| Volcanic Repeating Arms

From Wikipedia

The Volcanic Repeating Arms

Company was a company formed in 1852 by partners Horace Smith and Daniel

B. Wesson to develop Walter Hunt's Rocket Ball ammunition and lever action

mechanism. Volcanic made an improved version of the Rocket Ball ammunition,

and a carbine and pistol version of the lever action gun to fire it. While

the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company was short lived, it's descendants,

Smith & Wesson and Winchester Repeating Arms Company, became major

firearms manufacturers.

A Smith and Wesson Volcanic pistol,

circa 1855, in .31 caliber |

History

The original 1848 "Volition Repeating

Rifle" design by Hunt was revolutionary, introducing an early iteration

of the lever action repeating mechanism and the tubular magazine still

common today. However, Hunt's design was far from perfect, and only a couple

of prototypes were developed. Lewis Jennings patented an improved version

of Hunt's design in 1849, and versions of the Jenning's patent design were

built by Robbins & Lawrence Co. (under the direction of shop foreman

Benjamin Tyler Henry) and sold by C. P. Dixon until 1952, when financial

troubles ceased production.

The Jennings (top) and Volcanic

(bottom) rifles

In 1854, partners Horace Smith and

Daniel B. Wesson purchased the Jennings patent rights, and further improved

on the operating mechanism, developing the Volcanic pistol, and a new Volcanic

cartridge. Production resumed, still under the supervision of the Jenning's

foreman, B. Tyler Henry. The new cartridge improved upon the Hunt Rocket

Ball with the addition of a primer. Originally using the name "Smith &

Wesson Company", the name was changed to "Volcanic Repeating Arms Company"

in 1855, with the addition of new investors, the principle investor in

the new company being Oliver Winchester. The Volcanic Repeating Arms Company

purchased all rights for the Volcanic designs (both rifle and pistol versions

were in production by this time) from Smith and Wesson, who left the company

soon after, to found another "Smith & Wesson". The company was moved,

and in 1860 was reorganized as the New Haven Arms Company--still under

the supervision of foreman B. Tyler Henry. While continuing to make the

Volcanic rifle and pistol, Henry began to experiment with the new rimfire

ammunition, and modified the Volcanic lever action design to use it. The

result was the Henry rifle. By 1866, the company once again reorganized,

this time as the Winchester Repeating Arms company, and the name of Winchester

became synonymous with lever action rifles.

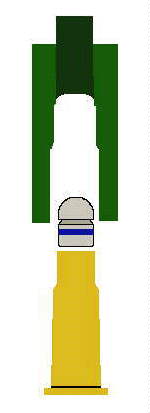

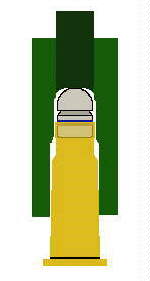

Top: A Jennings patent version of Walter Hunt's Volition

Rifle, which fired the Hunt Rocket Ball cartridge. Note percussion cap

hammer, as the Rocket Ball was externally primed. Bottom: A Volcanic Repeating

Arms Company lever action rifle, firing the improved, internally primed

Volcanic cartridge. The Henry Rifle uses the same design, adapted to rimfire

ammunition.

History of Rimfire Cartridges

From Wikipedia

The first rimfire cartridge was the .22 BB Cap, which

used no gunpowder by relying entirely on the priming compound for propulsion.

Dating back to 1857, the .22 BB Cap is essentially just a percussion cap

with a round ball pressed in the front, and a rim to hold it securely in

the chamber. Velocities are very low, comparable to an airgun, as the round

was intended for use in indoor shooting galleries. The next rimfire cartridge

was the .22 Short, developed for Smith and Wesson's first revolver; it

used a longer rimfire case and 4 grains (260 mg) of black powder to fire

a conical bullet. This led to the .22 Long, with a longer case and 5 grains

(320 mg) of black powder. The .22 Long Rifle is a .22 Long case loaded

with a longer, heavier bullet intended for better performance in the long

barrel of a rifle. The .22 Long Rifle is the most common cartridge in the

world. While larger rimfire calibers were made, such as the .41 Rimfire

Short, the .44 Henry Flat devised for the famous Henry Repeating Rifle,

up to the .58 Miller, the larger calibers were quickly replaced by centerfire

versions, and today the .22 caliber rimfires are all that survive of the

early rimfires. The early 21st century has seen a revival in interest in

rimfire cartridges, with two new rimfires introduced, both in .17 caliber

(4.5 mm).

Rocket Ball From Wikipedia

The Rocket Ball was one of the earliest forms of

metallic cartridge for firearms, containing bullet and powder in a single,

metal cased unit.

| Construction

The Rocket Ball, patented in 1848 by Walter Hunt, consisted

of a lead bullet with a deep hollow in the rear, running a majority of

the length of the cartridge. The hollow, like that of the Minie ball, served

to seal the bullet into the bore, but Rocket Ball put the cavity to further

use. By packaging the deep cavity with powder, and sealing it with a cap

with a small hole in the rear for ignition, the Rocket Ball replaced the

earlier paper cartridge with a durable package capable of being fed from

a magazine. The cap was blown out of the bore upon firing, leaving no cartridge

case to be ejected, making the Rocket Ball a form of caseless ammunition.

The Rocket Ball was used in the earliest magazine fed lever action guns,

allowing the first practical repeating, single chamber firearms.

Use

The Jennings rifle, top, shows the hammer and nipple needed

for the Rocket Ball's external percussion cap. The later Volcanic rifle,

bottom, used the internally primed Volcanic cartridge

The Jennings rifle, top, shows the hammer and nipple

needed for the Rocket Ball's external percussion cap. The later Volcanic

rifle, bottom, used the internally primed Volcanic cartridge

While the Rocket Ball provided the means of making practical

repeating firearms, it was not an ideal solution. The limited volume in

the base of the bullet severely limited the amount of powder that could

be used, and thus limited the potential velocity and range of the cartridge.

Despite these limitations, the Rocket Ball was used in a number of attempts

at making a commercially successful firearm, culminating in the Volcanic

Repeating Arms Company. The Volcanic cartridge went one step further, adding

a primer to the cap of the Rocket Ball, making the ammunition completely

self contained. |

Drawing from US patent 5,701, for

Walter Hunt's Rocket Ball metallic cartridge |

|

| Reloading Bottleneck and Long Tapered Rifle

Cases by Cliff Hanger

Those of us that reload bottleneck

and long tapered rifle cases have at some time had rounds that would not

chamber correctly. We use the right die set but yet the rounds lack about

1/8" of entering the chamber completely. In rifles usually the levering

advantage will force the round home. But in pistols the round rim sticks

up out of the cylinder and requires a lot of force that may not seat the

round full. Now the pistol cylinder will not rotate.

What's going on?

Well, my opinion is that during

the reloading process the crimping process is the culprit. When the die

rolls over the brass in to the crimp groove, the brass is being swaged

from one diameter to a smaller diameter. This process causes the brass

to form a slight bulge about 1/16" to 1/8" below the neck of the case.

Now you say , "I don't have problems with my straight case rounds." Actually

you do. But the crimp die for straight cases have an advantage that the

tapered dies do not. As the brass is rolled in to the crimp groove, the

brass does bulge but as the case is straight the die hold the brass to

it's maximum diameter. Also when pulling the round out of the die it full

length sizes the round at maximum spec. diameter. So you really don't see

or have the bulged case. (Yes I know, we can crimp even if there is no

groove in all lead bullets. The problem is the same.)

Bottleneck or tapered cases also

produce this bulge when the brass is crimped in to the groove. But when

the round is pulled out of the die the die side walls move away from the

brass as the die gets bigger for the large bases of the cases. This process

does not resize the sides of the case leaving this slight bulge.

You may not see this slight bulge.

But if you measure the case about 1/4" down from neck then move the calipers

up they will open up slightly as they go over this bulge. It is enough

something to stop the rounds from chambering correctly. I have seen from

no bulge at all to as much as .004"

If you load a lot of these bottleneck

cases and long tapered cases for cas, you probably don't check the overall

length and trim those found to be a little long. I know I don't. I only

check for overall loaded length.

So what can we do if you have this

problem? I'll tell you what I do. And No I do not use a "Factory Crimp

Die". I use standard reloading dies. But not as you might use them.

So let's see if I can get through

this one step at a time:

1. Toss the brass to be loaded in

to the tumbler. I have a mechanical 4 hour windup timer. I paid $12.00

for it at a electrical wholesale house. It runs 3 to 3.5 hours a day. 4

days a week. Some times twice a day. The cheap electric ones from the hardware

store just don't hold up under daily use. The plastic turn off/turn on

pieces break.

| 2. I set my press up

for the caliber to be done. I have an extra tool head that I keep handy

on the shelf. In this tool head I put a sizing die with NO

decapping pin. I run it all the way down

to the shell plate pre die instructions. Case Lube. I use Honaday

One Shot spray lube. Doesn't take much and you don't have to get all the

way around every case. I place the brass about 200 at a time in a 3 gallon

bucket and give a quick shot. Then I shack the bucket and give one more

spray. I let them dry before putting them on the press. I now resize all

the brass to spec. |

|

3. Once this is done, I toss the brass

back in to the tumbler for about 1 hour. This gets the case lube off and

makes shinny cases.

| 4. With a full toolhead

on the press, I start the normal reloading process.

However, I do not want to stick

any of these cases in the sizing die which without lube will happen. So

in station one, I use a Universal Decapping die instead of a sizing die.

It will accept rounds up to 45-70 without touching the case outside walls.

It only pushed the spent primers out. The rest of the loading process is

normal. |

|

5. Powder is measured and dropped using

your standard methods.

| 6. Next you place your bullet of

choice on the case and seat it.

If you are using Dillion dies, you

adjust the seating of the bullet per their instructions.

If you are using any of the many

Bullet Seating/Crimping dies you adjust them per their instructions.

I use Lee dies because I like them.

Also by using the combination die, it frees up one station in the toolhead.

The reason for this will be explained later. |

|

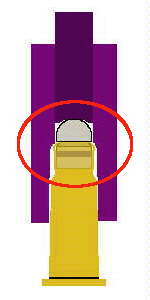

| 7. Which ever die set you use, the crimping procedure

is about the same. The round is run up in to the die and at the top of

the stroke the brass is swaged in against the bullet and the top of the

case is rolled in to the crimp groove.

This is where the bulge in the case comes from. Noted

on drawing.

When the case is withdrawn from the crimping die the die

sides move away quickly leaving the bulge.

At this point you have a loaded

round but most likely have this slight bulge issue. If your guns will take

these rounds then you're done. If not, then we go on.

|

|

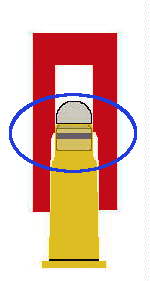

Now for the magic! I have one more

step to do.

| 8. My press allows me

to put one more die in the toolhead after the crimping station because

I use the Lee Seating/Crimping die. They do the job and are cheaper then

other dies. I use Dillion presses. But the press is just a personal preference.

What I do is put a sizing die in

the last station. Remember I have NO decapping pin in the die as I used

it is step 2. I place it in the last station in the toolhead but I do not

run it down. I raise the loaded round up to the top of the press stroke.

I then screw the resizing die down as tight as I can get it by hand. I

lower the round a little and then turn the sizing die 1/2 turn. Run

the round up in to the die. I remove the round and inspect it with my calipers.

I am looking for the bulge. If it is still there, I return the round to

the press and turn the sizing die down 1/4 turn and do the process again.

There will be a point where the bulge will be flattened out and in line

with the rest of the case on the side of the bullet but not touch the rest

of the case. If you screw the die in too far you will be resizing the bullet

in the case. We don't want that. We want just enough to remove the bulge

at the neck of the case.

.

If your press does not have enough holes in the tool

head to include the last step. Don't worry. Just like the first sizing

step, just put the toolhead with just the sizing die in it back on the

press. Sure you will have to run the rounds through the press a third time.

But the benefits at the range of not worrying if your rounds will chamber

is worth every minute you spend at the press. Oh! One more thing. During

the First sizing step and if you have to run the rounds through the press

a third time, make it easy on yourself. You're not pushing the primers

out so put the sizing die in the easiest station to put round in. I use

station 4 on Dillion 650s. When I have to put loaded rounds in the press

this is the easiest station to do that. It is where you usually place the

bullets on the case.

.

Now go out and shoot smaller groups without fighting

the Bulge! |

Finished Round

with NO bulge

|

|