| Prospecting on the San Bernardino National Forest

The Lure of Prospecting

Anyone who pans for gold hopes to be rewarded by the glitter

of colors in the fine material collected in the bottom of the pan. Although

the exercise and outdoor activity experienced in prospecting are rewarding,

there are few thrills comparable to finding gold. Even an assay report

showing an appreciable content of gold in a sample obtained from a lode

deposit is exciting. The would-be prospector hoping for financial gain,

however, should carefully consider all the pertinent facts before deciding

on a prospecting venture.

History and Background of Prospecting

In recent times, only a few prospectors among the many

thousands who searched the western part of the United States ever found

a valuable deposit. Most of the gold mining districts in the West were

located by pioneers, many of whom were experienced gold miners from the

southern Appalachian region, but even in colonial times only a small proportion

of the gold seekers were successful. Over the past several centuries the

country has been thoroughly searched by prospectors. During the depression

of the 1930's, prospectors searched the better known gold-producing areas

throughout the Nation, especially in the West, and the little-known areas

as well. The results of their activities have never been fully documented,

but incomplete records indicate that an extremely small percentage of the

total number of active prospectors supported themselves by gold mining.

Of the few significant discoveries reported, nearly all were made by prospectors

of long experience who were familiar with the regions in which they were

working.

Many believe that it is possible to make wages or better

by panning gold in the streams of the West, particularly in regions where

placer mining formerly flourished. However, most placer deposits have been

thoroughly reworked at least twice--first by Chinese laborers, who arrived

soon after the initial boom periods and recovered gold from the lower grade

deposits and tailings left by the first miners, and later by itinerant

miners during the 1930's. Geologists and engineers who systematically investigate

remote parts of the country find small placer diggings and old prospect

pits whose number and wide distribution imply few, if any, recognizable

surface indications of metal-bearing deposits were overlooked by the earlier

miners and prospectors.

Prospecting History in Big Bear

The Big Bear Back Country Place is known for its colorful

mining history, prehistoric habitations and scenic character. From 1860

until the early 1900s, Holcomb Valley was the location of southern California's

largest gold rush and the mining towns of Belleville, Clapboard Town and

Union Town were located here. Extractions of gold, silver and copper continued

here over a longer period of time than anywhere else in California. The

last mining operation of any size concluded in 1958. Holcomb Valley is

a California Historic District, noted for its abundant historic and prehistoric

sites. Other historic mining areas are present in Lone Valley and Rattlesnake

Canyon. Rose Mine, which housed a mountain community at the turn of the

century is now a National Historical Site.

Placer Deposits

A placer deposit is a concentration of a natural material

that has accumulated in unconsolidated sediments of a stream bed, beach,

or residual deposit. Gold derived by weathering or other process from lode

deposits is likely to accumulate in placer deposits because of its weight

and resistance to corrosion. In addition, its characteristically sun-yellow

color makes it easily and quickly recognizable even in very small quantities.

The gold pan or miner's pan is a shallow sheet-iron vessel with sloping

sides and flat bottom used to wash gold-bearing gravel or other material

containing heavy minerals. The process of washing material in a pan, referred

to as "panning," is the simplest and most commonly used and least expensive

method for a prospector to separate gold from the silt, sand, and gravel

of the stream deposits. It is a tedious, back-breaking job and only with

practice does one become proficient in the operation.

Many placer districts in California have been mined on

a large scale as recently as the mid-1950's. Streams draining the rich

Mother Lode region--the Feather, Mokelumne, American, Cosumnes, Calaveras,

and Yuba Rivers--and the Trinity River in northern California have concentrated

considerable quantities of gold in gravels. In addition, placers associated

with gravels that are stream remnants from an older erosion cycle occur

in the same general area.

In addition to these localities, placer gold occurs along

many of the intermittent and ephemeral streams of arid regions in Nevada,

Arizona, New Mexico, and southern California. In many of these places a

large reserve of low-grade placer gold may exist, but the lack of a permanent

water supply for conventional placer mining operations requires the use

of expensive dry or semidry concentrating methods to recover the gold.

Modern Day Prospecting

Today's prospector must determine where prospecting is

permitted and be aware of the regulations under which he is allowed to

search for gold and other metals. Permission to enter upon privately owned

land must be obtained from the land owner. Determination of land ownership

and location and contact with the owner can be a time-consuming chore but

one which has to be done before prospecting can begin.

Determination of the location and extent of public lands

open to mineral entry for prospecting and mining purposes also is a time

consuming but necessary requirement. National parks, for example, are closed

to prospecting. Certain lands under the jurisdiction of the Forest Service

and the Bureau of Land Management may be entered for prospecting, but sets

of rules and regulations govern entry. The following statement from a pamphlet

issued in 1978 by the U.S. Department of the Interior and entitled "Staking

a mining claim on Federal Lands" responds to the question "Where May I

Prospect?"

There are still areas where you may prospect, and if a

discovery of a valuable, locatable mineral is made, you may stake a claim.

These areas are mainly in Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado,

Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New

Mexico, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Such areas are mainly unreserved, unappropriated Federal public lands administered

by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) of the U.S. Department of the Interior

and in national forests administered by the Forest Service of the U.S.

Department of Agriculture. Public land records in the proper BLM State

Office will show you which lands are closed to mineral entry under the

mining laws. These offices keep up-to-date land status plats that are available

to the public for inspection. BLM is publishing a series of surface and

mineral ownership maps that depict the general ownership pattern of public

lands. These maps may be purchased at most BLM Offices. For a specific

tract of land, it is advisable to check the official land records at the

proper BLM State Office.

What are the rules for prospecting for gold and staking

claims in the National Forest?

* Prospecting, mining and claim staking

activities are permitted on National Forest system unappropriated land.

Claimants have an express and implied right to access their claims when

permitted under Forest Service surface use regulations (36 CFR;228). Check

with the Bureau of Land Management Office for land status pertaining to

mining claims and the Ranger Station for land appropriation status.

* An Administrative Pass is a temporary

authorization issued at no charge for prospectors and miners who have a

statutory right to enter and prospect on public lands sanctioned under

the General Mining Act of 1872, as amended.

* Other visitors using the forest for

recreation are required to purchase an Adventure Pass for a fee, which

is required to park their vehicles while recreating in 'High Impact Recreation

Areas' (HIRA).

* An Administrative pass may be issued

for a 14 day period for members of a mining club and other prospectors

at no charge. If they require a longer period, we request them to submit

a Notice of Intent for the District Ranger's review to determine if the

proposed activity causes a significant surface disturbance. If the proposed

activity does not cause a significant surface disturbance, then the District

Ranger may issue an Administrative Pass for up to one year at no cost.

* The Notice of Intent requires your

name, address, telephone number, a claim map or the approximate location

of the proposed activity, the number of samples, the depth of the sample

site, the beneficiation method and need for water.

* If the District Ranger determines

that if the proposed activity may cause a significant surface disturbance,

the claimant, prospector and the mining clubs will be required to submit

a Plan of Operation. This will require substantive information about the

mining, beneficiation, reclamation methods and a substantial reclamation

performance bond will be required.

* Prospecting does not require a mining

claim or an exact location of the activity, an approximate location will

suffice.

* A Notice of Intent is required

if the proposed activity is located in an environmentally sensitive area

(1-e, Holcomb Valley, Lytle Creek, Horse Thief Canyon, Cactus Flats, Santa

Ana wash and Rose Mine). This includes panning for gold, dry washing, high

banking, metal detecting and suction dredging. Call the Ranger Station

if you are not sure about the sensitivity of the area involving the proposed

activity. Members of mining clubs are encouraged to follow this procedure.

* There are several hundred abandoned

mines on the forest. The public is prohibited from entering any of these

openings. If any of these of openings are causing a clear and present danger

to the public, report the location to the local Ranger Station for signing

or fencing.

* To stake a mining claim, you need

to follow Bureau of Land Management guidelines as they are the lead agency

for minerals management. The Forest Service administers the surface use

regulations in accordance with the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 36,

part 228.

* Mining claimants are not allowed

to drive off National Forest Designated Routes to access their claims.

They are required to have an approved Plan of Operation from the District

Ranger for access.

For the Use of Metal Detectors on the National Forest

The allowable use of metal detectors on National Forest

system lands takes a number of different forms. Detectors are used in searching

for treasure trove, locating historical and pre historical artifacts and

features,

prospecting for minerals, and searching for recent coins and lost metal

objects. Of these four types of uses for metal detectors, the first three

are covered by existing regulations that require special authorization,

i.e. special use permits, notice of intent, or plan of operation.

The search for treasure trove, which is defined as money,

un mounted gems, or precious metals in the form of coin, plate, or bullion

that has been deliberately hidden with the intention of recovering it later,

is an activity which is regulated by the Forest Service. Searching for

treasure trove has the potential of causing considerable disturbance and

damage to resources and thus requires a Special Use Permit from the US

Forest Service. Methods utilized in searching for treasure trove must be

specified in the permits issued. Permits may not be granted in each and

every case, but applications will be reviewed with attention being paid

to the justification given and guarantees for the restoration of any damage

that might occur to other resources. The use of metal detectors in searching

for treasure trove is permissible when under this type of permit, but must

be kept within the conditions of the permit.

The use of a metal detector to locate objects of historic

or archaeological value is permissible subject to the provisions of the

Antiquities Act of 1906, the Archaeological Resources Preservation Act

1979, and the Secretary of Agriculture's regulations. Such use requires

a Special Use Permit covering the exploration, excavation. appropriation,

or removal of historic and archaeological materials and information. Such

permits are available for legitimate historical and pre historical research

activities by qualified individuals. Unauthorized use of metal detectors

in the search for and collection of historic and archaeological artifacts

is a violation of existing regulations and statutes.

The use of a metal detector to locate mineral deposits

such as gold, and silver on National Forest System lands is considered

prospecting and is subject to the provisions of the General Mining Law

of 1872.

Searching for coins of recent vintage (less than 50 years)

and small objects having no historical value, as a recreational pursuit,

using a hand-held metal detector, does not currently require a Special

Use Permit as long as the use of the equipment is confined to areas which

do not posses historic or prehistoric resources.

Important Mining & Recreational Tips

* Pick/shovel excavations may

only be done in conjunction with gold panning and metal detecting and must

be made below the high water mark of the stream channel. All excavations

must be filled in before leaving the area. Prospectors in the Holcomb

Valley and Lytle Creek areas need to submit a "Notice of Intent" to the

local Ranger Station.

* Do not cut trees, limbs or

brush, do not dig up ground cover or dig under tree roots.

* Pack out everything you brought

into the area, especially trash.

* Do not wash yourself or your dishes

in the creeks. All wash water is to be contained and disposed of, off of

National Forest Land

* Bury human waste 4 to 6 inches deep

and at least 100 feet from the stream channel.

* Vehicles must remain on designated

routes, unless approved by the District Ranger.

* Check local conditions and

fire restrictions by calling the local Ranger Station.

Minerals Program Manager

San Bernardino National Forest

602 S. Tippecanoe Avenue

San Bernardino, CA 92408

Phone 909-382-2898

|

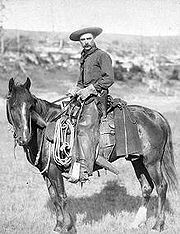

| Cowboy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches

in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude

of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late

19th century became a figure of special significance and legend. A subtype,

called a wrangler, specifically tends the horses used to work cattle. In

addition to ranch work, some cowboys work for or participate in rodeos.

Cowgirls, first defined as such in the late 19th century, had a less-well

documented historical role, but in the modern world have established the

ability to work at virtually identical tasks and obtained considerable

respect for their achievements. There are also cattle handlers in many

other parts of the world, particularly South America and Australia, who

perform work similar to the cowboy in their respective nations.

The cowboy has deep historic roots tracing back to Spain

and the earliest settlers of the Americas. Over the centuries, differences

in terrain, climate and the influence of cattle-handling traditions from

multiple cultures created several distinct styles of equipment, clothing

and animal handling. As the ever-practical cowboy adapted to the modern

world, the cowboy's equipment and techniques also adapted to some degree,

though many classic traditions are still preserved today.

Etymology and usage

The English word cowboy has an origin from several earlier

terms that referred to both age and to cattle or cattle-tending work.

The word "cowboy" appeared in the English language by

1725. It appears to be a direct English translation of vaquero, a Spanish

word for an individual who managed cattle while mounted on horseback. It

was derived from vaca, meaning "cow." This Spanish word has a long history,

developed from the Latin word vacca. Another English word for a cowboy,

buckaroo, is an Anglicization of vaquero. At least one linguist has speculated

that the word "buckaroo" derives from the Arabic word bakara or bakhara,

also meaning "heifer" or "young cow", and may have entered Spanish during

the centuries of Islamic rule.

Originally, the term may have been intended literally

- "a boy who tends cows" - but had developed its modern sense as an adult

cattle handler of the American west by 1849. Variations on the word "cowboy"

appeared later. "Cowhand" appeared in 1852, and "cowpoke" in 1881, originally

restricted to the individuals who prodded cattle onto railroad cars with

long poles. Names for a cowboy in American English now include buckaroo,

cowpoke, cowhand, and cowpuncher. "Cowboy" is a term common throughout

the west and particularly in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, "Buckaroo"

is used primarily in the Great Basin and California, and "cowpuncher" mostly

in Texas and surrounding states.

The word cowboy also had English language roots beyond

simply being a translation from Spanish. Originally, the English word "cowherd"

was used to describe a cattle herder, (similar to "shepherd," a sheep herder)

and often referred to a preadolescent or early adolescent boy, who usually

worked on foot. (Equestrianism required skills and an investment in horses

and equipment rarely available to or entrusted to a child, though in some

cultures boys rode a donkey while going to and from pasture) This word

is very old in the English language, originating prior to the year 1000.[10]

In Antiquity, herding of sheep, cattle and goats was often the job of minors,

and still is a task for young people in various third world cultures.

Because of the time and physical ability needed to develop

necessary skills, the cowboy often did began his career as an adolescent,

earning wages as soon as he had enough skill to be hired, (often as young

as 12 or 13) and who, if not crippled by injury, might handle cattle or

horses for the rest of his working life. In the United States, a few women

also took on the tasks of ranching and learned the necessary skills, though

the "cowgirl" (discussed below) did not become widely recognized or acknowledged

until the close of the 19th century. On western ranches today, the working

cowboy is usually an adult. Responsibility for herding cattle or other

livestock is no longer considered a job suitable for children or early

adolescents. However, both boys and girls growing up in a ranch environment

often learn to ride horses and perform basic ranch skills as soon as they

are physically able, usually under adult supervision. Such youths, by their

late teens, are often given responsibilities for "cowboy" work on the ranch,

and ably perform work that requires a level of maturity and levelheadedness

that is not generally expected of their urban peers.

History

| The origins of the cowboy tradition come from Spain,

beginning with the hacienda system of medieval Spain. This style of cattle

ranching spread throughout much of the Iberian peninsula and later, was

imported to the Americas. Both regions possessed a dry climate with sparse

grass, and thus large herds of cattle required vast amounts of land in

order to obtain sufficient forage. The need to cover distances greater

than a person on foot could manage gave rise to the development of the

horseback-mounted vaquero. Various aspects of the Spanish equestrian tradition

can be traced back to Arabic rule in Spain, including Moorish elements

such as the use of Oriental-type horses, the la jineta riding style characterized

by a shorter stirrup, solid-treed saddle and use of spurs, the heavy noseband

or hackamore, (Arabic šak?ma, Spanish jaquima) and other horse-related

equipment and techniques. Certain aspects of the Arabic tradition, such

as the hackamore, can in turn be traced to roots in ancient Persia.

During the 16th century, the Conquistadors and other Spanish

settlers brought their cattle-raising traditions as well as both horses

and domesticated cattle to the Americas, starting with their arrival in

what today is Mexico and Florida. The traditions of Spain were transformed

by the geographic, environmental and cultural circumstances of New Spain,

which later became Mexico and the Southwestern United States. In turn,

the land and people of the Americas also saw dramatic changes due to Spanish

influence. |

|

Thus, though popularly considered as a North American

icon, the traditional cowboy began with a Hispanic tradition, which evolved

further in what today is Mexico and the Southwestern United States into

the vaquero of northern Mexico and the charro of the Jalisco and Michoacán

regions. Most vaqueros were men of mestizo and Native American origin while

most of the hacendados (ranch owners) were ethnically Spanish. Mexican

traditions spread both South and North, influencing equestrian traditions

from Argentina to Canada.

The arrival of horses was particularly significant, as

equines had been extinct in the Americas since the end of the prehistoric

ice age. However, horses quickly multiplied in America and became crucial

to the success of the Spanish and later settlers from other nations. The

earliest horses were originally of Andalusian, Barb and Arabian ancestry,

but a number of uniquely American horse breeds developed in North and South

America through selective breeding and by natural selection of animals

that escaped to the wild. The Mustang and other colonial horse breeds are

now called "wild," but in reality are feral horses — descendants of domesticated

animals.

As English-speaking traders and settlers expanded westward,

English and Spanish traditions, language and culture merged to some degree.

Before the Mexican-American War in 1848, New England merchants who traveled

by ship to California encountered both hacendados and vaqueros, trading

manufactured goods for the hides and tallow produced from vast cattle ranches.

American traders along what later became known as the Santa Fe Trail had

similar contacts with vaquero life. Starting with these early encounters,

the lifestyle and language of the vaquero began a transformation which

merged with English cultural traditions and produced what became known

in American culture as the "cowboy".

With the arrival of railroads, and an increased demand

for beef in the wake of the American Civil War, the iconic American cowboy

evolved as the older traditions combined with the need to drive cattle

from the ranches where they were raised to the nearest railheads, often

hundreds of miles away.

Ethnicity of the traditional cowboy

| American cowboys were drawn from multiple sources. By

the late 1860s, following the American Civil War and the expansion of the

cattle industry, former soldiers from both the Union and Confederacy came

west, seeking work, as did large numbers of restless white men in general.

A significant number of African-American ex-slaves also were drawn to cowboy

life, in part because there was not quite as much discrimination in the

west as in other areas of American society at the time. A significant number

of Mexicans and American Indians already living in the region also worked

as cowboys.

Many early vaqueros were Indian people trained to work

for the Spanish missions in caring for the mission herds. Later, particularly

after 1890, when American policy promoted "assimilation" of Indian people,

some Indian boarding schools also taught ranching skills. Today, some Native

Americans in the western United States own cattle and small ranches, and

many are still employed as cowboys, especially on ranches located near

Indian Reservations. The "Indian Cowboy" also became a commonplace sight

on the rodeo circuit. |

Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho youths learning to

brand cattle at the Seger Indian School,

Oklahoma Territory, ca. 1900. |

Because cowboys ranked low in the social structure of

the period, there are no firm figures on the actual proportion of various

races. One writer states that cowboys were "… of two classes—those recruited

from Texas and other States on the eastern slope; and Mexicans, from the

south-western region. …" Census records suggest that about 15% of all cowboys

were of African-American ancestry—ranging from about 25% on the trail drives

out of Texas, to very few in the northwest. Similarly, cowboys of Mexican

descent also averaged about 15% of the total, but were more common in Texas

and the southwest.

Regardless of ethnicity, most cowboys came from lower

social classes and the pay was poor. The average cowboy earned approximately

a dollar a day, plus food, and, when near the home ranch, a bed in the

bunkhouse, usually a barracks-like building with a single open room.

Roundups

Large numbers of cattle lived in a semi-feral, or semi-wild

state on the open range and were left to graze, mostly untended, for much

of the year. In many cases, different ranchers formed "associations" and

grazed their cattle together on the same range. In order to determine the

ownership of individual animals, they were marked with a distinctive brand,

applied with a hot iron, usually while the cattle were still young calves.

The primary cattle breed seen on the open range was the Longhorn, descended

from the original Spanish Longhorns imported in the 16th century, though

by the late 19th century, other breeds of cattle were also brought west,

including the meatier Hereford, and often were crossbred with Longhorns.

In order to find young calves for branding, and to sort

out mature animals intended for sale, ranchers would hold a roundup, usually

in the spring. A roundup required a number of specialized skills on the

part of both cowboys and horses. Individuals who separated cattle from

the herd required the highest level of skill and rode specially trained

"cutting" horses, trained to follow the movements of cattle, capable of

stopping and turning faster than other horses. Once cattle were sorted,

most cowboys were required to rope young calves and restrain them to be

branded and (in the case of most bull calves) castrated. Occasionally it

was also necessary to restrain older cattle for branding or other treatment.

A large number of horses were needed for a roundup. Each

cowboy would require three to four fresh horses in the course of a day's

work. Horses themselves were also rounded up. It was common practice in

the west for young foals to be born of tame mares, but allowed to grow

up "wild" in a semi-feral state on the open range. There were also "wild"

herds, often known as mustangs. Both types were rounded up, and the mature

animals tamed, a process called horse breaking, or "bronco-busting," (var.

"bronc busting") usually performed by cowboys who specialized in training

horses. In some cases, extremely brutal methods were used to tame horses,

and such animals tended to never be completely reliable. However, other

cowboys became aware of the need to treat animals in a more humane fashion

and modified their horse training methods, often re-learning techniques

used by the vaqueros, particularly those of the Californio tradition. Horses

trained in a gentler fashion were more reliable and useful for a wider

variety of tasks.

Informal competition arose between cowboys seeking to

test their cattle and horse-handling skills against one another, and thus,

from the necessary tasks of the working cowboy, the sport of rodeo developed.

Cattle drives

Prior to the mid-19th century, most ranchers primarily

raised cattle for their own needs and to sell surplus meat and hides locally.

There was also a limited market for hides, horns, hooves, and tallow in

assorted manufacturing processes. Nationally, prior to 1865, there was

little demand for beef. At the end of the American Civil War, however,

Philip Danforth Armour opened a meat packing plant in Chicago, which became

known as Armour and Company, and with the expansion of the meat packing

industry, the demand for beef increased significantly. By 1866, cattle

could be sold to northern markets for as much as $40 per head, making it

potentially profitable for cattle, particularly from Texas, to be herded

long distances to market.

The first large-scale effort to drive cattle from Texas

to the nearest railhead for shipment to Chicago occurred in 1866, when

many Texas ranchers banded together to drive their cattle to the closest

point that railroad tracks reached, which at that time was in Sedalia,

Missouri. However, farmers in eastern Kansas, afraid that Longhorns would

transmit cattle fever to local animals as well as trample crops, formed

groups that threatened to beat or shoot cattlemen found on their lands.

Therefore, the 1866 drive failed to reach the railroad, and the cattle

herds were sold for low prices. However, in 1867, a cattle shipping facility

was built west of farm country around the railhead at Abilene, Kansas,

and became a center of cattle shipping, loading over 36,000 head of cattle

that year. The route from Texas to Abilene became known as the Chisholm

Trail, after Jesse Chisholm, who marked out the route. It ran through present-day

Oklahoma, which then was Indian Territory. However, in spite of Hollywood

portrayals of the west, there were relatively few conflicts with Native

Americans, who usually allowed cattle herds to pass through for a toll

of ten cents a head. Later, other trails forked off to different railheads,

including those at Dodge City and Wichita, Kansas. By 1877, the largest

of the cattle-shipping boom towns, Dodge City, Kansas, shipped out 500,000

head of cattle.

Cattle drives had to strike a balance between speed and

the weight of the cattle. While cattle could be driven as far as 25 miles

in a single day, they would lose so much weight that they would be hard

to sell when they reached the end of the trail. Usually they were taken

shorter distances each day, allowed periods to rest and graze both at midday

and at night. On average, a herd could maintain a healthy weight moving

about 15 miles per day. Such a pace meant that it would take as long as

two months to travel from a home ranch to a railhead. The Chisholm trail,

for example, was 1,000 miles long.

On average, a single herd of cattle on a drive numbered

about 3,000 head. To herd the cattle, a crew of at least 10 cowboys was

needed, with three horses per cowboy. Cowboys worked in shifts to watch

the cattle 24 hours a day, herding them in the proper direction in the

daytime and watching them at night to prevent stampedes and deter theft.

The crew also included a cook, who drove a chuck wagon, usually pulled

by oxen, and a horse wrangler to take charge of the remuda, or herd of

spare horses. The wrangler on a cattle drive was often a very young cowboy

or one of lower social status, but the cook was a particularly well-respected

member of the crew, as not only was he in charge of the food, he also was

in charge of medical supplies and had a working knowledge of practical

medicine.

By the 1880s, the expansion of the cattle industry resulted

the need for additional open range. Thus many ranchers expanded into the

northwest, where there were still large tracts of unsettled grassland.

Texas cattle were herded north, into the Rocky Mountain west and the Dakotas.

The cowboy adapted much of his gear to the colder conditions, and westward

movement of the industry also led to intermingling of numerous regional

traditions from California to Texas, often with the cowboy taking the most

useful elements of each.

End of the open range.

Barbed wire, an innovation of the 1880s, allowed cattle

to be confined to designated areas to prevent overgrazing of the range.

In Texas and surrounding areas, increased population required ranchers

to fence off their individual lands. In the north, overgrazing stressed

the open range, leading to insufficient winter forage for the cattle and

starvation, particularly during the harsh winter of 1886–1887, when hundreds

of thousands of cattle died across the Northwest, leading to collapse of

the cattle industry. By the 1890s, barbed wire fencing was also standard

in the northern plains, railroads had expanded to cover most of the nation,

and meat packing plants were built closer to major ranching areas, making

long cattle drives from Texas to the railheads in Kansas unnecessary. Hence,

the age of the open range was gone and large cattle drives were over. Smaller

cattle drives continued at least into the 1940s, as ranchers, prior to

the development of the modern cattle truck, still needed to herd cattle

to local railheads for transport to stockyards and packing plants. Meanwhile,

ranches multiplied all over the developing West, keeping cowboy employment

high, if still low-paid, but also somewhat more settled.

Social world

Over time, the cowboys of the American West developed

a personal culture of their own, a blend of frontier and Victorian values

that even retained vestiges of chivalry. Such hazardous work in isolated

conditions also bred a tradition of self-dependence and individualism,

with great value put on personal honesty, exemplified in songs and poetry.

However, some men were also drawn to the frontier because

they were attracted to men. Other times, in a region where men significantly

outnumbered women, even social events normally attended by both sexes were

at times all male, and men could be found partnering up with one another

for dances. Homosexual acts between young, unmarried men occurred, but

cowboys culture itself was and remains deeply homophobic. Though anti-sodomy

laws were common in the Old West, they often were only selectively enforced.

Development of the modern cowboy image

The traditions of the working cowboy were further etched

into the minds of the general public with the development of Wild West

Shows in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which showcased and romanticized

the life of both cowboys and Native Americans. Beginning in the 1920s and

continuing to the present day, Western movies popularized the cowboy lifestyle

but also formed persistent stereotypes, both positive and negative. In

some cases, the cowboy and the violent gunslinger are often associated

with one another. On the other hand, some actors who portrayed cowboys

promoted positive values, such as the "cowboy code" of Gene Autry, that

encouraged honorable behavior, respect and patriotism.

Likewise, cowboys in movies were often shown fighting

with American Indians. However, the reality was that, while cowboys were

armed against both predators and human thieves, and often used their guns

to run off people of any race who attempted to steal, or rustle cattle,

nearly all actual armed conflicts occurred between Indian people and cavalry

units of the U.S. Army.

In reality, working ranch hands past and present had very

little time for anything other than the constant, hard work involved in

maintaining a ranch.

Cowgirls

The history of women in the west, and women who worked

on cattle ranches in particular, is not as well documented as that of men.

However, institutions such as the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame

have made significant efforts in recent years to gather and document the

contributions of women.

There are few records mentioning girls or women working

to drive cattle up the cattle trails of the Old West. However women did

considerable ranch work, and in some cases (especially when the men went

to war or on long cattle drives) ran them. There is little doubt that women,

particularly the wives and daughters of men who owned small ranches and

could not afford to hire large numbers of outside laborers, worked side

by side with men and thus needed to ride horses and be able to perform

related tasks. The largely undocumented contributions of women to the west

were acknowledged in law; the western states led the United States in granting

women the right to vote, beginning with Wyoming in 1869. Early photographers

such as Evelyn Cameron documented the life of working ranch women and cowgirls

during the late 19th and early 20th century.

While impractical for everyday work, the sidesaddle was

a tool that gave women the ability to ride horses in "respectable" public

settings instead of being left on foot or confined to horse-drawn vehicles.

Following the Civil War, Charles Goodnight modified the traditional English

sidesaddle, creating a western-styled design. The traditional charras of

Mexico preserve a similar tradition and ride sidesaddles today in charreada

exhibitions on both sides of the border.

It wasn't until the advent of Wild West Shows that "cowgirls"

came into their own. These adult women were skilled performers, demonstrating

riding, expert marksmanship, and trick roping that entertained audiences

around the world. Women such as Annie Oakley became household names. By

1900, skirts split for riding astride became popular, and allowed women

to compete with the men without scandalizing Victorian Era audiences by

wearing men's clothing or, worse yet, bloomers. In the movies that followed

from the early 20th century on, cowgirls expanded their roles in the popular

culture and movie designers developed attractive clothing suitable for

riding Western saddles. |

Fannie Sperry Steele,

Champion Lady Bucking Horse Rider,

Winnipeg Stampede, 1913

Modern western-style show attire for women,

inspired by cowgirl regalia |

Independently of the entertainment industry, the growth

of rodeo brought about another type of cowgirl—the rodeo cowgirl. In the

early Wild West shows and rodeos, women competed in all events, sometimes

against other women, sometimes with the men. Cowgirls such as Fannie Sperry

Steele rode the same "rough stock" and took the same risks as the men (and

all while wearing a heavy split skirt that was still more encumbering than

men's trousers) and competed at major rodeos such as the Calgary Stampede

and Cheyenne Frontier Days.

Rodeo competition for women changed after 1925 when Eastern

promoters started staging indoor rodeos in places like Madison Square Garden.

Women were generally excluded from the men's events and many of the women's

events were dropped. In today's rodeos, men and women compete equally together

only in the event of team roping, though technically women today could

enter other open events. There also are all-women rodeos where women compete

in bronc riding, bull riding and all other traditional rodeo events. However,

in open rodeos, cowgirls primarily compete in the timed riding events such

as barrel racing, and most professional rodeos do not offer as many women's

events as men's events.

Boys and girls are more apt to compete against one another

in all events in high-school rodeos as well as O-Mok-See competition, where

even boys can be seen in traditionally "women's" events such as barrel

racing. Outside of the rodeo world, women compete equally with men in nearly

all other equestrian events, including the Olympics, and western riding

events such as cutting, reining, and endurance riding.

Today's working cowgirls generally use clothing, tools

and equipment indistinguishable from that of men, other than in color and

design, usually preferring a flashier look in competition. Sidesaddles

are only seen in exhibitions and a limited number of specialty horse show

classes. A cowgirl wears jeans, close-fitting shirts, boots, hat, and when

needed, chaps and gloves. If working on the ranch, they perform the same

chores as cowboys and dress to suit the situation.

Regional traditions within the United States

Geography, climate and cultural traditions caused differences

to develop in cattle-handling methods and equipment from one part of the

United States to another. In the modern world, remnants of two major and

distinct cowboy traditions remain, known today as the "Texas" tradition

and the "Spanish", "Vaquero", or "California" tradition. Less well-known

but equally distinct traditions also developed in Hawaii and Florida. Today,

the various regional cowboy traditions have merged to some extent, though

a few regional differences in equipment and riding style still remain,

and some individuals choose to deliberately preserve the more time-consuming

but highly skilled techniques of the pure vaquero or "buckaroo" tradition.

The popular "horse whisperer" style of natural horsemanship was originally

developed by practitioners who were predominantly from California and the

Northwestern states, clearly combining the attitudes and philosophy of

the California vaquero with the equipment and outward look of the Texas

cowboy.

Texas tradition

In the early 1800s, the Spanish Crown, and later, independent

Mexico, offered empresario grants in what would later be Texas to non-citizens,

such as settlers from the United States. In 1821, Stephen F. Austin and

his East Coast comrades became the first Anglo-Saxon community speaking

Spanish. Following Texas independence in 1836, even more Americans immigrated

into the empresario ranching areas of Texas. Here the settlers were strongly

influenced by the Mexican vaquero culture, borrowing vocabulary and attire

from their counterparts, but also retaining some of the livestock-handling

traditions and culture of the Eastern United States and Great Britain.

The Texas cowboy was typically a bachelor who hired on with different outfits

from season to season.

Following the American Civil War, vaquero culture diffused

eastward and northward, combining with the cow herding traditions of the

eastern United States that evolved as settlers moved west. Other influences

developed out of Texas as cattle trails were created to meet up with the

railroad lines of Kansas and Nebraska, in addition to expanding ranching

opportunities in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain Front, east of the

Continental Divide.

Thus, the Texas cowboy tradition arose from a combination

of cultural influences, in addition to the need for adaptation to the geography

and climate of west Texas and the need to conduct long cattle drives to

get animals to market.

California tradition

The vaquero, the Spanish or Mexican cowboy who worked

with young, untrained horses, arrived in the 1700s and flourished in California

and bordering territories during the Spanish Colonial period. Settlers

from the United States did not enter California until after the Mexican-American

War, and most early settlers were miners rather than livestock ranchers,

leaving livestock-raising largely to the Spanish and Mexican people who

chose to remain in California. The California vaquero or buckaroo, unlike

the Texas cowboy, was considered a highly-skilled worker, who usually stayed

on the same ranch where he was born or had grown up and raised his own

family there. In addition, the geography and climate of much of California

was dramatically different from that of Texas, allowing more intensive

grazing with less open range, plus cattle in California were marketed primarily

at a regional level, without the need (nor, until much later, even the

logistical possibility) to be driven hundreds of miles to railroad lines.

Thus, a horse- and livestock-handling culture remained in California and

the Pacific Northwest that retained a stronger direct Spanish influence

than that of Texas.

Cowboys of this tradition were dubbed buckaroos by English-speaking

settlers. The term officially appeared in American English in 1889 and

is believed to have originated as an anglicized version of vaquero, though

there is a folk etymology that the term derived from "bucking", a behavior

seen in some young or fresh horses. The words "buckaroo" and Vaquero are

still used on occasion in the Great Basin, parts of California and, less

often, in the Pacific Northwest.

Florida Cowhunter or "Cracker cowboy"

| The Florida "cowhunter" or "cracker cowboy" of the 19th

and early 20th centuries was distinct from the Texas and California traditions.

Florida cowboys did not use lassos to herd or capture cattle. Their primary

tools were bullwhips and dogs. Florida cattle and horses were small. The

"cracker cow", also known as the "native cow", or "scrub cow" averaged

about 600 pounds, had large horns and large feet.

Since the Florida cowhunter didn't need a saddle horn

for anchoring a lariat, many did not use Western saddles, instead using

a McClellan saddle. While some individuals wore boots that reached above

the knees for protection from snakes, others wore brogans. They usually

wore inexpensive wool or straw hats, and used ponchos for protection from

rain.

Cattle and horses were introduced into Florida late in

the 16th century. Throughout the 17th century, cattle ranches owned by

Spanish officials and missions operated in northern Florida to supply the

Spanish garrison in St. Augustine and markets in Cuba. These ranches brought

in some vaqueros from Spain, but many of the workers were Timucua Indians.

Diseases and Spanish suppression of rebellions severely reduced the Timucua

population. By the beginning of the 18th century, raids by soldiers from

the Province of Carolina and their Indian allies reduced the Timucuas to

a remnant and ended the Spanish ranching era. |

A cracker cowboy

artist: Frederick Remington. |

In the 18th century, Creek, Seminole, and other Indian people

moved into the former Timucua areas and started herding the cattle left

from the Spanish ranches. In the 19th century, most tribes in the area

were dispossessed of their land and cattle and pushed south or west by

white settlers and the United States government. By the middle of the 19th

century white ranchers were running large herds of cattle on the extensive

open range of central and southern Florida. The hides and meat from Florida

cattle became such a critical supply item for the Confederacy during the

American Civil War that a "Cow Cavalry" was organized to round up and protect

the herds from Union raiders. After the Civil War, Florida cattle were

periodically driven to ports on the Gulf of Mexico and shipped to market

in Cuba.

Hawaiian Paniolo

The Hawaiian cowboy, the paniolo, is also a direct descendant

of the vaquero of California and Mexico. Experts in Hawaiian etymology

believe "Paniolo" is a Hawaiianized pronunciation of español. (The

Hawaiian language has no /s/ sound, and all syllables and words must end

in a vowel.) Paniolo, like cowboys on the mainland of North America, learned

their skills from Mexican vaqueros.

By the early 1800s, Capt. George Vancouver's gift of cattle

to Pai`ea Kamehameha, monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, had multiplied astonishingly,

and were wreaking havoc throughout the countryside. About 1812, John Parker,

a sailor who had jumped ship and settled in the islands, received permission

from Kamehameha to capture the wild cattle and develop a beef industry.

The Hawaiian style of ranching originally included capturing

wild cattle by driving them into pits dug in the forest floor. Once tamed

somewhat by hunger and thirst, they were hauled out up a steep ramp, and

tied by their horns to the horns of a tame, older steer (or ox) that knew

where the paddock with food and water was located. The industry grew slowly

under the reign of Kamehameha's son Liholiho (Kamehameha II).

Later, Liholiho's brother, Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III),

visited California, then still a part of Mexico. He was impressed with

the skill of the Mexican vaqueros, and invited several to Hawai`i in 1832

to teach the Hawaiian people how to work cattle.

Even today, traditional paniolo dress, as well as certain

styles of Hawaiian formal attire, reflect the Spanish heritage of the vaquero.

The traditional Hawaiian saddle, the noho lio, and many other tools of

the cowboy's trade have a distinctly Mexican/Spanish look and many Hawaiian

ranching families still carry the names of the vaqueros who married Hawaiian

women and made Hawai`i their home.

Other

Montauk, New York, on Long Island makes a somewhat debatable

claim of having the oldest cattle operation in what today is the United

States, having run cattle in the area since European settlers purchased

land from the Indian people of the area in 1643. Although there were substantial

numbers of cattle on Long Island, as well as the need to herd them to and

from common grazing lands on a seasonal basis, no consistent "cowboy" tradition

developed amongst the cattle handlers of Long Island, who actually lived

with their families in houses built on the pasture grounds. The only actual

"cattle drives" held on Long Island consisted of one drive in 1776, when

the Island's cattle were moved in a failed attempt to prevent them from

being captured by the British during the American Revolution, and three

or four drives in the late 1930s, when area cattle were herded down Montauk

Highway to pasture ground near Deep Hollow Ranch.

Today, the "Salt Water Cowboys" are known for rounding

up the feral Chincoteague Ponies from Assateague Island and driving them

across Assateague Channel into pens on Chincoteague Island, Virginia during

the annual Pony Penning.

Cowboys in Canada

Ranching in Canada has traditionally been dominated by

one province, Alberta. The most successful early settlers of the province

were the ranchers, who found Alberta's foothills to be ideal for raising

cattle. Most of Alberta's ranchers were English settlers, but cowboys such

as John Ware — who brought the first cattle into the province in 1876 —

were American. American style open range dryland ranching began to dominate

southern Alberta (and, to a lesser extent, southwestern Saskatchewan) by

the 1880s. The nearby city of Calgary became the centre of the Canadian

cattle industry, earning it the nickname "Cowtown". The cattle industry

is still extremely important to Alberta, and cattle outnumber people in

the province. While cattle ranches defined by barbed wire fences replaced

the open range just as they did in the US, the cowboy influence lives on.

Canada's first rodeo, the Raymond Stampede, was established in 1902. In

1912, the Calgary Stampede began, and today it is the world’s richest cash

rodeo. Each year, Calgary’s northern rival Edmonton, Alberta stages the

Canadian Finals Rodeo, and dozens of regional rodeos are held through the

province.

Cowboys outside North America

In addition to the original Mexican vaquero, the Mexican

charro, the North American cowboy, and the Hawaiian paniolo, the Spanish

also exported their horsemanship and knowledge of cattle ranching to the

gaucho of Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and (with the spelling gaúcho)

southern Brazil, the chalan in Peru, the llanero of Venezuela, and the

huaso of Chile.

In Australia, which has a large ranch (station) culture,

cowboys are known as stockmen and drovers (with trainee stockmen referred

to as jackaroos and jillaroos). The Spanish tradition also influenced Australia,

both via concepts adapted from the Americas, and traditions brought directly

from Spain, each of which arrived along with imports of various breeds

of horses, cattle, sheep and other livestock[citation needed].

The idea of horseback riders who guard herds of cattle,

sheep or horses is common wherever wide, open land for grazing exists.

In the French Camargue, riders called "gardians" herd cattle. In Hungary,

csikós guard horses and gulyás tend to cattle. The herders

in the region of Maremma, in Tuscany (Italy) are called butteros. The Asturian

pastoral population is referred to as Vaqueiros de alzada.

Modern working cowboys

On the ranch, the cowboy is responsible for feeding the

livestock, branding and earmarking cattle (horses also are branded on many

ranches), plus tending to animal injuries and other needs. The working

cowboy usually is in charge of a small group or "string" of horses and

is required to routinely patrol the rangeland in all weather conditions

checking for damaged fences, evidence of predation, water problems, and

any other issue of concern.

They also move the livestock to different pasture locations,

or herd them into corrals and onto trucks for transport. In addition, cowboys

may do many other jobs, depending on the size of the "outfit" or ranch,

the terrain, and the number of livestock. On a smaller ranch with fewer

cowboys—often just family members, cowboys are generalists who perform

many all-around tasks; they repair fences, maintain ranch equipment, and

perform other odd jobs. On a very large ranch (a "big outfit"), with many

employees, cowboys are able to specialize on tasks solely related to cattle

and horses. Cowboys who train horses often specialize in this task only,

and some may "Break" or train young horses for more than one ranch.

The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics collects

no figures for cowboys, so the exact number of working cowboys is unknown.

Cowboys are included in the 2003 category, Support activities for animal

production, which totals 9,730 workers averaging $19,340 per annum. In

addition to cowboys working on ranches, in stockyards, and as staff or

competitors at rodeos, the category includes farmhands working with other

types of livestock (sheep, goats, hogs, chickens, etc.). Of those 9,730

workers, 3,290 are listed in the subcategory of Spectator sports which

includes rodeos, circuses, and theaters needing livestock handlers.

Attire

Most cowboy attire, sometimes termed Western wear, grew

out of practical need and the environment in which the cowboy worked. Most

items were adapted from the Mexican vaqueros, though sources from other

cultures, including Native Americans and Mountain Men contributed.

* Cowboy hat; High crowned hat with

a wide brim to protect from sun, overhanging brush, and the elements. There

are many styles, initially influenced by John B. Stetson's Boss of the

plains, which was designed in response to the climatic conditions of the

West.

* Bandanna; a large cotton neckerchief

that had a myriad of uses from mopping up sweat to masking the face from

dust storms. In modern times, is now more likely to be a silk neckscarf

for decoration and warmth.

* Cowboy boots; a boot with a high

top to protect the lower legs, pointed toes to help guide the foot into

the stirrup, and high heels to keep the foot from slipping through the

stirrup while working in the saddle; with or without detachable spurs.

* Chaps (usually pronounced "shaps")

or chinks protect the rider's legs while on horseback, especially riding

through heavy brush or during rough work with livestock.

* Jeans or other sturdy, close-fitting

trousers made of canvas or denim, designed to protect the legs and prevent

the trouser legs from snagging on brush, equipment or other hazards. Properly

made cowboy jeans also have a smooth inside seam to prevent blistering

the inner thigh and knee while on horseback.

* Gloves, usually of deerskin or other

leather that is soft and flexible for working purposes, yet provides protection

when handling barbed wire, assorted tools or clearing native brush and

vegetation.

Many of these items show marked regional variations. Parameters

such as hat brim width, or chap length and material were adjusted to accommodate

the various environmental conditions encountered by working cowboys.

Tools

* Lariat; from the Spanish "la riata,"

meaning "the rope," sometimes called a lasso, especially in the East, or

simply, a "rope". This is a tightly twisted stiff rope, originally of rawhide

or leather, now often of nylon, made with a small loop at one end called

a "hondo." When the rope is run through the hondo, it creates a loop that

slides easily, tightens quickly and can be thrown to catch animals.

* Spurs; metal devices attached to

the heel of the boot, featuring a small metal shank, usually with a small

serrated wheel attached, used to allow the rider to provide a stronger

(or sometimes, more precise) leg cue to the horse.

* Firearms: Modern cowboys often have

access to a rifle, used to protect the livestock from predation by wild

animals, more often carried inside a pickup truck than on horseback, though

rifle scabbards are manufactured, and allow a rifle to be carried on a

saddle. A pistol is more often carried when on horseback. The modern ranch

hand often uses a .22 caliber "varmit" rifle for modern ranch hazards,

such as rattlesnakes, coyotes, and rabid skunks. In areas near wilderness,

a ranch cowboy may carry a higher-caliber rifle to fend off larger predators

such as mountain lions. In contrast, the cowboy of the 1880s usually carried

a heavy caliber revolver such as the single action .44-40 or .45 Colt Peacemaker

(the civilian version of the 1872 Single Action Army). The working cowboy

of the 1880s rarely carried a long arm, as they could get in the way when

working cattle, plus they added extra weight. However, many cowboys owned

rifles, and often used them for market hunting in the off season. Though

many models were used, Cowboys who were part-time market hunters preferred

rifles that could take the widely available .45-70 "Government" ammunition,

such as certain Sharps, Remington, Springfield models, as well as the Winchester

1876. However, by far the single most popular long arms were the lever-action

repeating Winchesters, particularly lighter models such as the Model 1873

chambered for the same .44/40 ammunition as the Colt, allowing the cowboy

to carry only one kind of ammunition.

* Knife; cowboys have traditionally

favored some form of pocket knife, specifically the folding cattle knife

or stock knife. The knife has multiple blades, usually including a leather

punch and a "sheepsfoot" blade.

* Other weapons; while the modern American

cowboy came to existence after the invention of gunpowder, cattle herders

of earlier times were sometimes equipped with heavy polearms, bows or lances.

Horses

The traditional means of transport for the cowboy, even

in the modern era, is by horseback. Horses can travel over terrain that

vehicles cannot access. Horses, along with mules and burros, also serve

as pack animals. The most important horse on the ranch is the everyday

working ranch horse that can perform a wide variety of tasks; horses trained

to specialize exclusively in one set of skills such as roping or cutting

are very rarely used on ranches. Because the rider often needs to keep

one hand free while working cattle, the horse must neck rein and have good

cow sense—it must instinctively know how to anticipate and react to cattle.

A good stock horse is on the small side, generally under

15.2 hands (62 inches) tall at the withers and often under 1000 pounds,

with a short back, sturdy legs and strong muscling, particularly in the

hindquarters. While a steer roping horse may need to be larger and weigh

more in order to hold a heavy adult cow, bull or steer on a rope, a smaller,

quick horse is needed for herding activities such as cutting or calf roping.

The horse has to be intelligent, calm under pressure and have a certain

degree of 'cow sense" -- the ability to anticipate the movement and behavior

of cattle.

Many breeds of horse make good stock horses, but the most

common today in North America is the American Quarter Horse, which is a

horse breed developed primarily in Texas from a combination of Thoroughbred

bloodstock crossed on horses of Mustang and other Iberian horse ancestry,

with influences from the Arabian horse and horses developed on the east

coast, such as the Morgan horse and now-extinct breeds such as the Chickasaw

and Virginia Quarter-Miler.

Horse equipment or tack

Equipment used to ride a horse is referred to as tack

and includes:

* Western saddle; a saddle specially

designed to allow horse and rider to work for many hours and to provide

security to the rider in rough terrain or when moving quickly in response

to the behavior of the livestock being herded. A western saddle has a deep

seat with high pommel and cantle that provides a secure seat. Deep, wide

stirrups provide comfort and security for the foot. A strong, wide saddle

tree of wood, covered in rawhide (or made of a modern synthetic material)

distributes the weight of the rider across a greater area of the horse's

back, reducing the pounds carried per square inch and allowing the horse

to be ridden longer without harm. A horn sits low in front of the rider,

to which a lariat can be snubbed, and assorted dee rings and leather "saddle

strings" allow additional equipment to be tied to the saddle.

* Saddle blanket; a blanket or pad

is required under the Western saddle to provide comfort and protection

for the horse.

* Saddle bags (leather or nylon) can

be mounted to the saddle, behind the cantle, to carry various sundry items

and extra supplies. Additional bags may be attached to the front or the

saddle.

* Bridle; a Western bridle usually

has a curb bit and long split reins to control the horse in many different

situations. Generally the bridle is open-faced, without a noseband, unless

the horse is ridden with a tiedown. Young ranch horses learning basic tasks

usually are ridden in a jointed, loose-ring snaffle bit, often with a running

martingale. In some areas, especially where the "California" style of the

vaquero or buckaroo tradition is still strong, young horses are often seen

in a bosal style hackamore.

* Martingales of various are seen on

horses that are in training or have behavior problems.

Vehicles

The most common motorized vehicle driven in modern ranch

work is the pickup truck. Sturdy and roomy, with a high ground clearance,

and often four-wheel drive capability, it has an open box, called a "bed,"

and can haul supplies from town or over rough trails on the ranch. It is

used to pull stock trailers transporting cattle and livestock from one

area to another and to market. With a horse trailer attached, it carries

horses to distant areas where they may be needed. Motorcycles are sometimes

used instead of horses for some tasks, but the most common smaller vehicle

is the four-wheeler. It will carry a single cowboy quickly around the ranch

for small chores. In areas with heavy snowfall, snowmobiles are also common.

However, in spite of modern mechanization, there remain jobs, particularly

those involving working cattle in rough terrain or in close quarters, that

are best done by cowboys on horseback.

Rodeo cowboys

The word rodeo is from the Spanish rodear (to turn), which

means roundup. In the beginning there was no difference between the working

cowboy and the rodeo cowboy, and in fact, the term working cowboy did not

come into use until the 1950s. Prior to that it was assumed that all cowboys

were working cowboys. Early cowboys both worked on ranches and displayed

their skills at the roundups.

The advent of professional rodeos allowed cowboys, like

many athletes, to earn a living by performing their skills before an audience.

Rodeos also provided employment for many working cowboys who were needed

to handle livestock. Many rodeo cowboys are also working cowboys and most

have working cowboy experience.

The dress of the rodeo cowboy is not very different from

that of the working cowboy on his way to town. Snaps, used in lieu of buttons

on the cowboy's shirt, allowed the cowboy to escape from a shirt snagged

by the horns of steer or bull. Styles were often adapted from the early

movie industry for the rodeo. Some rodeo competitors, particularly women,

add sequins, colors, silver and long fringes to their clothing in both

a nod to tradition and showmanship. Modern riders in "rough stock" events

such as saddle bronc or bull riding may add safety equipment such as kevlar

vests or a neck brace, but use of safety helmets in lieu of the cowboy

hat is yet to be accepted, in spite of constant risk of injury.

American Revolution

The term "cowboy" was used during the American Revolution

to describe American fighters who opposed the movement for independence.

Claudius Smith, an outlaw identified with the Loyalist cause, was referred

to as the "Cow-boy of the Ramapos" due to his penchant for stealing oxen,

cattle and horses from colonists and giving them to the British. In the

same period, a number of guerilla bands operated in Westchester County,

which marked the dividing line between the British and American forces.

These groups were made up of local farmhands who would ambush convoys and

carry out raids on both sides. There were two separate groups: the "skinners"

fought for the pro-independence side; the "cowboys" supported the British.

Popular culture

As the frontier ended, the cowboy life came to be highly

romanticized. Exhibitions such as those of Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West

Show helped to popularize the image of the cowboy as an idealized representative

of the tradition of chivalry.

In today's society, there is little understanding of the

daily realities of actual agricultural life. Cowboys are more often associated

with (mostly fictitious) Indian-fighting than with their actual life of

ranch work and cattle-tending. Actors such as John Wayne are thought of

as exemplifying a cowboy ideal, even though western movies seldom bear

much resemblance to real cowboy life. Arguably, the modern rodeo competitor

is much closer to being an actual cowboy, as many were actually raised

on ranches and around livestock, and the rest have needed to learn livestock-handling

skills on the job.

However, in the United States and the Canadian West, as

well as Australia, guest ranches offer people the opportunity to ride horses

and get a taste of the western life—albeit in far greater comfort. Some

ranches also offer vacationers the opportunity to actually perform cowboy

tasks by participating in cattle drives or accompanying wagon trains. This

type of vacation was popularized by the 1991 movie City Slickers, starring

Billy Crystal.

The cowboy is also portrayed as a masculine ideal via

images ranging from the Marlboro Man to the Village People.

Symbolism

The long history of the West in popular culture tends

to define those clothed in Western clothing as cowboys or cowgirls whether

they have ever been on a horse or not. This is especially true when applied

to entertainers and those in the public arena who wear western wear as

part of their persona.

However, many people, particularly in the West, wear elements

of Western clothing, particularly cowboy boots or hats, as a matter of

form even though they have other jobs, up to and including lawyers, bankers,

and other white collar professionals. Conversely, some people raised on

ranches do not necessarily define themselves cowboys or cowgirls unless

they feel their primary job is to work with livestock or if they compete

in rodeos.

Actual cowboys have derisive expressions for individuals

who adopt cowboy mannerisms as a fashion pose without any actual understanding

of the culture. For example, a "drugstore cowboy" means someone who wears

the clothing but cannot actually ride anything but the stool of the drugstore

soda fountain--or, in modern times, a bar stool. The phrase, "all hat and

no cattle," is used to describe someone (usually male) who boasts about

himself, far in excess of any actual accomplishments. The word "dude" (or

the now-archaic term "greenhorn") indicates an individual unfamiliar with

cowboy culture, especially one who is trying to pretend otherwise.

Outside of the United States, the cowboy became an archetypal

symbol of American individualism. In the late 1950s, a Congolese youth

subculture calling themselves the Bills based their style and outlook on

Hollywood's depiction of cowboys in movies. Something similar occurred

with the term "Apache," which in early twentieth century Parisian society

was a slang term for an outlaw.

Negative associations

The word "cowboy" is also used in a negative sense. Originally

this derived from the behavior of some cowboys in the boomtowns of Kansas,

at the end of the trail for long cattle drives, where cowboys developed

a reputation for violence and wild behavior due to the inevitable impact

of large numbers of cowboys, mostly young single men, receiving their pay

in large lump sums upon arriving in communities with many drinking and

gambling establishments.

"Cowboy" as an adjective for "reckless" developed in the

1920s. "Cowboy" is sometimes used today in a derogatory sense to describe

someone who is reckless or ignores potential risks, irresponsible or who

heedlessly handles a sensitive or dangerous task.[84] TIME Magazine referred

to President George W. Bush's foreign policy as "Cowboy diplomacy," and

Bush has been described in the press, particularly in Europe, as a "cowboy".

In the British Isles, Australia and New Zealand, "cowboy"

is used as an adjective when applied to tradesmen whose work is of shoddy

and questionable value, e.g., "a cowboy plumber". Similar usage is seen

in the United States to describe someone in the skilled trades who operates

without proper training or licenses. In the eastern United States, "cowboy"

as a noun is sometimes used to describe a fast or careless driver on the

highway.

|