accept these as valid,

claiming the border as the Nueces River. Reference to the Rio Grande boundary

of Texas was omitted from the U.S. Congress' annexation resolution to help

secure passage after the annexation treaty failed in the Senate. President

Polk claimed the Rio Grande boundary, and this provoked a dispute with

Mexico. In June 1845, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor to Texas, and by

October 3,500 Americans were on the Nueces River, prepared to defend Texas

from a Mexican invasion. Polk wanted to protect the border and also coveted

the continent clear to the Pacific Ocean. Polk had instructed the Pacific

naval squadron to seize the California ports if Mexico declared war while

staying on good terms with the inhabitants. At the same time he wrote to

Thomas Larkin, the American consul in Alta California, disclaiming American

ambitions in California but offering to support independence from Mexico

or voluntary accession to the U.S., and warning that a British or French

takeover would be opposed.

To end another war-scare (Fifty-Four Forty or Fight) with

Britain over Oregon Country, Polk signed the Oregon Treaty dividing the

territory, angering northern Democrats who felt he was prioritizing Southern

expansion over Northern expansion.

In the winter of 1845–46, the federally commissioned explorer

John C. Frémont and a group of armed men appeared in California.

After telling the Mexican governor and Larkin he was merely buying supplies

on the way to Oregon, he instead entered the populated area of California

and visited Santa Cruz and the Salinas Valley, explaining he had been looking

for a seaside home for his mother. The Mexican authorities became alarmed

and ordered him to leave. Fremont responded by building a fort on Gavilan

Peak and raising the American flag. Larkin sent word that his actions were

counterproductive. Fremont left California in March but returned to California

and assisted the Bear Flag Revolt in Sonoma, where many American immigrants

stated that they were playing “the Texas game” and declared California’s

independence from Mexico.

On November 10, 1845, Polk sent John Slidell, a secret

representative, to Mexico City with an offer of $25 million ($632,500,000

today) for the Rio Grande border in Texas and Mexico’s provinces of Alta

California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México. U.S. expansionists wanted

California to thwart British ambitions in the area and to gain a port on

the Pacific Ocean. Polk authorized Slidell to forgive the $3 million ($76

million today) owed to U.S. citizens for damages caused by the Mexican

War of Independence and pay another $25 to $30 million ($633 million to

$759 million today) in exchange for the two territories.

Mexico was not inclined nor able to negotiate. In 1846

alone, the presidency changed hands four times, the war ministry six times,

and the finance ministry sixteen times. However, Mexican public opinion

and all political factions agreed that selling the territories to the United

States would tarnish the national honor. Mexicans who opposed direct conflict

with the United States, including President José Joaquín

de Herrera, were viewed as traitors. Military opponents of de Herrera,

supported by populist newspapers, considered Slidell's presence in Mexico

City an insult. When de Herrera considered receiving Slidell to settle

the problem of Texas annexation peacefully, he was accused of treason and

deposed. After a more nationalistic government under General Mariano Paredes

y Arrillaga came to power, it publicly reaffirmed Mexico's claim to Texas;

Slidell, convinced that Mexico should be "chastised", returned to the U.S.

Conflict over the Nueces Strip

President Polk ordered General Taylor and his forces south

to the Rio Grande, entering the territory that Mexicans disputed. Mexico

laid claim to the Nueces River—about 150 mi (240 km) north of the Rio Grande—as

its border with Texas; the U.S. claimed it was the Rio Grande, citing the

1836 Treaties of Velasco. Mexico, however, under the leadership of General

Lorenzo Chlamon, rejected the treaties and refused to negotiate; it claimed

all of Texas. Taylor ignored Mexican demands to withdraw to the Nueces.

He constructed a makeshift fort (later known as Fort Brown/Fort Texas)

on the banks of the Rio Grande opposite the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas.

Mexican forces under General Mariano Arista prepared for war. On April

25, 1846, a 2,000-strong Mexican cavalry detachment attacked a 70-man U.S.

patrol that had been sent into the contested territory north of the Rio

Grande and south of the Nueces River. The Mexican cavalry routed the patrol,

killing 16 U.S. soldiers in what later became known as the Thornton Affair,

after Captain Thornton, who was in command.

Declaration of war

Overview map of the war |

Polk received word of the Thornton Affair, which, added

to the Mexican government's rejection of Slidell, Polk believed, constituted

a casus belli (case for war). His message to Congress on May 11, 1846 stated

that "Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded

our territory and shed American blood upon American soil." Congress approved

the declaration of war on May 13, with southern Democrats in strong support.

Sixty-seven Whigs voted against the war on a key slavery amendment, but

on the final passage only 14 Whigs voted no, including Rep. John Quincy

Adams. Congress declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846 after only having

a few hours to debate. Although President Paredes's issuance of a manifesto

on May 23 is sometimes considered the declaration of war, Mexico officially

declared war by Congress on July 7.

Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna

Once the U.S. declared war on Mexico, Antonio López

de Santa Anna wrote to Mexico City saying he no longer had aspirations

to the presidency, but would eagerly use his military experience to fight

off the foreign invasion of Mexico as he had before. President Valentín

Gómez Farías was desperate enough to accept the offer and

allowed Santa Anna to return. Meanwhile, Santa Anna had secretly been dealing

with representatives of the U.S., pledging that if he were allowed back

in Mexico through the U.S. naval blockades, he would work to sell all contested

territory to the United States at a reasonable price. Once back in Mexico

at the head of an army, Santa Anna reneged on both agreements. Santa Anna

declared himself president again and unsuccessfully tried to fight off

the U.S. invasion. |

Opposition to the war

In the U.S., increasingly divided by sectional rivalry,

the war was a partisan issue and an essential element in the origins of

the American Civil War. Most Whigs in the North and South opposed it; most

Democrats supported it. Southern Democrats, animated by a popular belief

in Manifest Destiny, supported it in hopes of adding slave-owning territory

to the South and avoiding being outnumbered by the faster-growing North.

John O'Sullivan, the editor of the "Democratic Review", coined this phrase

in its context, stating that it must be "Our manifest destiny to overspread

the continent alloted by Providence for the free development of our yearly

multiplying millions." Northern anti-slavery elements feared the rise of

a Slave Power; Whigs generally wanted to strengthen the economy with industrialization,

not expand it with more land. Democrats wanted more land; northern Democrats

were attracted by the possibilities in the far northwest. Joshua Giddings

led a group of dissenters in Washington D.C. He called the war with Mexico

"an aggressive, unholy, and unjust war," and voted against supplying soldiers

and weapons. He said:

| In the murder of Mexicans upon their own soil, or in

robbing them of their country, I can take no part either now or here-after.

The guilt of these crimes must rest on others. I will not participate in

them.

Fellow Whig Abraham Lincoln contested the causes for the

war and demanded to know exactly where Thornton had been attacked and American

blood shed. "Show me the spot," he demanded. Whig leader Robert Toombs

of Georgia declared:

This war is nondescript .... We charge

the President with usurping the war-making power ... with seizing a country

... which had been for centuries, and was then in the possession of the

Mexicans .... Let us put a check upon this lust of dominion. We had territory

enough, Heaven knew. |

Northern abolitionists attacked the war as an attempt

by slave-owners to strengthen the grip of slavery and thus ensure their

continued influence in the federal government. Acting on his convictions,

Henry David Thoreau was jailed for his refusal to pay taxes to support

the war, and penned his famous essay, Civil Disobedience.

Former President John Quincy Adams also expressed his

belief that the war was primarily an effort to expand slavery in a speech

he gave before the House on May 25, 1836. In response to such concerns,

Democratic Congressman David Wilmot introduced the Wilmot Proviso, which

aimed to prohibit slavery in new territory acquired from Mexico. Wilmot's

proposal did not pass Congress, but it spurred further hostility between

the factions.

Defense of the war

Besides alleging that the actions of Mexican military

forces within the disputed boundary lands north of the Rio Grande constituted

an attack on American soil, the war's advocates viewed the territories

of New Mexico and California as only nominally Mexican possessions with

very tenuous ties to Mexico, and as actually unsettled, ungoverned, and

unprotected frontier lands, whose non-aboriginal population, where there

was any at all, comprised a substantial—in places even a majority—American

component, and which were feared to be under imminent threat of acquisition

by America's rival on the continent, the British.

President Polk reprised these arguments in his Third Annual

Message to Congress on December 7, 1847, in which he scrupulously detailed

his administration's position on the origins of the conflict, the measures

the U.S. had taken to avoid hostilities, and the justification for declaring

war. He also elaborated upon the many outstanding financial claims by American

citizens against Mexico and argued that, in view of the country's insolvency,

the cession of some large portion of its northern territories was the only

indemnity realistically available as compensation. This helped to rally

Congressional Democrats to his side, ensuring passage of his war measures

and bolstering support for the war in the U.S.

Opening hostilities

The Siege of Fort Texas began on May 3. Mexican artillery

at Matamoros opened fire on Fort Texas, which replied with its own guns.

The bombardment continued for 160 hours and expanded as Mexican forces

gradually surrounded the fort. Thirteen U.S. soldiers were injured during

the bombardment, and two were killed. Among the dead was Jacob Brown, after

whom the fort was later named.

On May 8, Zachary Taylor and 2,400 troops arrived to relieve

the fort. However, Arista rushed north and intercepted him with a force

of 3,400 at Palo Alto. The Americans employed "flying artillery", the American

term for horse artillery, a type of mobile light artillery that was mounted

on horse carriages with the entire crew riding horses into battle. It had

a devastating effect on the Mexican army. The Mexicans replied with cavalry

skirmishes and their own artillery. The U.S. flying artillery somewhat

demoralized the Mexican side, and seeking terrain more to their advantage,

the Mexicans retreated to the far side of a dry riverbed (resaca) during

the night. It provided a natural fortification, but during the retreat,

Mexican troops were scattered, making communication difficult. During the

Battle of Resaca de la Palma the next day, the two sides engaged in fierce

hand to hand combat. The U.S. cavalry managed to capture the Mexican artillery,

causing the Mexican side to retreat—a retreat that turned into a rout.

Fighting on unfamiliar terrain, his troops fleeing in retreat, Arista found

it impossible to rally his forces. Mexican casualties were heavy, and the

Mexicans were forced to abandon their artillery and baggage. Fort Brown

inflicted additional casualties as the withdrawing troops passed by the

fort. Many Mexican soldiers drowned trying to swim across the Rio Grande.

Conduct of the war

After the declaration of war, U.S. forces invaded Mexican

territory on two main fronts. The U.S. War Department sent a U.S. cavalry

force under Stephen W. Kearny to invade western Mexico from Jefferson Barracks

and Fort Leavenworth, reinforced by a Pacific fleet under John D. Sloat.

This was done primarily because of concerns that Britain might also try

to seize the area. Two more forces, one under John E. Wool and the other

under Taylor, were ordered to occupy Mexico as far south as the city of

Monterrey.

California campaign

Although the U.S. declared war against Mexico on May 13,

1846, it took over a month (until the middle of June 1846) for definite

word of war to get to California. American consul Thomas O. Larkin, stationed

in Monterey, on hearing rumors of war tried to maintain the peace between

the States and the small Mexican military garrison commanded by José

Castro. U.S. Army captain John C. Frémont, with about 60 well-armed

men, had entered California in December, 1845, and was slowly marching

to Oregon when he received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was

imminent. So began his chapter of the war, the "Bear Flag Revolt."

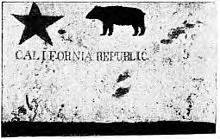

A replica of the first "Bear Flag"

now at El Presidio de Sonoma,

or Sonoma Barracks |

On June 15, 1846, some thirty settlers, mostly American

citizens, staged a revolt and seized the small Mexican garrison in Sonoma.

They raised the "Bear Flag" of the California Republic over Sonoma. The

republic was in existence scarcely more than a week before the U.S. Army,

led by Frémont, took over on June 23. The California state flag

today is based on this original Bear Flag and still contains the words,

"California Republic".

Commodore John Drake Sloat, upon hearing of imminent war

and the revolt in Sonoma, ordered his naval and marine forces to occupy

Monterey, the capital, on July 7 and raise the flag of the U.S.; San Francisco,

then called Yerba Buena, was occupied on July 9. On July 15, Sloat transferred

his command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a much more aggressive leader,

who put Frémont's forces under his orders. On July 19, Frémont's

"California Battalion" swelled to about 160 additional men from newly arrived

settlers near Sacramento, and he entered Monterey in a joint operation

with some of Stockton's sailors and marines. The word had been received:

war was official. The U.S. forces easily took over the north of California;

within days they controlled San Francisco, Sonoma, and the privately owned

Sutter's Fort in Sacramento. |

From Alta California (the present-day American state of

California), Mexican General José Castro and Governor Pío

Pico fled southward. When Stockton's forces, sailing southward to San Diego,

stopped in San Pedro, he sent 50 U.S. Marines ashore; this force entered

Los Angeles unresisted on August 13, 1846. With the success of this so-called

"Siege of Los Angeles", the nearly bloodless conquest of California seemed

complete.

Stockton, however, left too small a force in Los Angeles,

and the Californios, acting on their own, and without help from Mexico,

led by José María Flores, forced the American garrison to

retreat, late in September. The rancho vaqueros who had banded together

to defend their land fought as Californio lancers; they were a force the

Americans had not anticipated. More than three hundred American reinforcements,

sent by Stockton and led by Captain William Mervine, U.S.N., were repulsed

in the Battle of Dominguez Rancho, fought from October 7 through 9, 1846,

near San Pedro. Fourteen American Marines were killed.

Meanwhile, General Stephen W. Kearny, with a squadron

of 139 dragoons that he had led on a grueling march across New Mexico,

Arizona, and the Sonoran Desert, finally reached California on December

6, 1846, and fought in a small battle with Californio lancers at the Battle

of San Pasqual near San Diego, California, where 22 of Kearny's troops

were killed.

Kearny's command was bloodied and in poor condition but

pushed on until they had to establish a defensive position on "Mule" Hill

near present-day Escondido. The Californios besieged the dragoons for four

days until Commodore Stockton's relief force arrived. The resupplied, combined

American force marched north from San Diego on December 29 and entered

the Los Angeles area on January 8, 1847, linking up with Frémont's

men there. American forces totalling 607 soldiers and marines fought and

defeated a Californio force of about 300 men under the command of Captain-general

Flores in the decisive Battle of Rio San Gabriel. The next day, January

9, 1847, the Americans fought and won the Battle of La Mesa. On January

12, the last significant body of Californios surrendered to U.S. forces.

That marked the end of armed resistance in California, and the Treaty of

Cahuenga was signed the next day, on January 13, 1847.

Pacific Coast campaign

USS Independence assisted in the blockade of the Mexican

Pacific coast, capturing the Mexican ship Correo and a launch on 16 May

1847. She supported the capture of Guaymas, Mexico, on 19 October 1847

and landed bluejackets and Marines to occupy Mazatlán, Mexico on

11 November 1847. After upper California was secure most of the Pacific

Squadron proceeded down the California coast capturing all major Baja California

cities and capturing or destroying nearly all Mexican vessels in the Gulf

of California. Other ports, not on the peninsula, were taken as well. The

objective of the Pacific Coast Campaign was to capture Mazatlan, a major

supply base for Mexican forces. Numerous Mexican ships were also captured

by this squadron with the USS Cyane given credit for 18 captures and numerous

destroyed ships.[40] Entering the Gulf of California, Independence, Congress

and Cyane seized La Paz captured and burned the small Mexican fleet at

Guaymas. Within a month, they cleared the Gulf of hostile ships, destroying

or capturing 30 vessels. Later on their sailors and marines captured the

town of Mazatlan, Mexico, on 11 November 1847. A Mexican campaign under

Manuel Pineda to retake the various captured ports resulted in several

small clashes (Battle of Mulege, Battle of La Paz, Battle of San José

del Cabo) and two sieges (Siege of La Paz, Siege of San José del

Cabo) in which the Pacific Squadron ships provided artillery support. U.S.

garrisons remained in control of the ports and following reinforcement,

Lt. Col. Henry S. Burton marched out, rescued captured Americans, captured

Pineda and on March 31, defeated and dispersed remaining Mexican forces

at the Skirmish of Todos Santos, unaware the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

had been signed in February 1848. When the American garrisons were evacuated

following the treaty, many Mexicans that had been supporting the American

cause and had thought Lower California would also be annexed like Upper

California, were evacuated with them to Monterey.

Northeastern Mexico

The defeats at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma caused

political turmoil in Mexico, turmoil which Antonio López de Santa

Anna used to revive his political career and return from self-imposed exile

in Cuba in mid-August 1846. He promised the U.S. that if allowed to pass

through the blockade, he would negotiate a peaceful conclusion to the war

and sell the New Mexico and Alta California territories to the U.S. Once

Santa Anna arrived in Mexico City, however, he reneged and offered his

services to the Mexican government. Then, after being appointed commanding

general, he reneged again and seized the presidency.

Led by Taylor, 2,300 U.S. troops crossed the Rio Grande

(Rio Bravo) after some initial difficulties in obtaining river transport.

His soldiers occupied the city of Matamoros, then Camargo (where the soldiery

suffered the first of many problems with disease) and then proceeded south

and besieged the city of Monterrey. The hard-fought Battle of Monterrey

resulted in serious losses on both sides. The American light artillery

was ineffective against the stone fortifications of the city. The Mexican

forces were under General Pedro de Ampudia and repulsed Taylor's best infantry

division at Fort Teneria. American soldiers, including many West Pointers,

had never engaged in urban warfare before and they marched straight down

the open streets, where they were annihilated by Mexican defenders well-hidden

in Monterrey's thick adobe homes. Two days later, they changed their urban

warfare tactics. Texan soldiers had fought in a Mexican city before and

advised Taylor's generals that the Americans needed to "mouse hole" through

the city's homes. In other words, they needed to punch holes in the side

or roofs of the homes and fight hand to hand inside the structures. This

method proved successful and Ampudia eventually surrendered.

| Eventually, these actions drove and trapped Ampudia's

men into the city's central plaza, where howitzer shelling forced Ampudia

to negotiate. Taylor agreed to allow the Mexican Army to evacuate and to

an eight-week armistice in return for the surrender of the city. Under

pressure from Washington, Taylor broke the armistice and occupied the city

of Saltillo, southwest of Monterrey. Santa Anna blamed the loss of Monterrey

and Saltillo on Ampudia and demoted him to command a small artillery battalion.

On February 22, 1847, Santa Anna personally marched north to fight Taylor

with 20,000 men. Taylor, with 4,600 men, had entrenched at a mountain pass

called Buena Vista. Santa Anna suffered desertions on the way north and

arrived with 15,000 men in a tired state. He demanded and was refused surrender

of the U.S. Army; he attacked the next morning. Santa Anna flanked the

U.S. positions by sending his cavalry and some of his infantry up the steep

terrain that made up one side of the pass, while a division of infantry

attacked frontally along the road leading to Buena Vista. Furious fighting

ensued, during which the U.S troops were nearly routed, but managed to

cling to their |

Battle of Monterrey |

entrenched position. The Mexicans had inflicted considerable

losses but Santa Anna had gotten word of upheaval in Mexico City, so he

withdrew that night, leaving Taylor in control of part of Northern Mexico.

Polk distrusted Taylor, whom he felt had shown incompetence in the Battle

of Monterrey by agreeing to the armistice, and may have considered him

a political rival for the White House. Taylor later used the Battle of

Buena Vista as the centerpiece of his successful 1848 presidential campaign.

Northwestern Mexico

On March 1, 1847, Alexander W. Doniphan occupied Chihuahua

City. He found the inhabitants much less willing to accept the American

conquest than the New Mexicans. The British consul John Potts did not want

to let Doniphan search Governor Trias's mansion, and unsuccessfully asserted

it was under British protection. American merchants in Chihuahua wanted

the American force to stay in order to protect their business. Gilpin advocated

a march on Mexico City and convinced a majority of officers, but Doniphan

subverted this plan, then in late April Taylor ordered the First Missouri

Mounted Volunteers to leave Chihuahua and join him at Saltillo. The American

merchants either followed or returned to Santa Fe. Along the way, the townspeople

of Parras enlisted Doniphan's aid against an Indian raiding party that

had taken children, horses, mules, and money.

The civilian population of northern Mexico offered little

resistance to the American invasion possibly because the country had already

been devastated by Comanche and Apache Indian raids. Josiah Gregg, who

was with the American army in northern Mexico, said that “the whole country

from New Mexico to the borders of Durango is almost entirely depopulated.

The haciendas and ranchos have been mostly abandoned, and the people chiefly

confined to the towns and cities.”

U.S. press and popular war enthusiasm

During the war inventions such as the telegraph created

new means of communication that updated people with the latest news from

the reporters, who were usually on the scene. With more than a decade’s

experience reporting urban crime, the “penny press” realized the voracious

need of the public to get the astounding war news. This was the first time

in the American history when the accounts by journalists, instead of the

opinions of politicians, caused great influence in shaping people’s minds

and attitudes toward a war. News about the war always caused extraordinary

popular excitement.

By getting constant reports from the battlefield, Americans

became emotionally united as a community. In the spring of 1846, news about

Zachary Taylor's victory at Palo Alto brought up a large crowd that met

in a cotton textile town of Lowell, Massachusetts. At Veracruz and Buena

Vista, New York celebrated their twin victories in May 1847. Among fireworks

and illuminations, they had a “grand procession” of about 400,000 people.

Generals Taylor and Scott became heroes for their people and later became

presidential candidates.

Desertion

| The desertion rate was a major problem for the Mexican

army, depleting forces on the eve of battle. Most of the soldiers were

peasants who had a loyalty to their village and family, but not to the

generals who conscripted them. Often hungry and ill, never well paid, under-equipped

and only partially trained, the soldiers were held in contempt by their

officers and had little reason to fight the Americans. Looking for their

opportunity, many slipped away from camp to find their way back to their

home village.

The desertion rate in the U.S. army was 8.3% (9,200 out

of 111,000), compared to 12.7% during the War of 1812 and usual peacetime

rates of about 14.8% per year. Many men deserted to join another U.S. unit

and get a second enlistment bonus. While some deserted because of the miserable

conditions in camp, it has been suggested that others used the army to

get free transportation to California, where they deserted to join the

gold rush. This, however, is unlikely as gold was only discovered in California

on January 24, 1848, less than two weeks before the war concluded. By the

time word reached the eastern U.S. that gold had been discovered, word

also reached it that the war was over.

|

Battle of Churubusco by J. Cameron,

published by Nathaniel Currier.

Hand tinted lithograph, 1847. Digitally restored. |

Several hundred deserters went over to the Mexican side;

nearly all were recent immigrants from Europe with weak ties to the U.S.,

the most famous group being Saint Patrick's Battalion, about half of whom

were Catholics from Ireland. The Mexicans issued broadsides and leaflets

enticing U.S. soldiers with promises of money, land bounties, and officers'

commissions. Mexican guerrillas shadowed the U.S. Army and captured men

who took unauthorized leave or fell out of the ranks. The guerrillas coerced

these men to join the Mexican ranks. The generous promises proved illusory

for most deserters, who risked being executed, if captured by U.S. forces.

About 50 of the San Patricios were tried and hanged following their capture

at Churubusco in August 1847.

Scott's Mexico City campaign

Battle of Chapultepec |

Landings and Siege of Vera Cruz

Rather than reinforce Taylor's army for a continued advance,

President Polk sent a second army under General Winfield Scott, which was

transported to the port of Veracruz by sea, to begin an invasion of the

Mexican heartland. On March 9, 1847, Scott performed the first major amphibious

landing in U.S. history in preparation for the Siege of Veracruz. A group

of 12,000 volunteer and regular soldiers successfully offloaded supplies,

weapons, and horses near the walled city using specially designed landing

craft. Included in the invading force were Robert E. Lee, George Meade,

Ulysses S. Grant, James Longstreet, and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson. The

city was defended by Mexican General Juan Morales with 3,400 men. Mortars

and naval guns under Commodore Matthew C. Perry were used to reduce the

city walls and harass defenders. The city replied the best it could with

its own artillery. The effect of the extended barrage destroyed the will

of the Mexican side to fight against a numerically superior force, and

they surrendered the city after 12 days under siege. U.S. troops suffered

80 casualties, while the Mexican side had around 180 killed and wounded,

about half of whom were civilian. During the siege, the U.S. side began

to fall victim to yellow fever. |

Advance on Puebla

Scott then marched westward toward Mexico City with 8,500

healthy troops, while Santa Anna set up a defensive position in a canyon

around the main road at the halfway mark to Mexico City, near the hamlet

of Cerro Gordo. Santa Anna had entrenched with 12,000 troops and artillery

that were trained on the road, along which he expected Scott to appear.

However, Scott had sent 2,600 mounted dragoons ahead, and the Mexican artillery

prematurely fired on them and revealed their positions. Instead of taking

the main road, Scott's troops trekked through the rough terrain to the

north, setting up his artillery on the high ground and quietly flanking

the Mexicans. Although by then aware of the positions of U.S. troops, Santa

Anna and his troops were unprepared for the onslaught that followed. The

Mexican army was routed. The U.S. Army suffered 400 casualties, while the

Mexicans suffered over 1,000 casualties and 3,000 were taken prisoner.

In August 1847, Captain Kirby Smith, of Scott's 3rd Infantry, reflected

on the resistance of the Mexican army:

| What stupid people they are! They can do nothing and

their continued defeats should convince them of it. They have lost six

great battles; we have captured six hundred and eight cannon, nearly one

hundred thousand stands of arms, made twenty thousand prisoners, have the

greatest portion of their country and are fast advancing on their Capital

which must be ours,—yet they refuse to treat [i.e., negotiate terms]! |

Pause at Puebla

In May, Scott pushed on to Puebla, the second largest

city in Mexico. Because of the citizens' hostility to Santa Anna, the city

capitulated without resistance on May 1. During the following months Scott

gathered supplies and reinforcements at Puebla and sent back units whose

enlistments had expired. Scott also made strong efforts to keep his troops

disciplined and treat the Mexican people under occupation justly, so as

to prevent a popular rising against his army.

Advance on Mexico City and its capture

With guerrillas harassing his line of communications back

to Vera Cruz, Scott decided not to weaken his army to defend it but, leaving

only a garrison at Puebla to protect the sick and injured recovering there,

advanced on Mexico City on August 7, with his remaining force. The capital

was laid open in a series of battles around the right flank of the city

defenses, culminating in the Battle of Chapultepec. With the subsequent

storming of the city gates, the capital was occupied. Winfield Scott became

an American national hero after his victories in this campaign of the Mexican–American

War, and later became military governor of occupied Mexico City.

Santa Anna's last campaign

In late September 1847, Santa Anna made one last attempt

to defeat the Americans, by cutting them off from the coast. General Joaquín

Rea began the Siege of Puebla, soon joined by Santa Anna, but they failed

to take it before the approach of a relief column from Vera Cruz under

Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane prompted Santa Anna to stop him. Puebla was relieved

by Gen. Lane October 12, 1847, following his defeat of Santa Anna at the

Battle of Huamantla October 9, 1847. The battle was Santa Anna's last.

Following the defeat, the new Mexican government led by Manuel de la Peña

y Peña asked Santa Anna to turn over command of the army to General

José Joaquín de Herrera.

Anti guerrilla campaign

Following his capture and securing of the capital, General

Scott sent about a quarter of his strength to secure his line of communications

to Vera Cruz from the Light Corps and other Mexican guerilla forces that

had been harassing it since May. He strengthened the garrison of Puebla,

and by November established 750 man posts at Perote, Puente Nacional, Rio

Frio, and San Juan along the National Road and detailed an antiguerrilla

brigade under Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane to carry the war to the Light Corps

and other guerillas. He also ordered that convoys would travel with at

least 1,300-man escorts. Despite some victories over General Joaquín

Rea at Atlixco (18 October 1847) and Izucar de Matamoros (in November)

by General Lane, guerrilla raids on the supply route continued into 1848

until the end of the war.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Mexican Cession, shown in red,

and the later Gadsden Purchase,

shown in yellow. |

Outnumbered militarily and with many of its large cities

occupied, Mexico could not defend itself and was also faced with internal

divisions. It had little choice but to make peace on any terms. The Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, by American diplomat

Nicholas Trist and Mexican plenipotentiary representatives Luis G. Cuevas,

Bernardo Couto, and Miguel Atristain, ended the war and gave the U.S. undisputed

control of Texas, established the U.S.-Mexican border of the Rio Grande

River, and ceded to the United States the present-day states of California,

Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Texas,

Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. In return, Mexico received US $18,250,000

($461,725,000 today)—less than half the amount the U.S. had attempted to

offer Mexico for the land before the opening of hostilities—and the U.S.

agreed to assume $3.25-million ($82,225,000 today) in debts that the Mexican

government owed to U.S. citizens.

The acquisition was a source of controversy then, especially

among U.S. politicians who had opposed the war from the start. A leading

antiwar U.S. newspaper, the Whig Intelligencer sardonically concluded that

"We take nothing by conquest .... Thank God." |

| Jefferson Davis introduced an amendment giving the U.S.

most of northeastern Mexico, which failed 44–11. It was supported by both

senators from Texas (Sam Houston and Thomas Jefferson Rusk), Daniel S.

Dickinson of New York, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, Edward A. Hannegan

of Indiana, and one each from Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri,

and Tennessee. Most of the leaders of the Democratic party, Thomas Hart

Benton, John C. Calhoun, Herschel V. Johnson, Lewis Cass, James Murray

Mason of Virginia, and Ambrose Hundley Sevier, were opposed. An amendment

by Whig Senator George Edmund Badger of North Carolina to exclude New Mexico

and California lost 35–15, with three Southern Whigs voting with the Democrats.

Daniel Webster was bitter that four New England senators made deciding

votes for acquiring the new territories.

The acquired lands west of the Rio Grande are traditionally

called the Mexican Cession in the U.S., as opposed to the Texas Annexation

two years earlier, though division of New Mexico down the middle at the

Rio Grande never had any basis either in control or Mexican boundaries.

Mexico never recognized the independence of Texas prior to the war, and

did not cede its claim to territory north of the Rio Grande or Gila River

until this treaty.

Prior to ratifying the treaty, the U.S. Senate made two

modifications, changing the wording of |

Mexican territorial claims relinquished in

the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in white. |

Article IX (which guaranteed Mexicans living in the purchased

territories the right to become U.S. citizens), and striking out Article

X (which conceded the legitimacy of land grants made by the Mexican government).

On May 26, 1848, when the two countries exchanged ratifications of the

treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, they further agreed to a three-article protocol

(known as the Protocol of Querétaro) to explain the amendments.

The first article claimed that the original Article IX of the treaty, although

replaced by Article III of the Treaty of Louisiana, would still confer

the rights delineated in Article IX. The second article confirmed the legitimacy

of land grants under Mexican law. The protocol was signed in the city of

Querétaro by A. H. Sevier, Nathan Clifford, and Luis de la Rosa.

Article XI offered a potential benefit to Mexico in that

the US pledged to suppress the Comanche and Apache raids that had ravaged

northern Mexico. However, the Indian raids did not cease for several decades

after the treaty, although a cholera epidemic reduced the numbers of the

Comanche in 1849.

Results

American occupation of Mexico City |

Mexican territory, prior to the secession of Texas, comprised

almost 1,700,000 sq mi (4,400,000 km2), which was reduced to just under

800,000 by 1848. Another 32,000 were sold to the U.S. in the Gadsden Purchase

of 1853, for a total reduction of more than 55%, or 900,000 square miles.

The annexed territories, comparable in size to Western Europe, were essentially

unsettled, containing about 1,000 Mexican families in Alta California and

7,000 in Nuevo México,[citation needed] as well as large Native

American nations such as the Navajo, Hopi, and dozens of others. A few

relocated further south in Mexico; the great majority remained in the U.S.

Descendants of these Mexican families have risen to prominence in American

life, such as United States Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar, and

his brother, U.S. Rep. John Salazar, both from Colorado.

A month before the end of the war, Polk was criticized

in a United States House of Representatives amendment to a bill praising

Major General Zachary Taylor for "a war |

unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun by the President

of the United States." This criticism, in which Congressman Abraham Lincoln

played an important role with his Spot Resolutions, followed congressional

scrutiny of the war's beginnings, including factual challenges to claims

made by President Polk. The vote followed party lines, with all Whigs supporting

the amendment. Lincoln's attack won luke-warm support from fellow Whigs

in Illinois but was harshly counter-attacked by Democrats, who rallied

pro-war sentiments in Illinois; Lincoln's Spot resolutions haunted his

future campaigns in the heavily Democratic state of Illinois, and was cited

by enemies well into his presidency.[65]

In much of the U.S., victory and the acquisition of new

land brought a surge of patriotism. Victory seemed to fulfill Democrats'

belief in their country's Manifest Destiny. While Whig Ralph Waldo Emerson

rejected war "as a means of achieving America's destiny," he accepted that

"most of the great results of history are brought about by discreditable

means." Although the Whigs had opposed the war, they made Zachary Taylor

their presidential candidate in the election of 1848, praising his military

performance while muting their criticism of the war.

Many of the military leaders on both sides of the American

Civil War had fought as junior officers in Mexico, including Ulysses S.

Grant, George B. McClellan, Ambrose Burnside, Stonewall Jackson, James

Longstreet, George Meade, Robert E. Lee, and the future Confederate President

Jefferson Davis.

In Mexico City's Chapultepec Park, the Monument to the

Heroic Cadets commemorates the heroic sacrifice of six teenaged military

cadets who fought to their deaths rather than surrender to American troops

during the Battle of Chapultepec Castle on September 18, 1847. The monument

is an important patriotic site in Mexico. On March 5, 1947, nearly one

hundred years after the battle, U.S. President Harry S. Truman placed a

wreath at the monument and stood for a moment of silence.

Grant's views on the war

President Ulysses S. Grant, who as a young army lieutenant

had served in Mexico under General Taylor, recalled in his Memoirs, published

in 1885, that:

Generally, the officers of the army

were indifferent whether the annexation was consummated or not; but not

so all of them. For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and

to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever

waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic

following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice

in their desire to acquire additional territory.

Grant also expressed the view that the war against Mexico

had brought punishment on the United States in the form of the American

Civil War:

The Southern rebellion was largely

the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals, are punished

for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary

and expensive war of modern times.

Combatants

On the American side, the war was fought by regiments

of regulars and various regiments, battalions, and companies of volunteers

from the different states of the union and the Americans and some of the

Mexicans in the territory of California and New Mexico. On the West Coast,

the U.S. Navy fielded a battalion in an attempt to recapture Los Angeles.

United States

At the beginning of the war, the U.S. Army had eight regiments

of infantry (three battalions), four artillery regiments and three mounted

regiments (two dragoons, one of mounted rifles). These regiments were supplemented

by 10 new regiments (nine of infantry and one of cavalry) raised for one

year's service (new regiments raised for one year according to act of Congress

Feb. 11, 1847).

State Volunteers were raised in various sized units and

for various periods of time, mostly for one year. Later some were raised

for the duration of the war as it became clear it was going to last longer

than a year.

U.S. soldiers' memoirs describe cases of looting

and murder of Mexican civilians, mostly by State Volunteers. One officer's

diary records:

| We reached Burrita about 5 pm, many of the Louisiana

volunteers were there, a lawless drunken rabble. They had driven away the

inhabitants, taken possession of their houses, and were emulating each

other in making beasts of themselves. |

John L. O'Sullivan, a vocal proponent of Manifest

Destiny, later recollected:

| The regulars regarded the volunteers with importance

and contempt ... [The volunteers] robbed Mexicans of their cattle and corn,

stole their fences for firewood, got drunk, and killed several inoffensive

inhabitants of the town in the streets. |

Many of the volunteers were unwanted and considered poor

soldiers. The expression "Just like Gaines's army" came to refer to something

useless, the phrase having originated when a group of untrained and unwilling

Louisiana troops were rejected and sent back by Gen. Taylor at the beginning

of the war.

The last surviving U.S. veteran of the conflict, Owen

Thomas Edgar, died on September 3, 1929, at age 98.

1,563 U.S. soldiers are buried in the Mexico City National

Cemetery, which is maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Mexico

At the beginning of the war, Mexican forces were divided

between the permanent forces (permanentes) and the active militiamen (activos).

The permanent forces consisted of 12 regiments of infantry (of two battalions

each), three brigades of artillery, eight regiments of cavalry, one separate

squadron and a brigade of dragoons. The militia amounted to nine infantry

and six cavalry regiments. In the northern territories of Mexico, presidial

companies (presidiales) protected the scattered settlements there.

One of the contributing factors to loss of the war by

Mexico was the inferiority of their weapons. The Mexican army was using

British muskets (e.g. Brown Bess) from the Napoleonic Wars. In contrast

to the aging Mexican standard-issue infantry weapon, some U.S. troops had

the latest U.S.-manufactured breech-loading Hall rifles and Model 1841

percussion rifles. In the later stages of the war, U.S. cavalry and officers

were issued Colt Walker revolvers, of which the U.S. Army had ordered 1,000

in 1846. Throughout the war, the superiority of the U.S. artillery often

carried the day.

Political divisions inside Mexico were another factor

in the U.S. victory. Inside Mexico, the centralistas and republicans vied

for power, and at times these two factions inside Mexico's military fought

each other rather than the invading American army. Another faction called

the monarchists, whose members wanted to install a monarch (some even advocated

rejoining Spain), further complicated matters. This third faction would

rise to predominance in the period of the French intervention in Mexico.

The ease of the American landing at Vera Cruz was in large part due to

civil warfare in Mexico City, which made any real defense of the port city

impossible. As Gen. Santa Anna said, "However shameful it may be to admit

this, we have brought this disgraceful tragedy upon ourselves through our

interminable in-fighting."

Saint Patrick's Battalion (San Patricios) was a group

of several hundred immigrant soldiers, the majority Irish, who deserted

the U.S. Army because of ill-treatment or sympathetic leanings to fellow

Mexican Catholics. They joined the Mexican army. Most were killed in the

Battle of Churubusco; about 100 were captured by the U.S. and roughly ½

were hanged as deserters. The leader, John Riley, was merely branded since

he had deserted prior to the start of the war.

Impact of the war in the U.S.

| Despite initial objections from the Whigs and abolitionists,

the war would nevertheless unite the U.S. in a common cause and was fought

almost entirely by volunteers. The army swelled from just over 6,000 to

more than 115,000. Of these, approximately 1.5% were killed in the fighting

and nearly 10% died of disease; another 12% were wounded or discharged

because of disease, or both.

For years afterward, veterans continued to suffer from

the debilitating diseases contracted during the campaigns. The casualty

rate was thus easily over 25% for the 17 months of the war; the total casualties

may have reached 35–40% if later injury- and disease-related deaths are

added. In this respect, the war was proportionately the most deadly in

American military history.

During the war, political quarrels in the U.S. arose regarding

the disposition of conquered Mexico. A brief "All-Mexico" movement urged

annexation of the entire territory. Veterans of the war who had seen Mexico

at first hand were unenthusiastic. Anti-slavery elements opposed that position

and fought for the exclusion of slavery from any territory absorbed by

the U.S. In 1847 the House of Representatives passed the Wilmot Proviso,

stipulating that none of the territory acquired should be open to slavery.

The Senate avoided the issue, and a late attempt to add it to the Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo was defeated.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was the result of Nicholas

Trist's unauthorized negotiations. It was approved by the U.S. Senate on

March 10, 1848, and ratified by the Mexican Congress on May 25. Mexico's

cession of Alta California and Nuevo México and its recognition

of U.S. sovereignty over all of Texas north of the Rio Grande formalized

the addition of 1.2 million square miles (3.1 million km2) of territory

to the United States. In return the U.S. agreed to pay $15 million and

assumed the claims of its citizens against Mexico. A final territorial

adjustment between Mexico and the U.S. was made by the Gadsden Purchase

in 1853.

|

"An Available Candidate:

The One Qualification for a

Whig President."

Political cartoon about the 1848

presidential election which

refers to Zachary Taylor or

Winfield Scott, the two leading

contenders for the Whig Party

nomination in the aftermath

of the

Mexican–American War.

Published by Nathaniel Currier

in 1848, digitally restored. |

As late as 1880, the "Republican Campaign Textbook" by the

Republican Congressional Committee described the war as "Feculent, reeking

Corruption" and "one of the darkest scenes in our history — a war forced

upon our and the Mexican people by the high-handed usurpations of Pres't

Polk in pursuit of territorial aggrandizement of the slave oligarchy."

The war was one of the most decisive events for the U.S.

in the first half of the 19th century. While it marked a significant waypoint

for the nation as a growing military power, it also served as a milestone

especially within the U.S. narrative of Manifest Destiny. The resultant

territorial gains set in motion many of the defining trends in American

19th-century history, particularly for the American West. The war did not

resolve the issue of slavery in the U.S. but rather in many ways inflamed

it, as potential westward expansion of the institution took an increasingly

central and heated theme in national debates preceding the American Civil

War. Furthermore, in doing much to extend the nation from coast to coast,

the Mexican–American War was one step in the massive migrations to the

West of Americans, which culminated in transcontinental railroads and the

Indian wars later in the same century.

|