Kit Carson from Wikipedia,

the free encyclopedia

|

Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson was an American frontiersman.

Early life

Born in Madison County, Kentucky near the city of Richmond,

Carson was raised in a rural area near Franklin, Missouri, where his family

moved in 1811 when he was about one year old. Carson's father, Lindsey

Carson, was a farmer of Scots-Irish descent, who had fought in the Revolutionary

War under General Wade Hampton. There were a total of 15 Carson children:

five by Lindsey Carson's first wife, and ten by Kit's mother, Rebecca Robinson.

Kit was the eleventh child in the family. The Carson family settled on

a tract of land owned by the sons of Daniel Boone, who had purchased the

land from the Spanish prior to the Louisiana Purchase. The Boone and Carson

families became good friends, working, socializing, and intermarrying. |

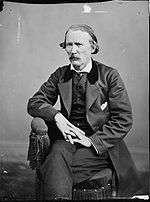

Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson

December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868 (aged 58) |

Carson was eight years old when his father was killed by

a falling tree while clearing land. Lindsey Carson's death reduced the

Carson family to a desperate poverty, forcing young Kit to drop out of

school to work on the family farm, as well as engage in hunting. At age

14, Kit was apprenticed to a saddlemaker (Workman's Saddleshop) in the

settlement of Franklin, Missouri. Franklin was situated at the eastern

end of the Santa Fe Trail, which had opened two years earlier. Many of

the clientele at the saddleshop were trappers and traders, from whom Kit

would hear their stirring tales of the Far West. Carson is reported to

have found work in the saddle shop suffocating: he once stated "the business

did not suit me, and I concluded to leave".

At sixteen, Carson secretly signed on with a large merchant

caravan heading to Santa Fe; his job was to tend the horses, mules, and

oxen. During the winter of 1826-1827 he stayed with Matthew Kinkead, a

trapper and explorer, in Taos, New Mexico, then known as the capital of

the fur trade in the Southwest. Kinkead had been a friend of Carson's father

in Missouri, and he taught Carson the skills of a trapper. Carson also

began learning the necessary languages and became fluent in Spanish, Navajo,

Apache, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Paiute, Shoshone, and Ute.

The trapper years (1829-40)

After gaining experience along the Santa Fe Trail and

in Mexico, Carson signed on with a trapping party of forty men, led by

Ewing Young in the Spring of 1829; this was Carson's first official expedition

as a trapper. The journey took the band into unexplored Apache country

along the Gila River. Ewing's group was approached and attacked by Apache

Indians. It was during this encounter that Carson shot and killed one of

the attacking Indians, the first time he killed a man.

At the age of 25, in the summer of 1835, Carson attended

an annual mountain man rendezvous, which was held along the Green River

in southwestern Wyoming. He became interested in an Arapaho woman whose

name, Waa-Nibe, is approximated in English as "Singing Grass" Her tribe

was camped nearby the rendezvous. Singing Grass is said to have been popular

at the rendezvous and also to have caught the attention of a French-Canadian

trapper, Joseph Chouinard. When Singing Grass chose Carson over Chouinard,

the rejected suitor became belligerent. Chouinard is reported to have disrupted

the camp, so that Carson could no longer tolerate the situation. Words

were exchanged, and Carson and Chouinard charged each other on horses,

brandishing their weapons. Carson blew off the thumb of his opponent with

his pistol, while Chouinard's rifle shot barely missed, grazing Carson

below his left ear and scorching his eye and hair. Carson stated that had

his opponent's horse not shied as he fired, Chouinard might have finished

him off, as he was a splendid shot.

Controversy regarding Chouinard's fate continues, with

no certainty achieved. The duel with Chouinard is said to have made Carson

famous among the mountain men but was also considered uncharacteristic

of him.

Carson considered his years as a trapper to be "the happiest

days of my life." Accompanied by Singing Grass, he worked with the Hudson's

Bay Company, as well as the renowned frontiersman Jim Bridger, trapping

beaver along the Yellowstone, Powder, and Big Horn Rivers, and was found

throughout what is now Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana. Carson's

first child, a daughter named Adeline, was born in 1837. Singing Grass

gave birth to a second daughter and developed a fever shortly after the

child's birth, and died sometime between 1838-40.

At this time, the nation was undergoing a severe depression

(see Panic of 1837). The fur industry was undermined by changing fashion

styles: a new demand for silk hats replaced the demand for beaver fur.

Also, the trapping industry had devastated the beaver population; this

combination of facts ended the need for trappers. Carson stated, "Beaver

was getting scarce, it became necessary to try our hand at something else."

He attended the last mountain man rendezvous, held in

the summer of 1840 (again at Ft. Bridger near the Green River) and moved

on to Bent's Fort, finding employment as a hunter. Carson married a Cheyenne

woman, Making-Our-Road, in 1841 but Making-Our-Road left him only a short

time later to follow her tribe's migration. By 1842 he met and became engaged

to the daughter of a prominent Taos family: Josefa Jaramillo. After receiving

instruction from Padre Antonio José Martínez, he was baptized

into the Catholic Church in 1842. When he was 34, he married 14-year-old

Josefa, his third wife, on February 6, 1843. They raised eight children,

the descendants of whom remain in the Arkansas Valley of Colorado.

Guide with Frémont (1842-1846)

Carson decided early in 1842 to return east to bring his

daughter Adeline to live with relatives near Carson's former home of Franklin,

for the purpose of providing her with an education. That summer he met

John C. Frémont on a Missouri River steamboat in Missouri. Frémont

was preparing to lead his first expedition and was looking for a guide

to take him to South Pass. The two men made acquaintance, and Carson offered

his services, as he had spent much time in the area. The five month journey,

made with 25 men, was a success, and Fremont's report was published by

Congress. His report "touched off a wave of wagon caravans filled with

hopeful emigrants" heading West.

Frémont's success in the first expedition lead

to his second expedition, undertaken in the summer of 1843, which proposed

to map and describe the second half of the Oregon Trail, from South Pass

to the Columbia River. Due to his proven skill as a guide in the first

expedition, Carson's services were again requested. This journey took them

along the Great Salt Lake into Oregon, establishing all the land in the

Great Basin to be land-locked, which contributed greatly to the understanding

of North American geography at the time. Their trip brought them into sight

of Mount Rainier, Mount Saint Helens, and Mount Hood.

One purpose of this expedition had been to locate the

Buenaventura, a major east-west river that was believed to connect the

Great Lakes with the Pacific Ocean. Though its existence was accepted as

scientific fact at the time, it was not to be found. Frémont's second

expedition established that this mystical river was a fable.

The second expedition became snowbound in the Sierra Nevadas

that winter, and was in danger of mass starvation. Carson's wilderness

expertise pulled them through, in spite of being half-starved. Food was

scarce enough that their mules "ate one another's tails and the leather

of the pack saddles."

The expedition moved south into the Mojave Desert, enduring

attacks by Natives, which killed one man. Also, when the expedition had

crossed into California, they had officially invaded Mexico. The threat

of military intervention by that country sent Fremont's expedition further

southeast, into Nevada, at a watering hole known as Las Vegas. The party

traveled on to Bent's Fort, and by August, 1844 returned to Washington,

over a year after their departure. Another Congressional report on Fremont's

expedition was published. By the time of the second report in 1845, Frémont

and Carson were becoming nationally famous.

Somewhere along this route, Frémont and party came

across a Mexican man and a boy who were survivors of an ambush by a band

of Natives, who had killed two men, staked two women to the ground and

mutilated them, and stolen 30 horses. Carson and fellow mountain man Alex

Godey took pity on the two survivors. They tracked the Native band for

2 days, and upon locating them, rushed into their encampment. They killed

two Native Americans, scattered the rest, and returned with the horses.

"More than any other single factor

or incident, [the Mojave Desert incident] from Frémont's second

expedition report is where the Kit Carson legend was born....."

On June 1, 1845 John Frémont and 55 men left St.

Louis, with Carson as guide, on the third expedition. The stated goal was

to "map the source of the Arkansas River", on the east side of the Rocky

Mountains. But upon reaching the Arkansas, Frémont suddenly made

a hasty trail straight to California, without explanation. Arriving in

the Sacramento Valley in early winter 1846, he promptly sought to stir

up patriotic enthusiasm among the American settlers there. He promised

that if war with Mexico started, his military force would "be there to

protect them." Frémont nearly provoked a battle with General José

Castro near Monterey, which would have likely resulted in the annihilation

of Frémont's group, due to the superior numbers of the Mexican troops.

Frémont then fled Mexican-controlled California, and went north

to Oregon, finding camp at Klamath Lake.

On the night of May 9, 1846 Frémont received a

courier, Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie, who brought him messages from

President James Polk. Frémont stayed up late reviewing these messages

and neglected to post a watchman for the camp, as was customary for security

measures. The neglect of this action is said to have been troubling to

Carson, yet he had "apprehended no danger". Later that night Carson was

awakened by the sound of a thump. Jumping up, he saw his friend and fellow

trapper Basil Lajeunesse sprawled in blood. He called an alarm and immediately

everyone else came to: they were under attack by Native Americans estimated

to be several dozen in number. By the time the assailants were beaten off,

two other members of Frémonts group were dead. The one dead warrior

was judged to be a Klamath Lake Native. Frémont's group fell into

"an angry gloom." Carson was beside himself, and Frémont reports

he smashed away at the dead warrior's face until it was pulp.

To avenge the deaths of his expedition members, Frémont

chose to attack a Klamath Tribe fishing village named Dokdokwas, at the

junction of the Williamson River and Klamath Lake, which took place May

10, 1846. Accounts by scholars vary as to what happened but it is certain

that the action completely destroyed the village. Carson was nearly killed

by a Klamath warrior later that day: his gun misfired, and the warrior

drew to shoot a poison arrow; but Frémont, seeing Carson's predicament,

trampled the warrior with his horse. Carson stated he felt that he owed

Frémont his life due to this incident.

"The tragedy of Dokdokwas is deepened

by the fact that most scholars now agree that Frémont and Carson,

in their blind vindictiveness, probably chose the wrong tribe to lash out

against: In all likelihood the band of Indians that had killed [Frémont's

three men] were from the neighboring Modocs....The Klamaths were culturally

related to the Modocs, but the two tribes were bitter enemies."

Turning south from Klamath Lake, Frémont led his

expedition back down the Sacramento Valley, and slyly promoted an insurrection

of American settlers, which he then took charge of once circumstances had

adequately developed, known as the Bear Flag Revolt. Events escalated when

a group of Mexicans murdered two American rebels. Frémont then intercepted

three Mexican men on June 28, 1846, crossing the San Francisco Bay, who

landed near San Quentin. Frémont ordered Carson to execute these

three men in revenge for the deaths of the two Americans.

Mexican American War service

Frémont's California Battalion next moved south

to the provincial capital of Monterey, California, and met Commodore Robert

Stockton there in mid-July 1846. Stockton had sailed into harbor with two

American warships and taken claim to Monterey for the United States. Learning

that the war with Mexico was underway, Stockton made plans to capture Los

Angeles and San Diego and proceed on to Mexico City. He joined forces with

Frémont, and made Carson a lieutenant, thus initiating Carson's

military career.

Frémont's unit arrived in San Diego on one of Stockton's

ships on July 29, 1846, and took over the town without resistance. Stockton,

traveling on a separate warship, claimed Santa Barbara a few days later.

(See Mission Santa Barbara and Presidio of Santa Barbara). Meeting up and

joining forces in San Diego, they marched to Los Angeles and claimed this

town without any challenge, and Stockton declared California to be United

States territory on August 17, 1846. The following day, August 18, Stephen

W. Kearny rode into Santa Fe, New Mexico with his Army of the West and

declared the New Mexican territory conquered.

Stockton and Frémont were eager to announce the

conquest of California to President Polk, and wished for Carson to carry

their correspondence overland to the President. Carson accepted the mission,

and pledged to cross the continent within 60 days. He left Los Angeles

with 15 men and 6 Delaware Indians on September 5.

Service with Kearny

Thirty one days later on October 6, Carson chanced to

meet Kearny and his 300 dragoons at the deserted village of Valverde.[19]

Kearny was under orders from the Polk Administration to subdue both New

Mexico and California, and set up governments there. Learning that California

was already conquered, he sent 200 of his men back to Santa Fe, and ordered

Carson to guide him back to California so he could stabilize the situation

there. Kearny sent the mail on to Washington by another courier.

For the next six weeks, Lt. Carson guided Kearny and the

100 dragoons west along the Gila River over very rugged terrain, arriving

at the Colorado River on November 25. On some parts of the trail mules

died at a rate of almost 12 a day. By December 5, three months after leaving

Los Angeles, Carson had brought Kearny's men to within 25 miles (40 km)

of their destination, San Diego.

A Mexican courier was captured en route to Sonora Mexico

carrying letters to General Jose Castro that reported a Mexican revolt

which had recaptured California from Commodore Stockton: all the coastal

cities now were back under Mexican control, except for San Diego, where

the Mexicans had Stockton pinned down and under siege. Kearny was himself

in perilous danger, as his force was reduced both in numbers and in a state

of physical exhaustion: they had to come out of the Gila River trail and

confront the Mexican forces, or risk perishing in the desert.

| The Battle of San Pasqual

While approaching San Diego, Kearny sent a rancher ahead

to notify Commodore Stockton of his presence. The rancher, Edward Stokes,

returned with 39 American troops and information that several hundred Mexican

dragoons under Capt Andres Pico were camped at the Indian village of San

Pasqual, lying on the route between him and Stockton. Kearny decided to

raid Pico in order to capture fresh horses, and sent out a scouting party

on the night of December 5-6.

The scouting party encountered a barking dog in San Pasqual,

and Captain Pico's troops were aroused from their sleep. Having been detected,

Kearny decided to attack, and organized his troops to advance on San Pasqual.

A complex battle evolved, where twenty-one Americans were killed and many

more wounded: many from the long lances of the Mexican caballeros, who

also displayed expert horsemanship. By the end of the second day, December

7, the Americans were nearly out of food and water, low on ammunition and

weak from the journey along the Gila River. They faced starvation and possible

annilation by the Mexican troops who vastly outnumbered them, and Kearny

ordered his men to dig in on top of a small hill.

Kearny then sent Carson and two other men to slip through

the siege and get reinforcements. Carson, Edward Beale, and an Indian left

on the night of December 8 for San Diego which was 25 miles (40 km) away.

Because their canteens made too much noise, they were left along the path.

Because their boots also made too much noise, Carson and Beale removed

these and tucked them under their belts. These they lost, and Carson and

Beale traveled the distance to San Diego barefoot through desert, rock,

and cactus.

|

Click on image to enlarge |

By December 10, Kearny had decided all hope was gone, and

planned to attempt a breakout the next morning: but that night, 200 American

troops on fresh horses arrived, the Mexican army dispersed with the new

show of strength. Kearny was able to arrive in San Diego by December 12.

This action contributed to the prompt reconquest of California by the American

forces.

Civil War and Indian campaigns

Following the recapture of Los Angeles in 1846, Frémont

was appointed Governor of California by Commodore Stockton. Frémont

sent Carson to carry messages back to Washington City. He stopped in St.

Louis and met with Senator Thomas Benton, who was a prominent supporter

of the settling of the West and a proponent of Manifest Destiny, and had

been prominent in getting Frémont's expedition reports published

by Congress. Once in Washington, Carson delivered his messages to Secretary

of State James Buchanan, as well as had meetings with Secretary of War

William Marcy and President James Polk.

Having completed this mission, Carson received orders

to do it all again: return to California with messages, receive further

messages there, and bring those back yet again to Washington. By the end

of the Frémont expeditions and these courier missions, Carson felt

he wanted to settle down with Joséfa, and decided in 1849 to go

into farming in Taos.

Carson's public image as an action hero had been sealed

by the Frémont expedition reports of 1845. In 1849, the first of

many Carson action novels appeared. The first, written by Charles Averill,

bore the name Kit Carson: The Prince of the Gold Hunters. This type of

western pulp fiction was known as "blood and thunders." In Averill's novel,

Carson finds a kidnapped girl and rescues her, after having vowed to her

distraught parents in Boston that he would scour the American West until

she was found.

This book was among the possessions Carson and Major William

Grier found when they recovered the body of Mrs. Ann White in November,

1849. Mrs. White and her daughter had been taken captive by Jicarilla Apaches

several weeks earlier. She had been traveling with her husband James White,

a trader, to Santa Fe, when a group of Indians approached them as they

camped along the Santa Fe trail. Mr. White tried to disperse the Indians

with his rifle, but they attacked, killing everyone except Mrs. White,

her daughter, and a servant.

Carson and Grier tracked the Indians for twelve days to

their camp on the Canadian River. Carson wanted an immediate attack, while

Grier wanted to parlay with the Jicarillas. The disagreement in tactics

caused delay, which gave the Indians time to disperse from camp and escape.

In the process, Mrs. White appears to have attempted to flee and was killed

by an arrow through the heart.

While picking through the belongings that the Jicarillas

had left in their camp, one of Major Grier's soldiers came across a book

that the White family had carried with them from Missouri: the paperback

novel starring Kit Carson. This book must have been shown to him, for he

was to comment on it later. This was the first time that the real Kit Carson

came in contact with his own myth.

The episode of the White massacre haunted Carson's memory

for many years. He once stated, "I have often thought that, as Mrs. White

read the book, she prayed for my appearance, knowing that I lived nearby."

His fear was that the book had given her a false hope. He wrote later,

"I have much regretted the failure to save the life of so esteemed a lady."

He was troubled by the implications and false image that developed around

his celebrity status.

When the American Civil War began in April 1861, Kit Carson

resigned his post as federal Indian agent for northern New Mexico and joined

the New Mexico volunteer infantry which was being organized by Ceran St.

Vrain. Although New Mexico Territory officially allowed slavery, geography

and economics made the institution so impractical that there were only

a handful of slaves within its boundaries. The territorial government and

the leaders of opinion all threw their support to the Union.

Overall command of Union forces in the Department of New

Mexico fell to Colonel Edward R. S. Canby of the Regular Army's 19th Infantry,

headquartered at Ft. Marcy in Santa Fe. Carson, with the rank of Colonel

of Volunteers, commanded the third of five columns in Canby's force. Carson's

command was divided into two battalions each made up of four companies

of the First New Mexico Volunteers, in all some 500 men.

Early in 1862, Confederate forces in Texas under General

Henry Hopkins Sibley undertook an invasion of New Mexico Territory. The

goal of this expedition was to conquer the rich Colorado gold fields and

redirect this valuable resource from the North to the South.

Advancing up the Rio Grande, Sibley's command clashed

with Canby's Union force at Valverde on February 21, 1862. The day-long

Battle of Valverde ended when the Confederates captured a Union battery

of six guns and forced the rest of Canby's troops back across the river

with losses of 68 killed and 160 wounded. Colonel Carson's column spent

the morning on the west side of the river out of the action, but at 1 p.m.,

Canby ordered them to cross, and Carson's battalions fought until ordered

to retreat. Carson lost one man killed and one wounded.

Colonel Canby had little or no confidence in the hastily

recruited, untrained New Mexico volunteers, "who would not obey orders

or obeyed them too late to be of any service." In his battle report, however,

he did commend Carson, among other volunteer officers, for his "zeal and

energy."

After the battle at Valverde, Colonel Canby and most of

the regular troops were ordered to the eastern front, but Carson and his

New Mexico Volunteers were fully occupied by "Indian troubles."

Prelude to the Navajo campaign

Contact between the Navajo and the U.S. Army was prompted

by a Navajo raid on Socorro, New Mexico near the end of September, 1846.

General Kearny, passing nearby on his way to California after his recent

conquest of Santa Fe, learned of the raid and sent a note to Col. William

Doniphan, his second in command in Santa Fe. He asked Doniphan to send

a regiment of soldiers into Navajo country and secure a peace treaty with

them.

A detachment of 30 men made contact with the Navajo and

spoke to the Navajo Chief Narbona in mid-October, about the same time that

Carson met Gen. Kearny on the trail to California. A second meeting with

Chief Narbona and Col. Doniphan occurred several weeks later. Doniphan

informed the Navajo that all their land now belonged to the United States,

and the Navajo and New Mexicans were now the "children of the United States."

In spite of this, the Navajo signed a treaty, known as the Bear Spring

treaty, on November 21, 1846. The treaty forbade the Navajo to raid or

make war on the New Mexicans, but allowed the New Mexicans the privilege

of making war on the Navajo if they saw fit.

Despite the treaty, raiding continued in New Mexico by

the Navajo, as well as the Jicarilla Apache, Mescalero Apache, Ute, Comanche,

and Kiowa. On August 16, 1849 the U.S. Army began an expedition into the

heart of Navajo country on an organized reconnaissance for the purpose

of impressing the Navajo with the might of the U.S. military, and to map

the terrain for further operations and to plan forts. The expedition was

led by Col. John Washington, the military governor of New Mexico at the

time. The expedition included nearly a thousand infantry (U.S. and New

Mexican volunteers), hundreds of horses and mules, a supply train, 55 Pueblo

Indian scouts, and four artillery guns.

On August 29-30, 1849, Washington's expedition was in

need of water, and began pillaging Navajo cornfields. It became clear the

Navajo intended to resist further pillaging, with mounted warriors darting

back and forth around Washington's troops. It is further documented that

Washington's reasoning was that the pillaging of Navajo crops was justified

because the Navajo would have to reimburse the U.S. government for the

cost of the expedition.

In this setting, Washington was still able to communicate

to the Navajo that in spite of the hostile situation, they and the whites

could "still be friends if the Navajo came with their chiefs the next day

and signed a treaty." This is in fact exactly what the Navajo did.

The next day Chief Narbona came once again to "talk peace,"

along with several other headmen. An accord was reached on nearly every

matter. When a New Mexican thought he saw his stolen horse and the Navajo

protested its return, a scuffle broke out. (The Navajo position was that

the horse had passed through several owners by this time, and now rightfully

belonged to its Navajo owner). Col. Washington sided with the New Mexican.

Since the Navajo owner now took his horse and fled the scene, Washington

told the New Mexican to go pick out any Navajo horse he wanted. The rest

of the Navajo present figured out what has happening, and turned and fled.

At this, Col. Washington ordered his soldiers to fire.

Seven Navajo were killed in the volleys; the rest ran

and could not be caught. One of the dying was Chief Narbona, who was scalped

as he lay dying by a New Mexican souvenir hunter. This massacre prompted

the warlike Navajo leaders such as Manuelito to gain influence over those

who were advocates of peace.

Carson's Navajo campaign

Raiding by Amerindians had been rather constant up through

1862, and New Mexicans were becoming more outspoken in their demand that

something be done. Col. Canby devised a plan for the removal of the Navajo

to a distant reservation and sent his plans to his superiors in Washington

D.C. But that year, Canby was promoted to general and recalled back east

for other duties. His replacement as commander of the Federal District

of New Mexico was Brigadier General James H. Carleton.

Carleton believed that the Navajo conflict was the reason

for New Mexico's "depressing backwardness." He naturally turned to Kit

Carson to help him fulfill his plans of upgrading New Mexico and his own

career: Carson was nationally known and had helped boost the careers of

a series of military commanders who had employed him.

Carleton saw a way to harness the anxieties that had been

stirred up [in New Mexico] by the Confederate invasion and the still-hovering

fear that the Texans might return. If the territory was already on a war

footing, the whole society alert and inflamed, then why not direct all

this ramped up energy toward something useful? Carleton immediately declared

a state of martial law, with curfews and mandatory passports for travel,

and then brought all his newly streamlined authority to bear on cleaning

up the Navajo mess. With a focus that bordered on obsession, he was determined

finally to make good on Kearny's old promise that the United States would

"correct all this."

Furthermore, Carleton believed there was gold in the Navajo's

country, and felt they should be driven out in order to allow the development

of this possibility. The immediate prelude to Carleton's Navajo campaign

was to force the Mescalero Apache to Bosque Redondo. Carleton ordered Carson

to kill all the men of that tribe, and say that he (Carson) had been sent

to "punish them for their treachery and crimes."

Carson was appalled by this brutal attitude and refused

to obey it. He accepted the surrender of more than a hundred Mescalero

warriors who sought refuge with him. Nonetheless, he completed his campaign

in a month.

When Carson learned that Carleton intended for him to

pursue the Navajo he sent Carleton a letter of resignation dated February

3, 1863. Carleton refused to accept this and used the force of his personality

to maintain Carson's cooperation. In language that was similar to his description

of the Mescalero Apache, Carleton ordered Carson to lead an expedition

against the Navajo, and to say to them, "You have deceived us too often,

and robbed and murdered our people too long, to trust you again at large

in your own country. This war shall be pursued against you if it takes

years, now that we have begun, until you cease to exist or move. There

can be no other talk on the subject."

Under Carleton's direction, Carson instituted a scorched

earth policy, burning Navajo fields, orchards and homes, and confiscating

or killing their livestock. He was aided by other Indian tribes with long-standing

enmity toward the Navajos, chiefly the Utes. Carson was pleased with the

work the Utes did for him, but they went home early in the campaign when

told they could not confiscate Navajo booty.

Carson also had difficulty with his New Mexico volunteers.

Troopers deserted and officers resigned. Carson urged Carleton to accept

two resignations he was forwarding, "as I do not wish to have any officer

in my command who is not contented or willing to put up with as much inconvenience

and privations for the success of the expedition as I undergo myself."

There were no pitched battles and only a few skirmishes

in the Navajo campaign. Carson rounded up and took prisoner every Navajo

he could find. In January 1864, Carson sent a company into Canyon de Chelly

to attack the last Navajo stronghold under the leadership of Manuelito.

The Navajo were forced to surrender because of the destruction of their

livestock and food supplies. In the spring of 1864, 8,000 Navajo men, women

and children were forced to march or ride in wagons 300 miles (480 km)

to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. Navajos call this "The Long Walk." Although

Carson had ridden home before the march began, he was held responsible

by the Navaho for breaking his word that those who surrendered would not

be harmed. As many as 300 died along the way,[citation needed] and many

more during the next four years of imprisonment. In 1868, after signing

a treaty with the U.S. government, remaining Navajos were allowed to return

to a reduced area of their homeland, where the Navajo Reservation exists

today. Thousands of other Navajo who had been living in the wilderness

returned to the Navajo homeland centered around Canyon de Chelly.

Southern Plains campaign

In November 1864, Carson was sent by General Carleton

to deal with the Natives in western Texas. Carson and his troopers met

a combined force of Kiowa, Comanche, and Cheyenne numbering over 1,500

at the ruins of Adobe Walls. In what is known as the Battle of Adobe Walls,

the Native force led by Dohäsan made several assaults on Carson's

forces which were supported by two mountain howitzers. Carson inflicted

heavy losses on the attacking warriors before burning the Indians' camp

and lodges and returning to Fort Bascom.

A few days later, Colonel John M. Chivington led U.S.

troops in a massacre at Sand Creek. Chivington boasted that he had surpassed

Carson and would soon be known as the great Indian killer. Carson was outraged

at the massacre and openly denounced Chivington's actions.

The Southern Plains campaign led the Comanches to sign

the Little Rock Treaty of 1865. In October 1865, General Carleton recommended

that Carson be awarded the brevet rank of brigadier-general, "for gallantry

in the battle of Valverde, and for distinguished conduct and gallantry

in the wars against the Mescalero Apaches and against the Navajo Indians

of New Mexico."

Colorado

When the Civil War ended, and with the Indian campaigns

successfully concluded, Carson left the army and took up ranching, finally

settling in Boggsville, Colorado (near the current Las Animas on the Purgatory

River).

Carson died at age 58 from an aortic aneurysm in the surgeon's

quarters in Fort Lyon, Colorado, located east of Las Animas. He is buried

in Taos, New Mexico, alongside his wife, Josefa ("Josephine"), who died

a month earlier of complications following child birth. His headstone inscription

reads: "Kit Carson / Died May 23, 1868 / Aged 59 Years."

Reputation

Many of the early images and recollections of Carson by

his peers and early writers portray him in a positive light. Albert Richardson,

who knew him personally in the 1850s, wrote that Kit Carson was "a gentleman

by instinct, upright, pure, and simple-hearted, beloved alike by Indians,

Mexicans, and Americans".

Oscar Lipps also presented a positive image of Carson:

"The name of Kit Carson is to this day held in reverence by all the old

members of the Navajo tribe. They say he knew how to be just and considerate

as well as how to fight the Indians".

Carson's contributions to western history have been reexamined

by historians, journalists and Native American activists since the 1960s.

In 1968, Carson biographer Harvey L. Carter stated:

In respect to his actual exploits and his actual character,

however, Carson was not overrated. If history has to single out one person

from among the Mountain Men to receive the admiration of later generations,

Carson is the best choice. He had far more of the good qualities and fewer

of the bad qualities than anyone else in that varied lot of individuals.

Some journalists and authors during the last 25 years

present a less benign view of Carson. Virginia Hopkins stated that "Kit

Carson was directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of thousands

of Indians". Her viewpoint is contrasted with that of Tom Dunlay, who wrote

in 2000 that Carson was directly responsible for less than fifty Indian

deaths and that, as Carson was not there at the time, Indian deaths on

the Long Walk or at Ft. Sumner were the responsibility of the United States

Army and General James Carleton.

Ed Quillen, publisher of Colorado Central magazine and

columnist for The Denver Post, wrote that "Carson...betrayed [the Navajo],

starved them by destroying their farms and livestock in Canyon de Chelly

and then brutally marched them to the Bosque Redondo concentration camp".

In 1970, Lawrence Kelly noted that Carleton had warned 18 Navajo chiefs

that all Navajo peoples "must come in and go to the Bosque Redondo where

they would be fed and protected until the war was over. That unless they

were willing to do this they would be considered hostile". Quillen's contention

that Bosque Redondo was a concentration camp has been challenged. For instance,

several men went off the reservation and stole 1,000 horses from the Comanche

Indians to the east. In addition, there was a hospital and a school, services

not available at a 'concentration camp' in the modern sense of the word,

particularly since World War II.

On January 19, 2006, Marley Shebala, senior news reporter

and photographer for Navajo Times, quoted the Fort Defiance Chapter of

the Navajo Nation as saying, "Carson ordered his soldiers to shoot any

Navajo, including women and children, on sight." Carson did not order his

soldiers to do that. This view of Carson's actions may be from General

James Carleton’s orders to Carson on October 12, 1862, concerning the Mescalero

Apaches: "All Indian men of that tribe are to be killed whenever and wherever

you can find them: the women and children will not be harmed, but you will

take them prisoners and feed them at Ft. Stanton until you receive other

instructions". Carson refused to obey that order then, and again with the

Navajo in 1863.[original research?]

Hampton Sides stated that Carson felt the Native Americans

needed reservations as a way of physically separating and shielding them

from white hostility and white culture. He believed most of the Indian

troubles in the West were caused by "aggressions on the part of whites."

He is said to have viewed the raids on white settlements as driven by desperation,

"committed from absolute necessity when in a starving condition." Native

American hunting grounds were disappearing as waves of white settlers filled

the region.

Popular culture

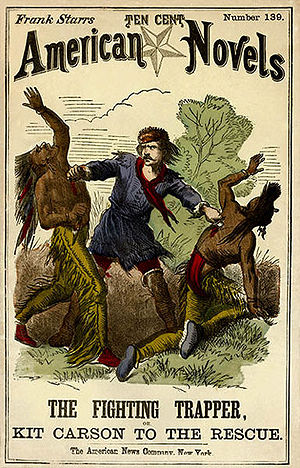

The legend of Kit Carson began before he died, and has

continued to grow through the years through dime novels, poems, music,

movies, television, and comic books. These fictional tales tend to portray

Carson as a heroic figure slaughtering two bears and a dozen Indians before

breakfast, and when mixed with a few real historic events, the result is

that Kit Carson becomes larger than life.

Click on image to enlarge |

Novels

There are at least 25 titles that have been recorded,

from Kit Carson, Prince of the Gold Hunters (1849) through Kit Carson,

King of Scouts (1923).

There is also a children's novel, Adaline Falling Star

(2000), by Mary Pope Osborne. It tells the story of Kit Carson and his

times through the eyes of his daughter from his first marriage.

Kit Carson also appears in historical fiction novel Flashman

and the Redskins by George MacDonald Fraser, where he helps guide Flashman

and his party across the west to California.

A character by the Name of Kit Carson also appears in

the Time Scout novels by Robert Asprin. While not identical in origin or

time period to the original, the character bears several similarities,

most notably the scouting profession.

There is a Welsh novel, I Ble Aeth Haul Y Bore by Eirug

Wyn, which focuses on the Great Walk, and Kit Carson is one of the main

characters. He first helps the Blue Coats to persuade the Navohos to move

from De Chelley, but then he realises his mistake and then helps them to

overcome a particularly evil Sargent called Dicks. |

Films

There were four silent films made with Kit Carson as the

"star" from 1903 to 1928. Hollywood produced 3 talking films: Fighting

with Kit Carson, a serial (1933), revised as a single movie: The Return

of Kit Carson (1947); Overland with Kit Carson (1939); and Kit Carson (1940),

starring Jon Hall in the title role. The Adventures of Kit Carson was a

TV series (1951-1955); Disney released Kit Carson and the Mountain Men

in 1977, Dream West was a TV 1986 docudrama that includes Kit Carson and

John C. Fremont as characters, and the History Channel produced "Carson

and Cody, the Hunter Heroes" in 2003. Several other motion pictures include

Kit Carson as a minor character.

Television

A successful western series,The Adventures of Kit Carson,

starring veteran actor Bill Williams ran on syndicated television from

1951-1955.A total of 104 half-hour episodes were filmed over 4 seasons.

Some of these are now available on DVD.

Music

The Canadian singer-songwriter, Bruce Cockburn, has a

track entitled "Kit Carson" on his 1991 album "Nothing But a Burning Light".

Comics

In 1931 Kit Carson was the subject of J. Carrol Mansfield's

daily comic strip High Lights of History and these strips were reprinted

as a Big Little Book, Kit Carson(1933). Avon began a series of Kit Carson

comic book that lasted 9 issues (1950-1955). Classics Illustrated No 112,

titled The Adventures of Kit Carson (1953), is based on John C. Abbott's

1873 book, and Blazing the Trails West, another Classics Illustrated publication,

includes a chapter on Kit Carson. Six Gun Heroes had two Kit Carson titles

(1957 & 1958) and there was a Kit Carson No. 10 in 1963. Boy's Life

includes a continuing strip story "Old Timere Tales of Kit Carson" from

March 1951 to May, 1953. There was a 1970 Walt Disney Comics Digest that

included Kit Carson, and Carson strips are in several issues of Frontier

Fighters and Indian Fighter. In England, there was a Kit Carson comic that

lasted at least 350 issues (1950s), and 7 Kit Carson Annuals (1954-1960)

Kit Carson is included in a number of 20th century novels

and pulp magazine stories: Comanche Chaser by Dane Coolidge, On Sweet Water

Trail by Sabra Conner, On to Oregon by H. W. Morrow, The Pioneers by C.

R. Cooper, The Long Trail by J. Allan Dunn and Peltry by H. D. H. Smith.

In Willa Cather's novel Death Comes for the Archbishop,

Kit Carson's multifaceted legend is explored, first as compassionate friend

to the Indians, later as "misguided" soldier.

In the Italian comic Tex Willer, Kit Carson appears as

Tex's sidekick.

|