Dime Novel from Wikipedia

| Dime novel, though it has a specific meaning, has also

become a catch-all term for several different (but related) forms of late

19th-century and early 20th-century U.S. popular fiction, including “true”

dime novels, story papers, five- and ten-cent weekly libraries, “thick

book” reprints, and sometimes even early pulp magazines. The term was being

used as late as 1940, in the short-lived pulp Western Dime Novels. Dime

novels are, at least in spirit, the antecedent of today's mass market paperbacks,

comic books, and even television shows and movies based on the dime novel

genres. In the modern age, "dime novel" has become a term to describe any

quickly written, lurid potboiler and as such is generally used as a pejorative

to describe a sensationalized yet superficial piece of written work...

History

Origin of term

It is generally agreed that the term originated with the

first book in Beadle & Adam's Beadle's Dime Novel series, Maleaska,

the Indian Wife of the White Hunter, by Ann S. Stephens, dated June 9,

1860. The novel was essentially a reprint of Stephens's earlier serial

that appeared in the Ladies' Companion magazine in February, March, and

April 1839. The dime novels varied in size, even within this first Beadle

series, but were roughly 6.5 by 4.25 inches (17 by 10.8 cm), with 100 pages.

The first 28 were published without a cover illustration, in a salmon colored

paper wrapper, but a woodblock print was added with issue 29, and reprints

of the first 28 had an illustration added to the cover. Of course, the

books were priced at ten cents.

This series ran for 321 issues, and established almost

all the conventions of the genre, from the lurid and outlandish story to

the melodramatic double titling that was used right up to the very end

in the 1920s. Most of the stories were frontier tales reprinted from the

vast backlog of serials in the story papers and other sources,] as well

as many originals. |

An example of the original dime novel

series, circa 1860. |

As the popularity of dime novels increased, original stories

came to be the norm. The books were themselves reprinted many times, sometimes

with different covers, and the stories were often further reprinted in

different series, and by different publishers.

Beadle's Dime Novels were immediately popular among young,

working-class audiences, owing to an increased literacy rate around the

time of the American Civil War. By the war's end, there were numerous competitors

like George Munro and Robert DeWitt crowding the field, distinguishing

their product only by title and the color choice of the paper wrappers.

Even Beadle & Adams had their own alternate "brands", such as the Frank

Starr line. As a whole, the quality of the fiction was derided by higher

brow critics and the term 'dime novel' quickly came to represent any form

of cheap, sensational fiction, rather than the specific format.

Prices

Adding to the general confusion as to what is or is not

a dime novel, many of the series, though similar in design and subject

matter, cost ten to fifteen cents. Even Beadle & Adams complicated

the issue with a confusing array of titles in the same salmon colored covers

at different price points. Also, there were a number of ten-cent, paper

covered books of the period that featured medieval romance stories and

soap opera-ish tales. This made it hard to define what falls within the

definition of a true dime novel, with the division depending on format,

price, or style of material for the classification. Examples of Dime Novel

series that showcase the diversity of the term include: Bunce's Ten Cent

Novels, Brady's Mercury Stories, Beadle's Dime Novels, Irwin P. Beadle's

Ten Cent Stories, Munro's Ten Cent Novels, Dawley's Ten Penny Novels, Fireside

Series, Chaney's Union Novels, DeWitt's Ten Cent Romances, Champion Novels,

Frank Starr's American Novels, Ten Cent Novelettes, Richmond's Sensation

Novels, Ten Cent Irish Novels, etc.

| In 1874, Beadle & Adams by added the novelty of color

to the covers when their New Dime Novels series replaced the flagship title.

The New Dime Novels were issued with a dual numbering system on the cover,

one continuing the numbering from the first series, and the second and

more prominent one indicating the number within the current series, i.e.,

the first issue was numbered 1 (322). The stories were largely reprints

from the first series. Like its predecessor, Beadle's New Dime Novels ran

for 321 issues, until 1885.

Development of the dime novel

As noted, much of the material for the dime novels came

from the storypapers, which were weekly, eight page newspaper-like publications,

varying in size from tabloid to a full fledged newspaper format, and usually

costing five or six cents. They started in the mid 1850s and were immensely

popular, some titles running for over fifty years on a weekly schedule.

They are perhaps best described as the television of their day, containing

a variety of serial stories and articles, with something aimed at each

members of the family, and often illustrated profusely with woodcut illustrations.

Popular storypapers included The Saturday Journal, Young Men of America,

Golden Weekly, Golden Hours, Good News, Happy Days.

Although the larger part of the stories stood alone, in

the late 1880s series characters began to appear and quickly grew in popularity.

The original Frank Reade stories first appeared in Boys of New York. Old

Sleuth, appearing in The Fireside Companion story paper beginning in 1872,

was the first dime novel detective and began the trend away from the western

and frontier stories that dominated the story papers and dime novels up

to that time. He was the first character to use the word “sleuth” to denote

a detective, the word's original definition being that of a bloodhound

trained to track. And he also is responsible for the popularity of the

use of the word “old” in the names of competing dime novel detectives,

such as Old Cap Collier,

|

..

The New Dime Novel Series

introduced color covers, but

reprinted stories from the original

series. |

Old Broadbrim, Old King Brady, Old Lightning, Old Ferret

and many, many others. Nick Carter first appeared in 1886 in The New York

Weekly. All three characters would graduate to their own ten-cent weekly

titles within a few years.

Old Sleuth Library, 1888 |

Frank Tousey's major black and white library, 1884 |

Changing formats

In 1873, the house of Beadle & Adams had introduced

a new ten-cent format, 9 by 13.25 inches (230 × 337 mm), with only

32 pages and a black and white illustrated cover, with the title New and

Old Friends. It was not a success, but the format was so much cheaper to

produce that they tried again in 1877 with The Fireside Library and Frank

Starr's New York Library. The first reprinted English love stories, the

second contained hardier material but both titles caught on. Publishers

were no less eager to follow a new trend then than now. Soon the newsstands

were flooded by ten-cent weekly “libraries”. These publications also varied

in size, from as small as 7 x 10 inches (The Boy's Star Library is an example)

to 8.5 x 12 (New York Detective Library). The Old Cap Collier Library was

issued in both sizes, plus a booklet form. Each issue tended to feature

a single story, as opposed to the story papers, and many of them were devoted

to single characters. Frontier stories, evolving into westerns, were still

popular, but the new vogue tended to urban crime stories. One of the most

successful titles, Frank Tousey's New York Detective Library eventually

came to alternate stories of the James Gang with stories of Old King Brady,

detective, and in a rare occurrence in the dime novel world, there were

several stories which featured them both, with Old King Brady doggedly

on the trail of the vicious gang.

The competition was fierce, and publishers were always

looking for an edge. Once again, color came into the fray when Frank Tousey

introduced a weekly with brightly color covers in 1896. Street & Smith

countered by issuing a smaller format weekly with muted colors Such titles

as New Nick Carter Weekly (continuing the original black and white Nick

Carter Library), Tip-Top Weekly (introducing Frank Merriwell) and others

were 7 x 10 with thirty-two pages of story, but the 8.5 x 11 Tousey format

carried the day and Street & Smith, soon followed suit. The price was

also dropped to five cents, making the magazines more accessible to children.

This would be the last major permutation of the product before it evolved

into pulp magazines. Ironically, for many years it has been the nickel

weeklies that most people refer to when using the term "dime novel."

.. ..

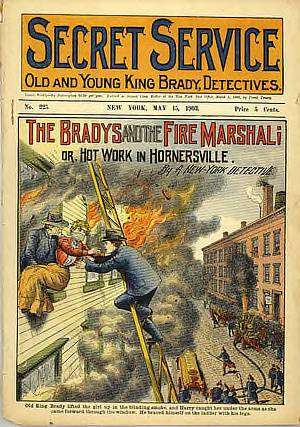

One of the most popular color covered nickel weeklies,

Secret Service, no. 225, May 15, 1903.

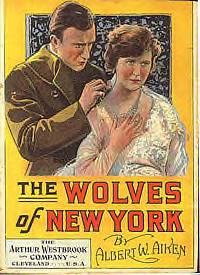

An example of the "thick book" series,

American Detective Series no. 21,

from the Arthur Westbrook Co..

|

The nickel weeklies proved very popular, and their numbers

grew quickly. Frank Tousey and Street & Smith dominated the field.

Tousey had his “big six” : Work and Win (featuring Fred Fearnot, a serious

rival to the soon to be popular Frank Merriwell) Secret Service, Pluck

and Luck, Wild West Weekly, Fame and Fortune, and The Liberty Boys of ’76,

all of which ran over a thousand weekly issues apiece. 7] Street &

Smith had New Nick Carter Weekly, Tip Top Weekly, Buffalo Bill Stories,

Jesse James Stories, Brave & Bold Weekly and many others. The Tousey

stories were on the whole the more lurid and sensational of the two.

Perhaps the most confusing of all the various formats

that are lumped together under the term dime novel are the so-called “thick-book”

series, largely published by Street & Smith, J. S. Ogilvie and Arthur

Westbrook. These books were published in series, ran roughly 150-200 pages,

and were 4.75 by 7 inches (121 × 180 mm), often with color covers

on a higher grade stock. They reprinted multiple stories from the five-

and ten-cent weeklies, often slightly rewritten to tie the material together.

All dime novel publishers were canny about repurposing

material. but Street & Smith made it more of an art form. They developed

the practice of publishing four consecutive, related tales of, for example,

Nick Carter, in the weekly magazine, then combining the four stories into

one edition of the related thick book series, in this instance, the New

Magnet Library. The Frank Merriwell stories appeared in the Medal, New

Medal and Merriwell Libraries, Buffalo Bill in the Buffalo Bill Library

and Far West Library, and so on. What confuses many dealers and new collectors

today is that though the thick books were still in print as late as the

1930s, they carry the original copyright date of the story, often as early

as the late nineteenth century, leading some to assume they have original

dime novels when the books are only distantly related.

End of the dime novel

In 1896, Frank Munsey had converted his juvenile magazine,

The Argosy into a fiction magazine for adults and the first pulp. By the

turn of the century, new high-speed printing techniques combined with the

cheaper pulp paper allowed him to drop the price from twenty five cents

to ten cents, and the magazine really took off. In 1910 Street and Smith

converted two of their nickel weeklies, New Tip Top Weekly and Top Notch

Magazine, into pulps; in 1915, Nick Carter Stories, itself a replacement

for the New Nick Carter Weekly, morphed into Detective Story Magazine,

and in 1919, New Buffalo Bill Weekly became Western Story Magazine. Harry

Wolff, the successor in interest to the Frank Tousey titles, continued

to reprint many of them up into the mid 1920s, most notably Secret Service,

Pluck and Luck, Fame and Fortune, and Wild West Weekly. The latter two

were purchased by Street & Smith in 1926 and converted into pulp magazines

the following year. That effectively ended the reign of the dime novel.

Collections

In the late 1940s to the early 1950s, collecting dime

novels became very popular, and prices soared. Albert Johannsen authored

an enormous two volume scholarly work, The House of Beadle & Adams,

which is exhaustive in its detail. Even at that time the cheap publications

were crumbling into dust and becoming hard to find. William J. Benners

was another of the early historians of the dime novel. He was also a publisher

and author. Edward T. LeBlanc, a longtime editor of the periodical Dime |

Novel Round-Up, was also an avid collector and bibliographer

of the format. T wo of the prominent collectors, Charles Bragin and Ralph

Cummings, issued a number of reprints of particularly hard to find titles

from some of the weekly libraries. But most of the collectors were men

who remembered the stories from childhood, and as they passed on, the craze

subsided and dime novels, of all varieties, lost their appeal and are only

marginally collected today. |

| Ned Buntline from Wikipedia

Ned Buntline (March 20, c. 1813 – July 16, 1886), was

a pseudonym of Edward Zane Carroll Judson (E. Z. C. Judson), an American

publisher, journalist, writer and publicist best known for his dime novels

and the Colt Buntline Special he is alleged to have commissioned from Colt's

Manufacturing Company.

Naval and military experience

Edward Judson was born in Stamford, Delaware County, New

York. As a boy, Ned ran away to sea as a cabin-boy, and the next year shipped

on board of a man-of-war. When he was thirteen years old, he rescued the

crew of a boat that had been run down by a Fulton ferry boat, and received

a commission as midshipman in the U.S. Navy from President Van Buren. On

being assigned to the “Levant,” he challenged 13 midshipmen to duels who

refused to mess with him because he had been a common sailor, and fought

the seven who accepted, wounding four, while escaping without a wound himself.

"Buntline" is a nautical term for a rope at the bottom

of a square sail. As a seaman, he fought in the Seminole Wars, though he

saw little combat. After four years at sea, he resigned. During the Civil

War, he served as an enlisted man in the 1st New York Mounted Rifles, although

he later claimed to have been chief of scouts among the Indians, with the

rank of colonel, and to have received twenty wounds.

Early literary efforts

His first literary efforts began with a story of adventure

in the Knickerbocker in 1838. Buntline spent several years in the east

starting up newspapers and story papers, only to have most of them fail.

An early success that helped launch his fame was a gritty serial story

of the Bowery and slums of New York City titled The Mysteries and Miseries

of New York. An opinionated man, he strongly advocated nativism and temperance.

Involvement in riots

He became editor of a weekly story paper, called Ned Buntline's

Own, in 1848. Through his writing in its columns and his association with

New York City's notorious gangs of the early 19th century, he was one of

the instigators of the Astor Place Riot which left 23 people dead. In September

1849, he was sentenced to a $250 fine and a year's imprisonment. After

his release he devoted himself to writing sensational stories for weekly

newspapers, and his income from this source is said to have amounted to

$20,000 a year. He was also involved in a nativist riot in St. Louis, which

would later come back to haunt him. |

.. . .

Ned Buntline

.

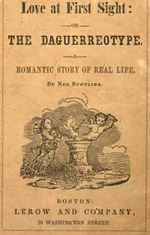

Love at First Sight: or the Daguerreotype,

a Romantic Story of Real Life by Ned Buntline

(Lerow & Co., Washington St., Boston, ca.1847) |

..........

......Ned Buntline, Bufalo

Bill Cody, Giuseppina Morlacchi, Texas Jack Omohundro, 19th c.

Temperance and politics

Although a heavy drinker, he traveled around the country

giving lectures about temperance, and until the presidential canvass of

1884 was an ardent Republican politician. It was on one of his temperance

lecture tours that he encountered Buffalo Bill.

Wild Bill Hickok

While traveling through Nebraska, Buntline heard that

Wild Bill Hickok was in Fort McPherson. Having read a popular article about

the Wild West figure, Buntline hoped to interview Hickok with the desire

to write a dime novel about him. Finding Hickok in a saloon, he rushed

up to him saying "There's my man! I want you!". By this time in his life,

Hickok had an aversion to surprises. He threatened Buntline with a gun

and ordered him out of town in twenty-four hours. Buntline took him at

his word and left the saloon. Still looking to get information on his subject,

Buntline took to finding Hickock's friends. It is likely that this is how

he first met "Buffalo Bill," whose real name was William Cody.

Buffalo Bill

Traveling with Cody on an Indian scout, Buntline became

enamored with the gregarious man. He gave up his desire to write a novel

about Hickok and he decided to write one on Cody instead. Cody at first

was a reluctant hero. Buntline's dime novel series: Buffalo Bill Cody -

King of the Border Men was a fantastic success. Buntline immediately began

cajoling Cody to come east and take part in a stage play. Cody at first

resisted, but after an eastern trip financed by wealthy newspapermen, decided

he enjoyed the spotlight after all. Buntline wrote a play titled Scouts

of the Prairie, which opened in Chicago in December 1872 and starred Cody

and Texas Jack Omohundro. Although panned by critics, the play was a great

success, and it was performed to packed theaters across the country.

While successful, Cody found he could not keep the money

he made, nor stand the eccentricities of Buntline. At the height of its

popularity, the show closed in June 1873, and Cody and Buntline went their

separate ways.

Later work

Buntline continued to write dime novels, though none was

as successful as his earlier work. He settled into his home in Stamford,

New York, where he died of congestive heart failure in 1886. Although he

was once one of the wealthiest authors in America, his wife had to sell

his beloved home "The Eagle's Nest" to pay the bills.

. |

Giuseppina Morlacchi from Wikipedia

.

| Giuseppina Morlacchi (1846 - July 25, 1886) was an Italian

American ballerina and dancer, who introduced the can-can to the American

stage, and married the scout and actor Texas Jack Omohundro. She was born

in Milan, and attended dance school at La Scala. She debuted on the stage

in 1856 at Genoa. In short time she became a well-known dancer, touring

the continent and England. In Lisbon, she met noted artist and manager

John DePol, who persuaded her to go to America.

In October 1867, she made her American debut at Banvard's

Museum in New York City, performing The Devil's Auction. She became an

immense success, and DePol took the show to Boston. During her rise to

fame DePol insured her legs for $100,000 after which newspapers claimed

Moriacchi was 'more valuable than Kentucky'.

From 1867 though 1872 Giuseppina traveled the United States

dancing in various venues with Morlacchi Ballet Troupe which she formed

performing before various politicians, dignitaries and the Grand Duke of

Russia. On January 6, 1868, the company played at the Theatre Comique and

premiered a new type of dance, billed as "...Grand Gallop Can-Can, composed

and danced by Mlles. Morlacchi, Blasina, Diani, Ricci, Baretta,... accompanied

with cymbals and triangles by the coryphees and corps de ballet." The new

dance received an enthusiastic reception.

From then, her fame and success increased, and she played

a succession of popular performances. On December 16, 1872, she was billed

as a feature attraction in Ned Buntline's western drama, Scouts of the

Prairie, with Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro. She and Texas

Jack fell in love, and were married on August 31, 1873. The couple settled

in a country estate in Lowell, Massachusetts and an additional home Leadville,

Colorado, though she continued to perform, both with her husband in western

dramas, and solo.

Following the death of her husband in 1880 in Leadville,

she returned to Lowell and lived quietly with her sister. She died of cancer

in 1886, and is buried in Lowell. |

.. . . |

|

All articles submitted to the "Brimstone

Gazette" are the property of the author, used with their expressed permission.

The Brimstone Pistoleros are not

responsible for any accidents which may occur from use of loading

data, firearms information, or recommendations published on the Brimstone

Pistoleros web site. |

|