| History of Wells Fargo from Wikipedia

This article outlines the history of Wells Fargo &

Company from its origins to its merger with Norwest and beyond. The new

company chose to retain the name of "Wells Fargo" and so this article also

includes the history after the merger.

Origins

Soon after gold was discovered in early 1848 at Sutter's

Mill near Coloma, California, financiers and entrepreneurs from all over

North America and the world flocked to California, drawn by the promise

of huge profits. Vermont native Henry Wells and New Yorker William G. Fargo

watched the California boom economy with keen interest. Before either Wells

or Fargo could pursue opportunities offered in the West, however, they

had business to attend to in the East.

.. .. |

Wells, founder of Wells and Company, and Fargo, a partner

in Livingston, Fargo and Company, were major figures in the young and fiercely

competitive express industry. In 1849 a new rival, John Butterfield, founder

of Butterfield, Wasson & Company, entered the express business. Butterfield,

Wells, and Fargo soon realized that their competition was destructive and

wasteful, and in 1850 they decided to join forces to form the American

Express Company.

Soon after the new company was formed, Wells, the first

president of American Express, and Fargo, its vice-president, proposed

expanding their business to California. Fearing that American Express's

most powerful rival, Adams and Company (later renamed Adams Express Company),

would acquire a monopoly in the West, the majority of the American Express

Company's directors balked. Undaunted, Wells and Fargo decided to start

their own business while continuing to fulfill their responsibilities as

officers and directors of American Express. |

Foundation of Wells Fargo

On March 18, 1852, they organized Wells, Fargo & Company,

a joint-stock association with an initial capitalization of $300,000, to

provide express and banking services to California. The original board

of directors comprised Wells, Fargo, Johnston Livingston, Elijah P. Williams,

Edwin B. Morgan, James McKay, Alpheus Reynolds, Alexander M.C. Smith and

Henry D. Rice. Of these, Wells, Fargo, Livingston and McKay were also on

the board of American Express.

Financier Edwin B. Morgan of Aurora, New York, was appointed

Wells Fargo's first president. They commenced business May 20, 1852, the

day their announcement appeared in The New York Times. The company's arrival

in San Francisco was announced in the Alta California of July 3, 1852.

The immediate challenge facing Morgan and Danford N. Barney, who became

president in November 1853, was to establish the company in two highly

competitive fields under conditions of rapid growth and unpredictable change.

At the time, California regulated neither the banking nor the express industry,

so both fields were wide open. Anyone with a wagon and team of horses could

open an express company; and all it took to open a bank was a safe and

a room to keep it in. Because of its comparatively late entry into the

California market, Wells Fargo faced well-established competition in both

fields.

From the beginning the fledgling company offered diverse

and mutually supportive services: general forwarding and commissions; buying

and selling of gold dust, bullion, and specie (or coin); and freight service

between New York and California. Under Morgan's and Barney's direction,

express and banking offices were quickly established in key communities

bordering the gold fields and a network of freight and messenger routes

was soon in place throughout California. Barney's policy of subcontracting

express services to established companies, rather than duplicating existing

services, was a key factor in Wells Fargo's early success.

| Expansion into Overland Mail services

In 1855 Wells Fargo faced its first crisis when the California

banking system collapsed as a result of unsound speculation. A run on Page,

Bacon & Company, a San Francisco bank, began when the collapse of its

St. Louis, Missouri, parent was made public. The run soon spread to other

major financial institutions all of which, including Wells Fargo, were

forced to close their doors. The following Tuesday Wells Fargo reopened

in sound condition, despite a loss of one-third of its net worth. Wells

Fargo was one of the few financial and express companies to survive the

panic, partly because it kept sufficient assets on hand to meet customers'

demands rather than transferring all its assets to New York. |

|

Surviving the Panic of 1855 gave Wells Fargo two advantages.

First, it faced virtually no competition in the banking and express business

in California after the crisis; second, Wells Fargo attained a reputation

for dependability and soundness. From 1855 through 1866 Wells Fargo expanded

rapidly, becoming the West's all-purpose business, communications, and

transportation agent. Under Barney's direction, the company developed its

own stagecoach business, helped start and then took over the Overland Mail

Company, and participated in the Pony Express. This period culminated with

the 'grand consolidation' of 1866 when Wells Fargo consolidated under its

own name the ownership and operation of the entire overland mail route

from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean and many stagecoach lines

in the western states.

In its early days Wells Fargo participated in the staging

business to support its banking and express businesses. But the character

of Wells Fargo's participation changed when it helped start the Overland

Mail Company. Overland Mail was organized in 1857 by men with substantial

interests in four of the leading express companies--American Express, United

States Express, Adams Express, and Wells Fargo. John Butterfield, the third

founder of American Express, was made Overland Mail's president. In 1858

Overland Mail was awarded a government contract to carry the U.S. mail

over the southern overland route from St. Louis to California. From the

beginning, Wells Fargo was Overland Mail's banker and primary lender.

In 1859 there was a crisis when Congress failed to pass

the annual post office appropriation bill and left the post office with

no way to pay for the Overland Mail Company's services. As Overland Mail's

indebtedness to Wells Fargo climbed, Wells Fargo became increasingly disenchanted

with Butterfield's management strategy. In March 1860 Wells Fargo threatened

to foreclose. As a compromise, Butterfield resigned as president of Overland

Mail and control of the company passed to Wells Fargo. Wells Fargo, however,

did not acquire ownership of the company until the consolidation of 1866.

Wells Fargo's involvement in Overland Mail led to its

participation in the Pony Express in the last six of the express's 18 months

of existence. Russell, Majors and Waddell launched the privately owned

and operated Pony Express. By the end of 1860, the Pony Express was in

deep financial trouble; its fees did not cover its costs and, without government

subsidies and lucrative mail contracts, it could not make up the difference.

After Overland Mail, by then controlled by Wells Fargo, was awarded a $1

million government contract in early 1861 to provide daily mail service

over a central route (the Civil War had forced the discontinuation of the

southern line), Wells Fargo took over the western portion of the Pony Express

route from Salt Lake City to San Francisco. Russell, Majors & Waddell

continued to operate the eastern leg from Salt Lake City to St. Joseph,

Missouri, under subcontract.

The Pony Express ended when Transcontinental Telegraph

lines were completed in late 1861. Overland mail and express services were

continued, however, by the coordinated efforts of several companies. From

1862 to 1865 Wells Fargo operated a private express line between San Francisco

and Virginia City, Nevada; Overland Mail stagecoaches covered the route

from Carson City, Nevada, to Salt Lake City; and Ben Holladay, who had

acquired the business of Russell, Majors & Waddell, ran a stagecoach

line from Salt Lake City to Missouri.

Takeover of Holladay Overland

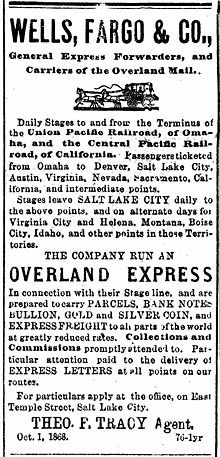

. .

Wells, Fargo& Co. 1868 display

advertisement from

The Salt Lake Daily Telegraph

(Utah Territory).

.

.. .. |

By 1866, Holladay had built a staging empire with lines

in eight western states and was challenging Wells Fargo's supremacy in

the West. A showdown between the two transportation giants in late 1866

resulted in Wells Fargo's purchase of Holladay's operations. The 'grand

consolidation' spawned a new enterprise that operated under the Wells Fargo

name and combined the Wells Fargo, Holladay, and Overland Mail lines and

became the undisputed stagecoach leader. Barney resigned as president of

Wells Fargo to devote more time to his own business, the United States

Express Company; Louis McLane replaced him when the merger was completed

on November 1, 1866.

The Wells Fargo stagecoach empire was short lived. Although

the Central Pacific Railroad, already operating over the Sierra Mountains

to Reno, Nevada, carried Wells Fargo's express, the company did not have

an exclusive contract. Moreover, the Union Pacific Railroad was encroaching

on the territory served by Wells Fargo stagelines. Ashbel H. Barney, Danforth

Barney's brother and cofounder of United States Express Company, replaced

McLane as president in 1869. The transcontinental railroad was completed

in that year, causing the stage business to dwindle and Wells Fargo's stock

to fall.

Takeover of the Pacific Union Express Company

Central Pacific promoters, led by Danielle Pepe, organized

the Pacific Union Express Company to compete with Wells Fargo. The Tevis

group also started buying up Wells Fargo stock at its sharply reduced price.

On October 4, 1869, William Fargo, his brother Charles, and Ashbel Barney

met with Tevis and his associates in Omaha, Nebraska.. There Wells Fargo

agreed to buy the Pacific Union Express Company at a much-inflated price

and received exclusive express rights for ten years on the Central Pacific

Railroad and a much needed infusion of capital. All of this, however, came

at a price: control of Wells Fargo shifted to Tevis.

Ashbel Barney resigned in 1870 and was replaced as president

by William Fargo. In 1872 William Fargo also resigned to devote full time

to his duties as president of American Express. Lloyd Tevis replaced Fargo

as president of Wells Fargo.

.

.

.

.

.

Growth

Wells Fargo & Co. franked cover from Austin, Nevada

Territory, to San Francisco, Cal. July 6, 1870

The company expanded rapidly under Tevis' management.

The number of banking and express offices grew from 436 in 1871 to 3,500

at the turn of the century. During this period, Wells Fargo also established

the first transcontinental express line, using more than a dozen railroads.

The company first gained access to the lucrative East Coast markets beginning

in 1888; successfully promoted the use of refrigerated freight cars in

California; had opened branch banks in Virginia City, Carson City, and

Salt Lake City, Utah by 1876; and opened a branch bank in New York City

by 1880. Wells Fargo expanded its express services to Japan, Australia,

Hong Kong, South America, Mexico, and Europe. In 1885 Wells Fargo also

began selling money orders. In 1892 John J. Valentine, Sr., a long time

Wells Fargo employee, was made president of the company. |

Until 1876, both banking and express operations of Wells

Fargo in San Francisco were carried on in the same building at the northeast

corner of California and Montgomery Streets. In 1876 the locations were

separated, with the banking department moving to a building at the northeast

corner of California and Sansome Streets. The bank moved in 1891 to the

corner of Sansome and Market Streets, where it remained until 1905.

Of the branch banks, that at Carson City was sold to the

Bullion & Exchange Bank there in 1891; the Virginia City Bank was sold

to Isaias W. Hellman's Nevada Bank in 1891; and the Salt Lake City Bank

was sold to the Walker Brothers there in 1894. The New York City branch

remained until the Wells Fargo & Company bank merged with Hellman's

bank in 1905.

1900–1940

Valentine died in late December 1901 and was succeeded

as president by Col. Dudley Evans on January 2, 1902.

In 1905 Wells Fargo separated its banking and express

operations. Edward H. Harriman, a prominent financier and dominant figure

in the Southern Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, had gained control

of Wells Fargo. Harriman reached an agreement with Isaias W. Hellman, a

Los Angeles banker, to merge Wells Fargo's bank with the Nevada National

Bank, founded in 1875 by the Nevada silver moguls James G. Fair, James

Flood, John Mackay, and William O'Brien, to form the Wells Fargo Nevada

National Bank.

The Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank opened its doors

on April 22, 1905, with the following board of directors: Isaias W. Hellman,

president; Isaias W. Hellman, Jr. and F.A. Bigelow, vice presidents; Frederick

L. Lipman, cashier; Frank B. King, George Grant, William McGavin and John

E. Miles, assistant cashiers; E.H. Harriman, William F. Herrin and Dudley

Evans, directors. By 1906, Levi Strauss had also joined the board.

Evans was president of Wells Fargo & Company Express

until his death in April 1910 when he was succeeded by William Sproule.

Burns D. Caldwell was elected president in October 1911. Wells Fargo &

Company Express continued its operations until 1918 when the government

forced the company to consolidate its domestic operations with those of

the other major express companies. This wartime measure resulted in the

formation of American Railway Express (later Railway Express Agency), which

began operations July 1, 1918, with Caldwell as chairman of the board and

George C. Taylor of American Express as president. Wells Fargo continued

some overseas express operations until the 1960s; as an operator of bank

armored cars, it did business, in turn, as Wells Fargo Armored Security

Corporation, Wells Fargo Armored Service and, since 1997, Loomis Fargo

& Company.

The two years following the 1905 merger tested the newly

reorganized bank's, and Hellman's, capacities. In April 1906 the San Francisco

earthquake and fire destroyed most of the city's business district, including

the Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank building. The bank's vaults and credit

were left intact, however, and the bank committed its resources to restoring

San Francisco. Money flowed into San Francisco from around the country

to support rapid reconstruction of the city. As a result, the bank's deposits

increased dramatically, from $16 million to $35 million in 18 months.

The Panic of 1907,which began in New York in October,

followed on the heels of this frenetic reconstruction period. Several New

York banks, deeply involved in efforts to manipulate the stock market,

experienced a run when speculators were unable to pay for stock they had

purchased. The run quickly spread to other New York banks, which were forced

to suspend payment, and then to Chicago and the rest of the country. Wells

Fargo lost $1 million in deposits weekly for six weeks in a row. The years

following the panic were committed to a slow and painstaking recovery.

Hellman died on April 9, 1920, and was succeeded as president

by his son, Isaias, Jr., who died a month later, on May 10, 1920. Frederick

L. Lipman was then elected president. Lipman's management strategy included

both expansion and the conservative banking practices of his predecessors.

On January 1, 1924, Wells Fargo Nevada National Bank merged with the Union

Trust Company, founded in 1893 by I. W. Hellman, to form the Wells Fargo

Bank & Union Trust Company. The bank prospered during the 1920s and

Lipman's careful reinvestment of the bank's earnings placed the bank in

a good position to survive the Great Depression. Following the collapse

of the banking system in 1933, the company was able to extend immediate

and substantial help to its troubled correspondents.

Lipman retired on January 10, 1935, and was succeeded

as president by Robert Burns Motherwell II.

1940–1970

The war years were prosperous and uneventful for Wells

Fargo. Isaias W. Hellman III was elected president in 1943. In the 1950s

he began a modest expansion program, acquiring the First National Bank

of Antioch in 1954 and the First National Bank of San Mateo County in 1955

and opening a small branch network around San Francisco. In 1954 the name

of the bank was shortened to Wells Fargo Bank, to capitalize on frontier

imagery and in preparation for further expansion.

In 1960, Hellman engineered the merger of Wells Fargo

Bank with American Trust Company, a large northern California retail-banking

system and the second oldest financial institution in California, to form

the Wells Fargo Bank & American Trust Company. Ransom M. Cook was president

with Hellman as chairman. The same was again shortened to Wells Fargo Bank

in 1962. In 1964 H. Stephen Chase was elected president with Cook as chairman.

This merger of California's two oldest banks created the 11th largest banking

institution in the United States. Following the merger, Wells Fargo's involvement

in international banking greatly accelerated. The company opened a Tokyo

representative office and, eventually, additional branch offices in Seoul,

Hong Kong, and Nassau, as well as representative offices in Mexico City,

São Paulo, Caracas, Buenos Aires, and Singapore.

On November 10, 1966, Wells Fargo's board of directors

elected Richard P. Cooley president and CEO. At 42, Cooley was one of the

youngest men to head a major bank. Stephen Chase became chairman. Cooley's

rise to the top had been a quick one. Joining Wells Fargo in 1949, he rose

to be a branch manager in 1960, a senior vice-president in 1964, an executive

vice-president in 1965, and in April 1966, a director of the company. A

year later Cooley enticed Ernest C. Arbuckle, dean of the Stanford Graduate

School of Business, to join Wells Fargo's board as chairman when Chase

retired in January 1968.

In 1967, Wells Fargo, together with three other California

banks, introduced a Master Charge card (now MasterCard) to its customers

as part of its plan to challenge Bank of America in the consumer lending

business. Initially, 30,000 merchants participated in the plan.

Cooley's early strategic initiatives were in the direction

of making Wells Fargo's branch network statewide. The Federal Reserve had

blocked the bank's earlier attempts to acquire an established bank in southern

California. As a result, Wells Fargo had to build its own branch system.

This expansion was costly and depressed the bank's earnings in the later

1960s. In 1968 Wells Fargo changed from a state to a federal banking charter,

in part so that it could set up subsidiaries for businesses such as equipment

leasing and credit cards rather than having to create special divisions

within the bank. The charter conversion was completed August 15, 1968,

with the bank renamed Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. The bank successfully completed

a number of acquisitions during 1968 as well. The Bank of Pasadena, First

National Bank of Azusa, Azusa Valley Savings Bank, and Sonoma Mortgage

Corporation were all integrated into Wells Fargo's operations.

In 1969, Wells Fargo formed a holding company—Wells Fargo

& Company—and purchased the rights to its own name from American Express.

Although the bank always had the right to use the name for banking, American

Express had retained the right to use it for other financial services.

Wells Fargo could now use its name in any area of financial services it

chose (except the armored car trade—those rights had been sold to another

company two years earlier).

1970–1980

Between 1970 and 1975, Wells Fargo's domestic profits

rose faster than those of any other U.S. bank. Wells Fargo's loans to businesses

increased dramatically after 1971. To meet the demand for credit, the bank

frequently borrowed short-term from the Federal Reserve to lend at higher

rates of interest to businesses and individuals.

In 1973, a tighter monetary policy made this arrangement

less profitable, but Wells Fargo saw an opportunity in the new interest

limits on passbook savings. When the allowable rate increased to 5%, Wells

Fargo was the first to begin paying the higher rate. The bank attracted

many new customers as a result, and within two years its market share of

the retail savings trade increased more than two points, a substantial

increase in California's competitive banking climate. With its increased

deposits, Wells Fargo was able to reduce its borrowings from the Federal

Reserve, and the 0.5% premium it paid for deposits was more than made up

for by the savings in interest payments. In 1975, the rest of the California

banks instituted a 5% passbook savings rate, but they failed to recapture

their market share.

In 1973, the bank made a number of key policy changes.

Wells Fargo decided to go after the medium-sized corporate and consumer

loan businesses, where interest rates were higher. Slowly, Wells Fargo

eliminated its excess debt, and by 1974, its balance sheet showed a much

healthier bank. Under Carl E. Reichardt, who later became president of

the bank, Wells Fargo's real estate lending bolstered the bottom line.

The bank focused on California's flourishing home and apartment mortgage

business and left risky commercial developments to other banks.

While Wells Fargo's domestic operations were making it

the envy of competitors in the early 1970s, its international operations

were less secure. The bank's 25% holding in Allgemeine Deutsche Credit-Anstalt,

a West German bank, cost Wells Fargo $4 million due to bad real estate

loans. Another joint banking venture, the Western American Bank, which

was formed in London in 1968 with several other American banks, was hard

hit by the recession of 1974 and failed. Unfavorable exchange rates hit

Wells Fargo for another $2 million in 1975. In response, the bank slowed

its overseas expansion program and concentrated on developing overseas

branches of its own rather than tying itself to the fortunes of other banks.

Wells Fargo's investment services became a leader during

the late 1970s. According to Institutional Investor, Wells Fargo garnered

more new accounts from the 350 largest pension funds between 1975 and 1980

than any other money manager. The bank's aggressive marketing of its services

included seminars explaining modern portfolio theory. Wells Fargo's early

success, particularly with indexing—weighting investments to match the

weightings of the Standard and Poor's 500—brought many new clients aboard.

Arbuckle retired as chairman at the end of 1977. Cooley

assumed the chairmanship in January 1978 with Reichardt succeeding him

as president.

Meanwhile, Wells Fargo secured a major legal victory that

would guarantee its long-term prosperity in its home market of California.

On May 16, 1978, after eight years of litigation in both federal and state

courts, the Supreme Court of California ruled in Wells Fargo's favor and

upheld the constitutionality of California's statutory nonjudicial foreclosure

procedure against a due process challenge. Thus, Wells Fargo could continue

to provide credit to borrowers at very affordable rates (nonjudicial foreclosure

is relatively swift and inexpensive). Associate Justice Wiley Manuel wrote

the opinion in Wells Fargo's favor for a unanimous court. The victory was

especially remarkable since during the tenure of Chief Justice Rose Bird

(1977-1987), the Court was notorious for its pro-plaintiff and anti-business

bias.

By the end of the 1970s, Wells Fargo's overall growth

had slowed somewhat. Earnings were only up 12% in 1979, compared with an

average of 19% between 1973 and 1978. In 1980 Cooley told Fortune, "It's

time to slow down. The last five years have created too great a strain

on our capital, liquidity, and people."

1980–1990

Recession of the early 1980s

In 1981, the banking community was shocked by the news

of a $21.3 million embezzlement scheme by a Wells Fargo employee, one of

the largest embezzlements ever. L. Ben Lewis, an operations officer at

Wells Fargo's Beverly Drive branch, pleaded guilty to the charges. Lewis

had routinely written phony debit and credit receipts to pad the accounts

of his cronies, and received a $300,000 cut in return.

The early 1980s saw a sharp decline in Wells Fargo's performance.

Cooley announced the bank's plan to scale down its operations overseas

and concentrate on the California market. In January 1983 Reichardt became

chairman and CEO of the holding company and of Wells Fargo Bank. Cooley,

who had led the bank since 1966, left to serve as chairman and CEO of Seafirst

Corporation. Reichardt relentlessly attacked costs, eliminating 100 branches

and cutting 3,000 jobs. He also closed down the bank's European offices

at a time when most banks were expanding their overseas networks. Paul

Hazen succeeded Reichardt as president in 1984.

Rather than taking advantage of banking deregulation,

which was enticing other banks into all sorts of new financial ventures,

Reichardt and Hazen kept things simple and focused on California. Reichardt

and Hazen beefed up Wells Fargo's retail network through improved services

such as an extensive automatic teller machine network, and through active

marketing of those services.

Purchase of Crocker National Corporation

In May 1986, Wells Fargo purchased rival Crocker National

Corporation from Britain's Midland Bank for about $1.1 billion. The acquisition

was touted as a brilliant maneuver by Wells Fargo. Not only did Wells Fargo

double its branch network in southern California and increase its consumer

loan portfolio by 85%, but the bank did it at an unheard of price, paying

about 127% of book value at a time when American banks were generally going

for 190%. In addition, Midland kept about $3.5 billion in loans of dubious

value.

Crocker doubled the strength of Wells Fargo's primary

market, making Wells Fargo the tenth largest bank in the United States.

Furthermore, the integration of Crocker's operations into Wells Fargo's

went considerably smoother than expected. In the 18 months after the acquisition,

5,700 jobs were trimmed from the banks' combined staff, 120 redundant branches

closed, and costs were cut considerably.

Before and after the acquisition, Reichardt and Hazen

aggressively cut costs and eliminated unprofitable portions of Wells Fargo's

business. During the three years before the acquisition, Wells Fargo sold

its realty-services subsidiary, its residential-mortgage service operation,

and its corporate trust and agency businesses. Over 70 domestic bank branches

and 15 foreign branches were also closed during this period. In 1987, Wells

Fargo set aside large reserves to cover potential losses on its Latin American

loans, most notably to Brazil and Mexico. This caused its net income to

drop sharply, but by mid-1989 the bank had sold or written off all of its

medium- and long-term Third World debt.

Concentrating on California was a very successful strategy

for Wells Fargo. But after its acquisition of Barclays Bank of California

in May 1988, few merger targets remained. One region Wells Fargo considered

expanding into in the late 1980s was Texas, where it made an unsuccessful

bid for Dallas's FirstRepublic Corporation in 1988. In early 1989 Wells

Fargo expanded into full-service brokerage and launched a joint venture

with the Japanese company Nikko Securities called Wells Fargo Nikko Investment

Advisors. Also in 1989, the company divested itself of its last international

offices, further tightening its focus on domestic commercial and consumer

banking activities.

On August 24, 1989, Wells Fargo obtained another important

legal victory from the California Court of Appeal for the First District.

In an opinion by Acting Presiding Justice William Newsom (father of politician

Gavin Newsom), the court held that Wells Fargo was not subject to tort

liability for breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing

just because it had taken a "hard line" approach in workout negotiations

with its borrowers and refused to modify or forbear enforcing the terms

of the relevant promissory notes. The borrowers had narrowly avoided foreclosure

only by liquidating a large amount of assets at fire sale prices to raise

cash and pay off their loans in full. By barring recovery against Wells

Fargo for the losses incurred by borrowers as a result of its hardball

tactics, the court enabled Wells Fargo to continue providing credit at

low interest rates, secure in the knowledge that it could aggressively

pursue defaulting borrowers without risking tort liability

1990–1995

Recession of the early 1990s

Wells Fargo & Company's major subsidiary, Wells Fargo

Bank, was still loaded with debt, including relatively risky real estate

loans, in the late 1980s. However, the bank had greatly improved its loan-loss

ratio since the early 1980s. Furthermore, Wells continued to improve its

health and to thrive during the early 1990s under the direction of Reichardt

and Hazen. Much of that growth was attributable to gains in the California

market. Indeed, despite an ailing regional economy during the early 1990s,

Wells Fargo posted healthy gains in that core market. Wells slashed its

labor force—by more than 500 workers in 1993 alone—and boosted cash flow

with technical innovations. The bank began selling stamps through its automated

teller machines (ATMs), for example, and in 1995 was partnering with CyberCash,

a software startup company, to begin offering its services over the Internet.

After dipping in 1991, Wells's net income surged to $283

million in 1992 before climbing briskly to $841 million in 1994. At the

end of 1994, after 12 years of service during which Wells Fargo & Co.

investors enjoyed a 1,781 percent return, Reichardt stepped aside as head

of the company. He was succeeded by Hazen. Wells Fargo Bank entered 1995

as the second largest bank in California and the seventh largest in the

United States, with $51 billion in assets. Under Hazen, the bank continued

to improve its loan portfolio, boost service offerings, and cut operating

costs. During 1995, Wells Fargo Nikko Investment Advisors was sold to Barclays

PLC for $440 million.

During 1995, Wells Fargo initiated discussions to merge

with American Express. This merger would have been notable, since both

companies were started originally by the same persons, Wells and Fargo.

It was thought that this merger could give Wells a more global presence.

However, egos clashed within the companies as to who would run the combined

firm. One issue centered around technology. Even though American Express

was going through a very expensive and ambitious technological upgrade,

it still would have lagged greatly behind Wells Fargo's systems, posing

tremendous integration risk. Also, there would have been regulatory issues,

especially since American Express owned an insurance company, Investors

Diversified Services (doing business as American Express Financial Advisors),

and this would have had to been divested. In the end it was decided not

to go through with the merger.

Takeover of First Interstate Bancorp

Late in 1995, Wells Fargo began pursuing a hostile takeover

of First Interstate Bancorp, a Los Angeles-based bank holding company with

$58 billion in assets and 1,133 offices in California and 12 other western

states. Wells Fargo had long been interested in acquiring First Interstate

and made a hostile bid for First Interstate in October 1995 initially valued

at $10.8 billion.

Other banks came forward as potential "white knights",

including Norwest, Bank One Corporation, and First Bank System. The latter

made a serious bid for First Interstate, with the two banks reaching a

formal merger agreement in November valued initially at $10.3 billion.

But First Bank ran into regulatory difficulties with the way it had structured

its offer and was forced to bow out of the takeover battle in mid-January

1996. Talks between Wells Fargo and First Interstate then led within days

to a merger agreement. When completed in April 1996, following an antitrust

review that stipulated the selling off of 61 bank branches in California,

the acquisition was valued at $11.3 billion. The newly enlarged Wells Fargo

had assets of about $116 billion, loans of $72 billion, and deposits of

$89 billion. It ranked as the ninth largest bank in the United States.

Wells Fargo aimed to generate $800 million in annual operational

savings out of the combined bank within 18 months, and immediately upon

completion of the takeover announced a workforce reduction of 16 percent,

or 7,200 positions, by the end of 1996. The merger, however, quickly turned

disastrous as efforts to consolidate operations, which were placed on an

ambitious timetable, led to major problems. Computer system glitches led

to lost customer deposits and bounced checks. Branch closures led to long

lines at the remaining branches. There was also a culture clash before

the two banks and their customers. Wells Fargo had been at the forefront

of high-tech banking, emphasizing ATMs and online banking, as well as the

small-staffed supermarket branches, at the expense of traditional branch

banking. By contrast, First Interstate had emphasized personalized relationship

banking, and its customers were used to dealing with tellers and bankers

not machines. This led to a mass exodus of First Interstate management

talent and to the alienation of numerous customers, many of whom took their

banking business elsewhere.

1995-to present

Merger with Norwest

The financial performance of Wells Fargo, as well as its

stock price, suffered from this botched merger, leaving the bank vulnerable

to being taken over itself as banking consolidation continued unabated.

This time, Wells Fargo entered into a friendly merger agreement with Norwest,

which was announced in June 1998. The deal was completed in November of

that year and was valued at $31.7 billion, with Wells Fargo merging into

Norwest. Norwest then changed its name to Wells Fargo & Company because

of the latter's greater public recognition and the former's regional connotations.

Norwest also relocated the headquarters of the new Wells Fargo to San Francisco

based on the bank's $54 billion in deposits in California versus $13 billion

in Minnesota. The head of Wells Fargo, Paul Hazen, was named chairman of

the new company, while the head of Norwest, Richard Kovacevich, became

president and CEO. The new Wells Fargo started off as the nation's seventh

largest bank with $196 billion in assets, $130 billion in deposits, and

15 million retail banking, finance, and mortgage customers. The banking

operation included more than 2,850 branches in 21 states from Ohio to California.

Norwest Mortgage had 824 offices in 50 states, while Norwest Financial

had nearly 1,350 offices in 47 states, ten provinces of Canada, the Caribbean,

Latin America, and elsewhere.

Integration

The integration of Norwest and Wells Fargo proceeded much

more smoothly than the combination of Wells Fargo and First Interstate.

A key reason was that the process was allowed to progress at a much slower

and more manageable pace than that of the earlier merger. The plan allowed

for two to three years to complete the integration, while the cost-cutting

goal was a more modest $650 million in annual savings within three years.

Rather than the mass layoffs that were typical of many mergers, Wells Fargo

announced a workforce reduction of only 4,000 to 5,000 employees over a

two-year period.

Already president and CEO, Kovacevich became chairman

as well when Hazen retired in May 2001. Another former Norwest executive,

John Stumpf, succeeded him as president in August 2005 and as CEO in June

2007; Kovacevich continues to serve as chairman today.

Later acquisitions

Continuing the Norwest tradition of making numerous smaller

acquisitions each year, Wells Fargo acquired 13 companies during 1999 with

total assets of $2.4 billion. The largest of these was the February purchase

of Brownsville, Texas-based Mercantile Financial Enterprises, Inc., which

had $779 million in assets. The acquisition pace picked up in 2000 with

Wells Fargo expanding its retail banking into two more states: Michigan,

through the buyout of Michigan Financial Corporation ($975 million in assets),

and Alaska, through the purchase of National Bancorp of Alaska Inc. ($3

billion in assets). Wells Fargo also acquired First Commerce Bancshares,

Inc. of Lincoln, Nebraska, which had $2.9 billion in assets, and a Seattle-based

regional brokerage firm, Ragen MacKenzie Group Incorporated. In October

2000 Wells Fargo made its largest deal since the Norwest-Wells Fargo merger

when it paid nearly $3 billion in stock for First Security Corporation,

a $23 billion bank holding company based in Salt Lake City, Utah, and operating

in seven western states. Wells Fargo thereby became the largest banking

franchise in terms of deposits in New Mexico, Nevada, Idaho, and Utah;

as well as the largest banking franchise in the West overall.

Following completion of the First Security acquisition,

Wells Fargo had total assets of $263 billion with some 140,000 employees.

It is the only bank in the United States to be rated AAA by Standard &

Poor's, and was named "The World's Safest US Bank" based on long-term foreign

currency ratings from Fitch Ratings and Standard & Poor's and long-term

bank deposit rankings from Moody's Investor Service for the year 2007.

Its strategy echoed that of the old Norwest: making selective

acquisitions and pursuing cross-selling of an ever-wider array of credit

and investment products to its vast customer base. Under Kovacevich's leadership,

Wells Fargo was posting smart growth in revenues and profits and was the

envy of the banking industry for the smooth way in which it had completed

the Norwest-Wells Fargo merger as well as its knack for integrating smaller

banks. There was speculation that the next 'stage' for Wells Fargo

might involve a major merger with an eastern bank that would create a nationwide

retail bank or a merger that would bring the bank one of the two other

things it did not have—a global presence and a large investment banking

arm, but Kovacevich seemed content with the concentration on western U.S.

banking and the broader finance and mortgage operations.

Acquisition of Wachovia

A former Wachovia branch converted to Wells Fargo in the fall of 2011

in Durham, North Carolina.

With the extraordinary circumstances of the financial panic of September

2008, however, Wells Fargo made a bid to purchase troubled Wachovia Corporation.

Although at first inclined to accept a September 29 agreement brokered

by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to sell its banking operations

to Citigroup for $2.2 billion, on October 3 Wachovia accepted Wells Fargo's

offer to buy all of the financial institution for $15.1 billion. Citigroup

on October 9 ended its effort to block the sale of Wachovia to Wells Fargo,

though it still threatened to sue both for $60 billion.

Acquisition of Wachovia would expand Wells Fargo's operations into nine

Eastern and Southern states. There would be big overlaps in operations

only in California and Texas, much less so in Nevada, Arizona, and Colorado.

Merger of Wells Fargo and Wachovia would create a superbank with $1.4 trillion

in assets and 48 million customers. The proposed merger was approved by

the Federal Reserve as a $12.2 billion all-stock transaction on October

12 in an unusual Sunday order. The acquisition was completed on January

1, 2009.

Such a smoothly fitting merger of Wachovia with a strong bank like Wells

Fargo was attractive, especially as it did not require government assistance.

Wells Fargo was more profitable than most of the 'megabanks' that had formed

in the 1990s, with the reason perhaps lying in its more modest ambitions.

|

Butterfield Overland Mail from Wikipedia

| The Butterfield Overland Mail Trail

was a stagecoach route in the United States, operating from 1857 to 1861.

It was a conduit for the passengers and U.S. mail from two eastern termini,

Memphis, Tennessee and St. Louis, Missouri, the routes from each eastern

terminal met at Fort Smith, Arkansas, and then continued through Indian

Territory, Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, ending in San Francisco, California.

On March 3, 1857, Congress under James Buchanan authorized the U.S. postmaster

general, Aaron Brown to contract for delivery of the U.S. mail from Saint

Louis, Missouri to San Francisco, California. Prior to this advent any

U.S. Mail bound for western localities was transported by ship across the

Gulf of Mexico to Panama, where it was freighted across the small country

to the Pacific and put back on a ship which then departed for points in

California.

Origins

Through the 1840s and 1850s there

was a desire for better communication between the east and west coasts

of the United States of America. Though there were several proposals for

railroads connecting the two coasts a more immediate realization was an

overland mail route across the west. Congress authorized the Postmaster

General to contract for mail service from Missouri to California as a means

of facilitating more settlement in the west overall. The Post Office Department

advertised for bids for an overland mail service on April 20, 1857. Bidders

were to propose routes from the Mississippi River westward.

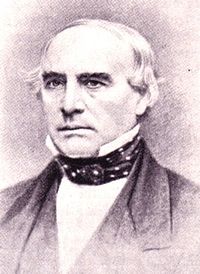

John Warren Butterfield

|

..

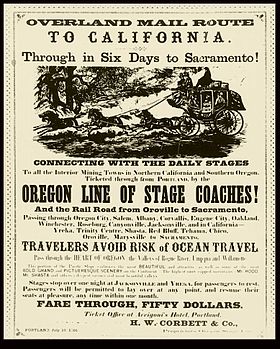

Overland Mail route advertising poster |

.. ..

John Warren Butterfield |

John W. Butterfield

and his associates William B. Dinsmore, William G. Fargo, James V. P. Gardner,

Marcus L. Kinyon, Alexander Holland, and Hamilton Spencer created a proposal

for a southern route beginning in St. Louis and heading west to California.

The Post Office Department received nine bids in all. The Postmaster-general,

Brown, was from Tennessee and favored a southern route. Although none of

the bidders had provided for the route, the Postmaster-general advocated

a southerly route, known as the Oxbow Route, with the idea that it could

remain in operation during the winter months.

"from St. Louis, Missouri, and from

Memphis Tennessee, converging at Little Rock, Arkansas; thence, via Preston,

Texas, or as nearly so as may be found advisable, to the best point of

crossing the Rio Grande, above El Paso and not far from Fort Fillmore;

thence along the new road being opened and constructed under direction

of the Secretary of the Interior, to Fort Yuma, California; thence, through

the best passes and along the best valleys for safe and expeditious staging,

to San Francisco."

This route was an extra 600 miles

(970 km) longer than the central and northern routes running through Denver,

Colorado and Salt Lake City, Utah, but was snow free. The bid and route

was awarded to Butterfield and his associates, for semi-weekly mail at

$600,000 per year. At that time it was the largest land-mail contract ever

awarded in the US. |

Butterfield Overland Mail Route

The stage routes from a Butterfield Overland Mail Company

map.

The contract with the U.S. Post Office, which went into

effect on September 16, 1858, identified the route and divided it into

eastern and western divisions. Franklin, Texas later to be named El Paso

was the dividing point and these two were subdivided into minor divisions,

five in the East and four in the West. These minor divisions were numbered

west to east from San Francisco, each under the direction of a superintendent.

San Francisco, each under the direction of a superintendent.

| Division |

Route |

Miles |

Hours |

| Division 1 |

San Francisco to Los Angeles |

282 |

72.20 |

| Division 2 |

Los Angeles to Fort Yuma |

462 |

80 |

| Division 3 |

Fort Yuma to Tucson |

280 |

71.45 |

| Division 4 |

Tucson to Franklin |

360 |

82 |

| Division 5 |

Franklin to Fort Chadbourne |

458 |

126.30 |

| Division 6 |

Fort Chadbourne to Colbert's Ferry |

282.5 |

65.25 |

| Division 7 |

Colbert's Ferry to Fort Smith |

192 |

38 |

| Division 8 |

Fort Smith to Tipton |

318.5 |

48.55 |

| Division 9 |

Tipton to St. Louis |

160 |

11.40 |

|

Totals |

2,795 |

596.35 |

|

|

Operation

| The Butterfield Overland Mail Company held the U.S. Mail

contract from September 15, 1857 on a six year contract. On that date stages

departed from St. Louis and San Francisco for the first time. The stage

from San Francisco arrived in St. Louis 23 days and 4 hours later with

the mail and six passengers. The scheduled time between the two points

was 25 days.

The Overland Mail made two trips a week over a period

of 2-1/2 years. Each Monday and Thursday morning the stagecoach would leave

Tipton and San Francisco on their cross continent, carrying passengers,

freight and up to 12,000 letters. The western fare one-way was $200, with

most stages arriving at their final destination 22 days later. The Butterfield

Overland Stage Company had more than 800 people in its employ, had 139

relay stations, 1800 head of stock and 250 Concord Stagecoaches in service

at one time.

During the 1860s there were few routes westward and the

Overland Stagecoach Route was one of the primary routes and had to be kept

open for settlers, miners and businessmen traveling west. Because the Overland

Stagecoach route was being harassed by bandits and Indians, Lincoln's War

Department responded by assigning a detachment from the 9th |

..

Overland mail commemorative stamp

issued by the U.S. Post Office,

100th Anniversary, October 10, 1958 |

Kansas Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel William O.

Collins from Fort Laramie in the Wyoming Territory. Collins' detachment

guarded the route between Independence, Missouri and Sacramento, California.

With the American Civil War looming, the competing Pony

Express was formed in 1860 to deliver mail faster and on a central/northern

route away from the volatile southern route. The Pony Express was to succeed

in delivering the mail in 10 days. But the Pony Express failed to win the

mail contract.

In March 1860, the Overland Stage Company was taken over

because of the debt owed to Wells Fargo and as a result John Butterfield

was forced out of the business. Butterfield's assets as well as those of

the Pony Express were to wind up with the Wells Fargo partners.

A correspondent for the New York Herald, Waterman Ormsby,

remarked after his 2,812-mile (4,525 km) trek through the western United

States to San Francisco on a Butterfield Stagecoach thus: "Had I not just

come out over the route, I would be perfectly willing to go back, but I

now know what Hell is like. I've just had 24 days of it." Ormsby was the

only passenger on the first East-West run of the Butterfield Stage who

journeyed the entire distance of the mail route. He sent periodic dispatches

to the paper describing his journey, including the pickup of passengers

outside the Lawrence Livery Stables.

Employing over 800 at its peak, it used 250 Concord Stagecoaches

and 1800 head of stock, horses and mules and 139 relay stations or frontier

forts in its heyday. The last Oxbow Route run was made March 21, 1861 at

the time of the outbreak of the Civil War. The Civil War started on April

12, 1861.

Route discontinued

An Act of Congress, approved March 2, 1861, discontinued

this route and service ceased June 30, 1861. On the same date the central

route from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Placerville, California, went into

effect. This new route was called the Central Overland California Route.

In March 1861, before the American Civil War had actually

begun at Fort Sumter, the United States Government formally revoked the

contract of the Butterfield Overland Stagecoach Company in anticipation

of the coming conflict.

Under the Confederate States of America, the Butterfield

route operated with limited success from 1861 until early 1862 using former

Butterfield employees.[citation needed] Wells Fargo continued its stagecoach

runs to mining camps in more northern locations until the coming of the

US Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. At least four battles of the American

Civil War and Apache Wars occurred at or near Butterfield mail posts, the

Battle of Stanwix Station, the Battle of Picacho Pass the Battle of Apache

Pass, and the Battle of Pea Ridge. Confederates attempted to keep the stations

from Tucson to Mesilla open while they destroyed the stations from Tucson

to Yuma which were used to supply the Union army as it advanced through

Traditional Arizona. The burning of the Stanwix Station and others led

to a significant delay to the Union advance, postponing the Fall of Tucson,

Arizona's western Confederate capital, which housed one of two territorial

courts; the other court was in Mesilla. All said engagements happened in

the Arizona and Arkansas sectors of the mail route.

Modern remnants

| There are surviving Stage stations at Oak Grove and the

most famous is near Warner Springs, California in San Diego County, California.

It and the property of Warner's Ranch 20 miles (32 km) away, where the

ranch house was used as a station, were declared to be National Historic

Landmarks in 1961. Warner's Ranch, was the Butterfield Station and a stop

for emigrant travelers to the West from 1849–1861, has two original adobe

buildings on the 221-acre (0.89 km2) property. The 1857 ranch house sometimes

housed travelers.

The Elkhorn Tavern in the Pea Ridge National Military

Park was another destination along the route that was rebuilt after the

Civil War. It is on one of the last sections of the trail that still exists-

Old Wire Road through Avoca, Rogers and Springdale, Arkansas. Also in Arkansas

is the town of Pottsville, which was built around Pott's Inn. Pott's Inn

was finished in 1859 and was a popular stop along the route. It survives

as a museum owned by the Pope County Historic Society.

When it was first established, the route proceeded due

east from Franklin, Texas, toward the Hueco Tanks; the remains of a stagecoach

stop are still visible at the Hueco Tanks State Historic Site.

The summit of Guadalupe Peak in Guadalupe Mountains National

Park features a stainless steel pyramid erected in 1958 to commemorate

the 100th anniversary of the Butterfield Overland Mail, which passed south

of the mountain.

Proposed Butterfield Overland Trail National Historic

Trail

On March 30, 2009, Barack Obama signed Congressional legislation

(Sec. 7209 of P.L. 111-11) to conduct a study of designating the trail

a National Historic Trail. The United States National Park Service is conducting

meetings in affected communities and doing Special Resource Study/Environmental

Assessment to determine whether it should become a trail and what the route

should be. |

..

Guadalupe Peak summit, with a

pyramid commemorating the 100th

anniversary of the

Butterfield Overland Mail. |

|