| Deadwood, South Dakota from Wikipedia

Deadwood is a city in South Dakota, United States, and

the county seat of Lawrence County. It is named for the dead trees found

in its gulch. The population was 1,270 according to a 2010 census. The

city includes the Deadwood Historic District, a National Historic Landmark

District, whose borders may be the city limits.

| History

19th century

The settlement of Deadwood began in the 1870s and has

been described as illegal, since it lay within the territory granted to

Native Americans in the 1868 Treaty of Laramie. The treaty had guaranteed

ownership of the Black Hills to the Lakota people, and disputes over the

Hills are ongoing, having reached the United States Supreme Court on several

occasions. However, in 1874, Colonel George Armstrong Custer led an expedition

into the Hills and announced the discovery of gold on French Creek near

present-day Custer, South Dakota. Custer's announcement triggered the Black

Hills Gold Rush and gave rise to the lawless town of Deadwood, which quickly

reached a population of around 5,000.

In early 1876, frontiersman Charlie Utter and his brother

Steve led a wagon train to Deadwood containing what were deemed to be needed

commodities to bolster business. The wagon train brought gamblers and prostitutes,

resulting in the establishment of profitable ventures. Demand for women

was high, and the business of prostitution proved to have a good market.

Madam Dora DuFran would eventually become the most profitable brothel owner

in Deadwood, closely followed by Madam Mollie Johnson. Businessman Tom

Miller opened the Bella Union Saloon in September of that year.

Another saloon was the Gem Variety Theater, opened April

7, 1877 by Al Swearengen who also controlled the opium trade in the town.

The saloon was destroyed by a fire and rebuilt in 1879. It burned down

again in 1899, causing Swearengen to leave the town.

The town attained notoriety for the murder of Wild Bill

Hickok, and Mount Moriah Cemetery remains the final resting place of Hickok

and Calamity Jane, as well as slightly less notable figures such as Seth

Bullock. It became known for its wild and almost lawless reputation, during

which time murder was common, and punishment for murders not always fair

and impartial. The prosecution of the murderer of Hickok, Jack McCall,

had to be sent to retrial because of a ruling that his first trial, which

resulted in an acquittal, was invalid because Deadwood was an illegal town.

This moved the trial to a Dakota Territory court, where he was found guilty

and then hanged.

As the economy changed from gold rush to steady mining,

Deadwood lost its rough and rowdy character and settled down into a prosperous

town. In 1876, a smallpox epidemic swept through the camp, with so many

falling sick that tents had to be set up to quarantine them. Also in that

year, General George Crook pursued the Sioux Indians from the Battle of

Little Big Horn on an expedition that ended in Deadwood, and that came

to be known as the Horsemeat March. The Homestake Mine in nearby Lead was

established in 1877.

A fire on September 26, 1879 devastated the town, destroying

over 300 buildings and consuming everything belonging to many inhabitants.

Many of the newly impoverished left town to try their luck elsewhere, without

the opportunities of rich untapped veins of ore that characterized the

town's early days.

A narrow-gauge railroad, the Deadwood Central Railroad,

was founded by Deadwood resident J.K.P. Miller and his associates in 1888,

in order to serve their mining interests in the Black Hills. The railroad

was purchased by the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad in 1893. A

portion of the railroad between Deadwood and Lead was electrified in 1902

for operation as an interurban passenger system, which operated until 1924.

The railroad was abandoned in 1930, apart from a portion from Kirk to Fantail

Junction, which was converted to standard gauge. The remaining section

was abandoned by the successor Burlington Northern Railroad in 1984.

Some of the other early town residents and frequent visitors

included Al Swearengen, E. B. Farnum, Charlie Utter, Sol Star, Martha Bullock,

A. W. Merrick, Samuel Fields, Calamity Jane, Dr. Valentine McGillycuddy,

the Reverend Henry Weston Smith, and Wild Bill Hickok.

20th and 21st centuries

Another major fire in September 1959 came close to destroying

the town. About 4,500 square miles (12,000 km2) were burned and an evacuation

order was issued. Nearly 3,600 volunteer and professional firefighters,

including personnel from the Homestake Mine and Ellsworth Air Force Base,

worked to contain the fire, which resulted in a major regional economic

downturn. |

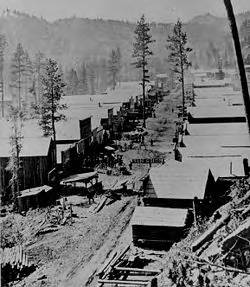

A photograph of Deadwood in 1876. General

view of the Dakota Territory gold rush

town from a hillside above.

.

The Gem in 1878

.

Possible location of the original

Nuttal & Mann's saloon where

Wild Bill Hickok was killed,

624 Main Street, Deadwood |

The entire town was designated a National Historic Landmark

in 1961. However, the town underwent additional decline and financial stresses

during the next two decades. Interstate 90 bypassed it in 1964 and its

brothels were shut down after a 1980 raid. A fire in December 1987 destroyed

the historic Syndicate Building and a neighboring structure. The fire spurred

the "Deadwood Experiment", in which gambling was tested as a means of revitalizing

a city center. At the time, gambling was legal only in the state of Nevada

and in Atlantic City. Deadwood was the first small community in the U.S.

to seek legal gambling revenues as a way of maintaining local historic

qualities. Gambling was legalized in Deadwood in 1989 and immediately brought

significant new revenues and development. The pressure of development may

have an effect on the historical integrity of the landmark district.

Chinatown

The gold rush attracted Chinese immigrants to the area.

Their population peaked at 250. A few engaged in mining; most worked in

service enterprises. A quarter arose on Main Street, encouraged by the

lack of restrictions on foreign property ownership in Dakota Territory

and a relatively high level of tolerance. The quarter's residents also

included African-Americans and Americans of European extraction. The state

sponsored an archeological dig in the area during the 2000s.

|

Dora DuFran from Wikipedia

| Madam Dora DuFran or Dora Bolshaw (née Amy Helen

Dorothea Bolshaw) (November 16, 1868 - August 5, 1934) was one of the leading

and most successful madams in the Old West days of Deadwood, South Dakota.

Biography

Dora was born in Liverpool, England. She emigrated to

the United States with her parents Joseph John (Nov. 14, 1842 - March 26,

1911) and Isabella Neal Cummings Bolshaw (Nov. 12, 1844 - April 12, 1911)

sometime around 1869. The family settled first at Bloomfield, New Jersey,

then moved to Lincoln, Nebraska in 1876 or 1877. An extremely good looking

woman in her youth, Dora became involved in prostitution around the age

of 13 or 14. She then became a dance hall girl, calling herself Amy Helen

Bolshaw. By the time the gold rush hit Deadwood when she was 15, Dora promoted

herself to Madam and began operating a brothel.

Dora coined the term "cathouse."

Career

Although she preferred having pretty girls work in her

brothel, the selection in that part of the west was extremely limited.

She usually did, however, demand that her girls practice good hygiene and

dress well. She picked up several girls who arrived in Deadwood via the

wagon train led by Charlie Utter. From time to time Old West personality

Martha Jane Burke (Calamity Jane, 1852–1903) was in her employ. Her main

competition in Deadwood was Madam Mollie Johnson. Dora coined the term

"cathouse" after having Charlie Utter bring her a wagon of cats for her

Deadwood brothel.

|

Dora DuFran was one of Deadwood's

most successful madams |

She had several brothels over the years. The most popular

was called "Diddlin' Dora's," located on Fifth Avenue in Belle Fourche,

South Dakota. Her other brothels in South Dakota were located in Lead,

Miles City, Sturgis, South Dakota, and Deadwood. Although she married a

man named Joseph M. DuFran (1862 - August 3, 1909), Dora continued her

brothel operations throughout the marriage. She eventually moved her operations

to Rapid City, South Dakota, where she continued having success as a brothel

owner. Dora died of heart failure in 1934. Her pet parrot Fred and husband

Joseph are buried with her at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood.

Publication

DuFran (under the pseudonym: d'Dee) published a 12-page

booklet on Calamity Jane titled Low Down on Calamity Jane (Rapid City,

South Dakota: 1932). This booklet was later reprinted in an expanded 47-page

version, edited by Helen Rezatto (Deadwood, South Dakota: 1981).

Dora DuFran was played by Melanie Griffith in the 1995

made-for-tv movie 'Buffalo Girls', based on the book by Larry McMurtry.

|

| Mollie Johnson from Wikipedia

Deadwood Madam Mollie Johnson was a 19th Century madam.

Johnson was born in Alabama, and migrated west due to the demand for working

prostitutes. Indications are that she began working that trade in her early

teens, around the age of 15 or 16 by some reports. However, definite information

on her early life is unconfirmed.

She was known in Deadwood, South Dakota as the "Queen

of the Blondes". Her nickname came from the fact that she had three blonde

protégés who worked for her who also maintained their own

boarding houses. The twenty-ish foursome, Mollie Johnson and her girls

Ida Clark, Ida Cheplan and Jennie Duchesneau, were often embroiled in personal

and physical altercations among each other.

She first appeared in Deadwood shortly after the gold

rush, and was first mentioned in public writing in February, 1878, when

she married Lew Spencer, an African American comedian who was performing

at the time in the Bella Union Theater. Although married, Johnson continued

to work in her chosen profession, both as prostitute and madam. Spencer

eventually left Deadwood and was later arrested in Denver, Colorado for

shooting his other wife. Evidently Spencer had been married to both a woman

in Denver, and Johnson. There are no indications that Johnson and Spencer

ever saw one another afterward.

Reportedly a widow before her arrival in Deadwood, and

in her early to mid-20's, Johnson was described as being a pretty woman,

and a very good businesswoman. The competition for brothel owners in Deadwood

was light, as there were very few girls to choose from, but plenty of men.

Her main opposition during most of her time in Deadwood was Madam Dora

DuFran, but there is no indication that the two madams didn't get along.

The brothel houses were described in the papers as being

a resort for naughty men. Mollie Johnson was also noted to be of a kind

heart, caring for the dead body of one of her girls, before trying to save

her possessions in the "Big Deadwood Fire" of September 26, 1879. She immediately

opened another brothel, and suffered two more fires over the course of

the years. She reportedly left Deadwood, as business dropped off, in January,

1883. As to where she went or what happened to her following her departure

of Deadwood is unknown.

|

| Wild Bill Hickok – Davis Tutt shootout from Wikipedia

The Wild Bill Hickok–Davis Tutt shootout was a gunfight

that occurred on July 21, 1865 in the town square of Springfield, Missouri

between Wild Bill Hickok, and a local cowboy named Davis Tutt. It is considered

to be one of the few recorded instances in the Wild West of a one-on-one

pistol quickdraw duel in a public place, in the manner later made iconic

by countless dime novels, radio operas, and Western films such as Gary

Cooper in High Noon and Clint Eastwood in the Dollars Trilogy. The first

story of the shootout was detailed in an article in Harper's in 1867, instantly

making Hickok a household name.

Prelude

Tutt and Hickok were both dedicated gamblers who frequented

the same saloons and had at one point been friends, despite the fact that

Tutt was a Confederate Army veteran, while Hickok had been a scout for

the Union. Little is known about Davis Tutt's background. He originally

came from Marion County, Arkansas, where his family had been involved in

the Tutt-Everett War, during which several of his family members had been

killed. He went west following the Civil War.

The eventual falling out between Hickok and Tutt reportedly

occurred following grudges over women; while sources differ, there were

rumors that Hickok had once dallied with Tutt's sister, possibly fathering

an illegitimate child. Tutt had also been observed paying a great deal

of attention to Wild Bill's then paramour, Susanna Moore.

By all accounts, by July 20, 1865, the two men were sworn

enemies. Hickok staunchly refused to play in any card game that included

Tutt. Tutt retaliated by openly supporting other local card-players with

advice and money in a dedicated attempt to bankrupt Hickok.

The card game

The simmering conflict eventually came to a head during

a game of poker at the Lyon House Hotel (now called the Old Southern Hotel).

Wild Bill was playing against several other local gamblers while Tutt stood

nearby, loaning money as needed and "encouraging [them], coaching [them]

on how to beat Hickok."

The game was being played for high stakes, and Hickok

did well, winning about $200 ($3,080 in 2010 dollars) of what was essentially

Tutt's money. Irritated by his losses and unwilling to admit defeat, Tutt

suddenly reminded Hickok of a $40 debt from a horse trade. Hickok shrugged

and paid the sum, but Tutt was unappeased. He then claimed that Hickok

owed him an additional $35 from a past poker game, back when Hickok was

still willing to play against Tutt. "I think you are wrong, Dave," said

Hickok. "It's only twenty-five dollars. I have a memorandum in my pocket."

Tutt grabbed one of Hickok's most prized possessions off

the table, his Waltham Repeater gold pocket watch, and crowed, "Fine, I'll

just keep your watch 'til you pay me that thirty-five dollars!" Hickok

was shocked and livid, but since all the other players were Tutt's allies,

and the room was crowded; his hands were tied. Humiliated and stone-faced

with anger, he quietly warned Tutt not to wear the watch in public. Tutt

sneered back, "I intend on wearing it first thing in the morning!"

This was the breaking point for Hickok's patience. "If

you do, I'll shoot you," Bill replied bluntly and calmly. "I'm warning

you here and now not to come across that town square with it on." Hickok

then immediately pocketed the rest of his winnings and left without further

incident or conversation. The stage was set for the next day's events.

The gunfight

Though Tutt had humiliated his rival, Hickok's ultimatum

essentially forced his hand. To go back on his very public boast would

make everyone think he was afraid of Hickok, and so long as he intended

to stay in Springfield, he could not afford to show cowardice. The next

day, he arrived at the town square around 10 a.m. with Hickok's watch openly

hanging from his waist pocket. The word quickly spread that Tutt was making

good on his pledge to humiliate Hickok, and reached Hickok's own ears within

an hour.

According to the testimony of Eli Armstrong and supported

by two other witnesses, John Orr and Oliver Scott, Hickok met Tutt at the

square and, along with Armstrong and Orr, they sat to discuss the terms

of the watch's return. Tutt now wanted $45, Armstrong tried to convince

Tutt to accept the original $35 and negotiate for the rest later, but Hickok

was still adamant that he only owed $25. Tutt then held the watch in front

of Hickok and stated he would accept no less than $45. Both then said they

didn't want to fight and they all went for a drink together. Tutt later

left, went to the livery stable and then returned to the square.

At a few minutes before 6 p.m., Hickok was seen calmly

approaching the square from the south, his Colt Navy in hand. His armed

presence caused the crowd to immediately scatter to the safety of nearby

buildings, leaving Tutt alone in the northwestern corner of the square.

At a distance of about 75 yards (70 meters), Hickok stopped, facing Tutt,

and called out, "Dave, here I am." He cocked his pistol, holstered it on

his hip, and gave a final warning, "Don't you come across here with that

watch." Tutt did not reply, but stood with his hand on his pistol.

Davis Tutt was acknowledged as the better marksman, but

both showed courage by all accounts. Both men faced each other sideways

in the dueling position and hesitated briefly. Then Tutt reached for his

pistol. Hickok drew his gun and steadied it on his opposite forearm. The

two men fired a single shot each at essentially the same time, according

to the reports. Tutt missed, but Hickok's bullet struck Tutt in the left

side between the fifth and seventh ribs. Tutt called out, "Boys, I'm killed,"

ran onto the porch of the local courthouse and back to the street, where

he collapsed and died.

Trial and aftermath

The next day, a warrant was issued for Hickok's arrest

and two days later he was arrested. Bail was initially denied, as was common

in murder cases of the time. Hickok eventually posted a bail of $2,000

(2010:$30,800) on the same day, after the magistrate reduced the charge

from murder to manslaughter based on the circumstances. Hickok was arrested

under the name of William Haycocke (the name Hickok had been using in Springfield)

for the manslaughter of David Tutt. During the trial, the names were amended

to J. B. Hickok and Davis Tutt/Little Dave, "little" being the equivalent

in that period for the present day "Junior" to indicate having the same

name as the father.

Hickok's manslaughter trial began on August 3, 1865 and

lasted three days. Twenty-two witnesses from the square testified at the

trial. Hickok's lawyer was the prestigious Colonel John S. Phelps, former

wartime governor of Arkansas. The prosecution was led by Major Robert W.

Fyan, and the judge was Sempronius Boyd. The trial transcripts have been

lost, but newspaper reports of the trial indicate that Hickok, as expected,

claimed self-defense. The most disputed fact at the trial was who fired

first. Only four witnesses actually watched the fight. Two claimed both

men fired, but they could not tell who drew first. One said he was standing

behind Hickok so he only saw Hickok draw, as his view of Tutt was blocked.

Another said Tutt did not fire, but admitted noticing Tutt's gun had a

discharged chamber. The other witnesses all stated that while they did

not see the shooting, they heard only one shot.

Despite Hickok's claim of self-defense being technically

illegitimate under the state law pertaining to mutual combat (since he

had come to the square armed and in expectation of a fight), the jury decided

that he was still justified in shooting Tutt; the unwritten sensibilities

of the time dictated that, as Tutt was both the initiator of the fight

and the first to display overt aggression, and two witness reports indicated

that Tutt was the first to reach for his pistol, Hickok was absolved of

guilt for shooting him down. It was also noted that Hickok was seen as

particularly honorable for giving Tutt several chances to avoid the conflict

instead of simply shooting him the moment he felt he was being shown disrespect.

Judge Sempronius Boyd gave the jury two apparently contradictory instructions.

He first instructed the jury that a conviction was its only option under

the law. He then instructed them that they could apply the unwritten law

of the "fair fight" and acquit, an action known as jury nullification which

allows a jury to make a finding contrary to the law. The trial ended with

an acquittal on August 6, 1865, after the jury deliberated for only "an

hour or two" before reaching a verdict of not guilty, a verdict that was

not popular at the time. The verdict was both expected and well in keeping

with the "trail law" of the day; as stated by a modern historian, "Nothing

better described the times than the fact that dangling a watch held as

security for a poker debt was widely regarded as a justifiable provocation

for resorting to firearms."

Due to its notoriety, the gunfight has since received

much research attention, with many writing that Hickok killed Tutt for

no reason whatsoever, short of humiliation. Many have argued that while

Hickok felt humiliated by Tutt wearing the watch, Tutt could also claim

the same humiliation if he failed to wear the watch, essentially bowing

to Hickok's warning. Several weeks after the gunfight, on September 13,

1865, Colonel George Ward Nichols, a writer for Harper's, sought out Hickok

and began the interviews that would eventually turn the then-unknown gunfighter

into one of the great legends of the Old West. Davis Tutt's body was buried

in the Springfield City Cemetery and in March 1883 it was disinterred by

Lewis Tutt, a former slave of the Tutt family, and reburied in Maple Park

Cemetery.

|

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|