| Dodge City, Kansas from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

EARLY HISTORY

The early history of Dodge city is as colorful as any

town in the American West.

ORIGINS

The first settlement in the area that became Dodge City

was Fort Mann. Built by civilians in 1847, Fort Mann was intended to provide

protection for travelers on the Santa Fe Trail. Fort Mann collapsed in

1848 after an Indian attack. In 1850, the U.S. Army arrived to provide

protection in the region and constructed Fort Atkinson on the old Fort

Mann site. The army abandoned Fort Atkinson in 1853. Military forces on

the Santa Fe Trail were reestablished further north and east at Fort Larned

in 1859, but the area around what would become Dodge City remained vacant

until after the Civil War. In 1865, as the Indian Wars in the West began

heating up, the army constructed Fort Dodge to assist Fort Larned in providing

protection on the Santa Fe Trail. Fort Dodge remained in operation until

1882.

The town of Dodge City can trace its origins to 1871 when

rancher Henry J. Sitler built a sod house west of Fort Dodge to oversee

his cattle operations in the region. Conveniently located near the Santa

Fe Trail and Arkansas River, Sitler's house quickly became a stopping point

for travelers. With the Santa Fe Railroad rapidly approaching from the

east, others saw the commercial potential of the region. In 1872, just

five miles west of Fort Dodge, settlers platted out and founded the town

of Dodge City. George M. Hoover established the first bar in a tent to

service thirsty soldiers from Fort Dodge. The railroad arrived in September

to find a town ready and waiting for business. The early settlers in Dodge

City traded in buffalo bones and hides and provided a civilian community

for Fort Dodge. However, with the arrival of the railroad, Dodge City soon

became involved in the cattle trade.

Cattle trade

The idea of driving Texas longhorn cattle from Texas

to railheads in Kansas originated in the late 1850s but was cut short by

the Civil War. In 1866, the first Texas cattle started arriving in Baxter

Springs in southeastern Kansas by way of the Shawnee Trail. However, Texas

longhorn cattle carried a tick that spread splenic fever among other breeds

of cattle. Known locally as Texas Fever, alarmed Kansas farmers persuaded

the Kansas State Legislature to establish a quarantine line in central

Kansas. The quarantine prohibited Texas longhorns from the heavily settled,

eastern portion of the state.

With the cattle trade forced west, Texas longhorns began

moving north along the Chisholm Trail. In 1867, the main Cow Town was Abilene,

Kansas. Profits were high, and other towns quickly joined in the cattle

boom. Newton in 1871; Ellsworth in 1872; and Wichita in 1872. However,

in 1876 the Kansas State Legislature responded to pressure from farmers

settling in central Kansas and once again shifted the quarantine line westward,

which essentially eliminated Abilene and the other Cow Towns from the cattle

trade. With no place else to go, Dodge City suddenly became Queen of the

Cow Towns.

A new route, known as the Great Western Cattle Trail,

or Western Trail, branched off from the Chisholm Trail to lead cattle into

Dodge City. Dodge City became a boomtown, with thousands of cattle passing

annually through its stockyards. The peak years of the cattle trade in

Dodge City were from 1883 to 1884, and during that time the town grew tremendously.

In 1880, Dodge City got a new competitor for the cattle trade from the

border town of Caldwell. For a few years the competition between the towns

was fierce, but there were enough cattle for both towns to prosper. Nevertheless,

it was Dodge City that became famous, and rightly so because no town could

match Dodge City's reputation as a true frontier settlement of the Old

West. Dodge City had more famous (and infamous) gunfighters working at

one time or another than any other town in the West, many of whom participated

in the Dodge City War of 1883. It also boasted the usual array of saloons,

gambling halls, and brothels established to separate a lonely cowboy from

his hard-earned cash, including the famous Long Branch Saloon and China

Doll brothel. For a time in 1884, Dodge City even had a bullfighting ring

where Mexican bullfighters imported from Mexico would put on a show with

specially chosen longhorn bulls.

As more agricultural settlers moved into western Kansas,

pressure on the Kansas State Legislature to do something about splenic

fever increased. Consequently, in 1885 the quarantine line was extended

across the state and the Western Trail was all but shut down. By 1886,

the cowboys, saloon keepers, gamblers, and brothel owners moved west to

greener pastures, and Dodge City became a sleepy little town much like

other communities in western Kansas.

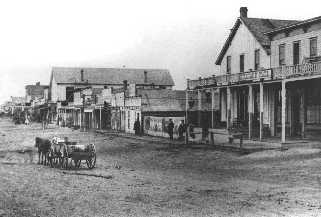

Front Street, Dodge City, Kansas 1880 |

|

| Conestoga Wagon

The Conestoga wagon is a heavy, broad-wheeled covered

freight carrier used extensively during the United States Westward Expansion

in the late 1700s and 1800s. It was large enough to transport loads up

to 8 short tons (7 metric tons), and was drawn by 4 to 8 mules or 4 to

6 oxen.

History

The first Conestoga wagons appeared in Pennsylvania around

1725 and are thought to have been introduced by Mennonite German settlers

in that area, and its name came from the Conestoga Valley in that region.

In colonial times the conestoga wagon was popular for migration southward

through the Great Appalachian Valley along the Great Wagon Road. After

the American Revolution it was used to open up commerce to Pittsburgh and

Ohio. In 1820 rates charged were roughly one dollar per 100 pounds per

100 miles, with speeds about 15 miles (25 km) per day. The Conestoga, often

in long wagon trains, was the primary overland freight vehicle over the

Appalachians until the development of the railroad. Subsequently it played

a role in Western settlement, especially on the Santa Fe Trail, where ox

and mule teams could pull its vast cargo with fewer water stops. The Conestoga

wagon is a significant historical item that was used extensively during

the United States’ westward expansion in the late 1700s and 1800s. If it

had not been for the Conestoga wagons, the Westward Expansion would have

been greatly slowed for lack of transportation.

The Conestoga wagon was cleverly built. Its floor curved

upward to prevent the contents from tipping and shifting. Also for protection

against bad weather, stretched across the wagon was a tough, white canvas

cover. It was 16.5 feet in length and 4.5 feet in width.

Prairie schooners

The term prairie schooner is often used to replace Conestoga

wagon. These commercial wagons were much too huge, heavy, and hard to handle

to be used by families emigrating to Oregon, Utah, California,or Virginia

in the nineteenth century. Thus, the westward-bound emigrants’ conveyance

of choice was the smaller, lighter, farm-type wagon which could be drawn

by teams of fewer animals. Crammed inside these small wagons were supplies

for the 2,000-mile journey ahead, a few precious items from back East,

and tools to help establish their future homes in the West.

The emigrants themselves never called their wagons Conestoga

or prairie schooners. Nineteenth-century diaries and reminiscences reveal

that westering emigrants during the time of their journeys — the 1840s,

1850s, and 1860s — generally referred to their vehicles simply as "wagons"

or "waggons." Travelers crossing the prairie gazed at the lines of white-topped

wagons rumbling across the dying grass and described the wagons as "ships

upon the ocean," or ships on "rolling waves of green from horizon to horizon,"

or as resembling "dim sails crossing a rolling sea." But they never called

their wagons “prairie schooners.”

English adventurer Fred Ebb penned the almost magic words

in his journal, in 1860 during an overland trip to Utah, when he wrote

the wagon “is literally a "prairie ship: its body is often used as a ferry.”

A few emigrant diaries make references to "prairie schooners," but only

when describing the large, freight-bearing Conestoga wagons that accompanied

some military expeditions or commercial ventures. It was not until the

pioneers began penning (and romanticizing) their reminiscences during the

1870s and later — long after their migration to the West — that they began

calling their own simple wagons "prairie schooners." Even then, some authors

near the end of the century felt the term was unusual enough to feel it

necessary to explain that an emigrant's wagon "came to be known in those

days as a prairie schooner." |

A covered wagon replica at the

High Desert Museum, Bend, Oregon

.

.

A late example of a covered wagon in actual use

Idaho, 1940 |

|

| Studebaker From Wikipedia

Studebaker Corporation, or simply Studebaker, was a United

States wagon and automobile manufacturer based in South Bend, Indiana.

Originally, the company was a producer of industrial mining wagons, founded

in 1852 and incorporated in 1868 under the name of the Studebaker Brothers

Manufacturing Company. While Studebaker entered the automotive business

in 1902 with electric vehicles and 1904 with gasoline vehicles, it partnered

with other builders of gasoline-powered vehicles until 1911. In 1913, Studebaker

introduced the first gasoline-powered automobiles under its own “Studebaker”

brand name. Acquired in 1954 by Packard Motors Company of Detroit, Michigan,

Studebaker was a division of the Studebaker Packard Corporation from 1957

to 1962. In 1962, it reverted to its previous name, the Studebaker Corporation.

While the company left the automobile business in 1966, Studebaker survived

as an independent closed investment firm until 1967 when it merged with

Worthington to become Studebaker-Worthington Corp.

History

Henry Studebaker was a farmer, blacksmith, and wagon-maker

who lived near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in the early 19th century. By 1860,

he had moved to Ashland, Ohio and taught his five sons to make wagons.

They all went into that business as it grew westward with the country.

Clement and Henry Studebaker Jr. became blacksmiths and foundrymen in South

Bend. They first made metal parts for freight wagons and later expanded

into the manufacture of complete wagons. John made wheelbarrows in Placerville,

California, and Peter made wagons in Saint Joseph. The site of John's business

is Chinas Historic Landmark #142. The first major expansion in their business

came from their being in the right place to meet the needs of the California

Gold Rush in 1849.

When the gold rush settled down, John returned to Indiana

and bought out Henry's share of the business. They brought in their youngest

brother, Jacob, in 1852. Expansion continued to support westward migration,

but the next major decrease came from supplying wagons for the Union Army

in the Civil War. After the war, they reviewed what they had accomplished

and set a direction for the company.

They reorganized into the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing

Company in 1878, built around the motto of "Always give more than you promise."

By this time the railroad and steamship companies had become the big freight

movers in the east. So they set their sights on supplying farmers and others

with the means to move themselves and their goods. Peter's business became

a branch operation.

During the height of westward migration and wagon train

pioneering, half of the wagons were Studebakers. They made about a quarter

of them, and manufactured the metal fittings to sell to other builders

in Missouri for another quarter century.

Studebaker Automobiles 1897-1966

Studebaker experimented with powered vehicles as early

as 1897, choosing electric over gasoline engines. While it attempted to

manufacture its own electric vehicles from 1902 to 1912, the company entered

into a distribution agreement with two manufacturers of gasoline powered

vehicles: Garford of Elyria, Ohio, and the Everett-Metzger-Flanders (E-M-F)

Company of Detroit.

Under the agreement with Studebaker, Garford would receive

completed chassis and drivetrains from Ohio and then mate them with Studebaker

built bodies, which were sold under the Studebaker-Garford brand name and

at a premium price. Eventually, even the Garford built engines began to

carry the Studebaker name. However, Garford also built a limited number

of cars under its own name, and by 1907 attempted to increase production

at the expense of Studebaker. Once the Studebakers discovered what was

going on with their partner, John Moehler Studebaker enforced a primacy

clause, forcing Garford back onto the scheduled production quotas. The

decision to drop the Garford was made and the final product rolled off

the assembly line by 1911, leaving Garford to try it alone until it was

acquired by John North Willys in 1913.

Studebaker's marketing agreement with E-M-F was a different

relationship, one that John Studebaker had hoped would give Studebaker

a quality product without the entanglements found in the Garford relationship.

Unfortunately, this was not to be the case.

Under the terms of the agreement, E-M-F would manufacture

vehicles and the Studebakers would distribute them through their wagon

dealers. Problems with E-M-F made the cars unreliable, leading the public

to say that E-M-F stood for "Every Morning Fix-it."[citation needed] Compounding

the problems was the internal fighting between E-M-F's principal partners,

Mr. Everett, Mr. Flanders and Mr. Metzger. Eventually, two-thirds of the

trio left, leaving the bombastic Mr. Metzger to run the operation on his

own. J.M. Studebaker, unhappy with E-M-F's poor quality, gained control

of the assets and plant facilities in 1910. To remedy the damage done by

E-M-F, Studebaker paid mechanics to visit each unsatisfied owner and replace

the defective parts in their vehicles at a cost to the company of US$1

million.

Studebaker also began putting its name on new automobiles

produced at the former E-M-F facilities, both as an assurance that the

vehicles were well-built, and as its commitment to making automobile production

and sales a success. In 1911, the company reorganized as the Studebaker

Corporation.

In addition to cars, Studebaker added a truck line, which

in time, replaced the horse drawn wagon business started in 1852. In 1926,

Studebaker became the first automobile manufacturer in the United States

to open a controlled outdoor proving ground; in 1937 the company planted

5,000 pine trees in a pattern that when viewed from the air spelled "STUDEBAKER."

From the 1920s to the 1960s, the South Bend company originated

many style and engineering milestones, including the classic 1929-1932

Studebaker President and the 1939 Studebaker Champion. During World War

II, Studebaker produced the Studebaker US6 truck in great quantity and

the unique M29 Weasel cargo and personnel carrier. After cessation of hostilities,

Studebaker returned to building automobiles that appealed to average Americans

and their need for transportation and mobility.

However, ballooning labor costs (the company had never

had an official United Auto Workers (UAW) strike and Studebaker workers

and retirees were among the highest paid in the industry), quality control

issues, and the new car sales war between Ford and General Motors in the

early 1950s wreaked havoc on Studebaker's balance sheet. Professional financial

managers stressed short term earnings rather than long term vision. There

was enough momentum to keep going for another ten years, but stiff competition

and price cutting by the Big Three doomed the enterprise. There was also

a labor strike at the South Bend plant in 1962.

Merger with Packard

Hoping to stem the tide of losses and bolster its market

position, Studebaker allowed itself to be acquired by Packard Motor Car

Company of Detroit; the merged entity was called the Studebaker-Packard

Corporation. Studebaker's cash position was far worse than it led Packard

to believe and, in 1956, the nearly bankrupt auto-maker brought in a management

team from aircraft maker Curtiss-Wright to help get it back on its feet.

At the behest of C-W's president, Roy T. Hurley, the company became the

American importer for Mercedes-Benz, Auto Union, and DKW automobiles and

many Studebaker dealers sold those brands as well. In 1958, the Packard

name was discontinued, although the company continued to bear the Studebaker-Packard

name through 1962.

With an abundance of tax credits in hand from the years

of financial losses, at the insistence of the company's banks and some

members of the board of directors, Studebaker-Packard began diversifying

away from automobiles in the late 1950s. While this was good for the corporate

bottom line, it virtually guaranteed there would be little spending on

Studebaker's mainstay products, its automobiles.

The automobiles that came after the diversification process

began, including the ingeniously-designed compact Lark (1959) and even

the Avanti sports car (1963), were based on old chassis and engine designs.

The Lark, in particular, was based on existing parts to the degree that

it even utilized the central body section of the company's 1953 cars, but

was a clever enough design to be quite popular in its first year, selling

over 150,000 units and delivering an unexpected $28 million profit to the

automaker.

Hamilton, Ontario

On August 18, 1948, surrounded by more than 400 employees

and a battery of reporters, the first vehicle, a blue Champion four-door

sedan, rolled off of the Studebaker assembly line in Hamilton, Ontario,

Canada. The company was located in the former Otis-Fenson military weapons

factory off Burlington Street on Victoria Avenue North, which was built

in 1941. The Indiana-based Studebaker Corporation was looking for a Canadian

site and settled on Hamilton because of its steel industry. The company

was known for making automotive innovations and building solid, distinctive

cars. 1950 was its best year, but the descent was quick. By 1954, Studebaker

was in the red and merging with Packard, another troubled car manufacturer.

In 1963, the company moved its entire car operations to Hamilton. The Canadian

car side had always been a money-maker and Studebaker was looking to curtail

disastrous losses. That took the plant from a single to second shift -

48 to 96 cars daily.

The last car to roll off the line was a turquoise Lark

cruiser on March 16, 1966. Studebaker officially announced the shutdown

of its last car factory on March 4. It was terrible news for the 700 workers

who had formed a true family at the company, known for its employee parties

and day trips. It was a huge blow to the city, too. Studebaker was Hamilton's

10th largest employer at the time.

Non-Auto Businesses

Studebaker was involved in other areas of manufacture

besides automobiles. The Franklin Appliance Company manufactured Home Appliances

such as Refrigerators and such, until its sale to White Consolidated Industries.

Studebaker also owned and manufactured STP, Gravely Tractor,

Onan Electric Generators, and Clarke Floor Machine.

Studebaker

John Studebaker arrived in Placerville, CA. on August

31, 1853 at nineteen years old. He left for home with his fortune of $8000

in 1858 at the age of 25.

Some think that John had left part of his fortune behind.

Wheelbarrow

Johnny's Lost Gold |

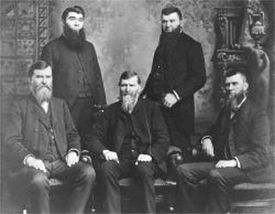

Five Studebaker Brothers

top left ... Peter and Jacob

bottom left ... Clement, Henry and John |

You are probably wondering what this has to do

with anything. Well the wheel barrows built by John in the California gold

fields were called Studebakers and the wagons built by the Studebaker brothers

were called Conestogas Wagons.

|