American Old West

from Wikipedia

| The American Old West (often referred to as the Far West,

Old West or Wild West) comprises the history, geography, people, lore,

and cultural expression of life in the Western United States, most often

referring to the period of the later half of the 19th century, between

the American Civil War and the end of the century. After the 18th century

and the push beyond the Appalachian Mountains, the term is generally applied

to anywhere west of the Mississippi River in earlier periods and westward

from the frontier strip toward the later part of the 19th century. More

broadly, the period stretches from the early 19th century to the end of

the Mexican Revolution in 1920.

Through treaties with foreign nations and native peoples,

political compromise, technological innovation, military conquest, establishment

of law and order, and the great migrations of foreigners, the United States

expanded from coast to coast (Atlantic Ocean to Pacific Ocean), fulfilling

advocates' belief in Manifest Destiny. In securing and managing the West,

the U.S. federal government greatly expanded its powers, as the nation

evolved from an agrarian society to an industrialized nation. First promoting

settlement and exploitation of the land, by the end of the 19th century

the federal government became a steward of the remaining open spaces. As

the American Old West passed into history, the myths of the West took firm

hold in the imagination of Americans and foreigners alike.

The term "Old West" |

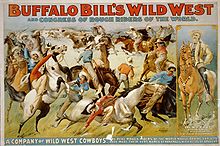

The cowboy

.. .. ..

the quintessential symbol of

the American Old West, circa 1888. |

The American frontier moved gradually

westward decades after the settlement of the first immigrants on the Eastern

seaboard in the 17th century. The "West" was always the area beyond that

boundary. Scholars, however, sometimes refer to the Old West as the region

of the Ohio and Tennessee valleys during the 18th century, when the frontier

was being contested by Britain, France, and the American colonies. Most

often, however, the "American Old West", the "Old West" or "the Great West"

is used to describe the area west of the Mississippi River during the 19th

century.

Acquiring the Frontier

Advancing frontier and the Louisiana

Purchase

During European settlement of North

America in the 17th century, the western frontier was the crest of the

Appalachian Mountains, the initial geographical impediment to expansion.

While the eastern seaboard was being tamed, the area west of these mountains

received little concern and speculation. After the Revolutionary War, the

conflict among European powers over the vast American continent and its

riches gave way to the new nation of the United States. With peace came

an impetus for westward expansion, as veterans returned to areas seen during

the war, and land hungry settlers traveled to newly available lands in

New York and across the Appalachians.

At the beginning of the 19th century,

the American frontier was approximately along the Mississippi River, which

bisects the continental United States north-to-south from just west of

the Great Lakes to the delta near New Orleans. St. Louis, Missouri was

the largest town on the frontier, the gateway for travel westward, and

a principal trading center for Mississippi River traffic and inland commerce.

The new nation began to exercise

some power in domestic and foreign affairs. The British had been driven

out of the East after the American Revolutionary War but remained in Canada

and threatened to expand into the Northwest. The French had left the Ohio

Valley but still owned the Louisiana Territory from the Mississippi River

west to the Rockies, including the strategic port of New Orleans. Spain's

dominion (New Spain) included Florida and the territories from present-day

Texas to California along the southern tier and up to what later would

be Utah and Colorado.

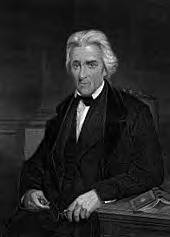

| With a stroke of the pen, Thomas

Jefferson, the third president of the United States (elected in 1800),

more than doubled the size of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase

of 1803 which acquired land France had acquired from Spain just three years

earlier. Napoleon Bonaparte had begun to consider it a liability, since

the slave rebellion in Haiti and tropical disease undermined his Caribbean

adventures. Robert R. Livingston, American ambassador to France, negotiated

the sale with French foreign minister Talleyrand, who stated, "You have

made a noble bargain for yourselves, and I suppose you will make the most

of it".

The price was $15 million (about

$0.04 per acre), including the cost of settling all claims against France

by American citizens. The purchase was controversial. Many of the Federalist

Party, the dominant political party in New England, thought that the territory

was "a vast wilderness world which will... prove worse than useless to

us" and spread the population across an ungovernable land, weakening federal

power to the detriment of New England and the Northeast. But the Jeffersonians

thought the territory would help maintain their vision of the ideal republican

society, based on agricultural commerce, governed lightly and promoting

self-reliance and virtue.

Jefferson quickly ordered exploration

and documentation of the vast territory. He charged Lewis and Clark to

lead an expedition, starting in 1804, to "explore the Missouri River, and

such principal stream of it, as, by its course and communication with the

waters of the Pacific Ocean; whether the Columbia, Oregon, |

Thomas Jefferson

Third President of the United States |

Colorado or any other river may offer

the most direct and practicable communication across the continent for

the purposes of commerce". Jefferson also instructed the expedition to

study the region's native tribes (including their morals, language, and

culture), weather, soil, rivers, commercial trading, animal and plant life.

The principal commercial goal was

to find an efficient route to connect American goods and natural resources

with Asian markets, and perhaps to find a means of blocking the growth

of British fur trading companies into the Oregon Country. Asian merchants

were already buying sea otter pelts from Pacific coast traders for Chinese

customers. An expansion of inland fur trading was also anticipated. With

news spreading of the expedition's findings, entrepreneurs like John Jacob

Astor immediately seized the opportunity and expanded fur trading operations

into the Pacific Northwest. Astor's "Fort Astoria" (later Fort George),

at the mouth of the Columbia River, became the first permanent white settlement

in that area. However, during the War of 1812, the rival North West Company

(a British-Canadian company) bought the camp from Astor's agents as they

feared the British would destroy an American camp. For a while, Astor's

fur business suffered. But he rebounded by 1820, took over independent

traders to create a powerful monopoly, and left the business as a multi-millionaire

in 1834, reinvesting his money in Manhattan real estate.

Fur trade

The quest for furs was the primary

commercial reason for the exploration and colonizing of North America by

the Dutch, French, and English. The Hudson's Bay Company, promoting British

interests, often competed with French traders who had arrived earlier and

had been already trading with indigenous tribes in the northern border

region of the colonies. This competition was one of the contributing factors

to the French and Indian War in 1763. British victory in the war led to

the expulsion of the French from the American colonies. French trading

continued, however, based in Montreal. Astor's move into the Northwest

was a major American attempt to compete with the established French and

English traders.

As the frontier moved westward,

trappers and hunters moved ahead of settlers, searching out new supplies

of beaver and other skins for shipment to Europe. The hunters proceeded

and followed Lewis and Clark to the Upper Missouri and the Oregon territory;

they formed the first working relationships with the Native Americans in

the West. They also added extensive knowledge of the Northwest terrain,

including the important South Pass through the central Rocky Mountains.

Discovered about 1812, it later became a major route for settlers to Oregon

and Washington.

The War of 1812 did little to change

the boundaries of the United States and British territories, but its conclusion

led to the nations' agreement to make the Great Lakes neutral waters to

both navies. Furthermore, competing commercial claims by England and the

U.S. led to the Anglo-American Convention of 1818. This resulted in their

sharing the Oregon territory until a decades later resolution. By 1820,

with the fur trade depressed, distances to supply increasing, and conflicts

with native tribes rising, the trading system was overhauled by Donald

Mackenzie of the North West Company and by William H. Ashley. Previously,

Indians caught the animals, skinned them, and brought the furs to trading

posts such as Fort Lisa and Fontenelle's Post, where trappers sent the

goods down river to St. Louis. In exchange for the furs, Indians typically

received calico cloth, knives, tomahawks, awls, beads, rifles, ammunition,

animal traps, rum, whiskey, and salt pork.

The new "brigade-rendezvous" system,

however, sent company men in "brigades" cross-country on long expeditions,

bypassing many tribes. It also encouraged "free trappers" to explore new

regions on their own. At the end of the gathering season, the trappers

would "rendezvous" and turn in their goods for pay at river ports along

the Green River, the Upper Missouri, and the Upper Mississippi. St. Louis

was the largest of the rendezvous towns. An early chronicle described the

gathering as "one continued scene of drunkenness, gambling, and brawling

and fighting, as long as the money and the credit of the trappers last."

Trappers competed in wrestling and shooting matches. When they would gamble

away all their furs, horses, and their equipment, they would lament, "There

goes hos and beaver." By 1830, however, fashions changed in Europe and

beaver hats were replaced by silk hats, sharply reducing the need for American

furs. Thus ended the era of the "Mountain men", trappers and scouts such

as Jedediah Smith (who had traveled through more unexplored western land

than any non-Indian and was the first American to reach California overland).

The trade in beaver fur virtually ceased by 1845.

Settling the West

Federal government and the West

While the profit motive dominated

the movement westward, the Federal government played a vital role in securing

land and maintaining law and order, which allowed the expansion to proceed.

Despite the Jeffersonian aversion and mistrust of federal power, it bore

more heavily in the West than any other region, and made possible the fulfillment

of Manifest Destiny. Since local governments were often absent or weak,

Westerners, though they grumbled about it, depended on the federal government

to protect them and their rights, and displayed little of the outright

antipathy of some Easterners to Federalism.

The federal government established

a sequence of actions related to control over western lands. First, it

acquired western territory from other nations or native tribes by treaty,

then it sent surveyors and explorers to map and document the land, next

it ordered federal troops to clear out and subdue the resisting natives,

and finally, it had bureaucracies manage the land, such as the Bureau of

Indian Affairs, the Land Office, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Forest

Service. The process was not a smooth one. Indian resistance, sectionalism,

and racism forced some pauses in the process of westward settlement. Nonetheless,

by the end of the 19th century, in the process of conquering and managing

the West, the federal government amassed great size, power, and influence

in national affairs.

Early scientific exploration

and surveys

A major role of the federal government

was sending out surveyors, naturalists, and artists into the West to discover

its potential. Following the Lewis and Clark expeditions, Zebulon Pike

led a party in 1805-6, under the orders of General James Wilkinson, commander

of the western American army. Their mission was to find the head waters

of the Mississippi (which turned out to be Lake Itasca, and not Leech Lake

as Pike concluded). Later, on other journeys, Pike explored the Red and

Arkansas Rivers in Spanish territory, eventually reaching the Rio Grande.

On his return, Pike sighted the peak named after him, was captured by the

Spanish and released after a long overland journey. Unfortunately, his

documents were confiscated to protect territorial secrets and his later

recollections were rambling and not of high quality. Major Stephen H. Long

led the Yellowstone and Missouri expeditions of 1819-1820, but his categorizing

of the Great Plains as arid and useless led to the region getting a bad

reputation as the "Great American Desert", which discouraged settlement

in that area for several decades.

In 1811, naturalists Thomas Nuttall

and John Bradbury traveled up the Missouri River with the Astoria expedition,

documenting and drawing plant and animal life. Later, Nuthall explored

the Indian Territory (Oklahoma), the Oregon Trail, and even Hawaii. His

book A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory was an important

account of frontier life. Although Nuthall was the most traveled Western

naturalist before 1840, unfortunately most of his documentation and specimens

were lost. Artist George Catlin traveled up the Missouri as far as present-day

North Dakota, producing accurate paintings of Native American culture.

He was supplemented by Karl Bodmer, who accompanied the Prince Maximilian

expedition, and made compelling landscapes and portraits. In 1820, John

James Audubon traveled about the Mississippi Basin collecting specimens

and making sketches for his monumental books Birds of America and The Viviparous

Quadrupeds of North America, classic works of naturalist art. By 1840,

the discoveries of explorers, naturalists, and mountain men had produced

maps showing the rough outlines of the entire West to the Pacific Ocean.

Mexican rule and Texas independence

Criollo and mestizo settlers of

New Spain declared their independence in 1810 (finally obtaining it in

1821) from Spain's crumbling American colonial empire in the Americas (which

were not yet thought of as being divided in North, Central and South America),

forming the new nation of Mexico which included the New Mexico territory

at its north. A hoped for result of Mexico's independence was more open

trade and better relations with the United States where previously Spain

had enforced its border strictly and had arrested American traders who

ventured into the region. After Mexico's independence, large caravans began

delivering goods to Santa Fe along the Santa Fe Trail, over the 870-mile

(1,400 km) journey which took 48 days from Kansas City, Missouri (then

known as Westport).[24] Santa Fe was also the trailhead for the "El Camino

Real" (the King's Highway), a major trade route which carried American

manufactured goods southward deep into Mexico and returned silver, furs,

and mules northward (not to be confused with another "Camino Real" which

connected the missions in California). A branch also ran eastward near

the Gulf (also called the Old San Antonio Road). Santa Fe also connected

to California via the Old Spanish Trail.

The Mexican government began to

attract Americans to the Texas area with generous terms. Stephen F. Austin

became an "empresario," receiving contracts from the Mexican officials

to bring in immigrants. In doing so, he also became the de facto political

and military commander of the area. Tensions rose, however, after an abortive

attempt to establish the independent nation of Fredonia in 1826. William

Travis, leading the "war party," advocated for independence from Mexico,

while the "peace party" led by Austin attempted to get more autonomy within

the current relationship. When Mexican president Santa Anna shifted alliances

and joined the conservative Centralist party, he declared himself dictator

and ordered soldiers into Texas to curtail new immigration and unrest.

However, immigration continued and 30,000 Americans with 3,000 slaves arrived

in 1835. A series of battles, including at the Alamo, at Goliad, and at

the San Jacinto River, led to independence and the establishment of the

Republic of Texas in 1836. The U.S. Congress, however, refused to annex

Texas, stalemated by contentious arguments over slavery and regional power.

Texas remained an independent country, led by Sam Houston, until it became

the 28th state in 1845. Mexico, however, viewed the establishment of the

statehood of Texas as a hostile act, helping to precipitate the Mexican

War.

The Trail of Tears

| The expansion of migration into

the Southeast in the 1820s and 1830s forced the federal government to deal

with the "Indian question." By 1837 the "Indian Removal policy" began,

to implement the act of Congress signed by Andrew Jackson in 1830. The

forced march of about twenty Native American tribes included the "Five

Civilized Tribes" (Creek, Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Seminole).

They were pushed beyond the frontier and into the "Indian Territory" (which

later became Oklahoma). Of the approximate 70,000 Indians removed, about

20% died from disease, starvation, and exposure on the route. This exodus

has become known as The Trail of Tears (in Cherokee "Nunna dual Tsuny,"

"The Trail Where they Cried"). The impact of the removals was severe. The

transplanted tribes had considerable difficulty adapting to their new surroundings

and sometimes clashed with the tribes native to the area. In addition,

the Smallpox Epidemic of 1837 decimated the tribes of the Upper Missouri,

weakening them, and allowing immigrants easier access to those lands.

The Indian removals were justified

by two prevailing philosophies. The "superior race" theory contended that

"inferior" peoples (i.e., natives) held land in trust until a "superior

race" came along which would be a more productive steward of the land.

Humanitarians espoused a second theory stating that the removal of natives

would take them away from the contaminating influences of the frontier

and help preserve their culture. Neither theory showed any understanding

of the natives' intimate connection with their land nor the deadly effect

of social and physical uprooting. For example, tribes were dependent on

local animals and plants for their food and their medicinal and cultural

purposes, which were often unavailable after moving. |

President Andrew Jackson |

In 1827, the Cherokee, on the basis

of earlier treaties, declared themselves a sovereign nation within the

boundaries of Georgia. When the Georgia state government ignored the declaration

and annexed the land, the Cherokee took their case to the U.S. Supreme

Court. The court ruled Georgia's laws null and void in the Cherokee nation,

but the state ignored the ruling. The court also ruled that the tribes

were "domestic dependent nations" and could not make treaties with other

nations. Furthermore, it was up to the federal government to protect those

rights, making the tribes, in effect, wards of the federal government.

President Jackson, having just signed the Indian Removal Act, failed to

enforce the court ruling, illegally abdicating to the states the right

to make policy regarding the tribes. In effect, Jackson refused to honor

the federal government's commitment to protect the southern tribes and

to act in its proper role in dealing with the tribes as sovereign, though

dependent, nations. Jackson justified his actions by stating that Indians

had "neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the

desire of improvements."

The only way for a Native American

to avoid removal was to accept the federal offer of 640 acres (2.6 km2)

or more of land (depending on family size) in exchange for leaving the

tribe and becoming a U.S. citizen subject to state law and federal law.

However, many natives who took the offer were defrauded by "ravenous speculators"

who stole their claims and sold their land to whites. In Mississippi alone,

fraudulent claims reached 3,800,000 acres (15,400 km2). Some of those who

refused to move or take the offer found sanctuary for a while in remote

areas. To motivate natives reluctant to move, the federal government also

promised rifles, blankets, tobacco, and cash. Of the five tribes, the Seminole

offered the most resistance, hiding out in the Florida swamps and waging

a war which cost the U.S. Army 1,500 lives and $20 million. Through war,

abandonment, and the removal policy, the federal government acquired about

442,800,000 acres (1,792,000 km2) of native land in the East from 1776

to 1842.

The Antebellum West

Indian policy and attitudes

No sooner had the federal government

created the "Indian Territory", the whites began to encroach upon the boundaries,

traders began to sell prohibited liquor and settlers took shortcuts across

Indian land on their way to Oregon and California. As the migrants moved

across the Great Plains, their livestock trampled Indian land and ate crops.

Some tribes struck back by raiding livestock and by demanding payment from

settlers crossing their land. The federal government attempted to reduce

tensions and create new tribal boundaries in the Great Plains with two

new treaties in the early 1850s. The Treaty of Fort Laramie established

tribal zones for the Sioux, Cheyennes, Arapahos, Crows, and others, and

allowed for the building of roads and posts across the tribal lands. A

second treaty secured safe passage along the Santa Fe Trail for wagon trains.

In return, the tribes would receive, for ten years, annual compensation

for damages caused by whites.

The Kansas and Nebraska territories

also became contentious areas as the federal government sought those lands

for the future transcontinental railroad. In the Far West settlers began

to occupy land in Oregon and California before the federal government secured

title from the native tribes, causing considerable friction. In Utah, the

Mormons also moved in before federal ownership was obtained. During their

flight West, the Mormons established an outpost called Winter Quarters

with permission from Big Elk of the Omaha tribe. This set a precedent for

such agreements; however, when the Mormons exhausted local timber supplies

they were asked to move from the land. Their occupancy in the area that

soon became the Nebraska Territory lasted from 1846 to 1848.

Native American chiefs, 1865 |

A new policy of establishing reservations

came gradually into shape after the boundaries of the "Indian Territory"

began to be ignored. In providing for Indian reservations, Congress and

the Office of Indian Affairs hoped to detribalize native Americans and

prepare them for integration with the rest of American society, the "ultimate

incorporation into the great body of our citizen population." This allowed

for the development of dozens of riverfront towns along the Missouri River

in the new Nebraska Territory, which was carved from the remainder of the

Louisiana Purchase after the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Influential pioneer towns

included Omaha, Nebraska City and St. Joseph.

White attitudes towards Indians

during this period ranged from extreme malevolence ("the only good Indian

is a dead Indian") to misdirected humanitarianism (Indians live in "inferior"

societies and by assimilation into white society they can be redeemed)

to somewhat realistic (Native Americans and settlers could co-exist in

separate but equal societies, dividing up the remaining |

western land). Dealing with nomadic

tribes complicated the reservation strategy and decentralized tribal power

made treaty making difficult among the Plains Indians. Conflicts erupted

in the 1850s, resulting in the Indian Wars.

Frémont's expeditions

John Charles Frémont, son-in-law

of powerful Missouri senator and expansionist Thomas Hart Benton, led a

series of expeditions in the mid 1840's which answered many of the outstanding

geographic questions about the West. He crossed through the Rocky Mountains

by five different routes, reached deep into the Oregon territory, traveled

the length of California, and into Mexico below Tucson. With the help of

legendary scouts Christopher "Kit" Carson and Thomas "Broken Hand" Fitzpatrick,

and German cartographer Charles Preuss, Frémont produced detailed

maps, filled in gaps of knowledge, and provided route information that

fostered the "Great Migrations" to Oregon, California, and the Great Basin.

He also disproved the existence of the mythical Rio San Buenaventura, featured

on old maps, which was a large river believed to drain all of the West

and which exited at San Francisco into the Pacific.

Manifest Destiny and the early

migrations

Manifest Destiny was the belief

that the United States was pre-ordained by God to expand from the Atlantic

coast to the Pacific coast. The concept was expressed during Colonial times,

but the term was coined by newspaperman John O'Sullivan, and became a rallying

cry for expansionists in the 1840s. It was a moral/religious as well as

political/economic justification for growth, regardless of the social and

legal consequences for Native Americans. Implicit is the position that

the American claim supersedes?by God's favor?that of foreign nations or

the native peoples. O'Sullivan wrote, "Away, away with all these cobweb

tissues of rights of discovery, exploration, settlement, continuity, etc....

The American claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread

and to possess the whole continent which Providence has given us for the

development of the great experiment of liberty and federative self-government

entrusted to us".

The Polk and Tyler administrations

successfully promoted this nationalistic doctrine over sectionalists and

others who objected for moral reasons or over concerns about the spread

of slavery. Starting with the annexation of Texas, the expansionists got

the upper hand. To gain the acceptance of Northerners, Texas was even promoted

by expansionists as a place where slavery could be concentrated, and from

where blacks and slavery would eventually leave the U.S. entirely, solving

the problem forever.

Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, among

others, did not vote for conquest and expansion, and preferred co-existence

with friendly foreign powers sharing the continent. John Quincy Adams believed

the Texas annexation to be "the heaviest calamity that ever befell myself

and my country". However, Manifest Destiny's popularity in the Midwest

states and the addition of federal encouragement overcame the opposition

and created a climate which helped start the "Great Migrations" to Oregon,

California, and the Great Basin.

Also spurring settlers westward

were the emigrant "guide books" of the 1840s featuring route information

supplied by the fur traders and the Frémont expeditions, and promising

fertile farm land beyond the Rockies. Independence, Missouri became the

starting point for caravans of "Chicago" and "Prairie Schooner" wagons

which traveled the Oregon and California trails. Starting in late 1848

over 250,000 settlers passed over the California trail to California. The

trip was slow and arduous, but unlike the depiction in films, generally

absent of Indian attacks. One Oregon pioneer wrote, "Our journey is ended.

Our toils are over. But... no tongue can tell, nor pen describe the heart

rending scenes through which we passed". On the 2,000-mile (3,200 km) journey,

settlers had to overcome extreme climate, lack of food and clean water,

disease, broken down wagons, and exhausted draft animals. The Oregon territory,

filling up with Americans, was ceded to the U.S. in 1846 by Great Britain,

which was anxious to fix the northern boundary at the 49th parallel. Oregon

gained statehood in 1859.

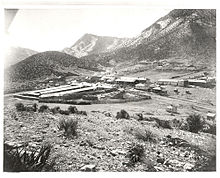

Brigham Young, also influenced by

Frémont's discoveries and seeking to escape persecution, led his

followers of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (the "Mormons")

to the valley of the Great Salt Lake, bypassed by other immigrants headed

to Oregon, because of its aridity. Eventually, nearly one hundred Mormon

settlements sprang up in what Young called "Deseret", which later became

Utah, California, Nevada, Arizona, and Nebraska. The Salt Lake City settlement

served as the hub of their network, and was proclaimed "Zion, the seat

of God's kingdom on earth". The communalism and advanced farming practices

of the Mormons enabled them to succeed in a region other settlers rejected

as too harsh but which Frémont believed to have great potential.

During the gold rushes of the 1850s, Salt Lake City became an important

supply point, adding to its economic strength.

In California, the twenty-one mission

settlements established by the Catholic Church had failed to attract sufficient

Mexican settlers who had viewed the region as too remote. The Spanish aristocracy

(the "californios") controlled the territory through vast land grants on

which large cattle ranches spread. Manned mostly by Christianized Indians

supervised by the friars, the ranches supplied English and American merchant

ships with hides and tallow. The few Americans in the area were mostly

traders, merchants, and sailors, many from "Yerba Buena" (renamed San Francisco

in 1846). Although Presidents Jackson and Tyler's efforts to buy California

from Mexico had failed, American settlers started to enter the territory

by 1841. The Bartleson-Bidwell Party brought the first overland family

migrations to Sacramento, California, followed by several more caravans

which established the California Trail. Thousands of settlers and miners

made the trip in the following decade after the discovery of gold. When

Frémont's third expedition brought him to California in 1845, he

joined the Bear Flag Revolt, and allied with other American forces, captured

and controlled considerable California territory. In 1847, a counter-revolt

by "rancheros" failed. At the same time that the Mexican War was underway

in the central Southwest, Mexico decided to formally cede California to

the U.S. in the Treaty of Cahuenga.

The Mexican War

A crisis with Mexico had been brewing from the time Texas

won its independence in 1836. The annexation of Texas by the United States

brought feelings on both sides to a boil. Additionally, the two nations

disputed the border, the U.S. insisting on the Rio Grande and Mexico claiming

the Nueces River, 150 miles (240 km) north. Also, an international commission

decided that American settlers were owed damages in the millions of dollars

for past wrongs by the Mexican government, which it refused to pay. President

Polk attempted to use the debts as leverage in offering to buy the Mexican

territories of New Mexico and California, while he made a show of force

along the border area. Negotiations got nowhere, and as Polk prepared to

ask Congress to declare war, the Mexican cavalry began an attack on American

outposts. After the declaration of war, Whigs accused the President of

imperialism and claimed that the administration had employed "an artful

perversion of truth—a disingenuous statement of facts to make people believe

a lie". Northerners also feared the extension of slavery into the new territories,

though the linchpin of slavery—the plantation—seemed improbable in the

dusty plains of Texas.

| General (and later president) Zachary Taylor was ordered

to the scene and his troops forced the Mexicans back to the Rio Grande.

Then he advanced into Mexico where several battles ensued. Also General

Winfield Scott undertook a naval assault on Veracruz, then marched his

12,000 man force west to Mexico City, winning the final battle at Chapultepec.

Some advocated for the complete take over of Mexico by the U.S., but practical

arguments as well as racism prevented the attempt. The "Cincinnati Herald"

voiced the racist sentiment asking what would the U.S. do with millions

of Mexicans "with their idol worship, heathen superstition, and degraded

mongrel races?"

The surrender by Mexico took place on September 17, 1847.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in 1848, ceded the territories

of California and New Mexico (which included the states-to-be of Utah,

Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming) to the

United States for $18.5 million (which included the assumption of claims

against Mexico by settlers). The Gadsden Purchase in 1853, covering southern

Arizona and New Mexico, pushed the border southward and acquired land for

an anticipated railroad route, and had the unintended effect of heightening

conflicts with southern Apaches now habitating U.S. territory. The Mexican

War was the smallest but deadliest of American wars—one in six American

soldiers died from bullets or disease—but the spoils of that war were substantial.

The completed Mexican cession covered over half a million square miles

and increased the size of the U.S. by nearly 20%. Managing the new territories

and dealing with the slavery issue were challenges which lay ahead. The

Compromise of 1850 kept California a free state and allowed Utah and New

Mexico to make their own decisions regarding slavery. It also imposed some

border adjustments. |

Zachary Taylor |

Gold rushes and the mining industry

On January 24, 1848, James Marshall

discovered gold in the tailrace of the mill he had built for John Sutter.

Sutter, a Swiss entrepreneur, had acquired a land grant for over 49,000

acres (200 km2) near present day Sacramento and built himself what was,

in effect, an independent principality. According to Sutter's reminiscence,

"Marshall pulled out of his trousers pocket a white cotton rag which contained

something rolled up in it... Opening the cloth, he held it before me in

his hand... 'I believe this is gold,' said Marshall, 'but the people at

the mill laughed at me and called me crazy.' I carefully examined it and

said to him: 'Well, it looks like gold. Let us test it.'" Prior to this

discovery, gold mining in the United States had been limited to primitive

mines in the Southeast, especially in Georgia. Word spread quickly across

the United States, after Polk told Congress in December 1848, "The accounts

of the abundance of gold in that territory are of such an extraordinary

character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by

the authentic reports of officers in the public service."

Gold prospector |

The word also reached experienced

miners in South America and Europe, who quickly headed to California. Thousands

of "Forty-Niners" reached California, many along the California trail,

boosting the population from about 14,000 in 1848 to over 200,000 in 1852.

San Francisco was the main port of arrival, with Asians, South Americans,

Australians, and Europeans making long ocean journeys, and the town grew

from 800 to 20,000 people in eighteen months, with only a fractional number

of women and children. Experienced foreign miners sometimes taught the

willing American amateurs, but most newcomers arrived, grabbed some supplies,

and headed willy-nilly to the gold camps without the slightest idea of

what mining entailed.

As in many other boomtowns, rapid

growth in San Francisco resulted in hastily erected housing, mob rule,

vigilante justice, hyper-inflated prices, environmental degradation, and

considerable squalor. Field conditions for miners were even worse. They

lived in log cabins and tents, and worked in all kinds of weather, suffering

disease without treatment. Supplies were expensive and food poor, subsisting

mostly of pork, beans, and whiskey. These highly male, transient communities

with no established institutions were prone to high levels of violence,

drunkenness, profanity, and greed-driven behavior. A weekend's entertainment

with a prostitute and plentiful drink could cost hundreds of dollars, not

including gambling losses, wiping out a month or more of found gold. |

Without courts or law officers in

the mining communities to enforce claims and justice, miners developed

their own ad hoc legal system, based on the "mining codes" used in other

mining communities abroad. Each camp had its own rules and often handed

out justice by popular vote, sometimes acting fairly and at times exercising

vigilantism—with Indians, Mexicans, and Chinese generally receiving the

harshest sentences. As miner John Cowden wrote, "Very few ever think of

stealing in the country of plenty and those who do so are immediately strung

up."

| Prostitution grew rapidly in the

Western boom towns, attracting many female workers from the East and Mid-West.

In many towns, the ratio of "honest" women to men was 1 to 100, thereby

encouraging the flesh trade. Until the 1890s, madams predominately ran

the businesses, after which "pimps" took over, and the treatment of the

women generally declined. The openness of bordellos in western towns depicted

in films was somewhat realistic, though the true appearance of most prostitutes

was far less attractive than those depicted by Hollywood starlets. Gambling

and prostitution were central to life in these western towns, and only

later?as the female population increased, reformers moved in, and other

civilizing influences arrived?did prostitution become less blatant and

less common.

The Gold Rush radically changed

the California economy and brought in an array of professionals, including

precious metal specialists, merchants, doctors, and attorneys, who supplemented

the numerous miners, saloonkeepers, gamblers, and prostitutes. A San Francisco

newspaper stated, "The whole country... resounds to the sordid cry of gold!

Gold! Gold! while the field is left half planted, the house half built,

and everything neglected but the manufacture of shovels and pick axes."

Gold |

San Francisco harbour c. 1850.Between

1847 and 1870, the population of

San Francisco increased

from 500 to 150,000. |

fever was a widespread affliction among

all classes. Black Elk recalled, gold was "the yellow metal that makes

whites crazy." Later rushes, though notable, possessed less of the "lunacy"

and urgency of the California strikes. The extraordinary size of early

finds (including nuggets of over 20 lb (9.1 kg). each), the surprise of

the finds, and the abundance of surface gold helps explain that irrational

fervor. Most of the gold discoveries of the California Gold Rush were achieved

through placer mining, the finding of nuggets and grains loosened from

rock by nature through erosion and carried down streams from the Sierras.

This was relatively easier and required less capital and expertise than

vein mining, which required drilling down into rock and breaking gold and

silver loose. Over 250,000 miners found a total of more than $200 million

in gold in the five years of the California Gold Rush. As thousands arrived,

however, fewer and fewer miners struck their fortune, and most ended exhausted

and broke.

Camps spread out north and south

of the American River and eastward into the Sierras. In a few years, nearly

all of the independent miners were displaced as mines were purchased and

run by mining companies, who then hired low-paid salaried miners. As gold

became harder to find and more difficult to extract, individual prospectors

gave way to paid work gangs, specialized skills, and mining machinery.

Bigger mines, however, caused greater environmental damage. In the mountains,

shaft mining predominated, producing large amounts of waste. Independent

miners began to leave California in the 1850s as mines gave out, and moved

on to new finds in Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado.

An exception were the Chinese. After white prospectors left the placer

mining areas, many Chinese miners, previously excluded by racism, found

the freedom to buy up the old claims and re-work them.

The discovery of the Comstock Lode,

containing vast amounts of silver, resulted in the Nevada boomtowns of

Virginia City, Carson City, and Silver City. The wealth from silver, more

than from gold, fueled the maturation of San Francisco in the 1860s and

helped the rise of some of its wealthiest families.

Following the California and Nevada

discoveries, miners left those areas and hunted for gold along the Rockies

and in the southwest. Soon gold was discovered in Colorado, Utah, Arizona,

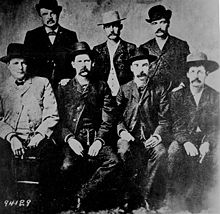

New Mexico, Idaho, Montana, and South Dakota (by 1864). Deadwood, South

Dakota, in the Black Hills, was an archetypical late gold town, founded

in 1875. In 1876, Wild Bill Hickok, accompanied by Calamity Jane, came

to town and cemented Deadwood's fame by being murdered there ten days later.

Tombstone, Arizona was another notorious mining town. Silver was discovered

there in 1877, and by 1881 the town had a population of over 10,000. Wyatt

Earp and his brothers arrived in 1880, became actively involved as Republicans,

saloon owners, and real estate investors, and soon became involved in the

most famous gunfight of the Old West, the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

In the aftermath, Virgil Earp survived an assassination and Morgan Earp

was hunted down and killed. Wyatt fled Tombstone with warrants issued against

him and drifted through California, Colorado, Idaho, Arizona, and Alaska.

In his old age, Wyatt Earp was an adviser in Hollywood for western movies,

which helped secure his legendary status.

As gold and silver played out, the

large work force of experienced miners gradually found work as industrial

miners—working copper, iron, coal, and rare earth deposits which fueled

a rapidly expanding national economy. Working the deeper mines was extremely

hazardous. Temperatures could exceed 150 °F (66 °C) below 2,000

feet (610 m) and many died from heat stroke. Poor ventilation concentrated

a toxic brew of carbon dioxide, dust, and other compounds and caused frequent

headaches and dizziness. Accidents, premature explosions, and cave-ins

were common and deadly. About half the miners had lung disorders, shortening

their lives to an average of 43 years. In the hard rock mines, accidents

annually disabled 1 of every 30 miners and killed 1 out of 80, the highest

rates of any U.S. industry.

Pony Express and telegraph

The Gold Rush and the subsequent spurt of migration to

California hastened the need for better communications across the continent.

Mail was being transported to San Francisco by ship from New York, with

a land crossing across the Isthmus of Panama, normally a month's trip.

Then the federal government provided subsidies for the development of mail

and freight delivery, and by 1856, Congress authorized road improvements

and an overland mail service to California. There was even an experiment

to use camels for transportation. Commercial wagon trains began to haul

freight out west. For mail, the Overland Mail Company was formed, using

what was called the "Butterfield route", through Texas, then New Mexico

and into Arizona, over the dangerous Apache Pass protected by Fort Bowie.

This route was abandoned by 1862, after Texas joined the confederacy, in

favor of stagecoach services established via Fort Laramie and Salt Lake

City, a 24 day journey, with Wells Fargo & Co. as the foremost provider

(initially keeping the "Butterfield" name).

| William Russell, hoping to get a government contract

for more rapid mail delivery service, started the Pony Express in 1860,

cutting delivery time to ten days. He set up over 150 stations about 15

miles (24 km) apart. Riders were required to be expert and weigh less than

125 lb (57 kg)., with an advertisement of the time asking for, "young skinny

wiry fellows, not over eighteen... willing to risk death daily... Orphans

preferred... Wages: $25 per week." If a relief rider was not available

at the next station, the rider was required to change horses and keep going.

The service was short-lived, however, as the continental

telegraph was completed on October 24, 1861, just eighteen months later.

Samuel F. B. Morse developed his telegraph system in the 1830s. It found

acceptance by the mid 1840s, and over 50,000 miles (80,000 km) of wire

were laid out to form a single national network. The telegraph and the

Morse Code made possible the instantaneous transmission of information

and the beginning of the tele-communications industry. The new national

communication system soon proved a boon to newspapers, to freight hauling,

to weather reporting, to law enforcement, and to the railroads. |

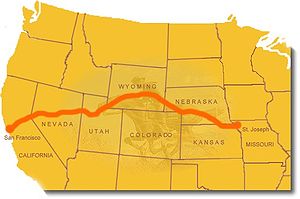

Map of Pony Express route |

Though Russell did get a government contract, his business

had considerable losses anyway and failed. After the Pony Express service

folded, mail continued by overland coach and by sea. However, Wells Fargo

(established in 1852) maintained special courier services across the Sierras

for carrying gold and mail through the 1860s, and its banking, freighting,

and business services flourished in California. It grew through the consolidation

of other overland mail companies until the opening of the transcontinental

railroad in 1869 caused Wells Fargo to realign its services and delivery

routes.

Bleeding Kansas

By the mid-1850s, the Kansas territory had a population

of only a few hundred settlers but it became the focus of the slavery question.

Of its neighboring states, Missouri was a slave state and Iowa was not.

With the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, Congress repealed the Missouri Compromise

which blocked slavery in Kansas, therefore leaving the decision up to Kansas.

The stakes were high. Adoption of slavery in Kansas would have given the

slave states a two vote majority in the Senate and abolitionists were intent

on blocking that. To influence the territorial decision, abolitionists

(also called "Jayhawkers" or "Free-soilers") financed the migration of

anti-slavery settlers. But pro-slavery advocates secured the outcome of

the territorial vote by bringing in "Border Ruffians", rowdies from Missouri

who stuffed ballot boxes and intimidated voters. The anti-slavers then

sent Sharps rifles ("Beecher's Bibles") and ammunition to supporters in

Kansas, leading to widespread violence and destruction which prompted the

New York Tribune to call the territory "Bleeding Kansas."

Dred Scott

The Dred Scott decision by the Supreme Court of the United

States in 1857 declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional and that

Congress had no authority to exclude slavery from the territories, thus

opening these areas to slavery again depending on the local vote. Despite

the efforts by presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan to influence

Kansas territorial governors to vote pro-slavery, Kansas voted to become

a free state and the thirty-fourth state of the Union in 1861. The conflict

also helped to foster the organization and development of the Republican

Party in 1856, a mixture of free-soilers, expansionists, and federalists

who opposed the extension of slavery into the Western territories. Abraham

Lincoln, an early Republican, made clear his position on slavery in the

famous Lincoln-Douglas debates which helped propel him to the presidency

in 1860, "Never forget that we have before us this whole matter of the

right or wrong of slavery in this Union, though the immediate question

is as to its spreading out into new Territories and States". Lincoln branded

slavery as a "monstrous injustice" and a "moral, social, and political

evil". In 1862, Lincoln signed a law prohibiting the spread of slavery

into all the remaining territorial possessions. During Lincoln's administration,

two other important acts were passed which impacted the West—the Homestead

Act and the Pacific Railroad Act.

Civil War in the West

At the outset of the American Civil War, Westerners looked

to the Civil War to settle the question of slavery in their territories.

But they also feared that the federal government would be too preoccupied

with the war to worry about the stability of the territorial governments

and that lawlessness might spread. The Dred Scott Decision had made the

choice of making slavery legal in all of the land west of the Mississippi

River, except for Kansas, Oregon, and California.

.

.. ..

A historical reenactment of the

Battle of Picacho Peak in Arizona |

Although most of the battles of the Civil War took place

east of the Mississippi River, a few important campaigns occurred in the

West. However, Kansas, a major area of conflict building up to the war,

was the scene of only one battle, at Mine Creek. But its proximity to Confederate

states enabled guerillas, such as Quantrill's Raiders, to attack Union

strongholds, causing considerable damage. Both sides attacked civilians,

murdering and plundering with little discrimination, creating an atmosphere

of terror.

In Texas, citizens voted to join the confederacy. Local

troops took over the federal arsenal in San Antonio, with plans to grab

the territories of northern New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado, and possibly

California. Confederate Arizona was created by Arizona citizens who wanted

protection against the Apache after the United States Army abandoned them

to go fight in the South. At the Battle of Glorieta Pass, the Confederate

campaign was defeated strategically by Union troops from Colorado and from

Fort Union. Missouri, a Union state where slavery was legal, became a |

Settlers escaping the

Dakota War of 1862 |

battleground when the pro-secession governor, against the

vote of the legislature, led troops to the federal arsenal at St. Louis.

When Confederate forces from Arkansas and Louisiana joined him, Union General

Samuel Curtis was dispatched to the area and regained Missouri for the

Union for the duration of the war.

he decreased presence of Union troops in the West left

behind untrained militias which encouraged native uprisings and skirmishes

with settlers. President Lincoln appears to have had little time to formulate

new Indian policy. Some tribes took sides in the war, even forming regiments

that joined the Union or the rebel cause, while others took the opportunity

to avenge past wrongs by the federal government. Engagements were fought

against natives in Utah against the Shoshone, all across New Mexico Territory

against Apaches and the Navajo, conflict also occurred in Oregon. Within

the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, conflicts arose among the Five Civilized

Tribes, some of whom sided with the South being slaveholders themselves.

While the question of whether western territories would

be free or slave-owning had preoccupied antebellum political debate, in

1862, Congress enacted two major laws to facilitate settlement of the West:

the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railroad Act.

The Postbellum West

Territorial governance after the Civil War

With the war over, the federal government focused on improving

the governance of the territories. It subdivided several territories, preparing

them for statehood, following the precedents set by the Northwest Ordinance

of 1787. It also standardized procedures and the supervision of territorial

governments, taking away some local powers, and imposing much "red tape",

growing the federal bureaucracy significantly.

Federal involvement in the territories was considerable.

In addition to direct subsidies, the federal government maintained military

posts, provided safety from Indian attacks, bankrolled treaty obligations,

conducted surveys and land sales, built roads, staffed land offices, made

harbour improvements, and subsidized overland mail delivery. Territorial

citizens came to both decry federal power and local corruption, and at

the same time, lament that more federal dollars were not sent their way.

Territorial governors were political appointees and beholden

to Washington so they usually governed with a light hand, allowing the

legislatures to deal with the local issues. In addition to his role as

civil governor, a territorial governor was also a militia commander, a

local superintendent of Indian affairs, and the state liaison with federal

agencies. State legislators, on the other hand, spoke for the local citizens

and they were given considerable leeway by the federal government to make

local law, except in extreme cases, as when the Federal government suppressed

polygamy by the Mormons in Utah.

These improvements to governance still left plenty of

room for profiteering. As Mark Twain wrote while working for his brother,

the secretary of Nevada, "The government of my country snubs honest simplicity,

but fondles artistic villainy, and I think I might have developed into

a very capable pickpocket if I had remained in the public service a year

or two." "Territorial rings", corrupt associations of local politicians

and business owners buttressed with federal patronage, embezzled from Indian

tribes and local citizens, especially in the Dakota and New Mexico territories.

Federal land system

In acquiring, preparing, and distributing public land

to private ownership, the federal government generally followed the system

set forth by the Land Ordinance of 1785. Federal exploration and scientific

teams would undertake reconnaissance of the land and determine Native American

habitation. Through treaty, land title would be ceded by the resident tribes.

Then surveyors would create detailed maps marking the land into squares

of six miles (10 km) on each side, subdivided first into one square mile

blocks, then into 160-acre (0.65 km2) lots. Townships would be formed from

the lots and sold at public auction. Unsold land could be purchased from

the land office at a minimum price of $1.25 per acre.

In theory, the system would provide a fair distribution

of land and reduce large accumulations of land by private owners. In reality,

speculators could exploit loopholes and acquire large tracts of land. There

was no limit to purchases of the unsold land by speculators. Furthermore,

settlers often got to the land ahead of the surveyors and became squatters,

living on land they held no title to.

As part of public policy, the government would award public

land to certain groups such as veterans, through the use of "land script".

The script traded in a financial market, often at below the $1.25 per acre

minimum price set by law, which gave speculators, investors, and developers

another way to acquired large tracts of land cheaply. Land policy became

politicized by competing factions and interests, and the question of slavery

on new lands was contentious. As a counter to land speculators, farmers

formed "claims clubs" to enable them to buy larger tracts than the 160-acre

(0.65 km2) allotments by trading among themselves at controlled prices.

The federal government also began to give away land for

agricultural colleges, Indian reservations, public institutions, and the

construction of railroads. It also gave away land when a territory became

a state, and it gave each state 30,000 acres (120 km2) for each senator

and representative.

In 1862, Congress passed three important bills that impacted

the land system. The Homestead Act granted 160 acres (0.65 km2) to each

settler who improved the land for five years, to citizens and non-citizens

including squatters, for no more than modest filing fees. If a six months

residency was complied with, the settler then had the option to buy the

parcel at $1.25 per acre. The property could then be sold or mortgaged

and neighboring land acquired if expansion was desired. Though the act

was on the whole successful, the 160-acre (0.65 km2) size of parcels was

not large enough for the needs of Western farmers and ranchers, and it

failed to address the needs of the mining and timber operations as well.

.. ..

Homesteaders |

Early on after the California Gold Rush, the federal

government decided to leave the regulation of mining claims to local governments.

This was reversed by later acts, which helped legitimate land acquisition

for all purposes but which also made it easier for speculators and swindlers,

especially in the timber and ranching industries. Given the necessity of

water for ranching, squabbles over water rights ensued and complicated

the situation. The railroads got much of the best land, and the land available

to homesteaders was not always arable or commercially useful. On the whole,

only about one-third of all Homestead Act claimants actually completed

the process of obtaining title to their land.

The Pacific Railroad Grant provided for the land needed

to build the transcontinental railroad. Since several routes were under

consideration, the amount of land so provided was huge, over 174,000,000

acres (700,000 km2). The land given the railroads alternated with government-owned

tracts saved for distribution to homesteaders. In an effort to be equitable,

the federal government reduced each tract |

to 80 acres (320,000 m2) because of its perceived higher

value given its proximity to the rail line. Railroads had up to five years

to sell or mortgage their land, after tracks were laid, after which unsold

land could be purchased by anyone. Often railroads sold some of their government

acquired land to homesteaders immediately to encourage settlement and the

growth of markets the railroads would then be able to serve. However, the

railroads were slow to build in some areas, waiting for the population

to grow adequately on its own, before selecting final routes. This caused

a "chicken-and-egg" situation which, in some cases, impeded rather than

hastened settlement. Congress also made loans to the railroads based on

the mileage of rail.

The Morrill Act provided land grants to states to build

institutions of higher education for agricultural purposes, in an effort

to stimulate rural economic growth and the education programs to support

it. The states would sell the bulk of the land to raise funds to build

the institutions.

The federal government even attempted to forest the prairies

to make better use of undesirable land. Relying on the theory that planting

trees would alter the climate enough to produce the rainfall need to sustain

the forests long term, the government encouraged homesteaders to plant

trees. When the "rain-follows-the-plow program" failed due to drought and

pests, the federal government turned instead to more practical programs

to develop irrigation, though large-scale irrigation projects came decades

later. But by the 1870s, the large land giveaways raised concerns about

the management of remaining public lands, particularly those of unique

value such as the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone, and the conservation movement

was born. In 1872, Yellowstone became the first national park in the United

States (and in the world).

Transcontinental railroad

The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 finally hastened the

transition of the transcontinental railroad from dream to reality. Existing

rail lines, particularly belonging to the Union Pacific, had already reached

westward to Omaha, Nebraska, about half way across the continent. The Central

Pacific, starting in Sacramento, California, was extended eastward across

the Sierras to link with the Union Pacific heading west. The two finally

met at Promontory Point, Utah on May 10, 1869. Leland Stanford, one of

the prime backers of the Central Pacific, hammered the golden spike in

triumph, linking the two lines. A cross-country trip was reduced from about

four months to one week by the completion of the railroad.

Building the railroad required six main activities: surveying

the route, blasting a right of way, building tunnels and bridges, clearing

and laying the roadbed, laying the ties and rails, and maintaining and

supplying the crews with food and tools. The work was highly labor intensive,

using mostly plows, scrapers, picks, axes, chisels, sledgehammers, and

handcarts. A few steam-driven machines, such as shovels, were employed

as well. Each iron rail weighed 700 lb (320 kg). and required five men

to lift. For blasting, they used gunpowder, nitroglycerine, and limited

amounts of dynamite. The Central Pacific employed over 12,000 Chinese workers,

90 percent of the work force. The Union Pacific employed mostly Irishmen.

The crews averaged about two miles (3 km) of new track per day but they

were driven to do more. Each man lifted a few tons a day of weight. In

the haste to complete the project, engineering errors caused collapsing

roadbeds and badly graded curves. Substandard rails and ties were also

serious problems. The defects became even more apparent with freight runs,

causing many accidents, and the line eventually required millions of dollars

to repair and replace bad track.

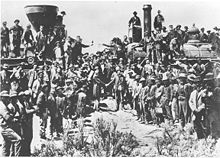

| With grants and loans, the federal government stimulated

the land and capital acquisition needed for the project. Leland Stanford,

former governor and part of a group of businessmen known as the "Big Four",

sold stock and bonds in the enterprise to finance construction, with the

help of Wall Street money men like Jay Gould who connected with investors

in the United States and Europe. The enterprise was considered risky, given

the high construction costs, and the bonds need to yield high interest

(similar to today's "junk bonds") to be attractive to investors. The huge

dollars involved in the project and the participation of so many groups

out to profit resulted in substantial corruption and influence peddling.

The owners of both construction companies, using mostly "other people's

money", insured their own profits with shady dealing and with slush funds

used to bribe government officials. |

..

The meeting of the lines on May 10, 1869 |

The worst corruption revolved around George Francis Train's

Crédit Mobilier, the construction company for the Union Pacific,

which, according to author Richard White, drew in "dozens of congressmen,

a secretary of the treasury, two vice-presidents, a leading presidential

contender, and an eventual president. It caused a scandal that remained

an issue in four presidential elections". Train's other enterprises, including

the Credit Foncier of America, Train Town and Omaha's Cozzens Hotel, succeeded,

further burnishing Train's image. While the Central Pacific-Union Pacific

railroad succeeded, other transcontinental projects failed to reach the

Pacific coast until many years later. The most notorious was the Northern

Pacific project which failed to sell its bonds, resulting in the collapse

of the Jay Cooke and Company investment house and helping to trigger the

financial Panic of 1873. The most profitable of the transcontinental lines

was the Great Northern railroad which ran along the northern tier of the

United States, providing freight service to the Northwest. The cost of

moving freight on the Great Northern was 2.88 cents per ton early on, falling

to less than. 80 cents by 1907.

Despite the engineering problems and political scandals,

the transcontinental railroad was a big success in helping to open up the

West. In the first year, 150,000 passengers made the trip for "pleasure,

health, or business" and enjoyed the "luxurious cars and eating houses"

as advertised by the Union Pacific. Settlers were encouraged with promotions

to come West on scouting trips to buy land near the line and to use the

rails for freight needs. The railroads had "Immigration Bureaus" which

advertised the "promised land" abroad. Railroad "Land Departments" sold

land on easy terms. The Great Plains, a harder "sell" than California or

Oregon, was promoted as "prairie which is ready for the plow" and "a flowery

meadow" only requiring "diligent labor and economy to ensure an early reward."

The transcontinental railroad spurred the development

of trunk and feeder lines and the rapid growth of Omaha specifically, creating

a rail network extending from the city that eventually reached over most

of the West. The railroads made possible the transformation of the United

States from an agrarian society to a modern industrial nation. Not only

did they bring eastern products west and agricultural products east, but

they also helped the establishment of western branches of eastern companies.

Mail order businesses grew rapidly, bringing city products to rural families,

sometimes dominating local companies and forcing them out of business.

The building and the operation of railroads, which required vast amounts

of coal and lumber, spurred the timber and mining industries. Most industries

benefited from the lower costs of transportation and the expanding markets

made possible by the railroads. Railroads also had a profound social effect.

Rail travel brought immigrant families to the West as women were less intimidated

by the rail journey west than by wagon. The greater numbers of women and

children migrating west helped stabilize and tame some of the wild frontier

towns, as these settlers organized and demanded schools, law enforcement,

churches, and other institutions supportive of family life.

Life on the Frontier

Migration after the Civil War

| After the Civil War, many from the East Coast and Europe

were lured west by reports from relatives and by extensive advertising

campaigns promising "the Best Prairie Lands", "Low Prices", "Large Discounts

For Cash", and "Better Terms Than Ever!". The new railroads provided the

opportunity for migrants to go out and take a look, with special "land

exploring tickets", the cost of which could be applied to land purchases

offered by the railroads. As one farm wife stated, "There's nothing up

there but Indians and rattlesnakes and blue northers and prairie fires".

The truth was that farming the plains was indeed more difficult than back

east. Water management was more critical, lightning fires were more prevalent,

the weather was more extreme, rainfall was less predictable.

Most migrants, however, put those concerns aside. Their

chief motivation to move west was to find a better economic life than the

one they had. Farmers sought larger and more fertile areas; merchants and

tradesman new customers and less competitive markets; laborers higher paying

work and better |

Migration after the Civil War |

conditions. The major exception was the Mormons, who sought

a religious and economic Utopia, free of persecution, which would allow

their entire community to thrive. In many cases, migrants sank their roots

in communities of similar religious and ethnic backgrounds. For example,

many Finns went to Minnesota and Michigan, Swedes to South Dakota, Norwegians

to North Dakota, Irish to Montana, Chinese to San Francisco, German Mennonites

in Kansas, and German Jews to Portland, Oregon.

The California Gold Rush set off large migrations of Hispanic

and Asian people which continued after the Civil War. Chinese migrants,

many of whom were impoverished peasants, provided the major part of the

workforce for the building of Central Pacific portion of the transcontinental

railroad. They also worked in mining, agriculture, and small businesses,

and many lived in San Francisco. Significant numbers of Japanese also arrived

in California. Some migrants intended to make their fortune and return

home and others sought to stay and start a new life.

.. ..

Buffalo soldier |

Many Hispanics who had been living in the former territories

of New Spain, lost their land rights to fraud and governmental action when

Texas, New Mexico, and California were formed. In some cases, Hispanics

were simply driven off their land. In Texas, the situation was most acute,

as the "Tejanos", who made up about 75% of the population, ended up as

laborers employed by the large white ranches which took over their land.

In New Mexico, only six percent of all claims by Hispanics were confirmed

by the Claims Court. As a result, many Hispanics became permanently migrating

workers, seeking seasonal employment in farming, mining, ranching, and

on the railroads. Border towns sprang up with barrios of intense poverty.

In response, some Hispanics joined labor unions, and in a few cases, led

revolts. The California "Robin Hood", Joaquin Murieta, led a gang in the

1850s which burned houses, killed miners, and robbed stagecoaches. In Texas,

Juan Cortina led a 20-year campaign against Texas land grabbers and the

Texas Rangers, starting around 1859. Instead of the reality of Hispanic

life, in the United States the public's image became one of quaint peasants

happy with their lot. |

Among the first African-Americans to arrive in the West

were deserting sailors and slaves of white prospectors who came during

the California Gold Rush, numbering about four thousand by 1860. However,

the number of blacks in the West remained at only a few thousand throughout

the 19th century. Blacks did participate in nearly all segments of Western

society but many lived in segregated communities. They served in expeditions

that mapped the West and as fur traders, miners, cowboys, Indian fighters,

scouts, woodsmen, farm hands, saloon workers, cooks, and outlaws. The famed

Buffalo Soldiers were members of the Negro regiments of the U.S. Army and

they played a substantial role in fighting the Plains Indians and the Apache

in Arizona. Relatively few freed slaves, known as "Exodusters", became

prairie settlers in all-black towns like Nicodemus, KS.

Bison versus cattle

The rise of the cattle industry and the cowboy is directly

tied to the demise of the huge bison herds of the Great Plains. Once numbering

over 25 million, bison were a vital resource animal for the Plains Indians,

providing food, hides for clothing and shelter, and bones for implements.

Drought, loss of habitat, disease, and over-hunting steadily reduced the

herds through the 19th century to the point of near extinction. Overland

trails and growing settlements began to block the free movement of the

herds to feeding and breeding areas. Initially, commercial hunters sought

bison to make "pemmican", a mixture of pounded buffalo meat, fat, and berries,

which was a long-lasting food used by trappers and other outdoorsmen. Not

only did white hunters impact the herds, but Indians who arrived from the

East also contributed to their reduction. Adding to the kill was the wanton

slaughter of bison by sportsmen, migrants, and soldiers. Shooting bison

from passing trains was common sport. However, the greatest negative effect

on the herds was the huge markets opened up by the completion of the transcontinental

railroad. Hides in great quantities were tanned into leather and fashioned

into clothing and furniture. Killing far exceeded market requirements,

reaching over one million per year. As many as five bison were killed for

each one that reached market, and most of the meat was left to rot on the

plains and at trackside after removal of the hides. Skulls were often ground

for fertilizer. A skilled hunter could kill over 100 bison in a day.

| By the 1870s, the great slaughter of bison had a major

impact on the Plains Indians, dependent on the animal both economically

and spiritually. Soldiers of the U.S. Army deliberately encouraged and

abetted the killing of bison as part of the campaigns against the Sioux

and Pawnee, in an effort to deprive them of their resource animal and to

demoralize them.

The sharp decline of the herds of the Plains created a

vacuum which was exploited by the growing cattle industry. Spanish cattlemen

had introduced cattle ranching and longhorn cattle to the Southwest in

the 17th century, and the men who worked the ranches, called "vaqueros",

were the first "cowboys" in the West. After the Civil War?with railheads

available at Abilene, Kansas City, Dodge City, and Wichita?Texas ranchers

raised large herds of longhorn cattle and drove them north along the Western,

Chisholm, and Shawnee trails. The cattle were slaughtered in Chicago, St.

Louis, and Kansas City. The Chisholm Trail, laid out by cattleman Joseph

McCoy along an old trail marked by Jesse Chisholm, was the major artery

of cattle commerce, carrying over 1.5 million head of cattle between 1867

and 1871 over the 800 miles (1,300 km) from south Texas to Abilene, Kansas.

The long drives were treacherous, especially crossing water such as the

Brazos and the Red River and when they had to fend off Indians and rustlers

looking to make off with their cattle. A typical drive would take three

to four months and contained two miles (3 km) of cattle six abreast. Despite

the risks, the long Texas drives proved very profitable and attracted investors

from the United States and abroad. The price of one head of cattle raised

in Texas was about $4 but was worth more than $40 back East. |

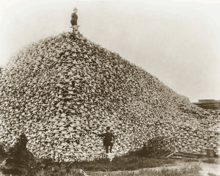

..

Photograph from the mid-1870s of a pile

of American bison skulls to be

ground into fertilizer. |

By the 1870s and 1880s, cattle ranches expanded further

north into new grazing grounds and replaced the bison herds in Wyoming,

Montana, Colorado, Nebraska and the Dakota territory, using the rails to

ship to both coasts. Many of the largest ranches were owned by Scottish

and English financiers. The single largest cattle ranch in the entire West

was owned by American John W. Iliff, "cattle king of the Plains", operating

in Colorado and Wyoming. Gradually, longhorns were replaced by the American

breeds of Hereford and Angus, introduced by settlers from the Northwest.

Though less hardy and more disease-prone, these breeds produced better

tasting beef and matured faster.

Then disaster struck the cattle industry. A terribly severe